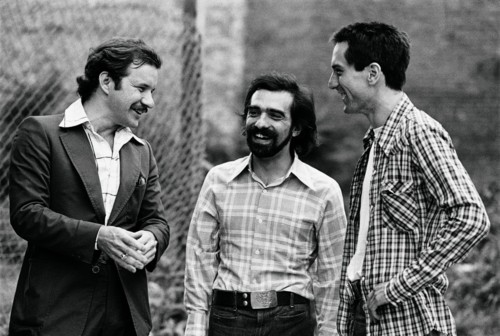

When directors-screenwriters Paul Schrader and Martin Scorsese came

to the Director's Guild Theater in Manhattan recently to discuss

their ride with the groundbreaking film, Taxi Driver, it was

an incredible moment in cinematic history. Their story of how this

film took form and made its mark became even more profound when its

unselfconscious creation was explained.

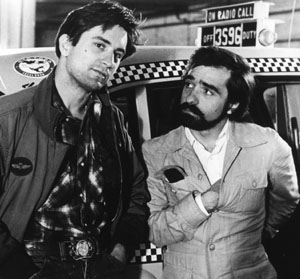

Set in New York City soon after the Vietnam War ended, this film

directed by Scorsese and written by Schrader, starred Robert De Niro

as Travis Bickle and featured Jodie Foster as a child prostitute,

Harvey Keitel as her pimp, and Cybill Shepherd as Bickle’s psychotic

obsession.

This psycho-thriller was nominated for four Oscars, including Best

Picture, and won the Palme d'Or at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival.

The American Film Institute ranks it as the 52nd greatest American

film ever on their AFI's 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary

Edition) list. It is considered so "culturally, historically or

aesthetically" significant by the US Library of Congress that it was

selected to be preserved in the National Film Registry in 1994.

Beyond being classic for its unique sidesteps and plot twists, it

also offered a blistering social critique while exploring the

slippery slope of psychopathic behavior. Not bad for a film

born out of dreams and nightmares.

When it got re-issued as by Warner Brothers as a Blu-ray, that

special sneak screening was preceded by a remarkable tête-à-tête

by these two.

Though this dialogue had been consigned to history, it now deserves

a text viewing again.

Paul, you said that the last time you and Marty were at a public

event with

Taxi Driver was at Cannes in 1976.

Paul, you said that the last time you and Marty were at a public

event with

Taxi Driver was at Cannes in 1976.

Paul Schrader: Yeah, I wanted to issue a certain caveat,

because Marty and I have talked about this film over the years. But

the last time we were actually at the same podium together was at

Cannes in '76. In the intervening 35 years, I'm sure that we have

both evolved our own mythology, which may not in fact coincide with

each other, in which case I will defer to his mythology.

The best place to start is where the movie began – with the

script.

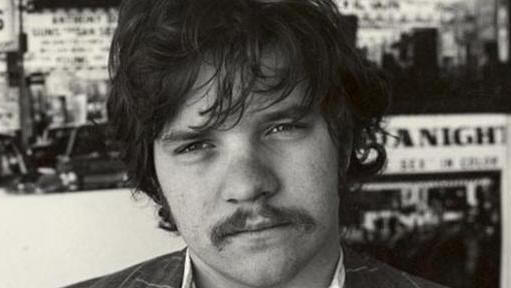

Paul Schrader: This script has since rewritten itself. I was

in a very dark place... sort of in a desperate place, and this

character was starting to take over my life. I felt I had to write

him so I wouldn't become him. I was not a screenwriter at that time,

I was a film critic. But I wrote this as a script rather than as a

novel because I knew scripts. I had been living in my car and

drifting around, and I was in the hospital – at the age of 26. When

I was in the hospital, this metaphor occurred to me of the taxi cab,

this idea of this man in this metal coffin floating through the

sewers of the city, who seems to be in the middle of society but in

fact is desperately alone. In fact, I think it actually worked.

