Copyright ©2010

PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

August 12, 2010.

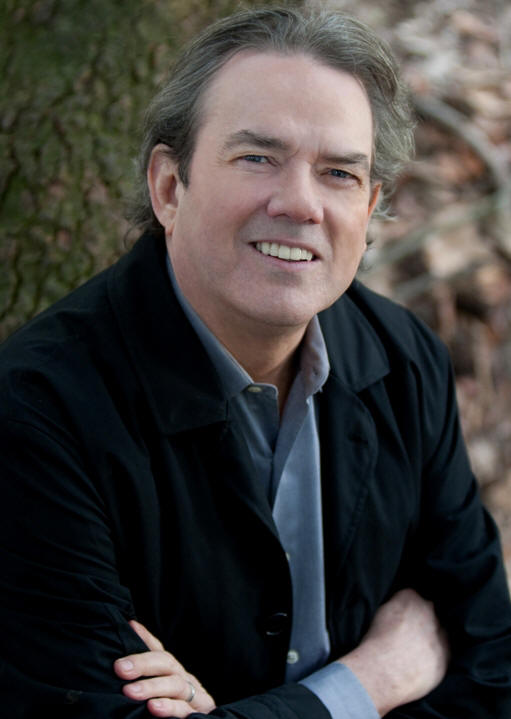

About fifteen years

ago, one chilly autumnal night, I was in a coffee house in Lahaska,

Pennsylvania when a young man—no more than eighteen—suddenly sat down at

an upright piano. “This is an old pop song,” he announced in an apologetic tone.

It was impossible to mistake the first few staccato notes. He launched

into a stripped down version of “Wichita Lineman,” Jimmy Webb’s

plaintive tune about a lonely line-worker trapped existentially among

the solitary telephone poles. If you never knew how beautiful and deep

a pop song could be, you’d have known it that night.

That’s the essence of the music of Jimmy Webb, one of the most

accomplished and prolific songwriters from the past 40 years. Since the

beginning of his career in the 1960s, Webb has exhibited a singular

talent for melding thoughtful, imagery-laden lyrics with sophisticated,

layered melodies.

The foster-child of Tin Pan Alley and Sixties Singer/Songwriter, Webb

matches the emotional nuance of the Gershwins with the direct passion of

unbridled rock. On both levels, lyrically and musically, he has

remained unafraid to take abrupt left turns, to go deep, and to

challenge both the singer and the listener.

Webb’s mature songs with their often curious melodic shifts have seduced

listeners at every one of those turns. “Galveston,” “Up, Up and Away,”

“All I Know,” “I Keep It Hid,” “Didn’t We,” “Highwayman,” “The Moon’s A

Harsh Mistress,” “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” “The Worst That Could

Happen,” “If These Walls Could Speak.” Webb deftly encapsulates entire

lifetimes in a three-minute drama (well, seven minutes in the case of

“MacArthur Park”).

And he’s a triple threat. A member of the National Academy of Popular

Music Songwriter’s Hall of Fame, Webb is the only artist to win Grammy

awards for music, lyrics and orchestrations. His passionate string

arrangements, in particular, reveal an intelligence and maturity matched

only by the late Nelson Riddle.

“A lot of the imagery in my songs is visual and based on a kind of

photographic memory,” explains Webb. “I try to place myself back in a

scene or situation. I have a very vivid grasp of those details from the

past. I was heavily influenced by a book by John Gardner called The

Art of Fiction, basically an instructive book for young writers.

It

talked about imagery a lot, about word choice and avoiding

clichéd ways of

describing things, searching for new ways to describe them. I paid a

lot of attention to that book.”

Over the years, some powerhouse singers have lent their talents to

Webb’s seductive tunes, among them the 5th Dimension, Linda

Ronstadt, Tony Bennett, David Crosby, Glen Campbell, the Supremes,

Rosemary Clooney, Art Garfunkel, Sinatra and James Taylor. From John

Denver to REM to Streisand, performers of myriad styles have been unable

to resist his brilliant songbook.

