Copyright ©2007 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

February 25, 2007.

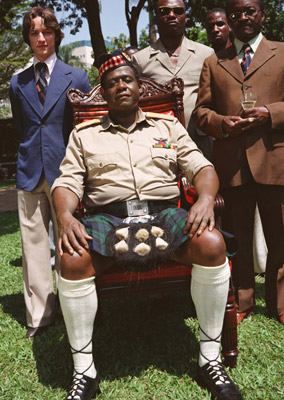

For Forest Whitaker,

it's been a long strange ride from the start, creating the character of Idi

Amin for his last film, The Last King of Scotland. With this year's

Best Actor nomination, he's favored to win – something he never expected

upon taking on this role.

But like Idi Amin,

Whitaker has always defied expectations, especially when he co-starred in

the award-winning The Crying Game – where he played a man in love

with a pre-op transsexual, much to everyone’s surprise. Whitaker has been an

actor that has defied such concerns and racial stereotypes as well.

How did this project

begin?

Producers Lisa Bryer

and Andrea Calderwood gave me the book about five years ago. I liked it and

we talked about it, but there wasn't a director. It wasn't until years later

that Kevin [MacDonald] became involved, and when Kevin became involved I met

with him and worked with him and he decided that he wanted me to play the

part.

What kind of research

did you do?

I started first in LA,

because I started working on the key Swahili, which I thought was really

important, because I wanted to really start to believe in my head that

English was my second language. Then I start working on my dialect and the

accordion. Then I started studying all the books – so many books about him.

The documentaries, the tapes – there's so much film footage, because he was

a showman. He loved the press, so you can get so much material.

Then when I got to

Uganda, I met with his brother, his sisters, his generals, his ministers,

his girlfriends. Everybody in Uganda who's like 20-30 or above, they have a

personal experience with Idi Amin. They've seen him. They watched him on the

streets. They knew him. It was just 1979 when he left power. You talk to

everyone and they're explaining their views and opinions of the man, and

you're traveling around and eating and understanding the customs. I had a

Ugandan assistant, Daniel, who was helping me get into the culture and try

to make it my own.

During

your research process, what helped you round out the character?

During

your research process, what helped you round out the character?

I knew he wasn't the

caricature I had seen him be. I knew he was a complete human being. I had

seen an image of what they projected to me. I had to take things like that

with a grain of salt. The minute you start to define the guy, the minute you

decide, “Oh, you know, when he comes in the room he likes to use the

bathroom first. He likes to take showers in the cold. He doesn't like to go

to this theater.” Then al of a sudden the person becomes more complete. I

knew that I didn't have any impressions like that, so for me it was kind of

an opportunity to try to explore it and understand that.

What was your reaction

to playing the part of Idi Amin?

I didn't have an image

of him other than a sort of poster stamp image of this sort of mad

dictator/general or whatever. So, when I was looking at the project, it was

an opportunity to kind of explore. As an artist it was a great opportunity

to get to play a character like that and to explore him as a person would

help me grow. So I thought it was a great opportunity.

What was the most

difficult part to becoming Idi Amin and what do you think ultimately turned

him into the person he became?

Trying to find the

spirit of this guy took a lot of work. I worked really hard trying to figure

it out. I wanted to make it like anything I do. The way I believe this man

would behave. It's really like accessing the spirit of the person.

For me, acting is a

little bit of a spiritual experience, so for me I'm deeply searching for a

connection inside of myself to look for the places. I'm also looking outside

of myself to pull down energy inside of myself to play the character. So

that's a process that takes work.

Was there a

particularly difficult element you had to wrangle with?

There were so many

technical things that I had to master. I was lowering my voice to his

register. I was trying to understand the dialect. Actually I think all that

stuff helped me to figure out the character. It was an aid. At least I had a

direction I knew I was trying to go in. I'm trying to think what I felt the

most difficult… It was just a process. I was just continually searching, so

I never stopped for a concern.

