Like his work

or not, director M. Night Shyamalan employs big ideas and challenges

himself and his viewers with unusual and dark storylines with the

framework to express them. After his incredible success with The

Sixth Sense, Unbreakable and Signs, he was hailed as a

youthful wunderkind with a special skill at fashioning supernatural

thrillers with a twist. Rightly or wrongly, he was saddled with the

idea that his films always had to have a trick ending, a secret to

be revealed, and each film needed to be marketed in the same way.

But then his last couple of films under-performed spectacularly, and

Shyamalan was chastened. So when he landed at Fox with his recent

summer film, The Happening, he was under scrutiny of the

studio.

Although known

as a purveyor of big-budgeted genre pictures, Shyamalan was able to

make The Happening for a relatively modest budget

(approximately $30 million) with a cast of quality actors who don't

necessarily draw in the tentpole audiences. Yet, despite the

pressure to perform, Shyamalan has made one strange film.

One thing this

37-year old Indian-born writer/director understands is that by

basing his films on the realm of fantasy, science fiction, and the

supernatural he draws the mythological aura these genres suggest.

Like Stephen King, Shyamalan tells stories filled with ordinary

middle class people thrown into very bizarre, life-threatening

situations that test their ability to grasp consensus reality and

find solutions.

In this case,

planetary vegetation has somehow reacted to our civilization as an

ecological threat and developed a suicide inducing pheromone that

gets released near large populations. Almost as if the flora has

joined forces to express a warning, certain heavily populated areas

of the East Coast are plagued by a lemming-like wave of gruesome

deaths, starting with an opening sequence weirdly reminiscent of

actual scenes of 9/11 death leaps.

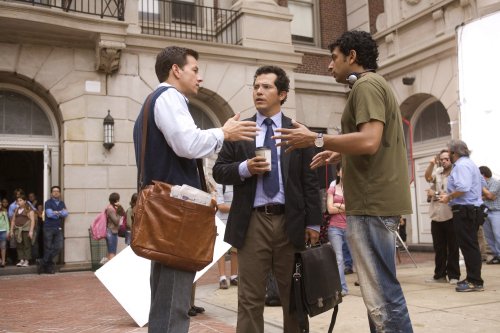

Into this

scenario comes his key cast members Mark Wahlberg (Elliot), John

Leguizamo (Julian), and Zooey Deschanel (Alma) who grapple with

this frightening and unexplainable situation. Once exposed to these

suicides, this trio, and Julian's daughter, try to escape the cities

and survive by isolating themselves from society at large.

Shyamalan

discussed this and more in a recent session before several

journalists.

How

does this storyline reflect your worldview?

How

does this storyline reflect your worldview?

You know, all

these movies, they're all a little bit like therapy about

something that's bothering me or family things. I'm always working

them in, in a journal-like way. But [this film] does represent

things that are on my mind [right now]. I think everybody in our

generation is starting to worry about these types of things.

Certainly in an election year, you think about the future. It's

interesting, this slew of end-of-the-world movies. There's an

anxiety that's in the air, and it sort of mimics the '50s, the same

kinds of anxieties that were about our future. Where are we headed?

Are we going in the right direction? Is it too late to change

course? [I had that] all in the back of my head. I never thought I

was actually all that serious a person. But when I sit down to

write, I guess more adult things come out.

Born in India,

a transplanted South Asian of Hindu descent, your non-western

experiences seems to have influenced you. Plants having a

consciousness is a non-western world view; is that part of the

spiritual side to this film?

Definitely.

It's interesting because of the Native American culture that's all

it's about. My middle name, Night, it's an American Indian name.

That is what I felt so attached to when I was a kid from the

American Indian culture the relationship to nature, and

worshipping the sky, the earth, and the rocks. As a kid, that

relationship felt correct, and it feels correct now as an adult.