On his new CD Just Across the River, Webb performs 13 of his

songs, both seminal tunes and some lesser-known gems, with a notable

array of musical soul mates. Some—like Billy Joel and Jackson

Browne—have never recorded Webb songs but have spent decades admiring

his talents. Others—like Ronstadt and Campbell—share a long history of

singing Webb’s tunes in what many consider definitive versions.

“I wouldn’t want anyone to think that this album is a marketing ploy of

any kind,” insists Webb. “The celebrities who were involved in this

project were all friends of mine who bonded with the material and wanted

to be a part of this project. It was all done out of a sense of fun and

deeper than that—a joy and love for the material and for each other.

“It’s like a family getting together to make a record,” he adds. “It

would be easy to dismiss as a commercial idea. Fortunately it’s the

real thing. We don’t feel self-conscious about what we did at all. We

think it comes from a very real place.”

Campbell’s early career was rife with Webb hits, among them the

haunting “Galveston” and “Wichita Lineman”—today, considered pop

standards of the highest order. On this CD, Campbell duets with Webb on

another of his early hits, “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” surprisingly

in their first time singing together.

The languid new arrangement—more Memphis than Nashville—conjures up

memories of the late Brook Benton. Considered by Sinatra to be the

greatest torch song ever written, “Phoenix” is the third most performed

song from the past 50 years.

In the 80s and 90s, Ronstadt recorded eight Webb tunes, including the

bitter “Easy for You to Say” and one of his most elegant compositions,

“Adios,” written partially for her. “I wrote ‘Adios’ when I left

California as kind of a goodbye song for a whole epic chapter of my

life,” recalls Webb. “It very rapidly became a Linda song, and she

actually helped me co-write some of the lyrics on it. We wrote things

like, ‘I’ll miss the blood-red sunset,’ which she liked very much.”

In the 80s and 90s, Ronstadt recorded eight Webb tunes, including the

bitter “Easy for You to Say” and one of his most elegant compositions,

“Adios,” written partially for her. “I wrote ‘Adios’ when I left

California as kind of a goodbye song for a whole epic chapter of my

life,” recalls Webb. “It very rapidly became a Linda song, and she

actually helped me co-write some of the lyrics on it. We wrote things

like, ‘I’ll miss the blood-red sunset,’ which she liked very much.”

Ronstadt and Webb close Just Across the River with a pensive take

on “All I Know,” a hit for Art Garfunkel in 1973. “She worked very hard

on that,” says Webb. “You can hear it. It was only a couple of weeks

before that that she had officially retired. She held a press

conference in Berkeley and said, ‘I’m not going to be able to sing

anymore.’ There was no way in the world I was going to ask her to do

this and we ended up, without any comment whatsoever, just sending the

musical track to her.

“Being Linda, she wrote back within a couple of days, ‘Okay, I have to

try this.’ It really turned out to be one of the most singularly

beautiful performances of a career that certainly has had more than its

share of highs. If I may say so, I think her appearance on this album

is a high point.”

Joel duets with Webb on a song the Piano Man has long admired, “Wichita

Lineman.” One might expect Webb’s rough-hewn vocals to pale next to

Joel’s still ringing tenor—but even this version provides insight into

Webb’s own interpretive strength, his bold emotionalism and deep

connection to his own lyrics. “I actually find that my voice is getting

stronger,” he observes.

Jackson Browne weighs in on one of Webb’s older tunes, the wry “P.F.

Sloan.” Webb first heard Browne covering the song in the early 1970s at

a club in LA. Country stalwart Willie Nelson, who sang on Webb’s

“Highwayman,” does a driving turn with Webb on “If You See Me Getting

Smaller,” a tribute to Waylon Jennings, who had a hit with it.

Vince Gill (a fellow Oklahoman), Mark Knopfler (who also provides

sensuous lead guitar on “Phoenix”), Michael McDonald, J.D. Souther and

Lucinda Williams—adding a woman’s response to Webb’s call on

“Galveston”—round out the bill.

The newest song on the CD is “Where Words End,” a prime example of

Webb’s uncanny ability to craft imagist lyrics and seductive melodies.