Even while we were

shooting, if we were off and we would go to the top of the hill, I would

say, “Oh, I want to go to that mosque, because he used to go to that

mosque,” or “I'm going to go meet this guy because he knows him,” or “I'm

going to go call his son, and maybe he'll meet me.” Up until the very last

day of the shoot, I was still doing work and research. So that difficulty

problem, it was something I was continually searching for throughout the

whole entire process.

What

was it like meeting his family?

What

was it like meeting his family?

I met his brother and

sister in Arua. I flew up there. They were really apprehensive at first.

First we had to go meet with this minister, and I met the guy. I didn't know

he was a minister at the time, but he was going to bring me to him, and then

finally he decided that we were okay to bring us there. Then his brother

wouldn't talk to us, and then finally I pulled out this letter that I had in

my pocket that was from the president's office saying we have permission to

shoot a film there, and for him that was the most important.

Then finally, we sat

underneath this tree and he started telling me stories about Idi Amin

growing up. He was extremely poor, his sister, the house they lived in was

full of mortar holes. It had been blown up by the troops that came in after,

and he was just trying to survive, but he helped me a lot, figuring the man

out.

What do you think made

him so likeable at times?

I wasn't trying to

make him likeable. If you look at all those tapes he's an extremely charming

guy. He was extremely well liked. The reason they were trying to destroy

him, the reason he made the coup, was because he was getting so popular with

the people. Obote, the president, wanted him out, wanted him away. He was so

popular. He was popular with the British. The British brought him to

Sanhurst to train him, the Israelis taught him paratrooping. He was very

popular.

I think even as the

atrocities started to happen, as the paranoia started to happen, he was

extremely popular, even still with the press. They were more interested on

reporting on his antics, his partying, his behavior, or his costumes, rather

than reporting on what was going on in the country until it was really deep

into the horrors of his reign.

What

are the most important things you learned about the culture and the man that

most Americans don't understand?

What

are the most important things you learned about the culture and the man that

most Americans don't understand?

I think that most

people see him as this sort of savage who had nothing to offer, but if you

talk to Ugandans, they have a very mixed point of view on Idi Amin. One

person can acknowledge, even say that he killed his cousin, and then on the

other hand say, “I wouldn't be in this hotel. I wouldn't be in this chair. I

wouldn't have this job if Idi Amin hadn't been here.”

This was something I

was trying to struggle and understand, something I didn't know. I didn't

know the details. I didn't know what the behind-the-scenes issues were. I

spoke to an East Indian man, he was a scholar actually, and he had amazingly

positive things to say about Idi Amin. He was third generation Ugandan. He

thought he had helped the country immensely. So that was confusing to me

too, because he did kick the Asians out of Uganda, he gave them like 90

days. But they did control like 80-90% of the economy.

When they were kicked

out, the Ugandans had to scurry around and figure out how to run their

businesses, and they were floundering for quite some time. But today, they

are businessmen, and they really weren't before. So, as he explained these

things to me, and people explained things to me… Like even theater. It was

all run by the ex-patriots. When he kicked the English out, he started a

radio station and auditioned plays and then he took the plays and put them

into theaters, and so Ugandan theater began to flourish. They have a lot of

mixed feelings, at the same time knowing that hundreds of thousands of

people were killed.

And what about the way

their society functions?

For me Uganda exists

inside the people. It's a very green, lush place, and as a result there's

not a whole lot of old, ancient buildings. Because of the climate itself –

it destroys them. You find it by going to people's homes, eating with them

and listening to them. Watching them interact with their children, and the

generosity that they have, trying to be friends and open their lives to you.

For me that's what I got the most.

The fact that they

took me around to so many places and they took so much care, it was really

important to them that I understand as much as I could the place and the

people. I left there with a deep feeling of love. Other things I didn't know

much about the resistance army in the north, I didn't know a lot about Coney

and the problems there. They've worked through more than other countries in

Africa. The issue with AIDS; UNICEF has done a program that's really helped

it out. It's a budding economy of people who are striving. The Ugandans are

really into education and trying to educate and move forward. I wish I could

summarize it all perfectly.

