Copyright ©2006 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

September 3, 2006.

Allen Coulter has been

behind the scenes on some of the most revolutionary TV shows of the last

decade. He directed multiple episodes of such big screen worthy series as

The X-Files, The Sopranos, Sex and the City and Six Feet Under.

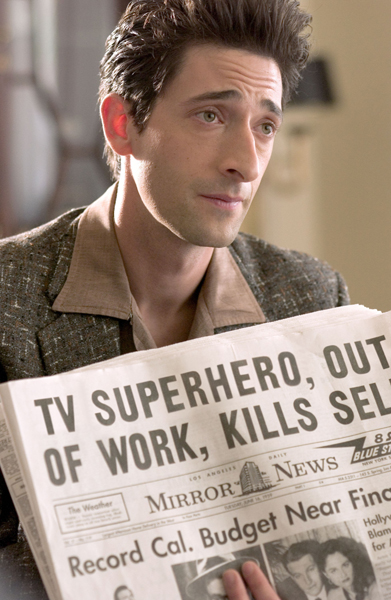

It’s not a huge stretch

then to imagine Coulter’s work making it into the cineplexes. The project

that he chose to make the leap into movies is the nostalgic Hollywood

mystery Hollywoodland, the story of a tough noir detective named

Louis Simo (played by Oscar winner Adrien Brody) who is hired to

investigate the mysterious apparent suicide of George Reeves, the actor

who became a star playing Superman in the 1950s television show.

Originally taking the job for a quick buck but not believing, Simo

uncovers a tangled Hollywood web which somehow involves Reeves’ married

lover (Diane Lane),

her studio-boss husband (Bob Hoskins), Reeves’ gold-digging fiancée (Robin

Tunney) and a smiling but shady studio enforcer (Joe Spano). It all

becomes a fascinating and atmospheric look at Hollywood in the waning days

of the studio system and the allure and

pathological need for fame and stardom.

Coulter was nice enough to sit down with us a couple of weeks before the

film’s release to tell us about his career and the movie.

Before we get to the

movie, I just wanted to ask you a few questions about your TV background.

I believe you directed and were a producer of one of the first episodes –

or perhaps it was the first episode – of

The Sopranos, as

well as doing many others…

Well, it was actually the first season. It wasn’t the first episode.

That was David Chase. That was the pilot. The first season I was a

producer. Once I directed my episode, which was episode five, actually –

the fifth episode in season one – I was asked to stay on as a producer. I

continued on as a producer that season and directed another episode and

then was a producer of the second season.

When you were making it

did you have any idea that it would explode into the cultural force that

it became?

No

idea whatsoever. No idea. We really didn’t know if people would respond

to it or not. We thought it was great. But there was absolutely no

inkling that it would have any success, much less the success it

had.

You

also directed quite a few episodes of

Sex and the City,

which I thought was interesting because most of your other work is very

dramatic. What was it like working on the show and is comedy easier or

harder to pull off as a director?

You

also directed quite a few episodes of

Sex and the City,

which I thought was interesting because most of your other work is very

dramatic. What was it like working on the show and is comedy easier or

harder to pull off as a director?

Yeah. Well, with those actresses it’s pretty easy. And with those

scripts. You know, I don’t really change how I work that much. Depending

even on the material, it doesn’t really change how I work. So I didn’t

find it harder or easier, just different. I do think good comedy is

extremely hard to do, however. I do think that there is some difference.

I’m being a little bit disingenuous, because it is a different thing. My

method of working is really different. But it is a different process and

I think it is hard to be… in editing it’s one of the hardest things,

actually.

Many of your TV shows –

like The

X-Files, the Sopranos, Six Feet Under, even Sex and the City –

were not standard TV fare and known for their cinematic feel. Why did you

feel now was a good time to make the jump to movies? How is it different?

Right, well you know for one thing, it really wasn’t… it was just that I

saw this script and I wanted to do it. That was really the deciding

factor. I was not at all displeased or frustrated with doing television.