Written last year at the behest of Johnny Rivers—who was an early mentor and

friend to Webb—the song describes the singer’s affection for his mother,

whose face appears in “a new constellation.” The song speaks,

ironically, to the impotence of words when emotion becomes larger than

language.

“It’s one of my favorite moments on the album,” admits Webb. “One of the

best jobs Michael McDonald’s ever done on background. He is the best

background singer ever. He’s probably the best lead singer ever,

too. He’s like a surgeon, a doctor, when it comes to that layering of

background parts. He’s appeared on several of my albums. It was another

opportunity to be blessed with this man and his talent.”

The CD’s songs, recorded in Nashville, unite in their overall musical

approach: arrangements reveal a more folkish, country sound, replete

with dobro, mouth harp and mandolin, further emphasizing Webb’s rural

roots and natural voice. Topnotch Nashville musicians include Jerry

Douglass on dobro and Stuart Duncan on fiddle and mandolin.

“It’s home base,” confirms Webb, who is also a member of the Nashville

Songwriter’s Hall of Fame. “It’s anything but strange. It’s kind of

inevitable in a way. If you think of my background—Glen Campbell, the

Highwaymen, Waylon Jennings have recorded my material—there were

country-leaning songs since the very beginning. It’s a very natural

place for me to sing.”

On

this front, the album has the feel of a completed circle which

contributes to its overall emotional power. The listener also senses

that Webb—with stellar assistance—revisits his songbook in a deeply

reflective mode.

Webb and Ronstadt’s closing “All I Know” exemplifies this effect. Her

dulcet voice not only wraps around his but adheres to it, enhancing the

sadness. Stripped of the broad grandeur of Garfunkel’s orchestrated

original, the two voices offer an intimate, mature reading reminding us

that—in the end—Webb’s music has always been about love.

“I don’t feel that love is a perishable substance,” observes Webb. “I

don’t think that it really dies. It may change over time, it may age,

but it doesn’t die. It’s like Einstein’s theory of relativity. You

can’t destroy mass—you can only turn it into something else. And you

can’t destroy energy—it only solidifies. So, I’m a believer in love

lasting forever. I think in some way or other if it was love, it lasts

forever. It becomes part of your DNA.”

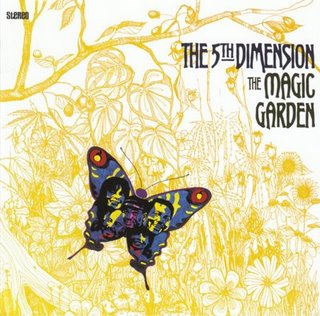

The inventive nature of Webb’s lyrics, sophisticated composing, and

layered arrangements first surfaced on The Magic Garden, a

concept album he created for the 5th Dimension in 1968

(following his eight Grammy Awards for “Up, Up and Away” and “By the

Time I Get to Phoenix” in 1967).

The inventive nature of Webb’s lyrics, sophisticated composing, and

layered arrangements first surfaced on The Magic Garden, a

concept album he created for the 5th Dimension in 1968

(following his eight Grammy Awards for “Up, Up and Away” and “By the

Time I Get to Phoenix” in 1967).

In eleven songs connected by recurring thematic passages, Webb painted the

anatomy of a relationship—moving from romantic illusion to despair. The

song-cycle reflects a plethora of styles, shifts in tempo, ornate

harmonies by the group, and Webb’s signature capacity to write rock deep

into the orchestra.

“It was a very important album for me,” notes Webb. “It was the first

album where I was given the opportunity of doing all the orchestrations,

the horns and strings, and I was working with Bones Howe, who was a

genius. To be honest about it, it was the first time that I had

complete freedom in the studio because before that I was working with

Johnny Rivers. I had always had someone looking over my shoulder.

“So that album kind of represents the first completely autonomous

project I was ever involved in where we really got to do whatever we

wanted to. It turned out that it didn’t sell really well but it hangs

on as an iconic piece. A lot of people treasure that record.”