It's interesting how in all our religions so little is said about

how we should feel towards nature. It's an interesting thing to kind

of get the hierarchy back in line. We're just one of many living

creatures on the planet. I had this conversation [with some of the

cast]. They asked, "What were you thinking about?" I said, "Jesus."

They said, "What?!"

Your main

protagonist, a science teacher, is discussing limits of rational

thought by the end of the film...

Well, I was

reading the Einstein biography when I was writing the screenplay. I

don't know if you've read it. It's just fantastic. The new one by

Walter Isaacson [Einstein: His Life and Universe (2007)] is a

beautiful, beautiful book. One of the things I was struck by and

when you read the book you may not even see that it's in there, but

I saw it there was that Einstein was this guy [who first] rejected

religion and became atheistic, did his wondrous things in his 20s,

and got really into it. Then in the gaps in science he started

seeing a hand, you know? In his point of view, the hand of God. A

divine kind of "Is there something there?" His life struggle was

finding an overall formula, an overall thing that could define the

design of things, and a belief that it was there. Then he became

very religious. The ultimate man of science became a man of faith.

In a way, when I was writing Elliot [played by Mark Wahlberg], it

affected Elliot. He's just a high school science teacher. He has

plenty of gaps in his knowledge of science. I said, "You're just a

regular science teacher. You're not going to be the hero that

figures out something. It's not like that. But you see in those

gaps

" He honors those things in the gap. That's why it felt like

Mark was the right casting, because obviously he's a man of faith.

Because there are things that we don't know. The lack of need to

define it in the closest category is something inspiring when I see

that in somebody, whether it's Einstein or Elliot's character or

Mark. And so it is a question of science to almost give evidence to

something else.

You

have a math teacher, a science teacher and his psychologist wife a

playing these roles...?

You

have a math teacher, a science teacher and his psychologist wife a

playing these roles...?

The movie's

really about the state of where we are now in the world the

paranoia, how we feel toward strangers, to each other, to other

countries, to everything in the sense that we don't trust anybody. I

was saying that Mrs. Jones is the ultimate version of that character

if she kept on going, she would close off everything and distrust

everybody. So we went that way in talking about her. Really, that's

the part of me that wants to protect myself, and jokes about it, and

tries to undermine it. But it's really a delicate thing for me to

go, "It's better to protect myself. Let me protect myself like

everybody else is protecting themselves." Which is exactly the

opposite of what I tell my kids. I tell them, "Be completely

vulnerable. Take every hit you can because that'll allow you to feel

all those great things that are going to come love, joy,

creativity all that stuff. It will always outweigh the amount of

hits you're going to get. Although you want to protect yourself from

those little hits. Really, the struggle of the movie was her

struggle which is my struggle which is, "Is this person an

appropriate way to be?" Which is the way I am naturally. "Is this an

appropriate way to be, or is this the right way to be?" The struggle

of whether to question it or not.

John's

character is

the guy with the numbers. It always comforts me to

give numbers: "There's a 34% chance that we're going to be okay."

Again, in many ways, they're similar, because he sees beauty in math

as well. So when he tells that story when they're dying in the jeep

he tells that beautiful riddle and says, "If you just double that

penny at the end of the month you'll have over $10 million." It's

amazing, the properties of math. And he tries one last time to teach

this girl in the jeep [who is freaking out], "Isn't math wondrous?

Do you want to hear one more story about it?" Again, they each see

something kind of bigger in their fields. Whereas Alma's the person

deciding whether the world is that way, or if it's really a kind of

crappy place. Literally, it was an agenda. I know this sounds silly,

but I wanted to put the most likable cast that I could possibly put

at the center or the movie. You can get a great actor, but if they

come from a dark place, and then if you put them at the center of

this dark movie, the movie would just become unbearable. [This cast]

all comes from a place they don't know why they do it, but that's

their gift they come from a place of light, all three of them. And

to put those guys, and all the rest of the cast even Betty

Buckley, who chose to play Mrs. Jones trying to have light... And

then it just messes up. A whole cast of actors coming from light was

right at the center. That's why the movie, even though it's so dark,

has such a great light to it. When I wrote the characters, they all

had some aspects of me, of things I was struggling with or thinking

about. Zooey's character is the person that's scared to be

vulnerable. They're all scared to be vulnerable, and use humor to

deflect that feeling of "I don't want to risk myself."