How

did you feel about inserting a real person into an otherwise fictional story

that centers around a white protagonist?

How

did you feel about inserting a real person into an otherwise fictional story

that centers around a white protagonist?

The Idi Amin story is

very complicated. He's a product of western intervention. He's a product of

it because he was trained by the British as a soldier. They brought him to

different places and advanced him in the country and even put him into the

presidency, so it's very difficult to put him into this story without

dealing with that. I think that Nicholas represents the west, the ravaging

west that just comes in. As Idi Amin says, “Did you just come in here to

screw and to take away? Is that what you came here for?”

Idi Amin's legacy, and

the reason he lives in people's minds, because there are other people who

have killed more people, there are others in Africa as well as western parts

of the world, I think the fact that this man, this black man stood up and

said, “British, get out, Israelis get out,” is why people are so fascinated.

I think as a result it's important to take this character and move him in

and understand what he was toying with. He was brought up in Africa, but he

was embracing certain traits from the west, certain hedonistic features from

the west, and it's a lot about this clash of cultures.

There was a lot of

criticism of films that came out about South Africa in the late 80s and

early 90s that they were only through the point of view of white characters.

Did you have any feeling about this?

Obviously it's based

on a book, but I think in this case the story is about foreign culture and

the clash of culture and about cultures coming in and imposing their

thoughts and their wills and what kind of monsters are created from that. In

this case I think that Nicholas is not brought in as a hero. He's a very

flawed character. And I think that what it does do is that you do go into

the intimate side of Idi Amin.

There have been maybe

three other movies made about Idi Amin, but I think in this case you

actually get to go inside and listen to him. Nicholas's character in some

ways has to react to the world that he walks into. So in some respects it's

not just about Nicholas's point of view, many times in the scenes it's about

Idi Amin and what he's trying to accomplish and do and feeling, his own

fears, his own paranoia, his own issues.

Once at a film

festival you said that you wanted to speak to the director of

Babel, but

that you were a little shy to do it. As a filmmaker yourself, do you

consider yourself a shy person?

I think I'm a little

more an internal person. I don't really know him, and I really admire his

work, but I felt a little awkward just going up and shooting on whatever is

going on and stuff. I went to that movie because the actor had asked me to

come see it. I thought he was brilliant, actually, and to come talk to him

afterwards. So it was great.

Can

you speak about your longevity and some of the things that may have helped

with your career?

Can

you speak about your longevity and some of the things that may have helped

with your career?

Yeah, it's been a

while, and I've been going for a long time, it's cool. I think I've always

been trying to do stuff that I believed in and that affected me. I was lucky

that the things that I chose did well. Because some of them were kind of

risky choices. No one wanted to do The Crying Game when I was doing

it. Nobody financed it. Nobody wanted to be involved with it. People were

trying to get me not to go to Manila to do Platoon. Nobody wanted us

to go. I think it was chancy. I love Jim Jarmusch, but with a character

where you don't speak? I don't speak for most of the movie [Ghost Dog:

The Way of the Samurai]. With Idi Amin, the question's a very relevant

question. People would ask me, “Why would you want to play this character?

People could look at it as why are you showing this monster from the African

continent?” But I have my point of view on it, and it could ultimately be a

good thing, so I just made my choices by my heart, really.

After consuming such

an extreme character, how do you come down and become Forest Whitaker again?

At the end of the

movie the last day, I had a little bit of a ritual. I kind of take a shower,

try to wash the character away. I try to yell his voice out of me. I try to

get my voice back. I think in this case I was lucky. I don't remember what

movie I did, but I had another movie I had to go do, so when I got home I

started working on another character, and so that helped me get rid of him.

That was really important.

Is it hard to find

parts that give you this kind of richness?

This kind of

character, he's so unique, you don't find a character like this too often.