Part of the reason for The Magic Garden’s continuing

fascination—there is even talk of turning it into a Broadway musical—is

the sheer power of Billy Davis, Jr.’s voice, breathing life into Webb’s

angst-ridden alter-ego. “On my list of favorite singers, Billy’s very

near the top—he’s extraordinary,” notes Webb. “I don’t think anybody

could touch Billy. He was an Otis Redding-class singer.”

“Webb’s lyrics were so deep,” confirms Davis. “We would have to talk to

him about the story—about what he was experiencing—just to interpret the

song.” Especially on “The Worst That Could Happen” and the cinematic

“Requiem: 820 Latham,” Davis tore emotional holes through Webb’s

brilliant compositions.

“At my age now I wish just for a couple of days I could go back and feel

some of the madness that I felt when I was sixteen years old,” muses Webb,

“when I was actually writing ‘Hymns from Grant Terrace’ and ‘Requiem: 820

Latham.’

“I look at those songs now and I think, ‘This thing is pure emotion.’

It’s shameless—it doesn’t even say, ‘Gee, maybe I should be careful

about what I write because someone might read this some day.’ It’s

totally unselfconscious. There’s a purity to it—there’s a rough

finish, uncultured, as if it hadn’t been aged properly. But the raw

material is dynamite.”

Other milestones in pop music followed, including two critically

acclaimed albums for Irish actor-singer Richard Harris: A Tramp

Shining (1968) and The Yard Went on Forever (1969). Webb

concocted another album-full of songs for Thelma Houston in Sunshower

(1969), giving birth to “Everybody Gets to Go to the Moon,” “This Is

Your Life” and “Someone Is Standing Outside,” the latter resurrected by

Patti Austin in 1988.

In 1972, Webb produced and arranged an album of mostly his own tunes for

the Supremes, with Jean Terrell on lead, merging pop, rock and soul in a

rare turn for the trio. The album proffered one of Webb’s most powerful

ballads, “5:30 Plane,” affording Terrell her finest moment on record.

On Reunion, in 1974, Webb produced an entire album of songs for

Campbell. Folk married seamlessly with orchestral music on such Webb

classics as “The Moon’s A Harsh Mistress” and “I Keep It Hid.” In

the 1980s Ronstadt covered these songs, along with

“Still Within

the Sound of My Voice”

and

“Shattered,”

in definitive, symphonic versions.

The following year, Webb returned to the 5th Dimension for Marilyn McCoo

and Davis’ last outing with the group on the album Earthbound.

“It was prophetic,” points out McCoo. “Jimmy was there art the

beginning with the group—Up, Up and Away—and then there again at

the end of our experience with the group—Earthbound.”

Still, the album gave birth to one of Webb's most ethereal compositions,

"When Did I Lose Your Love," featuring McCoo's mellifluous lead and some

intricate guitar work by Larry Coryell. “It’s a beautiful,

beautiful song,” affirms McCoo.

On Watermark (1978), Webb produced an entire album for

Art Garfunkel, with

songs ranging in approach from early rock and roll ballad (“Someone

Else”) to jazz (“Mr. Shuck and Jive”). The Celtic “All My Love’s

Laughter,” a lovely marriage of lyric and melody, featured a glorious

turn by the Chieftains backing Garfunkel’s angelic tenor in a wistful

song about a duplicitous maiden.

In 2003, Webb produced an album of his songs for cabaret singer Michael

Feinstein, reinforcing Webb’s connection to the Great American Songbook

in such contemporary standards as “Time Flies,” “She Moves, Eyes Follow”

and “Is There Love After You.”

Asked to comment on his evolution as an arranger, Webb claims he was

“just learning on the job. I was always interested in establishing a

good, solid basic track, so I was usually over-dubbing orchestra. I

would add instruments as they came into my purview, as I got to see them

and hear them play, and I realized the actual range of each instrument.

“It was an amalgamation of techniques that I picked up from different

arrangers, like George Martin, whom I watched work in the studio. And

of course, what good is an arrangement if it doesn’t actually make the

song sound better? It can be a very flashy arrangement, but the song

shouldn’t get lost somewhere in the muddle. For example, it was very

difficult to arrange Joni Mitchell songs for the Supremes.”

