Iranian-born

director and artist

Marjane

Satrapi lives in

Paris,

France, and has never lived in post-revolutionary

Persia throughout her adult life. Yet her home

country has shaped and influenced her creative work whether it be

her written and drawn graphic novels or her feature films.

In 2000, an

independent book of bande dessinťe (as comics are called in

French) was released called

Persepolis.

Written and

drawn by Satrapi, it was an eye-opening autobiographical story about

her childhood in Iran, her family's escape (and some cases death),

her move abroad and the demons faced in herself and the world around

her.

Simultaneously

tragic, funny, and enlightening,

Persepolis garnered

acclaim and Satrapi got to direct an animated adaptation in 2007

with artist and co-director

Vincent

Paronnaud.

Because she

gained attention for its unique style and story Ė it won awards at

festivals (including Cannes 2007) and was nominated for an animation

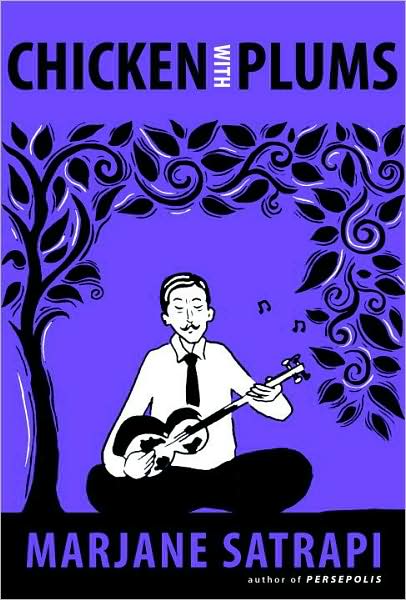

Oscar, Satrapi has gone on to write more

graphic novels, including

Chicken With Plums, a tragic tale based on the

life and death of a relative of Satrapi's.

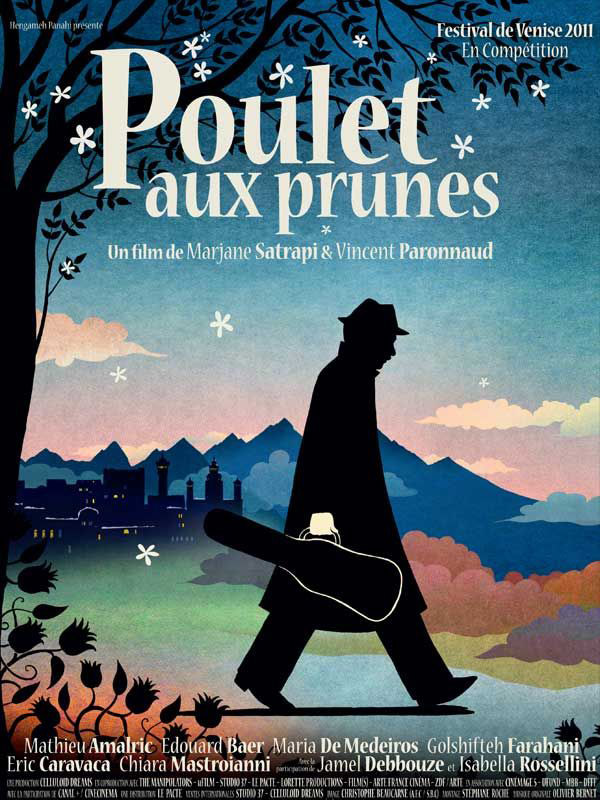

Now the

graphic novel has been transformed into a live action adaptation

starring

Mathieu

Amalric,

Maria de

Medeiros and

Golshifteh

Farahani with Satrapi and Paronnaud in the director

chairs again.

The following

Q&A is drawn from a small roundtable with Satrapi and Paronnaud held

at the

Gramercy

Park Hotel just before the release of the film in

NYC.

With this shift in technologies, how have you grown since the

previous film?

Marjane Satrapi:

Growing up is realizing that the more experiences you achieve, the

more you understand that you donít know so much. This wheel of being

Ė trying to make things before I die Ė itís not like I have 3000

years ahead of me and I can just go on, it's a very simple

calculation. Iíve calculated that I have about 30 years to live and

work, so each project takes me three years, so ten percent of my

time.

