PopEntertainment.com >

Miscellaneous > Save the Sitcom

Don’t

Let the Sitcom Die

Don’t

Let the Sitcom Die

by

Mark Mussari

Copyright ©

2005 PopEntertainment.com

All rights reserved. Posted: July 19, 2005.

God help the sitcom. By all accounts the once

hugely popular television genre is on its last breath. One

can only hope that reports of the sitcom’s imminent death are premature.

Long regarded as the poor relative of the

revered television drama, the sitcom has lately suffered from a series of

fatal ailments: lack of originality, weak concepts, paper-thin characters,

mindless writing, fleeting network support. Most recent attempts at the

sitcom only leave the viewer wondering: was that supposed to be funny?

In today’s vapid sitcom universe,

three-dimensional complex characters like Archie Bunker and Hawkeye Pierce

have gone the way of pet rocks and word processors. Instead “types” have

replaced the thoughtful characterizations of years gone by. As F. Scott

Fitzgerald warned us: “Begin with a type, and you find you have created

nothing.”

And what a lot of nothing we now have: there is

the fat husband/beautiful wife sitcom, the “those crazy ethnics” sitcom, the

exasperated boy versus quirk y

girl sitcom. Even critically lauded attempts at something purportedly

different—like the painful Arrested Development—are simply not very

funny. Once it was enough to surround Bob Newhart with a cast of zanies

(twice, no less) and let the yucks fly.

y

girl sitcom. Even critically lauded attempts at something purportedly

different—like the painful Arrested Development—are simply not very

funny. Once it was enough to surround Bob Newhart with a cast of zanies

(twice, no less) and let the yucks fly.

The sitcom’s development during the 1960s and

1970s was a movement toward behavioral comedy that focused on situational

conflict played out by a talented ensemble. This phase reached a pinnacle

with the Mary Tyler Moore Show, which taught us that using

accomplished actors (Ed Asner, Cloris Leachman) instead of attractive tyros

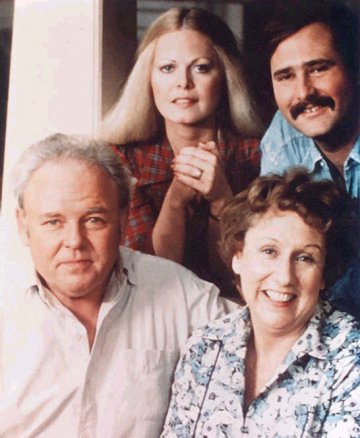

elevates the sitcom. Would a network today give two mature talents such as

All in the Family’s Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton their own

sitcom?

In the 1980s the golden and silver age sitcoms

gave birth to Cheers and The Cosby Show, two notably different

yet equally accomplished examples of the genre. Cheers offered

intelligent comedy in darker tones than a television sitcom set had ever

seen, and Cosby, though refusing to genuflect at any cultural altars,

taught indelible lessons about family and race.

In the 1990s the sitcom took a sharp left turn

with Seinfeld, that rich show about “nothing” that brought a weekly

dose of absurdist comedy into our unsuspecting living rooms. Still, the

basic sitcom skeleton remained in tact: a cast of extremes (all played by

solid comic actors) encircled the pivotal lead (the befuddled Jerry).

Seinfeld’s

greatest achievement was its ability to address the same basic issues as

Mary Tyler Moore (how does a single person make it in the city?) from a

postmodern perspective (she doesn’t) and still be clever and funny.

Seinfeld’s

greatest achievement was its ability to address the same basic issues as

Mary Tyler Moore (how does a single person make it in the city?) from a

postmodern perspective (she doesn’t) and still be clever and funny.

Three other 1990s sitcoms proffered the last

truly admirable efforts in the genre: Frasier dared to be

sophisticated even as television began to eschew making us think. Will

and Grace, especially in its early years, used wit and panache to make

being gay seem both hilarious and irrelevant.

And Everybody Loves Raymond abandoned

anything redolent of “family values” with the most dysfunctional fictional

relatives to grace the small screen. As the hapless Ray warned us in the

first intro: “It’s not about the kids.” Instead, acknowledging the lessons

of All in the Family, Raymond gave us two great actors—Doris

Roberts and Peter Boyle—in supporting roles as disturbing and flawed as a

sitcom gets.

Because it shares reflective qualities with the

culture that gives birth to it, the sitcom’s legacy is too great to

abandon. There is no reason for the genre to die. Lock some writers in a

room and force them to watch “Mary Tyler Moore” for a few months.

Maybe they’ll get it.