Copyright ©2008 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

March 1, 2008.

Since he was a mere twenty-four, writer Richard Price has been

greatly admired for his amazing ear for dialogue, his seemingly seamless

writing style and his compelling urban plots.

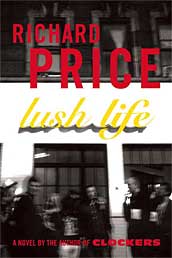

His new novel, Lush Life (Farar, Strauss and Giroux), about

worlds colliding on New York's contemporary Lower East Side, is just the

right Price: a living and breathing thing in your hands. It's not often that

a new Richard Price novel is born, and when you have one, you really have

something there.

This new one, like all of Price's priceless novels (Clockers,

Freedomland, Samaritan, The Wanderers, Ladies' Man, The

Breaks and Bloodbrothers) not only doesn't disappoint, but

feeds your Price addiction for stories that only he can tell. There is so

much truth, humor and just plain real, that anything else you read

afterward feels somewhat artificial and lame.

He is also well-known for his sharp screenplays (The Color of

Money, Sea of Love) and has received an Academy Award in Literature from

the American Academy of Arts and Letters (quick! Name anybody else who

scored this honor.). He also shared an Edgar Award as a co-writer of the

acclaimed HBO series The Wire, which is getting huge buzz of late.

Price graciously sat down with me in his not-too-shabby Manhattan

brownstone (it's a long way from his humble, unlikely beginnings in a Bronx

housing project, but he earned every square foot of it).

We talk about his eagerly anticipated new book, and we discuss this

master writer's writing process. As he is – and always has been, since I

was fourteen-years-old -- my major influence as a writer, I try not to get

too Kathy Bates on him. Just the same, I'll consider our conversation one of

the highlight moments of my writing life.

What

attracted you to writing a book about the Lower East Side?

Just about everybody I know with an immigrant background started

out there a hundred years ago. For about 25 years, I wanted to write about

that. First, I thought about it in a historical mode, but then I realized

that it's the most written-about historical neighborhood in the world.

I would go down there with my kids when they were teenagers. They

knew it better than I did, not because of the history but for what it

became, with all the clubs. They really didn't have any notion of the fact

that they were the fifth generation and that they are now back where

everybody started. So that got me going.

I had no idea what to expect when I went down there. I was still

thinking 'historical.' And then I just saw all the chaos. And I said, 'I

want to write about this now.' And not even now, because now is over.

It's like an institution, the new Lower East Side. The new

Lower East Side is pretty old. But pump it back a decade, when it was first

catching fire.

You said you

contemplated setting something in the past, but ultimately dismissed it.

Have you ever seriously considered a plot set in the past, other than The

Wanderers?

Not really. I'm so obsessive in terms of getting things right, not

that there ever is a real right. That's kind of elusive. It would be too

much work for somebody with my kind of brain. It's very good that I found

what was going on now was more than plenty.

I would say

that perhaps you are not a person who takes an interest in writing

non-fiction.

I've done a lot of journalism, but not recently. It doesn't pay

very well and it's a lot of hard work. I prefer fiction because facts are

facts, and they're facts. In journalism, I did more 'cultural profiles;' it

wasn't like real investigative journalism. It was more like interviewing

people or taking on a social or cultural phenomenon. That's not deep

journalism. But I prefer to be free-range in my imagination and to see

things and to do with them what I want as opposed to be beholden to setting

them forth.

Have you ever

had the urge to write something that is absolutely out of your realm of

understanding?

I'm doing that now. I'm writing a screenplay adaptation of a novel

that's placed in Russia in 1953. It's called Child 44. It's a Ridley

Scott property. I think the book is going to be coming out in a few months.

That's completely out of my experience. And that's pretty much why I took

it.

How was that

for you?

I don't have the same sort of confidence. But you can't be beholden

to writing fiction and feeling like anything is off-limits. It's about

making things up. I just want to know enough to be able to make things up in

a plausible way.

Do you have

any career fears?

Well, there are things I haven't done yet that I probably won't

ever do. It feels like everybody who has ever written a screenplay has

directed a movie at some point. I never have and I probably never will. I

want to write plays. I did a little bit in the seventies. It's not like a

fear; it's a regret. I'll never take on a director role because, in all

honesty, I'm not all that interested in that type of job. I would do it

simply because it's the bigger fish up the chain and that it's the next

logical step. But I feel like I'm a writer, and that's what I do is write.