So 10 projects

and Iím gone. In the 10th project I have to make the maximum of what

I feel like doing.

I am more

aware of my death, like everybody I guess. But I feel happy. Itís

very sad that we have to die, of course, but there isnít anything we

can do. Itís better to laugh.

What

is it like dealing with an actor compared to telling a story with

illustrations?

What

is it like dealing with an actor compared to telling a story with

illustrations?

Marjane Satrapi:

Well there are different moments you film, but

Mathieu Amalric is a very talented and gifted actor

who expresses lots of things even when heís not doing anything, like

in

The Diving

Bell and the Butterfly. Heís very expressive and

he has this thing in his eyes, this fever. Heís a very gentle person

who is really at the service of the film. It was good for him to be

on the set, it was like a playground.

Heís somebody

whoís actually not scared of playing different roles. He doesnít say

ďIíll look ridiculous, I wonít do that.Ē When an actor believes in a

film, and is committed, and is a great actor like we had the chance

to have, then itís not such a difficult thing to do.

The difference

with animation is that in animation you decide what you want, you

make the movements in front of the animators and they copy you. You

are in control of the project. But when you have actors, they take

the story, and when theyíre great, they take it much further than

what you imagined.

For instance,

when you see

Maria de

Medeiros, who plays his wife,

Faringuisse,

for us she had a range of sentiment and played a nasty woman, but

then we feel compassion for her. She became a bitch at the

beginning, but she becomes beautiful, you love her and you want to

protect her. You want to shake him and say ďLook at this beautiful,

incredible wife! Why donít you want to love her?Ē

Sometimes as a

director, you donít direct and you just become the viewer of your

own film if it goes this way.

Mathieuís eyes are amazing in this film.

Marjane Satrapi:

The eyes are his eyes, but nobody was as close to the book as

Mathieu himself. Every morning I would visit him when he was doing

the makeup and he would say ďMarjane, but the book!Ē And I would

say, ďYes, Mathieu, I know, I wrote the book myself. Forget about

it, itís a work of adaptation, concentrate on your character!Ē

He doesnít

need anyone to make eyes like that, heís an extremely talented actor

and good person.

Is it a challenge going from drawing a graphic novel to

storyboarding a film?

Marjane Satrapi:

We must not forget that the book is a book, and it happens that the

book is my book, but even if it was someone elseís book, weíd do it

the same way. Meaning, it would be an adaptation.

The

storyboards and the comics are not the same; the language is not the

same. With Persepolis we forgot about the book very quickly.

Was there a sense of myth present in the drawing process?

Marjane Satrapi:

Of course, but the only movie maker that knew how to drawÖI think

Fellini drew well. Itís visual art, so itís a plus

if you know how to draw a very simple thing. Like if you want to

show something to your set designer, instead of using 2000 words,

you make one sketch and he understands what youíre talking about.

Itís a plus.

Or maybe since

youíre more visual, you can imagine how everything will look. But

there are plenty of good movie makers that donít know how to draw.

For us, because when we had to re-create a whole world, it was

probably a plus.

But it had an

effect on how we do things, I donít know. Maybe on this movie it

helped because the framing was very classic [in style]. In other

genres of cinema I donít think, because you have to know the

techniques of cinema.

Music also plays a mythic role in this film. What made you feel a

passion for music?

Marjane Satrapi:

Well you have to have some kind of passion, and why not music? You

break your instrument and your heart can be broken, or because your

heart is broken your music is not good. If you paint and you break

your brush, you break your brush every week. You donít break a

Stradivarius every week, you just go out and buy a new brush and

itís no big deal.

Of course the

music plays a big role, and we were lucky to work with a great

musician thatís an old friend of

Vincentís

[Paronnaud,

co-director],

Olivier

Bernet. They had a rock band for a long time and

this boy is extremely talented. They work together and I was

listening, the things you like or donít like.

Since we

prepared the movie, we had an animatic before we finished the film

so Olivier started composing the music to the animatic. So the music

was not completely finished because you finish it on the real

images. But we had the maquetes, so we played the music on the stage

to put the actors in the mood.

