PopEntertainment.com > Feature Interviews

- Authors > Feature Interviews F to J >

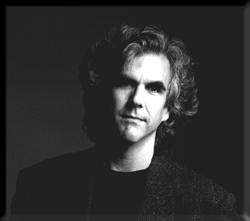

Stephen Fried

Stephen Fried

Stephen Fried

Gia and

the High Cost of Beauty

by

Ronald Sklar

Copyright ©2006 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

September 18, 2006.

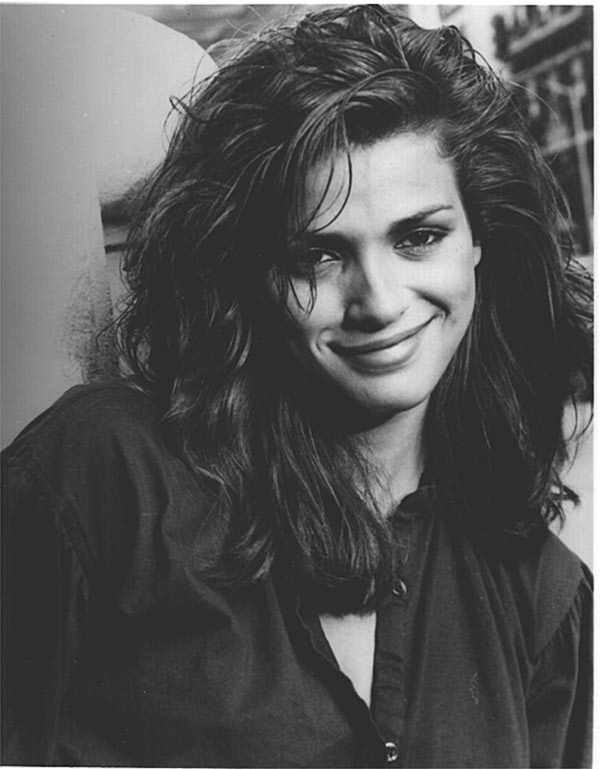

Twenty years ago, the fashion world's first

supermodel, Gia Carangi, died of complications from AIDS. It was a shock

that made the world reel, at a time when the human race was just barely

coming to grips with the reality of the illness (seemingly invincible

actor Rock Hudson died a year later). What was even more frightening: Gia

was one of the first women in America to die of the disease.

By the mid-eighties, Gia's spectacular and

as-yet-unparalleled modeling career was long over. She began to

self-destruct early on, mostly from drugs and partly from a misguided

search for love (she was an avowed lesbian). However, when she first made

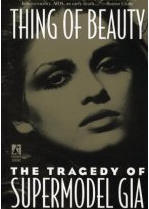

the scene in 1978, she was something to behold, a "thing of beauty," as

the title of Stephen Fried's classic biography ironically suggests (Thing

of Beauty: The Tragedy of Supermodel Gia, Pocket Books, 1993).

In the shallow, cut-throat business of fashion

modeling, Gia was at first a golden child. She was beloved and cared for

(while she was on top, that is). Very few of the fashionistas (as

Fried famously termed those in and around the fashion business) kept up

with Gia as she began and eventually completed her tragic fall. The

business moved on quickly – succeeding supermodel Cindy Crawford was first

known as Baby Gia.

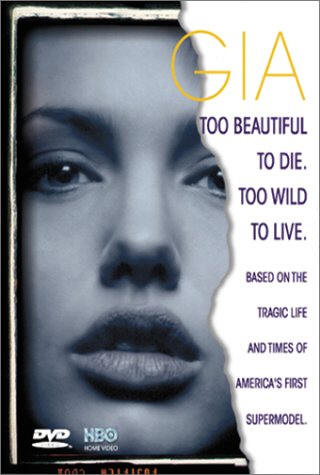

The publication of Fried's book in the 1990s – and a

subsequent HBO film on her life starring Angelina Jolie – helped fuel the

growing interest in this stunning and sad woman.