Are you

computer literate? Do you write on a computer now?

Well, this is the first book I haven't hand written. I've never

typed anything.

Can you make

a living writing books?

Can you make

a living writing books?

I can't personally. I think there are very few fiction writers who

can truly live off fiction without having to either do screenplays or teach

or do something. I don't know that many writers who just sit there and

write books, and the ones who I do are pretty much franchises. They're

best-sellers. It's a done deal before it's even written. There are very few

serious literary writers, I think. It also depends on where you live and how

you live.

You started

out in a Bronx housing project and now here you are. Do you think about it a

lot, or has it become cliché by now in your head?

No, I feel like because of what I write about, I'm supposed to be

living in some walk up or something. I'm not giving it away. I earned it.

But I also feel that the worth is in the work, not in the lifestyle of the

writer. If the work looks earned, it's earned.

Now that you

live near Gramercy Park, do you obsess on which fork to use and things like

that?

No. Listen, the Bronx is where I'm from, and the Bronx is always

where I tend to gravitate back towards, when I'm looking for something to

grab me in terms of writing. That's emotionally and literarily where I'll

always be from. But I don't have to live there. I've been living in

Manhattan all of my adult life.

I know you

are concerned about doing research for your novels. When doing research,

when do you feel like enough is enough?

Here is the thing about research. I read this quote, some writer

being pithy about the nature of writing: researching isn’t writing,

outlining isn't writing, talking about it isn't writing; writing is writing.

And I feel like that's true. A lot of this researching and hanging out or

being in the field or whatever you want to call it is just procrastination.

It's a hell of a lot more fun for me to be out there soaking things up then

me sitting here rearranging the twenty-six letters of the alphabet and

feeling like I'm jumping out of my skin all the time. I'd much rather be out

there. The isolation, the lack of physicality, and the act of writing where

you sit there for a century – I have a hard time with it. I know I have to

get to it. I know I'll invariably spend a lot more time 'out there' than I

really need to.

But it's also

necessary, isn't it? To make your novel the best that it can be?

Nick Pileggi [author of Goodfellas] once said when

researching his book, Casino: when you get to the point when you ask

somebody in the world you're writing about a question, and in your head,

word for word, you say what they're going to say before they say it, then

you know you're wasting your time and you really need to be writing now. I

relate to that very much.

When you

travel around with cops and such, do you feel like you're a pain in the ass

to them?

No, the cop thing gets a lot of play, but I hang out with

everybody. This book is about a homicide on the Lower East Side. The Lower

East Side at this point is six worlds, and the only thing anybody knows

about is the historical, Yiddish boomtown and the new bohemian playground.

The fact of the matter is, there are heavy housing projects, a lot of

tenements, and the realtors haven't gotten to a lot of the tenements yet.

There's still Hispanic, Dominican. There is a huge Chinese immigrant

population, probably the second biggest population down there. Then you have

the new bohemians down there who are sort of playing.

I'm trying to take in that world, and it's like taking in

Byzantium. I'll go with cops because when you go with cops you see things

that you would not normally see. It's sort of like dipping your head below

the surface of the water with a snorkel mask on. It's a whole different

experience than if you're just staring at the water from the sand. Being

with the cops is like putting a snorkel mask on.

One of my main characters is a restaurant manager, so I'll hang out

in these restaurants and I'll go to restaurant managers' meetings. Another

character is a kid in the projects, and here I am again, in the projects.

And I'll go to Community Outreach, guys who work with the Chinese community.

There is a lot of illegal housing situations, no documentation. They're

living cheek and jowl, just like the Jews from a hundred years ago.

Everybody thinks the Lower East Side is this yuppy-buppy-schmuppy

playground, and it is to some extent, and the prices have gone through the

roof, but it's also black and Dominican and Chinese and Orthodox Jewish. And

everybody's talking about this rehabilitation like it's this done deal.

Real estate is violence. It's physical violence, but it's also

uprooting, it's clashing, it's tectonic plates. All that stuff is still

going on. Everybody thinks it's rebirth, but it looks more like afterbirth.

