PopEntertainment.com >

Feature Interviews - Actors >

Feature Interviews P to T

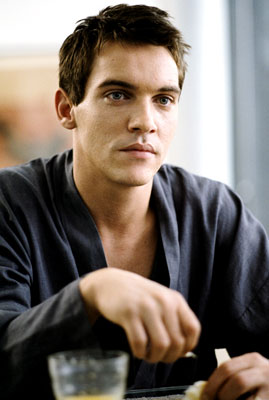

> Jonathan Rhys-Meyers

JONATHAN RHYS-MEYERS

JONATHAN RHYS-MEYERS

PLAYS A

PERFECT MATCH

by Brad Balfour

Copyright ©2005

PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

January 7, 2005.

For a young

actor working with a master director like Woody Allen becomes an honor;

it's an even greater opportunity to perform for him in his first

non-American made feature and a drama no less. In Match Point,

Irish actor Jonathan Rhys-Meyers gets to play both the male lead and a

tragic figure driven by circumstances to perform a drastic act. For Woody

Allen, this film is a risky departure; for Rhys-Meyers – veteran of such

films as Velvet Goldmine and Bend It Like Beckham – it’s

become an enormous responsibility.

Having done other curiously perverse roles playing an outsider – you

get to play an outsider who resolves this film through a decidedly

perverse conclusion – is that something what attracted Woody to you?

I knew it wouldn't be a comedy, because if it was a comedy, I wouldn't

have been cast on it. And I knew essentially that the script had to have

something dark about it, because that's what I lend myself to. Woody, at a

Q&A, said a very poignant thing: you would never have had sympathy for the

character if Jack Nicholson had played him.

So he trusted you with the character?

In casting me as Chris he cast me because all the elements that exist in

Chris exist in Jonathan as well; I don't have to sit down for three hours

in the day and talk about the role. He does place a lot of trust in you to

gauge where the character is at. Of course you can never gauge it properly

because he's got the perspective you don't the onion soup can't taste

itself like the chef can.

And you trusted him in turn to give you feedback?

It's easy to trust Woody; he's a proven authentic genius, so it's a viable

word to use. In trusting you, he gives you a respect well beyond your

years. Rarely do you see a 27 year-old person as a star of a Woody Allen

film – especially someone not from continent of the USA. If he qualifies

you, you feel like better actor on a Woody Allen set.

So what is about you that inspires that trust?

So what is about you that inspires that trust?

I have always had trust in myself as an actor or no one else would trust

me. It would be different if this was my third or fourth film but it's the

28th I've worked on. I am experienced enough to know to the good sense

that a belief in myself is paramount. I may not feel fantastic at 9:30 am

when I am on the set but I know that what I do can end up in the film. So

it's like being a soldier in a war if 90% of the time is spent in waiting

there is 10% of the time spent in extreme terror. You have to have

patience, waiting until the sprinter gun goes off. With a film director

like Woody you do not get many takes to get it right. You have to be

mentally prepared to do the film as intensely as it can be.

What is it about you that suggests a dark side?

I don't know. Woody wrote me a beautiful letter on the inside of an

original copy of Byron's poetical works as a gift, and he says the reason

I cast you is you embody the ultimate Byronic hero – intelligent,

handsome, and slightly tortured.

Would you like to play Byron?

No, not particularly.

Are there characters you'd like to play that reflect that dark poetic

quality?

I'd like to play [the French poet Arthur] Rimbaud, but I'm too old now. I

suppose I could play Rimbaud after he left writing and became a hunter in

Africa, or a slave trader. I think I'd be good to play "the Idiot."

Have you done much Russian theater like Chekhov?

Have you done much Russian theater like Chekhov?

I've never been onstage.

So all your training is as a film and TV actor?

I played

Elvis Presley on TV, which I got a Golden Globe nomination for, and I

played George Amberson in Orson Welles' script of The Magnificent

Ambersons.

Why do you get cast as a musical figure? What is it you understand

about musicians?

Is there's

something rock & roll about Johnny? I don't know. It's funny; I'm doing a

film called August Rush with Kirsten Sheridan in which I play a

young Irish musician. My three brothers and my dad are musicians, which is

really funny. It's in the same vein as to why Woody cast me as Chris

Wilton – there’s something quite beautiful and tortured about musicians.

They always seem to have this deep, unsettling unrest, this inner turmoil.

Match Point is about a guy trying to get control of his life; what do

you think about it?

Well, does he really have a sense of control? First of all, the money's

not his, so there is no control. I don't believe he ever thinks he's gonna

get control by marrying into the family. He wants to be part of a group,

because he spent years as an individual tennis player, being alone, being

competitive. So I think he just wants to be accepted, in many ways.

There's no great intellectual purpose lurking behind this character; it's

a very simple character.

Were class issues a driving force of this film?

You know, I'm not so sure. There has to be something for Chris to aspire

to, so he has to make him working class to aspire to wealth. It wouldn't

have worked if he was wealthy and was aspiring to working class. I think

Woody uses the class system as an aspiration for someone trying to climb

the ladder. So he had to realize his ambition.

And so he had to try to enter a wealthy family.

So, therefore,

he has to come from somewhere with less.

You are typed as a refined person, but you also play against that type

as well.