Webb adds that he believes these layered techniques “belong to another

era, really to the big band era when people really were listening to

arrangements, because a lot of big band music was orchestral. Those

people actually heard music at a deeper level. They heard counterpoint,

they heard dissonance, and they heard different voices leaping out.”

Webb alludes to the “great pop hits of the sixties” as influential

examples of fine arranging: “Tony Hatch’s work with Petula Clark and

Dusty Springfield. The Teddy Randazzo arrangements that were done for

Little Anthony and the Imperials. The Burt Bacharach arrangements for

early Dionne Warwick. A lot of the Don Costa stuff that was done in the

60s and early 70s for Sinatra. I go back even further to things like

‘A Summer Place’ by Percy

Faith.

“I was just raised on that stuff, so a lot of my arranging is really an

attempt to get close to some of those sounds—with varying degrees of

success.” Still, Webb did no arranging on Just Across the River.

“To concentrate on my singing,” he explains, “to leave my heart and soul

on the microphone.” Instead, he turned the reins over to producer Fred

Mollin, who also produced the composer’s sparsely arranged Ten Easy

Pieces (1996), a favorite of Webb aficionados.

Ironically, Webb points out that—today—his first album Words and

Music (1970) sounds like a garage band. “I don’t know how we got

things to sound that small,” he says. “Meanwhile, the Beatles and

others were trying to figure out how to get things to sound bigger

and more excessive. I don’t know why we thought the sounds we were

making were big enough to compete, because they just weren’t. It’s all

part of developing your own craft.”

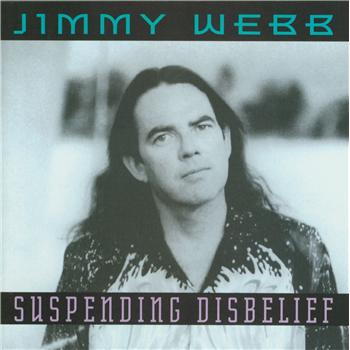

By Suspending Disbelief (1993), Webb had long since perfected the

larger arrangement, even for his own voice: “Those were big and they

sounded good.” He resurrects the saloon lament “It Won’t Bring Her

Back” from that album as a solo on Just Across the River, lending

it a pure country reading. “If I ever wrote a country song,” he

indicates, “that’s it.”

By Suspending Disbelief (1993), Webb had long since perfected the

larger arrangement, even for his own voice: “Those were big and they

sounded good.” He resurrects the saloon lament “It Won’t Bring Her

Back” from that album as a solo on Just Across the River, lending

it a pure country reading. “If I ever wrote a country song,” he

indicates, “that’s it.”

It would be impossible to enumerate the hundreds of songs Webb has

written, produced and arranged for myriad artists over the last four

decades—not to mention his own critically lauded albums, often

introducing fans to long-awaited new material. This year Judy Collins

released a sweeping cover of Webb’s cinematographic “Gauguin,” a

painterly portrait of the tortured Post-Impressionist as a symbol for

the underappreciated artist.

On a similar note, Webb acknowledges the difficulty well-crafted ballads

face in the contemporary music market: “The truth is it’s not a

flourishing area. It’s inversely proportionate to the number of

performers out there who don’t write their own material yet who are

interested in something that really has some traditional craft behind

it. It represents the shutting down of the emotional side of human

nature, which cannot be good.

“It’s why I called my book Tunesmith, after a science-fiction

story about a society where songs have perished and the only available

music is commercial jingles. And jingles have never been more healthy

and active than they’ve been today.”

And that may well be. But fifty years from now, in another nightclub or

café, someone else will sit down at a piano and conjure up “Wichita

Lineman.” And there will be no reason to apologize. It’s a Jimmy Webb

song—and that’s all anyone will need to know.

Mark Mussari is a

journalist and translator living in Tucson, Arizona.

CLICK HERE TO SEE WHAT

JIMMY WEBB HAD TO SAY TO US IN 1999!

Features Return to the features page