It's chaos down there. It's not a done deal. It's not like this new Disney

Times Square, by any stretch of the imagination.

Are you

exhausted from it, now that you've completed the novel?

If I go down with journalists, it's a little bit like you develop a

dog-and-pony show after a while. But I'm not going to be doing that.

When I'm working on something, and I know that there is going to be

a book at the end of it, there is going to be a lot of anxiety. I'm trying

to get at something, so when I'm down there, there is this edge to me, this

feeling in my stomach. I'm there to get something and I'm not sure what. So

once the book is done, when I go down there now, it's like a relief. It's

like a done deal. It's out. Now I'll go down there, and I'm just like a

human being. I'm not like a maniac on a mission.

When you give

birth to a book, is there like a post-partum depression?

Yeah. Well, it's like people who think of themselves as productive

always think of themselves as sloths. You keep fantasizing that, 'man, it's

going to be so different when this thing is done.'

But you give yourself a one-day grace period, and you're back to

breaking your own balls. It's like 'what have you done for me lately?' It's

like, 'hey, your screenplay's late.' Nobody's saying that to me, but I'm

saying that to me. It's like, if you want to get something done, give it to

a busy person.

What is your

writing schedule like?

It depends what stage of the process I'm in. The time when I plunge

into it first thing in the morning is usually when I'm in a bad place and

I'm in a panic.

Does that

help you write?

Being in a panic? Not productively, but I'll put in a lot of sweat.

Sometimes when you write, and you go off on a dog leg, and you don't want to

admit to yourself that you're going off on a dog leg, so you go further out.

But some part of you knows that you're wasting your time; you're trying to

put a square peg in a round hole and you're wasting all this energy, but you

won't give up.

It's like you're running a marathon and you break your ankle, and

your response to a broken ankle is to run faster and get it over with.

Instead of just saying, 'stop,' I'll spend months going off on a tangent.

There are a couple of hundred pages of this book that I cut.

Do you read

your books after they're published?

I'll read sections. For [public] readings, I'll use sections that I

feel will go over best. It may not be necessarily the best writing, but the

best stuff to listen to, because it has the most dialogue or the most

momentum.

I just picked up Clockers because they just reissued it a

couple of days ago. I'm reading it, and I don't remember writing it. I don't

remember what happened next. On one hand, I'm reading this and I'm going,

'how the hell did I know all this stuff?' On the other hand, I kind of had a

red pen in my hand, thinking, 'cut, cut, cut, cut.'

How about

The Wanderers or Ladies' Man?

I cannot bring myself to read anything from the seventies. Usually,

if you get ten reviews, and one of them is bad, that's the one you remember.

That's the one your mom wrote. The other nine are a blur.

With the early stuff in the seventies, I was in my twenties. I

don't even remember that person, let alone what that person wrote. I was a

kid. It didn't mean that the books didn't have a certain charisma, that

despite the sort of rough writing, it didn't mean it didn't have

electricity. But I can't see it. All I can see is, 'how did I get away with

that? How did people fall for that?'

Do you ever

feel like you've accomplished what you set out to do? Did you "get there?"

I always feel like I've never learned how to write a book, because

what worked the last time might not necessarily apply to this type of story.

And if you try what you did the last time, it might turn out to be a

disaster. Every book has its own way of being written. And you get amnesia.

You forget that for every book there was a lot of anxiety. There were a lot

of revisions. There was a lot of agonizing over 'is this bullshit or not?'

Somehow, the book wound up in the bookstore and it was okay, but

all you wind up remembering is the book in the bookstore. You don't remember

what you were going through yet again. I don't know how old I have to be

before I start remembering that. But I guarantee you that when I write my

next book, I'm going to forget how hard this book was.

Do you ever

feel like time is going to run out before all your ideas are realized?

Oh, yeah. Absolutely, the older you get. That's the problem with

screenwriting. It's lucrative and it pays for a lot of my life, but the

problem is whether something gets made or not is beyond your control. The

older you get, the less patience you have with writing something that might

or might not ever see the light of day. You'll get a lot of dough, much more

dough than you would for writing a really good book, but either two writers

will jump on after you, or it will never get done, or it will get done

despite some cockeyed thing. I want everything to count. I want everything

to be the way I wanted it to be.