To this day, Gia's rags-to-riches-to-rags story

continues to fascinate, from her humble, working-class beginnings in

Northeast Philadelphia to her scaling of the heights on the runways and in

the photography studios of New York, Milan and Paris.

On the twentieth anniversary year of Gia's death,

investigative journalist Stephen Fried reflects on the life and legacy of

this beautiful, heartbreaking subject – we learn what he has learned, and

we are reminded of what her story really means.

Gia was

more than just a pretty face. She was a very complex person with as much

ambiguity as charm and intelligence. Are you able to describe her to us?

Gia was

more than just a pretty face. She was a very complex person with as much

ambiguity as charm and intelligence. Are you able to describe her to us?

I did my best to describe her in the book, seen

through the eyes of the people who knew her. I never met her myself (even

though she lived near me for a time in Philadelphia) and I know from

talking to others that she was different things to different people—not

uncommon for a model, or a woman who didn't live past her mid-20s. I think

those who care about her—and that group grows as people find the book and

the HBO film—will continue to try to describe her. I can still only

provide the raw material which they will process their own way.

Has your

take on Gia changed since you wrote the book over a decade ago?

Not much. I was fascinated by Gia because she

was a product of the broken homes and broken promises of the 60s and

70s—the fact that she was a model, and people might be more interested in

the story of her family, her homosexuality and her battle with

self-destructiveness was just an added bonus. The only thing I probably

see a little differently grows out of the changes in the field of

psychiatry. When I started telling Gia's story, in a magazine article in

the 80s, the importance of biological psychiatry was still being explained

to Americans. The issues about whether Gia's problems were from nature or

nurture got caught up in the debate between psychodynamics and

biological-based mental illness. While Gia had plenty of family

problems—her parents' divorce, her very close but very challenging

relationship with her mom—I suspect both I and her doctors didn't pay

enough attention to her underlying mental illness. If HIV hadn't taken

her, I suspect she would have responded very well to the newer psychiatric

medications and types of therapy. At least, I like to think that.

How did the

idea to write the book come about? How difficult was it to uncover the

truth about her life?

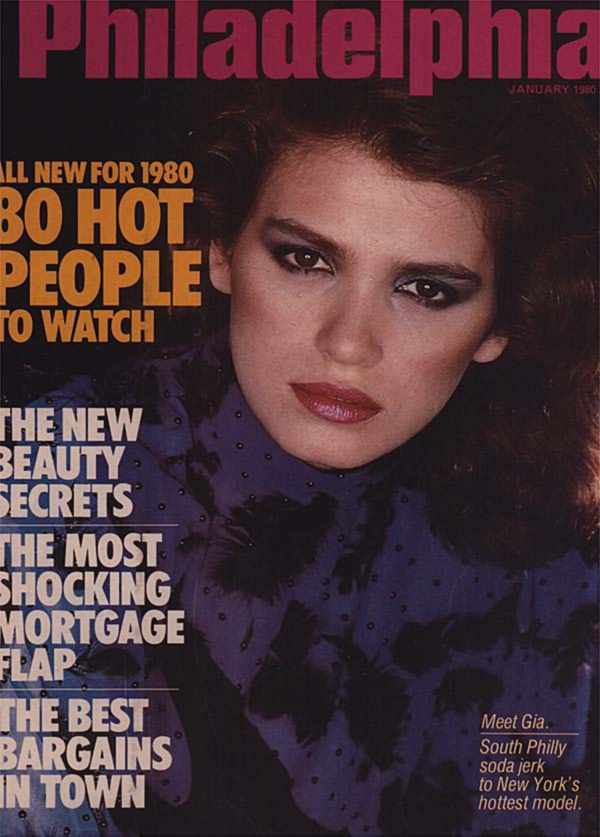

I knew about Gia because she was from

Philadelphia and had been on the cover of

Philadelphia

magazine when I was just out of college—several years before I worked

there. Very few people knew she was dead, and about year after her death

her mother called into a TV talk show about AIDS and told the host, Wally

Kennedy, that Gia was her daughter and she had died of AIDS—as a way of

encouraging Wally to cover the disease more. Wally and I had done some

previous programs together, and he called me and suggested I meet Gia's

mom, that there might be a good story. He was right. I did a long magazine

piece on Gia's life and death and felt when it was done that there was

much more of a story than I had been able to tell even in a 15,000-word

magazine article. So, I did a book proposal and was fortunate to get a

deal to expand the research and the writing into Thing of Beauty.