After I wrote the script, I drifted around the country for about six

months and sort of got myself back together and came back to LA, and

then through Brian [De Palma], I ran into Scorsese with the script.

What was it in the script that drew you to it?

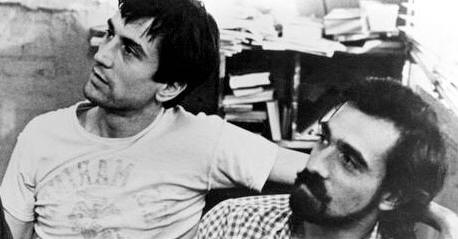

Martin Scorcese: Brian introduced me at that time to Paul. He

took me down to San Diego, I think it was, to meet. But I think he

had given me the script just to read and he said "you should do

this," but I was still editing Mean Streets at the time.

Paul Schrader: I don't know whether I gave it to you or Brian

gave it to you.

Martin Scorcese: I think you gave it, but he told me about it

first.

Paul Schrader: And Brian in fact owns a piece of this film.

Martin Scorcese: He does?

Paul Schrader: Yes. Because I told Julia [Phillips, producer]

in order to move it from Brian to you, I gave him a little piece.

Martin Scorcese: Well, I read it, and the character and the

precision and power of the prose was like poetry. It was so strong,

the dialogue, the scene descriptions, but ultimately it was truthful

and honest and had many feelings that I certainly identified with

later on. I'd done much reading over the years, and a life spent at

the movies in a sense, watching a lot of films. But one of the books

I first read that was a strong impression on me, that I really

wanted to do or to do versions of – or other versions of other works

by this author – is Dostoevsky's Notes from the Underground.

So this is the closest thing that I had come to. I didn't really

think that literally. In other words, it took me a year or two after

making the film to realize it all, I think, but it was just a

visceral reaction to the power of the writing, really, and the

character.

Martin Scorcese: Well, I read it, and the character and the

precision and power of the prose was like poetry. It was so strong,

the dialogue, the scene descriptions, but ultimately it was truthful

and honest and had many feelings that I certainly identified with

later on. I'd done much reading over the years, and a life spent at

the movies in a sense, watching a lot of films. But one of the books

I first read that was a strong impression on me, that I really

wanted to do or to do versions of – or other versions of other works

by this author – is Dostoevsky's Notes from the Underground.

So this is the closest thing that I had come to. I didn't really

think that literally. In other words, it took me a year or two after

making the film to realize it all, I think, but it was just a

visceral reaction to the power of the writing, really, and the

character.

Paul Schrader: I know when I got this idea, I knew there were

two books I wanted to reread. I had recently read Notes from the

Underground, so I reread [it]. These characters were his parents

and his grandparents, and not so much characters from American

movies, but really characters from literature.

Martin Scorcese: I was aware of Camus, The Stranger,

but still for me it was more Russian in a way.

The connection to Pickpocket is also a connection to

Dostoevsky too.

Paul Schrader: I was a film critic and I reviewed this film

Pickpocket [dir. Robert Bresson]. I had never thought that I

would be anything other than a film critic. I saw this movie and I

loved it and I wrote about it repeatedly, and I said "I could make a

movie like that. That's just a guy in his room, then he goes around

and he writes in a diary and he goes back to his room. I could do

that." So when I finally did write a script, what was it about? It's

a guy in a room writing in a diary.

During the actual shooting, if I'm remembering correctly, there

was a garbage strike in New York?

Martin Scorcese: Everything was going on in New York at the

time. It was the hottest summer.

Summer of '75.

Martin Scorcese: '75. It was a nice time, but it was an

extraordinarily hard shoot. They all are, but this had a very short

schedule for us. But there was a garbage strike and apparently

everything was going way downhill. It was the middle of the '70s and

the [federal] government just told [New York City] to go to hell,

"We're not going to bail you out." And [the locations] you had

written about, him driving up and down those areas – Eighth Avenue

was perfect between 42nd and 52nd Street. Perfect. That was our area

where we shot all the time. The sense of violence in the city –

although that's part of my background, in a sense of where I come

from in the city – but the sense of violence in that area in the

summer at night was palpable. You could feel it in the air, and it

was rough at times.