The minute you finish a book, you can't ever imagine having an idea

for another one. It's like trying to get pregnant when you are already

pregnant. Let the baby come out.

How about

The Wire? You're getting some rave reviews on that.

I feel like I'm just copping a ride on that. I wrote a number of

episodes and I love it and I love everybody involved. But it's really David

Simon's show. It's based on Clockers, he told me, but he's taken it

way past Clockers. I never got above the streets. He goes all the way

to the state assembly. He really gets the big picture.

I knew him from '92 when Clockers and Homicide were

published at the same time. We both had the same editor. We went out

together on the night of the Rodney King verdict and they were rioting in

Jersey City. We went over to Jersey City to watch the riots.

It was two years into The Wire, which I thought was great

and way beyond me, that he approached me to come on board. I didn't really

want to do it because it was too intimidating. I felt the level, the depth

and the nuance of The Wire was way past my own natural understanding

of things. I thought these guys thought I knew a hell of a lot more than I

did.

I had put everything I had into Clockers, and this was way

beyond Clockers in terms of panoramic and the real politic of the

world. It was like on-the-job training.

Does your

mind have to be wired a certain way to write a screenplay?

You have to be geared for brevity and momentum. It's about speed.

You never want to get flaccid in whatever you're writing. You always want to

have some kind of tension, a taunt quality. But it's imperative in a

screenplay, whereas it's not imperative in a novel.

You can have twenty pages of two people talking on a bench, which

is fine in a novel, as long as what they're talking about is worth reading.

That conversation will be about half a page in a script. It's only so long

that somebody is going to fix a camera on two heads talking without any

other kind of visual shenanigans.

You have such

an amazing ear for dialogue. Do you ever watch something on TV or in film

and say, "oh, brother, this is so phony."

The antithesis of The Wire is Law and Order. Within

an hour, you have crime and punishment. What's good about Law and Order

is that it's plausible, and the good aren't always rewarded and the bad

aren't always punished, which is great, just like real life. It's like you

get a whole meal in one sitting. There's a crime, you go right to the trial,

even though there must be a nine-month gap in there somewhere that they're

not talking about.

But people have these theatrical breakdowns in the box and lawyers

don't object and people are easily tricked into confessing that they're

secret lovers and this and that. At the same time, the show works. But it's

a different type of meal.

The Wire

is like this fifty-course meal, and you get to eat this one piece of sushi

every seven days. On Law and Order, they bring it out on one platter,

and you can just eat until you're done.

But every once in a while on Law and Order, every rich

person is bad; they're snooty and rich, but Law and Order is great.

The Wire, though, is sort of like anti-television. And that's David

Simon's doing. He's more obsessive than I am, because he's trained as a

journalist. He really is obsessed with the pace of how things unfold.

In a way, before the DVD phenomenon when The Wire caught on,

the show shot itself in the foot like that, because things would happen on

Episode Two of Year One that wouldn't pay off until Episode Seven of Year

Two. Who the hell's around to go, 'oh, yeah!'? But he had a vision and he

stuck to it and The Wire's The Wire.

Did you watch The Sopranos?

I love The Sopranos. Some of the episodes were better than

others, but that was a happy medium between Law and Order and The

Wire. Everything was not that hard to get. The characters were

completely vivid and compelling. It was like a slow-motion Godfather.

If you

weren't where you are today, did you ever wonder about where you might be?

Like if I didn't make it as a writer?

Yes.

I think about that. The main character in Lush Life is me if

it didn't happen. A guy who was in his thirties, who came to the Lower East

Side in his early twenties. Like everybody who is there now, he feels like

he is going to live forever and he's going to be an artist and he's going to

make it. And it's cool to be a bartender because I'm really an actor and

it's cool to be a maitre d’ because I'm really a playwright.

Then, all of the sudden, ten years later, the hyphens start to fall

away and he's just a bartender.

There before the grace of God go I. I don't know if I would have

been a bartender, but I probably would have been one of a trillion lawyers.

Click on this link to see what Richard Price had to say

to us in 2004!

Email

us Let us know what you

think.

Features

Return to the features page.

Copyright ©2008 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

March 1, 2008.