Is it possible

to make a popcorn flick with a serious and important message?

Is it possible

to make a popcorn flick with a serious and important message?

Yeah,

definitely. One of the things that I said to everybody, the cast and

crew, "This is a B-movie here. Let's get ourselves straight here.

This is just a grade B movie. We're making the best B movie that we

can here, that's our job. If the movie has something that sticks

with you, great. But we're not going to put that in front of the

movie. We're going to have a lot of fun. It's a paranoia movie. We

just need to pound away. That's our job." I was really clear about

that. So in that way, it was meant to be entertainment. I think one

reporter asked, "How come you just don't go make a pure popcorn

movie and then go make your art movie? It seems like you want to do

[both in one film]." The problem is that both are my instincts, to

have one [foot] in each place, which sometimes pisses off one group

and sometimes pisses off the other group. My wife says, "Just make

one or the other." I wish I could, but as it ends up, I think about

all these kinds of spiritual things. And I do love cheeseburgers and

I do Seinfeld and I do love Coca-Cola and I do love Michael

Jordan. It's just me. So if I took one side away the side that

really loves to read about philosophy and pretend that side didn't

exist, it would be a lie. And if I pretended I wasn't jumping up and

down watching the Celtics last night, that would be a lie as well.

So it's that balancing act. I keep trying to be honest here.

To

get that mix, this film got an R rating.

I got an R on

two other movies on The Sixth Sense and The Village.

I got an R initially, for the intensity of certain scenes. We were

right on the line, and I could always just pull back and resubmit it

so they go, "Oh, that's much better." All I did was take out some

sound effects. It's always the impact; the emotion was different

than what I actually showed. But this one, with the screenplay I

wrote, there was just no way to do it any other way. One of the

movies I was thinking about was Pan's Labyrinth. I was

thinking about it a lot when I made the decision, because I didn't

want to make it as an agenda. You want to make an organic decision

about what does the material want to do. And when I thought about

Pan's Labyrinth which had visceral moments of violence

juxtaposed against the softer things that are going on against the

canvas it gave it authority and some teeth. For me, a PG-13

version of Pan's Labyrinth wouldn't have had that kind of

impact. It wouldn't have stayed with me the way that movie has

stayed with me. And so it felt like the right balance of things. It

was exciting, and it was disturbingly easy to shoot all those

scenes. I had such a fun time.

What are your

greatest fears in real life?

I've changed

my thinking, and my analysis of fear has come down to the factor of

being alone. It's all based on versions of that. Take random things

that you're scared of

"I'm scared to fly" or you're scared of the

new job that you have. It's all related to the feeling of "I'm going

to have emotions, and no one else will have those emotions. I'll be

alone in some manner." So if you're scared of flying but if you talk

to the pilot or talk to somebody else, you don't feel as scared.

It's the human connection. You're not alone anymore, you have

commonality. And I've said that art, I believe, is the ability to

convey that we're not alone. That's the power of art. It's always

been in our genetics, since we were cave people. Fear protects us

"Don't go down that road, you'll be alone. We don't know what's down

that road. You'll be alone. Being alone is not good. Together we're

safer." And the person that didn't have that [reaction], didn't

survive, right? Now it's flipped on us and become a limiting factor.

We're scared to put our kids in the backyard now because our

neighbors might do something. But our neighbors are wonderful

people; the assumption is wrong. It's the same that it was when I

was a kid running around on a bike. We're so much more scared now,

but nothing has changed. Nothing has changed, except for fear. And

the fear builds on itself, because we get more and more isolated

like Mrs. Jones, until your fear has been realized you're all

alone.