I was – as you say – working on the best sorts of things. And those

things are so cinematic in their own right and allow a director a good

deal of freedom. I had such a great relationship with David Chase and the

writers there that I felt very, very comfortable there. It was just

simply that I read this script and I was really taken by it. I wanted the

chance to – pardon the cliché – flex some muscles that I hadn’t had a

chance to flex as a director in television.

How familiar were you

with the George Reeves story before the screenplay, and what intrigued you

about his life?

I

was really not very familiar. I was, like many people, aware that he had

allegedly committed suicide. But I was not really at all aware of the

other theories that grew up after his death – that kind of spun from that

moment. The various theories about what might also have happened that

night, instead of suicide. So I was fairly innocent, to be honest. I

think what drew me was a combination of things. The original script by

Paul Bernbaum; the way that he had found to tell a true story and yet he

found a way to dramatize it and still manage to hold onto a great deal of

what was actually theorized had happened. It’s also a wonderful milieu

– Hollywood in the fifties. The slow death of the studio system as it had

existed in the thirties and forties and the rise of television.

By

weird coincidence, your movie and Brian DePalma’s

The Black Dahlia are

coming out at about the same time. What is it about these old

Hollywood

mysteries that are so fascinating?

By

weird coincidence, your movie and Brian DePalma’s

The Black Dahlia are

coming out at about the same time. What is it about these old

Hollywood

mysteries that are so fascinating?

Well, it is a repository of most of this country’s – and places all over

the world – it’s a repository of people’s dreams and fantasies about how

life might be. At the same time, I think everyone who thinks about this

as perhaps more glamorous, more exciting, a sexier way of life – I think

people also like to see that when things aren’t working so well in that

world. I think they like both – the glamour and the allure and the notion

that perhaps it’s not so glamorous. In fact people suffer the way normal

people do and have secrets and do things that are not always good. I also

think, too, that people are in this case fascinated by the fact that these

people are human. They have issues that they have to deal with that

resemble the drama.

It’s tough because it

has never been solved what happened to Reeves that night, so I thought it

was interesting that in the film you show three different dramatizations

of what possibly happened. You kind of get an idea of what the film

believes probably happened because of the order they were shown, but how

important was it to you to leave open all possibilities?

I

think that’s a very good question. The answer is we were very interested

in doing that; partially because that’s the truth. The truth is, in its

essence, that no one knows exactly what happened that night. No one who

has admitted it was in the room when George died. There are various

things that are unexplained to this day. Why, for example, it took 45

minutes to call the police after his death. There may be a completely

logical explanation. I wasn’t there. Why did all the stories of the

people who were there match exactly? Maybe because that was the case – or

maybe because they all agreed upon it. This is how conspiracy theories

spring up. Because no one really knows the truth except the people who

were there, and we don’t know if they are telling the truth. So that

enduring mystery, which to this day is still, by some, considered to be

unsolved, is something that we didn’t want to change. It’s fascinating.

After being immersed in

the mystery for so long, do you have an opinion on what really happened?

Well,

I probably do, but all of us that worked on the film are reluctant to say,

for a simple reason. We might be considered to be the experts, given our

position. The truth is we’re no more expert – perhaps less so – than

those people who have really pursued this with a vengeance. We are afraid

that our opinions will be not only be taken as expert, it will taint what

the audience thinks when they go into the movie. The truth is, quite

honestly I feel like any audience member’s opinion is as valid as mine. I

don’t want to sully their opportunity to have that opinion.

Well,

I probably do, but all of us that worked on the film are reluctant to say,

for a simple reason. We might be considered to be the experts, given our

position. The truth is we’re no more expert – perhaps less so – than

those people who have really pursued this with a vengeance. We are afraid

that our opinions will be not only be taken as expert, it will taint what

the audience thinks when they go into the movie. The truth is, quite

honestly I feel like any audience member’s opinion is as valid as mine. I

don’t want to sully their opportunity to have that opinion.

Many of the characters

in the film were real people; however the central character of Simo and

those immediately around him – his ex-wife, son and girlfriend – were all

fictional. Why do you think it was important to have these imaginary

characters to ground what really happened?