What

kind of music did your band play?

What

kind of music did your band play?

Vincent Paronnaud:

We come from the south of

France.

Very underground.

Did you use different musical influences from the North?

Marjane Satrapi:

Pure rock. But they also used in the music some violin and stuff you

donít normally use in rock music.

Smoking has never been so passionately depicted. Are you both

smokers?

Marjane Satrapi:

Yes.

There's a different perception of smoking here in the States.

Marjane Satrapi:

Itís the fashion now to hate smoking. Like all the problems in the

world are solved, no pollution, no shit in water, so now the only

problems people have are smoke and smokers. Itís like if you donít

smoke, then youíre not going to die.

The particles

that stay in your lungs, carbon monoxide, that comes from cars.

Before forbidding smoking we should forbid cars, and then weíll

talk. But both of us are smokers and are proud of it. I donít want

to quit smoking; Iíve been one all my life.

Could you

imagine

Humphrey

Bogart without his cigarette or

Lauren

Bacall without hers? I could go on all day.

Rita

Hayworth without her cigarette?

Jennifer

Aniston and

Zac EfronÖ

Bacall and Aniston, there is no comparison [between them]. Sexually,

from an attraction point of view, everything is not on the same

level.

Smoke is

extremely cinematic. Itís extremely nice to film. Itís also a symbol

of life. One second itís there, the next itís not. It disappears, it

gives you some pleasure, itís a beautiful thing.

But today, if

someone smokes, especially here in the film they have to turn down

the light on the cigarette and in the next few minutes heíll kill a

woman, or a child, or blow up a building. The bad guy is coming, he

lighting up his cigarette.

I had two

grandmothers, both of them smokers, they lived a long time and I had

two uncles that were health freaks and they both died in their early

60ís from cancer.

Even in the

'80s

everyone was smoking.

Bruce Willis

could smoke. Today, everyone is like *gasp*! I donít quite

understand.

I think

smokers are very sexy the smoke as an object is very beautiful to

film and photogenic. It gives you some style. And if you donít have

any style...

The

film is very stylized Ė like the comic. How did you conceptualize

it?

The

film is very stylized Ė like the comic. How did you conceptualize

it?

Marjane Satrapi:

In the film you have many layers. You have one underneath layer with

the story in the

1950ís

with the coup díťtat that happened in

Iran

and the end of democracy, and the name of the lover is

Irane,

which is equivalent to naming a character

America

in an

American

film. Then you have a very realistic story about the people that are

there with no hocus pocus fable things.

Everyone has

their good moments, their bad moments, you donít have a hero, you

have a guy that doesnít like his children at the beginning but then

he does at the end. Everybody, each character has ambivalence, like

it is in life. You donít have great or bad people.

Then you have

another layer of realism, which is the way you remember your

memories. Obviously when you remember, not only does it come in

pieces, not chronological, some pieces are very detailed and

colorful, and some are just an action, plus, this whole reality is

how you remember them, not the reality. Now in all this remembrance,

how to make out of this boring story about a man who wants to die,

an attractive story?

You have all

this work of memory, plus the cinema is a domain where there is no

limit to your imagination, plus the fact that none of us come from

film school, we just go freestyle. All of these were things we loved

and wanted to show in a certain way and it was the result of lots of

work.

The big

challenge was to be able to make it in the way that it would not

look patchwork, the film should be an entity in and of itself.

We had a great

set designer, we watched movies, did documentation, photos, but itís

a synthesis of all of that. The research you do at the beginning,

the result is not always exactly related to that.

What was in casting Golshifteh Farahani who played Irane?

Marjane Satrapi:

Sheís well known in Iran, but she cannot live there anymore, she

lives in France. The reason she was taken isnít because her name was

Irane, it was that when youíre young and you fall in love, you donít

fall in love wondering if sheís intellectual and if youíre going to

have good discussions. When youíre young and fall in love you look

at someone and *gasp* youíre in love. This is the love of youth.

We needed a

girl that when you see her, youíd be like ďwow.Ē And it was this

one. She has something of wild beauty that is difficult to describe,

but she has this innocence in her face and you see her and

everyoneís in awe of her.