Paul Schrader: There were no locations in this film? No

studio work is there?

Martin Scorcese: At the end there's an abandoned building on

Columbus Avenue.

Looking at the movie now, it's like an index of a lost New York.

So many of the locations are gone.

Looking at the movie now, it's like an index of a lost New York.

So many of the locations are gone.

Paul Schrader: [Writer] Fran Lebowitz spoke to this very

subject in a delightful film that Marty made, with her saying, "We

built Times Square for you and if you don't like it, we'll change

it."

Martin Scorcese: I never thought that would happen. The only

instance I had of that was when we were shooting on Columbus Avenue

and 89th Street in that abandoned building. All those buildings were

being taken down, and there were all these stores that were getting

to be built up, these kind of cooking stores, and a complete store

to buy ribbons. We shot 42nd Street. I used to go up to 42nd Street

to see films if we could, but we always went up with four or five

young guys. It was a horrible, horrible place. It really was

miserable. It had a lot of character, but it was a miserable place.

Even the night shooting there was very disturbing. In my mind, I

guess you could walk around there now, although I don't particularly

like what it is now. But I must say there's nostalgia for it, unless

you were a good drug addict, or whatever you wanted to do or get,

you could get there.

Paul Schrader: On 42nd Street they would have these phantom

shows at 10 am – did you ever go to any of those? – like a big

Hollywood movie, and they would be showing it at 10 am on 42nd

Street for less. It wouldn't even be advertised.

Did you go to any of those shows?

Paul Schrader: Oh, yeah.

Martin Scorcese: Did you go alone?

Paul Schrader: At 10 o'clock in the morning I did.

One piece of casting in the movie is Leonard Harris as the

presidential candidate.

Martin Scorcese: He was a TV anchorman, I believe, and

commentator. Leonard had written a book called Masada Plan,

and he seemed really right. Many people were suggested, but Leonard

turned out to be really perfect for us. We interviewed a lot of

people, and did readings with a number [of them]. One night we met

[former New York mayor] John Lindsay too.

How did Robert De Niro find his way into the part?

How did Robert De Niro find his way into the part?

Martin Scorcese: We didn't have to say much to talk about it,

but there was a lot of rehearsal.

Paul Schrader: This is my take on it. I don't think we really

talked that much about his character. I talked a little bit with

Bobby, but not that much. I don't think you talked that much. I

think all three of us knew exactly who this character was.

Martin Scorcese: Yeah, exactly.

Paul Schrader: We were wired into this kid. And one of the

reasons I suspect the film has an ongoing resonance is because of

the serendipity of three young men in a very similar place coming

together at the right time.

Martin Scorcese: Literally, it was unsaid. And even the scene

I did in the cab with Bob, I always talk about the fact that really

the whole picture is about how he holds his head and his body

straight. But we did rehearsals for like two or three weeks in a

hotel. I don't think there was any major rewriting of any kind. The

reverse angle on him, my sort of point of view, it was pretty much

everything. Keep it lean.

Paul Schrader: I went out to visit him on the set of

[Bernardo Bertolucci's 1900]. We were both in Italy at the

time, and he wanted me to read the script into a tape recorder. I

don't know why. But also at one point in the film he gave me a call

– I was back in Los Angeles working on another film – and he said

"We're doing this scene tomorrow and do you think Travis would say

this?" That was the last time he ever made that call, and I said

"Bob, I'm in Los Angeles, I'm working on another film, you're in New

York, you're wearing my boots, you're working with Marty, you're

living the life. If you think he will say this, he will say this."

How did you have the idea for Bernard Herrmann to do the score?

Martin Scorcese: For me the films that I admire greatly have

wonderful scores and it comes from the Hollywood tradition of film

scoring – also foreign films. But with Mean Streets that type

of filmmaking wasn't for me. I thought the score of the picture had

to be created from bits and pieces that I heard in my head, that I

lived with, etc. In Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore a similar

thing was done. But here, with Travis, he just never listened to

music in a way I don't feel.