For exactly that reason. To ground this. To give us a way into the story

but without being bound to the absolute straight facts, which are not

always the most dramatic facts. Really, I think Paul’s intention in the

beginning, and certainly ours once I got involved, was to make a dramatic

film inspired by the facts of the case. But unless you’re making

an actual bio-pic – in which case it’s not always going to be the most

dramatic film, there’s a certain point when one wonders if you’re not just

making a documentary. In this case we tried to stay as close to the facts

as we knew them as we could, with allowances for dramatizing certain

things. The character of Louis Simo, who is played by Adrian Brody, that

character gets us not only way into the story, but gives us another

character whose own story reverberates with the Reeves story. Resonates

with it. As he becomes more interested in Reeves as a man and more

empathetic with him, I think that also allows us to understand Reeves a

little better.

On the other hand, from

what I could tell the film was pretty faithful to the facts of the case.

I know you were not trying to do a straight bio-film, but… I mean, for

example, I am from

Philadelphia

and I just saw

Invincible. I lived

through the Vince Papale years, so while it was a nice enough film I know

for a fact that a lot of liberties were taken with the storyline. How

important was it to stay true to the crux of the story?

I

would say extremely. My feeling was this, even though I knew we were not

making a bio-pic, even though I knew that this was a dramatic film and

that inevitably we’d have to drift from the facts, I felt that we needed

something as a guiding principle. Otherwise it seemed to me everything

was up for grabs. Why not make Toni a man? Why not make Reeves a man

whose only interest is in not women at all, but just in stardom? Why give

him an affair at all?

At a certain point, it

really unravels completely. I felt like if the truth – as we discover it

and understand it – was the guiding principle, at least we had some spine

to the story on which to hang things. Also, out of respect for Reeves.

Frankly, this man it seems suffered in his own life, feeling that he was

not given his due. We didn’t want to be guilty of the same thing. Now

there will be people who dispute things that we did and inevitably there

were facts that either we simply didn’t know or our sources were

mistaken. Or simply didn’t know e ither.

Those facts of his life are quite in dispute. Different sources often

disagree and sometimes a single source will disagree with itself if you

read it really carefully. So there’s a lot of conjecture about what

really happened that night. When George met Toni. Where he met Leonore.

When the affair began. Was Toni really married? All kinds of things that

people don’t seem to know the answer to. Unless one wants to become a

researcher, you have to take the research of others as fact.

ither.

Those facts of his life are quite in dispute. Different sources often

disagree and sometimes a single source will disagree with itself if you

read it really carefully. So there’s a lot of conjecture about what

really happened that night. When George met Toni. Where he met Leonore.

When the affair began. Was Toni really married? All kinds of things that

people don’t seem to know the answer to. Unless one wants to become a

researcher, you have to take the research of others as fact.

Period pieces in

themselves add a whole series of complications as well. I thought it was

interesting that while the movie definitely had the feel of the 50s it

also sometimes felt rather modern. Is it difficult to immerse a film in

another time and place?

Actually, I think you put your finger on exactly what I was intending to

do. That was to make it feel like the 50s, but to also be clear that the

50s – particularly the late 50s – were the beginning of the modern age.

So it was never my intention to make a so-called dusty and slightly musty

period film at which you look as if it’s in the distant past. Like some

old tale that is barely remembered. No, this is in many senses a

contemporary story. We used a contemporary score. I was not interested

in doing a homage to period film. In fact, we made every effort to

make 1959 feel like the modern world. After all, if you lived in 1959, it

didn’t feel like a period film. It just felt like the modern world. So

that was intentional. The world of George Reeves was intentionally meant

to feel a little bit – part

of it is earlier, and

part of it was that Reeves himself emotionally seemed to belong to an

earlier era – so we tried to give his side of the

story

a little bit of a period feel than Louis Simo’s side, which was meant to

be the modern world.

story

a little bit of a period feel than Louis Simo’s side, which was meant to

be the modern world.