We needed

somebody with this face that you donít know where it comes from. She

has made nearly 25 films when she was in Iran, but she played in one

American film with

Leonardo

DiCaprioÖ

Is that why she was banned?

Marjane Satrapi:

She played in that film,

Body

of Lies, and they asked her, ďwhy do you play in

an American movie?Ē She could not work there anymore, and that was

it. If you make a problem, then you go.

Iím not making

Iranian cinema or am part of the Iranian cinematic movement because,

simply, I do not work in Iran. I left Iran when I was very young, I

studied outside. All of my career, my life was outside Iran. Iím

Iranian but Iím French.

If someone

makes a film about

Spartacus

like

Ridley Scott,

it does not make him a

Roman.

This is a French film. If you want to talk about the film makers in

Iran, I donít know any of them personally.

You might be helping themÖ

Marjane Satrapi:

I donít think I can help anything. The government of my country does

not like me. If I say to the government ďplease free these people,"

they will say, ďyou are a woman who is a hooker in our eyes, why

would we listen to you?Ē I am considered an enemy

Any approach I

make to an Iranian film maker will only make their situation worse.

This is why I choose to be far away from them.

What

is the symbolism of the chicken with plums?

Marjane Satrapi:

But

I can tell you exactly. It is a food that comes from the region I

was born in, near the

Caspian Sea.

When men in my family went to eat the plums, they would say they

were eating

Sophia Loren

because they were round and juicy and sweat. Everyone called the

plums the Sophia Loren.

The title is

very important because a film that is a melodrama. If you call it

The Life of Nasser-Ali Khan,

The Musician it becomes too obvious. Itís more fun. But

itís more than that. Thereís a moment in this film, the only

relationship he has with the real world, which is his wife, is

through the food.

Then thereís a

moment in the film when he has a dilemma, he can sit down and eat

and not die, but he decides not to eat. But this is a man that loses

his pleasures one by one. And what is the last pleasure we can lose?

Eating.

You can live

without making love. Youíre miserable, but you survive. But without

eating itís impossible to survive. Also, this is a moment where you

dive into his past. Itís an important moment that looks like

nothing, but itís the turning point.

Do you make chicken with plums?

Marjane Satrapi:

Yes, but I swear to god, I donít lie, I love that food but I didnít

use to make it very often. But after making this film, everybody

says ďmake me chicken with plums so we can see if itís really

tasty.Ē So I have to make chicken with plums for everyone.

You have mentioned your love for the late great Japanese director

Akira Kurosawa and

Rashomon Ė

his seminal film of a crime described by several from very different

perspectives. This film uses a similar narrative strategy. Were you

influenced by other filmmakers?

Marjane Satrapi:

A point of view is only interesting if we all have different point

of views, otherwise we have to make

Superman

and heís very nice and itís not the same kind of movie. To come

back to

Kurosawa,

Iím obsessive. With Kurosawaís

Seven

Samurai, that is the film I have seen the most

in my life. 360 times, at least.

At the age of

10, I became obsessed with this film, and every day I came back from

school I watched it. Every day, without exaggeration. Kurosawa is a

master. I donít need to tell you that.

You wonít do a remake.

Marjane Satrapi:

There are things you canít remake. You canít remake

Citizen Kane,

you donít remake

8Ĺ

or other

Fellini,

itís not possible. Theyíre already very nice.

Do you like other comics Ė ones that influence you?

Marjane Satrapi:

I love American cartoonists. Vincent is much better than me at

talking about comics. What is your favorite?

Vincent Paronnaud:

My comics. Well,

and [Robert]

Crumb.

Marjane Satrapi:[I

love]

Charles

Burns. My next project will probably be, if

everything goes well, an American film.

To be shot here?

Marjane Satrapi:

Iím not going to shoot it here, but the script is American. itís not

my script. Itís a story of a psychopath,

The

Voices. We have to see if people are going to do

it.

It must be fun working for someone else for the first time.

Marjane Satrapi:

Yes, but I told you, I only have 10 projects. I have to try whatever

I can try in this short time.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.