A new

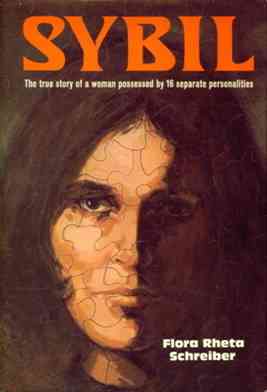

book reveals that the sensational multiple-personality story was

just that ó a story.

In 1973, Flora Rheta Schreiber wrote about the treatment of Sybil

Dorsett (a pseudonym for Shirley Ardell Mason) for

multiple-personality disorder (sixteen separate personalities in

all!). The disturbing book touched a nerve in the culture and raised

questions about the nature of self. Meanwhile, that same year,

another girl had personality troubles of her own in The Exorcist.

The psychotherapy industry salivated, taking furious notes. The

Exorcist went on to earn its own lore, and Sybil helped

to create a new psychiatric diagnosis (itís known today as

dissociative-identity disorder). Since then, the Sybil story

has nurtured a cult of obsessed fans.

The book sold six million copies. An NBC miniseries, starring Sally

Field and loosely based on the book, was seen by one-fifth of the

country when it first aired in 1976.

However, Sybil was not all she seemed to be. In her new book,

Sybil Exposed [Free Press], investigative writer Debbie Nathan

sheds light on how the famous multiple personality case was

fabricated, exaggerated and bent to the will of the bookís author,

the patientís therapist [Dr. Cornelia Wilbur] and even the patient

herself. This trio of ambitious people rigged and concocted an

incredible fiction that reads like fact.

Here, Debbie Nathan gives us a peek into what went down and what

went wrong.

Why

did

Sybil cause such a ripple in the popular culture?

Why

did

Sybil cause such a ripple in the popular culture?

One reason was the sense of power in women, that they could overcome

any kind of adversity, that they can make use of untapped talents

that they didnít even know they had. That was a powerful thing. It

also made people much more aware of child abuse and the secrets of

family troubles. On the other hand, it also gave women the feeling

that the only way that they could express themselves was through the

splitting of their personalities into a lot of different parts. So

it had good and bad effects on the culture, but it was extremely

powerful. Emotionally, it was an incredible read back then, but itís

only an incredible read if itís true.

Multiple personalities were nothing new when

Sybil debuted, but it seemed new.

Multiple personalities were always present in western culture

ó the idea of being possessed, these different people whom you

canít control, as beings inside you. Itís a very central attitude in

Christianity, particularly.

So the story was exaggerated and shaped so that it could be more

sensational. Thatís nothing new, is it?

It happens now in journalism. We see all these scandals with

memoirs. And in journalism, we have all these young reporters who

are exaggerating like crazy. Sybil might have been one of the

first examples of that. [Author Flora Rheta Schreiber] did pretty

solid work, but in her research, she couldnít get what she wanted

out of it. It was just too late. She already had the fortune from

the advance, and she had sugarplum fantasies of fame. It was a

really sexy idea. Of course, the therapist had a lot of ambition

because of her upbringing. Her father was a famous chemist and she

had started out as a chemist under his thumb. But she ultimately did

not become a chemist; she became a psychiatrist and she was always

looking for the next big thing in psychiatry. This was definitely

the next big thing. I mean, how are you going to walk away from that

once you believe in it? Nothing was going to contradict her

ambitions.

Sybil herself, while troubled, didnít suffer from

multiple-personality disorder.

The patient herself bent every which way the wind blew. She was a

very suggestible person and she depended on the love and support of

these women, particularly the psychiatrist. I imagine she had some

of her own ambitions. She was willing to be manipulated at the same

time that she was manipulating them. It was a very interesting

dynamic.

In

the book and miniseries, Sybil had a monster mother from hell, but

it wasnít quite like that in real life. But did child abuse play a

role in the real Sybilís troubles?

In

the book and miniseries, Sybil had a monster mother from hell, but

it wasnít quite like that in real life. But did child abuse play a

role in the real Sybilís troubles?

Nobody is saying that terrible things donít happen to kids. My book

doesnít suggest that. What it does suggest is that itís pretty hard

for things to happen to kids on a large scale without anybody

noticing and without kids remembering what happened to them. Her

mother wasnít a schizophrenic. She was probably depressed. She had a

clinical diagnosis from about 1912, what today would be known as

depression. She would probably go into deep depression occasionally.

For a little tiny child, to be around a depressed mother, itís

probably a very bad experience. It creates detachment problems. She

grew up in this very repressive religious background and she was an

artistic kid. I donít think it was a happy experience growing up

with that mom, but the mom clearly wasnít a monster. There is no

evidence of that at all.

Did all three women get what they wanted?

I think the psychoanalyst did. What she wanted was fame and she got

fame. But I donít think the other two did so well. I think in some

ways, Sybilís story was a curse for the journalist. She took the

straw and she spun it into gold. Then, the next time around, she was

expected to write a bestseller that would do equally well. She

couldnít really do that. She spent a couple of years spinning her

wheels. She gets a huge advance to write about anything she wants,

but she canít figure out whatís going to sell. Her need to write a

really sensational bestseller made her see herself as a lay

psychoanalyst. Shirley Mason herself was ruined by this. She was a

teacher doing well. She lived on the border of West Virginia and

Ohio and she had a good job that she was very happy with. She had to

give all that up because of the fear of people learning who she was.

She ended up in the shadow of the psychoanalyst for the rest of her

life. She was like a little mouse. She ended up dying alone.

What lessons should we learn from the

Sybil hoax?

The story is so bizarre that it is more sexy than

enlightening. Yet itís telling us how to think about ourselves,

particularly for women. When you read stories that are so bizarre

that they are not like you or anyone else you know, you should step

back and ask, ďwhatís going on here?Ē Second opinions should be

encouraged. Fortunately, we live in an age now where we are

critical; we go on the Internet, we look up information. We have all

these places now where we can go and check what we are being told.

We need to be constantly critical of medicine.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.