Paul Schrader: That decision of yours is one that caught me

most by surprise, and I think it's probably really part of the

genius of this film. I had assumed because of Mean Streets it

would all be needle drops, because you were a needle drop kind of

guy. Then when I heard Bernard Hermann was going to do it, I didn't

know quite what to think of it. But history has proved it to be a

truly inspired decision.

Martin Scorcese: He's the only one that could have taken it.

It was the themes from North by Northwest, Vertigo, and even

The Devil and Daniel Webster, pictures like that. Whenever I

thought of a film over those years in the '60s and '70s and I'd go

back and look at it, I'd say "Well the film wasn't as good, but it

was the music." Even like pictures that he made at Fox – [such as]

White Witch Doctor with Robert Mitchum and Susan Hayward – I

think the music is great. The film's not very good, but the music

is. In any event, this is the move and tone, the cab just taking us

down to levels of the Inferno, taking us all the way.

Paul Schrader: Was he surprised when you asked him?

Martin Scorcese: Yes. I met him through Dutch filmmakers in

Amsterdam. They had worked with him on a picture, and I called him

on the phone and I said "I really admire your work, sir. I'd love

you to do the score for my new picture, it's called Taxi Driver,"

and he said "I don't do pictures about cabbies." So we sent him a

script and we met him in London. He especially loved the character

and he loved that [Travis] ate cornflakes with the brandy, and that

did it. "See, I'm all brass," he said, "All brass. All strength."

And when that first cue came up, it surprised me.

Paul Schrader: Even though we're involved with it, we can be

objective enough to say that is a real moment. It turned out

wonderfully.

You weren't eating cornflakes with brandy?

You weren't eating cornflakes with brandy?

Paul Schrader: That's Country Priest. The wine and the bread

and all that. The Catholic wine and bread becomes cornflakes and

brandy. It's not that big a jump.

Is it true that Merchant of Four Seasons by Fassbinder was

something else that was on your minds?

Paul Schrader: It was on Marty's mind, color-wise. I know

because he mentioned it to me.

Martin Scorcese: We had a lot of trouble pulling the picture

together. Michael and Julia Phillips really tried, and the

combination of all of us together finally was able to pull it off,

but it was pretty low budget for the time. For a long period of time

I was thinking black and white, but then it would be too

pretentious. Then I really felt we would do a black and white video

even, because we couldn't get the money for it. I remember going to

see the latest video films that were being made. David Hemmings had

actually made some, and the quality wasn't quite really right at

this point. The color was very troublesome to me. Then I said, what

about the desaturated color that I use at the end of the shootout?

Moby Dick was done that way, the film that John Huston

directed. He devised this color scheme with Oswald Morris which

would look like whaling engravings. But Merchant of Four Seasons,

or Fassbinder – they were showing the West German Renaissance

pictures at the Carnegie Hall Cinema, and I saw two of them. One, I

don't remember what it was; and the other was Merchant of Four

Seasons. I don't get a lot of them. It's way over my head – the

Fassbinder stuff, I just don't get. But the thing about Merchant

of Four Seasons [that] had a kind of brutal honesty [was] the

way the camera looked at the characters, at the actors, and not

necessarily the melodramatic scenes. I realized you could do

anything, really. What I meant by that is, as long as you feel

honest about, it it's an honest image. It's like seeing a police

photo, a crime scene photo. There's a certain objectivity to it. How

does a crime scene photographer choose the angle? You know what I'm

saying? Is he like, "This will be nice."? No, he's not going to do

that. He's like "Here it is. Life, death, right here." That's it.

That was the impulse that Fassbinder's stuff gave me.

You mentioned the desaturated color in the shootout. For some

reason it keeps coming up as an issue about to what degree it was a

choice and is it something that was imposed on you?