I really thought Adrien

Brody was amazing in the role of Simo. The movie had a lot of funny

lines, but I have to admit the biggest laugh in the screening I saw – and

granted I was with a bunch of film critics – was when Reeves’ agent tells

Simo that Reeves was the classic Hollywood leading man, without all the

“squinting and mumbling.”

Yeah, he says, “He has a real movie star face, not like the ones today

with the squinting and the mumbling…”

Was that a little wink

at Brody?

(laughs heartily)

Well, not necessarily. No, I think it was really a wink at

what Art Weismann himself would have thought, and George, too. The modern

world. Again that difference between the world that Simo lives in and the

older world of George Reeves’ acting style being forged in the late

1930s. So his acting was a bit… what we would think of as more stylized

or stiffer. The world of Louis Simo [was] of course the world of

Montgomery Clift and Marlon Brando and the other actors who came along in

the late 40s and early 50s, who were the squinters and the mumblers. We

just felt that Art Weismann… It’s a wonderful line, actually, written by

Howard Korder, who did some work later on in the script. He didn’t get

credit but it was wonderful work. It was just a desire to get across that

Art really belongs to another generation.

I was also very

pleasantly surprised by Affleck as Reeves. I have to admit I didn’t see

it when I first heard the casting, but he really nailed the role. How did

you know he’d be right for the part?

I

met with Ben. I came out to Los Angeles and met Ben and Diane on the same

day. It was just, he exuded a certain kind of charm that George was known

for. He had a very deep interest in the whole project and the film and

the script and George. He’s of course known – and it’s true – that he’s a

highly intelligent man that also seemed to have a certain kind of bearing

and literal size and so on that I thought could be moved very close to

George. In terms of just similarities – physical similarities, even

though we had to do some work with Ben because in many ways he doesn’t

resemble George. We did some very subtle prosthetics and so on that you

really can’t see. He had to gain weight and so on. But it was that

sense, the sense that he understood the man. Ben has a certain ability I

felt, particularly with the clothes and so on, to feel like a man from the

past. A kind of older-style

Hollywood star, which is something I wanted. He had this sort of patina of

glamour about him that I thought was right for George. Particularly for

what George aspired to.

Diane

Lane was very brave in her role as well. For example, in that late scene

with Bob Hoskins when she allows herself to look so haggard – most

Hollywood starlets won’t do that. What do you feel she brought to the role?

Diane

Lane was very brave in her role as well. For example, in that late scene

with Bob Hoskins when she allows herself to look so haggard – most

Hollywood starlets won’t do that. What do you feel she brought to the role?

She was seen with a great deal of makeup in that scene. What’s so

courageous is that she allowed herself to be aged much older than she is.

She actually looks the way she looks in the opening scene where she meets

George. A very glamorous, beautiful woman who seems ageless. We slowly,

with the help of Linda Dowds, a wonderful makeup artist, aged her

throughout the film, so that when that moment comes it’s a shocking

moment. In truth, she’s aged herself about ten years in that shot.

The movie has

apparently been in the works since 2001 and you have been involved since

2003. How does it feel to finally have it getting out there?

It’s wonderful. I must say it’s a thrill to have the film finished and

out there after hard work on the script and trying to make it all that we

thought it could be and finally getting the actors together that we

wanted. I’m excited to see it out there in the world and let people share

that story with us which we were so enamored of, honestly, and so

interested in trying to put out there. Just really out of respect for

Reeves.

Now that you’ve made

the move into films, do you think you will stick with it or will you be

going back and forth between movies and TV?

I

hope the latter. I don’t really have any kind of issue doing either one.

Where I hope to be is where the best work I can find is. Work that of

course suits my own talent the best. I’m really hopeful that I can

continue to move back and forth and that way not have to wait four years

between movies.

Do you have any new

projects in the works?

I

wish I could say yes, but I’m right now actively looking. It’s hard to

find things that are in television on the level of The Sopranos or

Sex and the City or those shows. And it’s very hard to find movie

scripts that are on this level. I’ve painted myself into a corner and I

just have to keep looking.

Email us Let us know what you think.