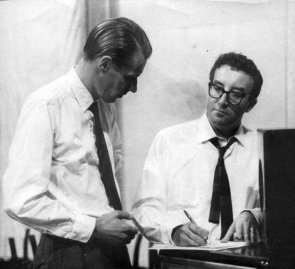

George Martin is

inarguably the most successful music producer of all-time.

If

there’s anyone who can legitimately lay claim to the mantle of “Fifth”

Beatle, it’s George Martin. Martin’s unparalleled production expertise

coupled with his profound talents as a musician, arranger and conductor

helped catapult The Fab Four to unprecedented waves of worldwide

success.

Born

in London in 1926, Martin has been an integral force in the musical

scene for almost fifty years. Classically trained at The Guildhall

School of Music, Martin parlayed his education with a job as assistant

to Oscar Preuss, EMI Parlophone record chief. After Preuss retired in

1955, Martin was elevated to head of Parlophone where he worked with

such disparate acts as Peter Sellers, Shirley Bassey, Stan Getz, Sir

Malcolm Sargent and Sophia Loren.

Prior to his involvement with The Beatles, Martin had a rich and diverse

career, working in the fields of classical, comedy, jazz and light pop.

His exemplary work with the legendary British comedy troupe “The Goons”

further cemented Martin’s reputation – impressing John Lennon

in particular.

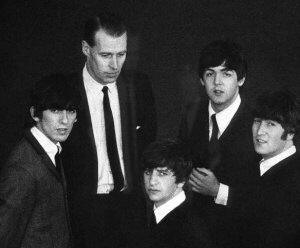

But

the course of George Martin’s life inexorably changed – as it did for

four lads from Liverpool – on June 6, 1962. This was the fateful date

Martin first met the Beatles at a recording audition for Parlophone

Records held at London’s Abbey Road Studios. Impressed more with the

group’s cheeky charm and charisma than their as yet latent musical

talents, (George Harrison even criticized the producer’s tie!), Martin

signed the group to Parlophone, in the process making undoubtedly the

smartest A&R move in recording history.

Yet

while it’s his long-standing connection with the Beatles that is most

widely known, Martin is also responsible for working/and or producing a

Besides his

historic work with The Beatles, he has produced sessions for a dazzling

array of disparate artists including Jeff Beck, Judy Garland, Pete

Townshend, Elton John, America, jazz great Stan Getz, Aerosmith, comedy

legend Peter Sellers, Bee Gees, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Cheap Trick, Jimmy

Webb, Badfinger, Ultravox, Gerry & The Pacemakers, UFO, Billy J.

Kramer, Procol Harum’s Gary Brooker, Cilla Black and many more.

Ken

Sharp caught up with Sir George Martin for a career spanning chat.

Tell

us about your musical beginnings at Guildhall School of Music and how

that background influenced your later work.

Well, I was very similar to both John and Paul in a way where I wasn’t

taught music to begin with. I just grew up feeling music and naturally

making music. I can’t remember a time where I wasn’t making music on the

piano. I was running a band by the time I was fifteen.

What

was the name of the band?

(Laughs)

Very corny but I thought it was fantastic. The first one was a four

piece and then it became a five piece. When it was a four piece I called

it “The Four Tune Tellers” (laughs again). Then it became “George

Martin and the Four Tune Tellers”. Very clever. I had TT’s on the stands

in front. We made quite a little bit of money as well. Then the war

intervened and by the time I was seventeen I was in the Fleet Air Arm

which is part of the Royal Navy. We flew off carriers and we were fliers

in the Navy. That was the tail end of the war. I was four years in the

service; I was twenty one when I came out. Having managed to evade

Japan, I was all right. And I had no career. A professor of music who

befriended me, he’s received from me during the war various compositions

that I’d painfully put together. I went to see him and said, “you must

take up music.” I said, “How can I? I’m not educated. I’ve never had any

training?” He said, “Well get taught. I’ll arrange it for you.” He

arranged an audition for me to play some of my work to the principal of

the Guildhall School of Music and Drama – which is a college in London.

He said “we’ll take you on as a composition student.” I got a government

grant for three years to study. I started composition, conducting and

orchestration and I took up the oboe. I took up the oboe so I could make

a living playing some instrument. You can’t make a living playing the

piano. I just played piano naturally. I wasn’t taught. I didn’t take

piano as a subject because I didn’t see any future in it, I didn’t rate

myself as being a great pianist. I could never see myself making a

living at it. I wanted to be a film writer. So that’s what happened. I

was trained and I came out and I would work playing the oboe in

different orchestras in the evenings and sometimes afternoons in the

park, that kind of thing. I was a jobbing oboe player.

Do

you still play?

Do

you still play?

No

(laughs). I don’t think I could now. I took a job during the day

to make some extra money. That was in the music department at the BBC.