Martin Scorcese: The imposing was to cut the picture for an

R, because we were getting an X. There's a long story. [In] Julia

Phillips' book there's detailed stories about how she handled it, or

Michael, and everyone else. I didn't know what else to do. I did

have to cut some of the flowing blood sort of thing. Some of those

things, I'm used to it because – I don't want to spoil it for you,

but there's a person there with a pump, and there's a wire, and you

don't realize it. Even the beginning of Goodfellas – we had a

preview where Joe Pesci takes out a knife and stabs Frank Vincent in

the trunk of the car. In the first cut, we had seven stabs and it's

a big kitchen knife. Even then, after the second thrust, people

started to leave, and Thelma [Schoonmaker, editor] tells me, "I

think we have like six more." It's not an excuse, though, because I

did have to trim frames and that sort of thing, especially with the

hand. There's no music over the shootout either, which makes it very

disturbing. And then somehow, some way – lots of trouble, lots of

arguing, lots of fights – I said, "Hey, I have an idea. What if I

tone the color down?" I just grabbed it out of a hat, which was, in

a way, an excuse to do something I always wanted to do. Actually, I

wanted the whole picture to be that way. I think the last time it

was used that way was Reflections in a Golden Eye, but

everybody complained because they came out of the theater and it

said the film is in Technicolor and they said "It's not in color!"

Yes it is! But in any event, it took us some doing, but I liked it a

lot. And also it gave me an extra – serendipity, I guess you say. It

gave it more of a tabloid feel. The whole picture should have looked

that way. Michael Chapman, his photography's extraordinary, but he

liked what we did, too, I think.

Paul Schrader: I should add – because I saw this in Berlin a

month ago – that Marty made the decision to try to restore the film

to the condition it was when it was first projected at the Beacon in

1976, and that included a very tattered logo from Columbia Pictures.

Martin Scorcese: Because Dan Perri and I did the title

sequence and that's when we got the idea to keep it as grainy and

contrast as high as the last sequence of the film. That's why it

came up kind of dirty looking in a way. Gritty, but tabloid feeling.

What were your feelings when you saw the finished product?

Paul Schrader: Marty had a lot of trepidation when he first

showed it to me. I was just bowled over. I had written more kind of

loneliness dialogue and Marty was apologizing and saying "It just

didn't work, it was too long, we had to cut some of it out." I

realized we don't need that dialogue anymore. We have this huge

yellow monster, and every time you see that taxicab you see

loneliness. You don't have to talk about it anymore. We have a

visual metaphor that has supplanted language. That was my impression

when I saw it.

Martin Scorcese: There was a big choice to be made because

the Checkers [cabs] were still around and we always loved those

Checkers – but a big jolly Checker is a happy car. So we were

thinking of the sleek ones going in and out of the city, the smaller

ones, the sedans or whatever they call those things. But at one

point I said, "We'll never get the camera in there. We'll never get

it shot, so let's go with the bigger car." I came up with the idea

of the opening shot and the steam. Some critic had said "Oh, that's

the level of the metaphor in the film." I never thought of that;

it's just Manhattan with the steam. You want to see it as hell, fine

with me.

Looking back at the movie 35 years later, do you have any

reflections on it?

Paul Schrader: I don't look back on it. I try not to and just

keep moving forward. I don't know about you, Marty, but I always see

everything I could have done better. I'm very gratified and humbled

to be lucky enough to be part of a film that somehow continues to

resonate and have a life. That's just luck, serendipity. There's

talent involved, but talent doesn't necessarily have that effect.

But I have no real desire to revisit it.

Martin Scorcese: No desire to see it again either – pretty

much any film I've made, unless there's a nice musical sequence.

Some of the rock films and rock documentaries I've made, I watch

some of them. Also for me, some times are good and some times are

difficult in life. The films are so personal to me, I get so

involved with the whole process and everything during the editing

and all of that, that sometimes it's hard to revisit that personal

time. It has nothing to do with the picture or the reaction to the

film.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.