Spanish film

director Fernando Trueba has had a long, fascinating career which

has branched out in many directions. He started out as a movie

critic in the 1970s for the newspaper El Pais. He has since

worked as an author, screenwriter, movie director and producer, book

editor and a musical producer. He has won Grammys for his work as

well as the Goya Award, Silver Bear and an Oscar for his 1994 film

Belle Époque,

which won for Best Foreign Film.

He

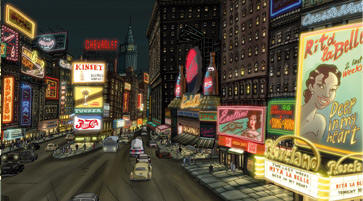

was recently nominated for his second Oscar for Chico and Rita,

his animated love song to the jazz scene of the 1940s and

1950s. Trueba created and wrote the film with well known Spanish

artist and designer Javier Mariscal. The two decided that they

wanted to create a far-reaching celebration of Cuban jazz, as shown

as an intimate and troubled love story between a talented pianist

and the singer who is his muse. The film revisits such jazz

hotspots as Havana, New York, Paris and Vegas and spans years to

tell its heartfelt story.

A couple of

days before the Academy Award ceremony, Mr. Trueba gave us a call to

talk about his film, his love of jazz and his Oscar experience.

You

and Javier Mariscal have been friends and collaborators for years.

How did the idea of making

Chico & Rita

come about?

You

and Javier Mariscal have been friends and collaborators for years.

How did the idea of making

Chico & Rita

come about?

It’s because

we became such good friends that we wanted to make something

together. I always thought that a movie is like making a treat.

You have to put together a great crew and you go far away to look

for some far island where you think you are going to find a treasure

or something like that. Javier Mariscal and I, we wanted to do some

work together, to share more time, to really collaborate. Chico

& Rita was the way of doing this. We thought about what things

we like the most and the first thing was music. Jazz. Cuban

music. Cuba. It just started like this. From this we started

working on a script, story, characters, etc.

Music has

obviously been just as important to your career as filmmaking has

been. How exciting is it to get the chance to mix your two passions

so completely as you do here?

I’ve done that

before, when I did Calle 54 ten years ago, a documentary on

Latin jazz. As I’m getting older, I always try in my movies to put

the most possible things that I really like and enjoy. I don’t like

to make movies about people that I dislike. I would never make a

movie about Margaret Thatcher. I think that’s horrible, for me it

would be a nightmare to do a movie about a character like this. So,

when I do movies, I try to put in them all the things that I like –

music, love, New York, Havana. Also, Chico & Rita is

[about] my love

of classic American cinema. I think that’s there all the time,

also, the classical narrative ways. So, that’s it…

As a jazz fan,

how much fun was it to recreate such legendary scenes as Havana, New

York, Paris and Vegas in the 40s and 50s?

It was a lot

of fun. One thing that was very exciting was mixing the fictional

character with real characters like Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie

or all the real musicians that we squeezed into the story. That was

a lot of fun. Also, the production of the music of the score of the

movie is part of the script, in some ways, because the story is told

through music, most of the time. That was one of the nicest things

about making Chico & Rita, for me it was a very exciting,

very strong work. Very hard work sometimes, but at the same time, I

would start tomorrow again.

Since

the movie is so much about music, how vital was it to get legendary

Cuban pianist Bebo Valdés involved in the film?

Since

the movie is so much about music, how vital was it to get legendary

Cuban pianist Bebo Valdés involved in the film?

That was an

idea that came to us at the beginning of the movie. When we decided

that we are going to make our love story and that we wanted a lot of

music in it, so let’s do a story about two musicians. She can be a

singer. He can be a musician. Then we said, “What if he’s a

pianist? Then we can have Bebo playing for him.” That was a

crucial moment for the movie, because then, we started to put

everything together from that moment on. It was a great privilege.

Bebo was already very old at that time. He has just retired,

stopped having concerts and performing in public. Chico & Rita

was his last work, his last professional achievement.

It

was a gift for us. It was a privilege. That’s why we dedicated the

movie to him. He’s now 93. He loved the movie. When he saw the

movie finished, it was the only time in my life I saw him crying

with tears like a little boy. For me, it was a moment I will never

forget in my life. He said to me a beautiful thing. I had

never thought that way. He told me, “You know, Fernando, I’m not

going to be here. Because of this movie, people will be still

listening to my music.” I love that he takes the movie this way.

It was a very emotional, strong moment for us.

Were Chico &

Rita based on specific musicians, or were they more loosely based on

lots of different people?