Then out of the blue I got a letter from someone asking me to go for an

interview at a place called Abbey Road. So I cycled along there and the

guy said, “I’m looking for someone to help me make some classical

recordings and I gather you can do this.” Because I was a woodwind

player and educated by now, I got the job of producing the classical

baroque recordings of the Parlophone label. And I got hooked. Gradually

this guy who was running the label gave me more and more work to do. I

started doing jazz records, orchestral, pop of the period. It wasn’t

rock. Over a period of five years I worked as his assistant gradually

doing more and more. By the time the five years was up I was virtually

doing everything. Five years later in 1955, he retired. He was sixty

five years old and he left. I thought somebody was going to be brought

in over me because I was in my twenties still. But to my astonishment I

was given the job of running the label. I was the youngest person ever

to be given that job.

Prior to your work with The Beatles, you worked in many different

musical idioms. How did that impact your production skills? It seemed

you were very willing to be experimental in your work with The Beatles.

Oh

absolutely. But I always was experimental even before The Beatles came

along. One of the records I made was an electronic record called “Ray

Cathode” which was collaborating with the BBC radiophonics people. I

made a lot of what I call “sound pictures” with actors and comedians –

because it was fun to do. I’m a person who gets bored quite easily and I

don’t like doing the same thing over and over again. Once I was running

the label I didn’t earn much money, but I did have freedom to do what I

wanted to do.

Discuss your approach toward string arrangements. Your work on Beatle

songs like “Strawberry Fields Forever”, “Eleanor Rigby” and “Glass

Onion” is extraordinary.

The

writing of the parts is me and the requirements are them. It varied

between John and Paul. Paul was generally quite articulate with what he

wanted. Mostly we would sit down at the piano together and play it

through and work out how it would sound. Paul still doesn’t know how to

orchestrate but he knew what he wanted and would give me ideas and I

would say “you can’t do that” or “you can do this.” We’d talk about it,

talk it through. John would never take that kind of attention. John was

less articulate and much more full of imagery. He would have ideas which

were difficult to express. It was quite difficult for me to interpret.

One of the problems was getting inside his brain to find what he really

wanted. Quite often he would say, “you know me, you know what I want.:

In the case of “I Am The Walrus,” when I first heard that he just stood

in front of me with a guitar and sang it through. But it was weird. I

said to him, “What the hell am I going to do with this, John?” He said,

“I’d like for you to do a score and use some brass and some strings and

some weird noises. You know the kind of thing I want.” I didn’t but I

just went away and did that.

What

orchestral arrangement that you did for The Beatles of which you’re most

proud? “Strawberry Fields Forever” is a wild score.

What

orchestral arrangement that you did for The Beatles of which you’re most

proud? “Strawberry Fields Forever” is a wild score.

The

Beatles wanted something unusual. Although at the core of it is

orchestration that I liked to do. I liked to have clean orchestration.

I’ve got various theories about orchestration. I don’t think the human

brain can take it too many notes at once. For example, when you’re

listening to a fugue of Bach or someone and you hear the first statement

and the second one joins it, you can catch hold of that all right and

then the third one comes in and it starts to get more complicated. Any

more than that and it then it becomes a jumble of sound. You can’t

really sort out what is what.

Tell

us about the time you tried to turn John Lennon onto a piece of

classical music.

He

went back to my flat one night. We had dinner and were rapping away. We

were talking about different kinds of music. I wanted to play him one of

my favorite pieces of classical music. It was the “Deathless and Fairy

Suite Number Two” by Ravel, which is a gorgeous piece of music. It lasts

about nine minutes and he sat through it patiently. I mean it’s one of

the best examples of orchestration you can get because it’s a swelling

of sound that is just breathtaking. He listened very patiently and said,

“Yeah, it’s great. The trouble is by the time you get to the end of the

tune you can’t remember what the beginning’s like”. I realized it was

too stretched out for him to appreciate in one go. He couldn’t

assimilate it. He was so used to little soundbites. A lot of people are

nowadays. It’s the curse of advertising and television that we are now

tuned to little jingles that we can connect and recognize right away. We

can’t listen to anything longer than that, so consequently the way

people write sometimes is to connect together a lot of little jingles –

which is not maybe the best way of doing things.

When

you met up with John in the 70’s he would tell you if he had the chance

he would re-record every Beatles song. Could you understand where he was

coming from?

It’s

a funny thing, when John said this to me originally was when we were

spending an evening together. It shook me to the core when we were

talking about old things and he said, “I’d love to do everything again.”

To me that was just a horror. I said, “John, you can’t really mean it.

Even ‘Strawberry Fields?’” He said, “Especially ‘Strawberry Fields!’” I

thought, oh shit, all the effort that went into that. We worked very

hard on that trying to capture something that was nebulous. But I

realized that John was a dreamer. In John’s mind everything was so

beautiful and much better than it was in real life. He was never a

person of nuts and bolts. The bitter truth is music is nuts and bolts;

you’ve got to bring it down to horse hair going over a bit of wood,

people blowing into brass tubes. You’ve got to get down to

practicalities.

In

the Sixties, did any of the other major British bands – like The Who,

The Kinks, The Small Faces and The Rolling Stones – attempt to have you

produce them?

In

the Sixties, did any of the other major British bands – like The Who,

The Kinks, The Small Faces and The Rolling Stones – attempt to have you

produce them?