How was

your experience gathering information and stories from

fashionistas?

How was

your experience gathering information and stories from

fashionistas?

Well, everybody who agreed to speak to me was

great. It took a long time to convince some people—just because they were

nervous about talking about AIDS and wanted to make sure that what I was

doing would be true to Gia's life and her memory—but once they agreed to

see me, they were very forthcoming, very emotional and very moving. Many

of these are people who the public considers to be somehow "shallow"

because they work in fashion. I'd say in all my years of interviewing, I

never spoke to people as deeply as I did about Gia. A lot of the people

who did talk did so because Monique Pillard at Elite, or Francesco

Scavullo, the photographer, told them I was OK. They had been sources for

the original article, and opened a lot of doors. They both loved Gia very

much, and both felt they could have done more to save her; they may have

been too hard on themselves in that regard, but I think that what they

allowed me to do was something that serves as a powerful cautionary tale

for a lot of people. They were brave to trust me. My only regret is the

people who would not talk to me, but who later read the book and wished

they had: especially Gia's close friend Sandy Linter, who was my holy

grail during the research, never did speak to me for the book, but was

very kind and insightful when I met her later on.

Before your

book, Gia was only known among insiders in the modeling and fashion

businesses. That, of course, soon changed. How is Gia perceived by

"civilians" who are not involved in the glamour industries? Do they find

it to be a Cinderella story, a cautionary tale, or both?

I don't think Gia could ever be confused with

Cinderella; she was way too tough for that. I wanted to tell Gia's story

so it would be a cautionary tale, to a lot of different kinds of

people—the least of which were people in fashion. It's a cautionary tale

about family dysfunction, about substance abuse, about homosexuality,

about AIDS, about superficiality, about pain perceived as sexiness. The

book was not meant to be about glamour, and my pleasant surprise is that

most readers see beneath the surface of the fashion business where it is

set.

Your book

caused a sensation when it was first published in the 1990s. What was that

experience like for you? Did you expect the response that the book

received?

I'm not sure it caused a sensation—it got some

attention and some good reviews, and that was certainly pretty great,

especially since it was my first book. It got excerpted in Vanity Fair

which led to me working there for a number of years—so I met my editor

there, Wayne Lawson, through it, and that was significant, he's an amazing

editor. The movie stuff surrounding it was intriguing. Eric Bogosian was

hired to write the screenplay. We spent some time together, which was

great, and remain friendly; the same is true for Robin Swicord, the

screenwriter hired to replace him. And the entertainment lawyer I hired

when HBO ripped off the book, Steve Rohde, remains a friend. The initial

response, actually, isn't really what I remember that much. The more

interesting experience has been that 13 years later, people are still

reading and talking about the book, and Gia is a cultural touchstone, at

least in some cultures. And luckily I'm still writing books—I'm on my

fourth—as is my wife, novelist Diane Ayres, who edited the book.

How did the

people in Gia's life – particularly those who agreed to talk with you --

react to your story?

How did the

people in Gia's life – particularly those who agreed to talk with you --

react to your story?