Yeah, we

picked from a lot of different things. When you are writing a

book or writing any fiction work, you pick things from your own

life, from stories that you heard, stories that you’ve read or

stories that you know through someone else. I’ve been in the

musical ambience for many years. I’m friends with lots of musicians

and lots of Cuban people – not only musicians, but also actors and

writers. So you have a whole biblioteca [Spanish for

library] of personal experience. It’s just to choose the right ones

and invent the right ones that you need for the story. It’s always

like that, fiction grows from reality.

I believe that

Chico & Rita

is your first

animated film.

It is.

How

was making it different than making a live-action film?

How

was making it different than making a live-action film?

It’s the same,

but it’s completely different. The most important thing is that you

need to have the whole movie shot by shot in your head before

actually making it. That’s a big thing. That makes a really,

really big difference. When you do live action movies, you have to

think out a lot of things before, but you can let many, many things

happen in the process. Say, for the actors, there is some room for

improvisations from the moment of inspiration. But here, you need

all this inspiration before the movie gets done. (chuckles)

Even though

the film is animated, you did spend some time in Havana filming.

What was that experience like and how did it add to the feel of the

film?

We work a lot

with Cuban actors and Cuban musicians and also doing research,

photographs, everything to prepare the movie. So, we did a lot of

work there before.

Animated films

tend to be aimed towards children. Why do you think that the art

form is not used more often for adult stories like

Chico & Rita?

This is a

process that started in the comic medium with graphic novels. When

Art Spiegelman won the Pulitzer Prize for his book Maus, he

demonstrated to the world that comics can be adult, not just

superficial entertainment for children or for childish adults. He

and people like Robert Crumb and some other artists demonstrate that

was a medium that can tell complex stories. I think that after

graphic novels, now is the time for animation movies. That’s why a

movie like Chico & Rita [can be made] or other movies like

Waking Life [by Richard Linklater] or Persepolis [by

Marjane Satrapi] or Waltz with Bashir [by Ari Folman] and

now… the other day we were in New York for the opening of Chico &

Rita and we were with Jonathan Demme and he’s working on Zeitoun,

David Eggers’ book, to make it into animation. So I think animation

is growing.

One

of the great things about

Chico & Rita

is – and nothing against computer animation – but it is a reminder

of how vivid and powerful traditional animation can be on screen.

Why do you feel that hand-drawn films are so rare anymore?

One

of the great things about

Chico & Rita

is – and nothing against computer animation – but it is a reminder

of how vivid and powerful traditional animation can be on screen.

Why do you feel that hand-drawn films are so rare anymore?

We are in a

very important technological moment. A lot of things are happening

that are wonderful, but at the same time, we wanted to keep that

human hand in Chico & Rita. We didn’t want it to be an

animation technological thing. We wanted to keep the human factor

all along the program. It was a Mariscol project to me. To keep a

Mariscol style, Mariscol lines and colors and drawing, I didn’t want

it to lose that. It would be different if I was doing a movie with

Pixar. I know Pixar has its own style. So, I will work for Pixar’s

style. But here, I was working with Mariscol, so what I wanted in

the movie was to have as much Mariscol style as possibie.

How did you

find out about your Oscar nomination? What was that like?

(laughs)

That was a lot of fun. Very nice surprise for us. We are very

happy with it. Already to be nominated to me is like an award.

Generally

these days the animated film Oscar nominees are sort of made up of

high profile computer animated blockbusters. How exciting is it for

you as a filmmaker that two smaller, traditionally animated,

foreign-language titles like yours and

A Cat in Paris

were recognized, particularly over high profile films like, for

example,

The Adventures

of Tin Tin?

Well that

proves that the Academy is very open. The same way they have the

Iranian movie A Separation nominated for Best Screenplay. I

think that’s great, because it’s really one of the best

screenplays. For me, it’s the best movie of the year. (laughs)

So, I really appreciate that the Academy has an eye and an ear for

this kind of movie, too. It’s very interesting and for us, we are

very grateful for it.

You

had previously won an Oscar for

Belle Époque.

Does that make another nomination easier to handle? Are you ready

with your speech just in case?

You

had previously won an Oscar for

Belle Époque.

Does that make another nomination easier to handle? Are you ready

with your speech just in case?

Not yet. Not

yet. But it’s true, that having been through it before makes you be

more comfortable at it. Also, being eighteen years older made

things just a bit different. (laughs)

What are your

plans for the Oscar weekend?

Well, there is

going to be a viewing party with all the friends and family here in

LA. [There will also be] another party in my home in Madrid. And

another one in Mariscol’s studio in Barcelona. So, I hope now

through Skype and that, the three parties, we will get in touch one

with each other, because there’s going to be a lot of people in

these three towns. (laughs hard)

What do you

have planned next?

I just

finished my new movie. It’s a live-action movie, my first movie in

French. It’s called The Artist and the Model [El artista y la

modelo]. It’s with Jean Rochefort, Claudia Cardinale and a

young Spanish actress, Aida Folch.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.