They

didn’t approach me, mainly because I was so damn busy. I really couldn’t

have worked any harder than I did. All of the people from Brian’s

(Epstein) stable came along; I was just about able to cope with those

and very little more. I had a tremendous roster of artists.

You

did work later in your career with another major Sixties band, The Bee

Gees. How would you characterize their talents?

Terrific songwriters. I remember going to meet with them in The Bahamas

when we were talking about doing the Sgt. Pepper film and they

played me the tracks that they just recorded for a new film that nobody

had ever heard about called Saturday Night Fever. I couldn’t

quite connect what I was hearing with the guys that I knew because it

was so hip. I was looking at Barry and Maurice and Robin and I was

saying it was a great dance sound. It could have been Motown, it was so

good. I asked, “Have you done this? It’s fantastic. You’ve got big hits

here.” I was enormously impressed. What was good about them was they

weren’t just writing good songs but they were writing good production

ideas into the songs the way that they were putting it together – and

the guitar work. Barry is very talented and the others also contribute

quite a bit too.

And

in the early 70’s you produced Jeff Beck’s now classic album

Blow

By Blow and you had him cover “A Day in the Life.”

Jeff

and I had been mates for a long time although we hadn’t worked together

for a long time. But we’ve talked about working together and never got

around to it. And Jeff came to see me when I was working on the

Anthology at Abbey Road. It so happens that the day he came in Paul

was already there listening to stuff that I’d selected for him to hear.

It was then, in front of Paul, where we talked about him doing a track

for the album. Jeff said to me, “Can I choose the track?” I said, “Sure,

if you want to.” He picked “A Day in the Life.”

He

covered The Beatles’ “She’s A Woman” on the

Blow

By Blow album.

That’s right. It was good track, wasn’t it? He used “the bag” on that.

Anyhow, you could have knocked me sideways when he chose to do “A Day in

the Life.” I thought he would have chosen to do something like “Yer

Blues.” When he did it, I was very pleased to hear what he he’d done.

We also spoke to a

few luminaries in attendance at Grammy Foundation Starry Night Benefit

Honoring Sir George Martin who shared their thoughts on his importance

in music.

Lamont Dozier

(legendary songwriter of Motown’s hitmaking writing team,

Holland-Dozier-Holland):

George Martin’s

production work with The Beatles definitely had a big influence on our

production work. The tracks that he did like “The Long & Winding Road”,

they were so mind blowing and also new in their approach. George Martin

and The Beatles together were innovators and they brought to the table

so many new things and new approaches to music that made us work harder.

Those Beatle records were daring to take a chance and jump into the

fire. As writers and producers they just jumped out there and did it.

They didn’t follow the crowd, they had the crowd follow them.

Jeff Lynne

As a member of ELO,

The Move and The Idle Race and an established producer in his own right,

Jeff Lynne’s musical style is profoundly inspired by The Beatles. Here’s

his take on George Martin’s legacy.

I think George

Martin’s approach as a producer was very classy. The decisions he made

in the studio, the way he blended instruments together, the way he

pioneered bouncing tracks across and back and forth from machine to

machine. He made records you couldn’t make in those days because you

didn’t have enough facilities. Now everyone has a million tracks to work

on but I’m sure they’ll never come up with anything as good as he did on

four-track.

George has always

been a big inspiration to me just listening to the records he made –

like I said, just the class that he brings to it. He’s a wonderful

musician as well. I think that the two together is what makes him what

he is. He’s above the rest of everybody.

Yoko Ono

George Martin is

somebody that meant so much to the Beatles and the Beatles family.

That’s why I flew in from New York to be here for this event. As a

producer, he had a sense of that period and the time of the world as

well as the music. He had this feeling what would work well at the

time.

Leiber & Stoller

What Lennon and

McCartney meant to the Sixties, the esteemed songwriting team of Jerry

Leiber and Mike Stoller meant to the pulse of the 50’s music scene.

Jerry Leiber:

George Martin initiated a whole world of sound and music. Even

though there were singers and performers, George Martin was the mind

that pulled it all together and made it more interesting than pop music

ever was.

Mike Stoller:

I feel the same way. I feel that he created out of working with a group

of extremely talented people. He created something that was beyond a

group of talented people because he brought his own musical genius to

that and created the Beatles sound.

Tom Jones

Singer Tom Jones

worked with George Martin in the studio on “Come Sweep My Chimbley,” a

track earmarked for the

Under Milkwood

project.

It was a Dylan

Thomas poem but then he did the music. It was good. We did it for the

Prince’s Trust and recorded it in George’s studio in London. That was

the first time I worked with him. I actually recorded it with George in

L.A. But we did the musical for the Prince’s Trust. As a producer he’s

so musical. He’s a great musician and he knows a lot about music and

he’s got a great sense of humor as well; he made a lot of comedy records

(The Goons, Peter Sellers) before he became famous working with The

Beatles. He’s such an easy person to get along with. As soon as I

started working with him I was in tune with him.

Features

Return to the features page