They all seemed relieved that I had told such

an emotionally difficult story truthfully and without oversensationalizing

it. Only Gia's mom seemed upset, but that was predictable—any mother

reading a book about her dead daughter would be upset, especially if it

deviated from her own view of the story. But, I'll give Kathy credit, she

helped me with the original article and the book, even when she knew that

other people would be telling me harsh things about her. I think she felt

the book was biased against her—that when she told me a story and somebody

else told me another version, that I should have picked hers, or favored

hers. Then when the HBO film came out and portrayed her, so unfairly, as

such a one-dimensional monster, she had a little better appreciation that

I really had attempted to show all sides of a situation that, ultimately,

only Gia could tell us what really happened. I've remained friends, or at

least friendly, with almost everyone who helped with that book. I think

they all feel like they went through a powerful experience with Gia when

she was alive, and another one as they helped me recreate aspects of her

life.

To what do

you owe Gia's fall? Was it her destructive personality, her chaotic family

life or the fast-lane lifestyle of the modeling business?

Gia died of AIDS, and only of AIDS. You can't

forget that. If she hadn't contracted HIV, I'd like to think that all the

things that contributed to her "fall" would later have informed her second

life as a really interesting, powerful grown-up. The disease stole that

chance from her. But, just to be clear, the modeling business didn't kill

Gia and ultimately neither did her family—they just fed her mental

illness, and the cycles of self-destructiveness and self-medication. We

now know what both the modeling business and her family could have done to

help her, but we cannot know if she would have been able to stick with the

treatment necessary to control her illness.

Had Gia

somehow managed to live, where would she be today?

She thought she would be an actress or a

photographer, with a career likely interrupted by kids, which she very

much wanted. She also wanted to be able to be a lesbian and be married,

and I think she'd be delighted to see that is more possible today than it

was in 1986.

What did

you think of Angelina Jolie playing the title role in the HBO film based

on your book? How about Faye Dunaway as Wilhelmina Cooper?

What did

you think of Angelina Jolie playing the title role in the HBO film based

on your book? How about Faye Dunaway as Wilhelmina Cooper?

Just so you're clear: while the HBO film was

clearly based on my book, my book was at the time under option to

Paramount

and is still part of a film in turnaround at

Paramount.

So I had nothing to do with the HBO film except to threaten legal action

when I saw it. That said, I very much wanted

Paramount

to hire Angelina Jolie, who my wife and I had seen in Foxfire, to

play Gia; I think she did very well with the screenplay she had to work

with. Everybody else in the film was OK—it's not Mercedes Reuhl's fault

that the Kathy character was written that way—but nobody in it made me

shiver with recognition of a character I'd spent a lot of time with except

Angelina's portrayal of Gia.

The term

fashionista

has been adopted by the fashion industry and the press. Do you get a

royalty check every time the term is used?

I wish. Although, honestly, it's more than

enough that I invented a word that is now in the Oxford English

Dictionary. It's especially gratifying because my wife, the English major,

always gives me a lot of grief for making up words in my journalism—the

fact that I'm now mentioned in an entry in the OED, one of her bibles, is

very amusing to me. Less so to her. I'm amazed and fascinated that the

word caught on, especially since it has come to mean something fairly

different than the meaning I created it to have. I used it in the book

because there was no other word that described the army of beautifying

people who work in fashion shoots—the models, hair and makeup people, etc.

And it wasn't meant to be pejorative, just descriptive of a group of

people who work much harder than people realize. But, once something gets

out into the culture—a word, a book—you can't control it.

What

project(s) are you currently working on? What can we expect from you in

the near future?

I'm working on my fourth book, but it's the

first biography since Thing of Beauty; a much different kind of

book—a historical biography set in the U.S. in the late 1800s and early

1900s—but in many ways similar because it combines an unforgettable family

who made a real impact on the country, and reporting that attempts to

explore less appreciated aspects of American cultural history. The book is

about legendary hospitality entrepreneur Fred Harvey and the civilizing of

the American West by his restaurants and his Harvey Girls, the country's

first corps of working women. It's due out in a year or so from Bantam.

I've also been doing a monthly column for Ladies Home Journal which

attempts to explain the mind of the modern husband to the magazine's

thirteen million readers; it has been great fun,

and there are now enough of those pieces that there could be a collection.