I get the work that I get, and I try to do the best I can with it. I've

done better than others but, as I've grown older, I've gotten much better

as an actor, and this is one part of myself that I can be proud of: I'm a

much better actor now than I was at eighteen years old. That's rare,

because I remember meeting this casting director and auditioning for him

months and months ago, and he said, "That’s incredible, because most

actors come in, and that's all they have, and they kind of rehash that in

different ways." He said that I've grown, and that's the thing that keeps

me going. I'm an actor in progress.

Is there something to your Irishness that lends itself to an inherent

theatricality?

Is there something to your Irishness that lends itself to an inherent

theatricality?

Of course. It is something about being Irish that lends itself to

something very romantic and theatrical. It's just part of our nature. I

think the Irish are very similar to Norwegians: we have this singsong

accent, this expressive way of talking. It's a shame I don't speak Gaelic,

but in our own natural language, we are even more expressive than we are

in English.

Have you ever played any Jewish characters?

No, and I'm surprised.

You'd be perfect.

I think so too. I remember meeting on this film, when I wanted to play

this Jewish boy who had just managed to escape the Warsaw ghetto along

with 1,100 people, and made his way to Palestine.

The guy wouldn't cast me because he said I looked too much like a gentile.

I found that strange; I really think I could play a Jewish person quite

well.

Looking at the range of people you've worked with, you had every type

of director; Woody Allen is a hands-off type – who was the most hands-on

director?

The most hands-on, I think, was Mira Nair from Vanity Fair.

Was that because she was doing a period piece?

I just think that's how she works, with all her actors and all her pieces.

She would definitely be the most.

And the least?

Definitely Woody is the least. He and Mike Hodges [I'll Sleep When I'm

Dead].

Did you get to know Woody much at all or is he a total mystery?

He's a total mystery. I didn't get to know Woody that much and he didn't

get to know me that much. The longest conversation we had was, like,

fifteen minutes, conversing about a hotel.

Seeing the ending of this film, was it as you expected it to be after

reading the script?

Seeing the ending of this film, was it as you expected it to be after

reading the script?

It was more than I expected, really.

I don't know how I feel about it emotionally.

That's the question it raises in people. How do you really feel about it?

Because a lot of people who've seen it have gone against themselves: I

want him to get away with it. But what does that say about you? It's

moralistically very different, but my personal morals don't get in my way.

I more than likely wouldn't shoot someone and kill him, but that depends

on circumstance. I think everyone is capable of killing somebody. If

someone was to hurt your child, you'd kill them.

Coming from a family of musicians, did you ever regret not becoming a

musician?

No, I don't quite have the talent in that area that my father and brothers

do. And, after doing Velvet Goldmine [he played a bisexual glitter

rock star], there was some interest in me making an album. But, I was a

successful actor, and my brothers were musicians and wanted to become

successful musicians, and so I pretty much let them have their art. But I

don't think I'd ever touch anywhere near as a musician what I can do as an

actor. Just because you're good at one thing, doesn't mean you're good at

all things. And I could never be mediocre at something.

Looking at the roles you've had, you've done a lot of fantasy. Is there

something about you that lends yourself to fantasy? And when I say

fantasy, I don't only mean sci-fi fantasy.

No, I don't believe I'm fantastical. I don't believe I'm all that

fantastic either. But I can lend myself to a kind of ethereal, possibly

mythic, kind of quality. But basically, I try to do the best roles

possible. It's from other people's perspective whether I'm fantastical or

mythical or what.

Having done Velvet Goldmine – which stirred a certain kind of

cult – what do you think about that? I have certain problems with it

myself, especially its depiction of the period. Is that long in your past

or was it something special for you?

Having done Velvet Goldmine – which stirred a certain kind of

cult – what do you think about that? I have certain problems with it

myself, especially its depiction of the period. Is that long in your past

or was it something special for you?

Yeah, I still have issues with Velvet Goldmine myself. But Todd

made it clear when he made it that it's not everyman's 1970s glam walk;

this was basically from a dream he had about how it would be. So it had a

dreamlike quality, just like Citizen Kane had a dreamlike quality.

That's not necessarily how it was that time either. For myself, even

though I played Velvet Goldmine comfortably, I became very

uncomfortable with the stigma that I got. An ambiguous bisexual rock star

came so naturally to me that, in perspective of getting other films,

people think that's what you are. That's really fucking dumb, because I'm

an actor playing a role. But for some people, they really believe this

element of me.

You're working with one of my fave directors who's never been mediocre

– Nicholas Roeg. That's an interesting connection since you played a David

Bowie-like figure and he made The Man Who Fell to Earth.

The film I'm doing with Roeg is an interesting, beautiful, fantastical

ghost story. And it's funny, because Nicholas Roeg's son was one of the

runners in Woody Allen's film. That was an interesting tie-in. But I still

think Nicholas Roeg has made the greatest horror film of all time in

Don't Look Now. It just can't be matched for its sense of cinematic

foreboding. It brought to life a city that was extraordinarily terrifying

in a psychologically terrifying kind of way. I don't think anybody has

made a film that puts so much atmospheric fear, and I think it really

stands above all. I believe The Exorcist is a great horror film,

but I think Don't Look Now surpasses almost anything.