I've had about four movies come out. I'd stopped acting for about four

years. I was just directing [and] producing, and so then I started about two

years ago to start acting again, I did all different kinds of movies. I did

an animated thing with Spike Jonze, Where the Wild Things Are, based

on the book. I did this movie in Mexico just recently which is kind of an

action thriller with William Hurt and Dennis Quaid. It's about an

assassination attempt on the president, told through the point of view of

five different people in the same fifteen minutes. I did a Chinese parable

with this young filmmaker, Jieho Lee. I play Happiness and Kevin Bacon plays

Love and Brendan Fraser plays Pleasure and Sarah Michelle Gellar plays

Sorrow. It's about how our lives all interact when Happiness meets Pleasure

and then meets Sorrow and what happens in our lives. So I've been just kind

of doing whatever I feel. Hopefully they'll do okay.

So there is a kind of

spiritual thread in the characters you pick…

I think that we're all

people on a journey, so every character I play is going to have some sort of

that.

How

do you feel about the Oscar buzz for you for this film?

How

do you feel about the Oscar buzz for you for this film?

I'm happy that people

like my work enough to say that, and I hope it makes people go and see the

movie, but other than that I have to let it be. I was working on The

Shield earlier this year, and everyone was saying that I'd be nominated

for an Emmy or win an Emmy. Everybody would say, “Oh, if this doesn't, I'm

going to be so upset.” I wasn't even nominated.

Were you upset?

No, that wasn't me.

That was a press person. No, I was off doing a movie somewhere, I think I

was in Mexico.

What made you leave

the acting and go to directing and then go back to acting?

When I left college I

started directing my friends on stage, and then I started directing music

videos. Originally when I first left college my first professional job was I

wrote a script in college. The first thing I was offered professionally, so

it's a part of me. So, when it happens it happens. I'm just telling stories

and stuff.

Do you feel that

you've become a better actor as a result of making your own films or vice

versa?

I think you're right,

I think that acting helps me as a director because it helps me understand

the actor and the acting process. I think directing can be detrimental to

acting for me. I'm already kind of a considerate artist. When I'm working on

a movie as an actor and there are problems on the set, I think you can

become too reasonable. I think people want you to at least know when to

stand strong. Sometimes you say, “Now I've got to get the day. Now I've got

to move the location. The lights are gone, oh, I understand,” instead of

being like, “We need to go one more time,” because they don't know that that

one more time happens, it could be something extraordinary. So I can lose

sight and be like, oh, okay, well, I'll be in my trailer, when you guys work

it out, just call me.

You mentioned being a

spiritual actor. Do you see Idi Amin as someone who was spiritual or just as

someone who considered himself to be spiritual?

I think Idi Amin in

the classic sense of spirituality became more in touch with his belief

system when he went to Saudi Arabia when he left Uganda. He became much more

of a practicing Muslim then. The legend is that his father was a Christian

preacher; he converted to Islam when he went to a menthe plantation and so

did his father. Idi Amin all through his reign referenced spiritual things.

Idi Amin would always say “I had a dream. I had a dream they told me to get

rid of the Asians, I had a dream they told me they needed to name all the

lakes this.”

So

all through his reign he was always saying things like that, just like, “I

know the moment of my death. No one can kill me.” And that's true, he

believed that. You'd see him saying that in the David Cross interview. He

truly did believe that, I don't think it was something he was just making

up. He believed that he could see his death. He believed in his dreams and

he believed in his destiny. Sometimes I think he made up certain things but

that I think was the key to his personality and his spirit.

So

all through his reign he was always saying things like that, just like, “I

know the moment of my death. No one can kill me.” And that's true, he

believed that. You'd see him saying that in the David Cross interview. He

truly did believe that, I don't think it was something he was just making

up. He believed that he could see his death. He believed in his dreams and

he believed in his destiny. Sometimes I think he made up certain things but

that I think was the key to his personality and his spirit.

Anything to share

about working with William Hurt again?

Yeah, I had a great

time. William's good in this movie, too. We didn't get to do a lot,

especially in this movie. The stories were so separate. I play a tourist

who's there and sort of tapes this event and has this tape…

Are you going to be

directing next?

No, I haven't figured

it out.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.

Features

Return to the features page.