When Danish

documentarian Anders

Østergaard took on the challenge to make

Burma VJ, he had no idea how much he would advance the

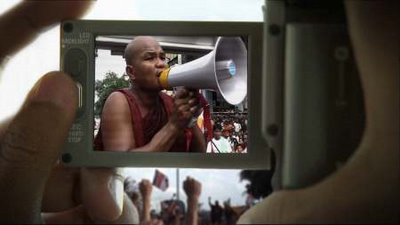

cause of citizen journalism. A collective of 30 anonymous and

underground video journalists (VJs), The Democratic Voice of Burma,

recorded the 100,000+ protestors (including thousands of Buddhist

monks) who took to the streets in 2007 to protest the repressive

junta that has controlled the country for over 40 years.

Since foreign

news crews were barred from Myanmar (as the regime renamed Burma),

the internet was shut down, and domestic reporters were banned

unless employed by the state, they used handycams, or cellphones, to

document these historic and dramatic events; they then smuggled the

footage out of the country. Broadcast worldwide via satellite, these

VJs risked torture and imprisonment to show the brutal clashes with

the military and undercover police - even after they themselves

became targets of the authorities.

Using this

smuggled footage offered for free usage to the international media,

this 40-something filmmaker tells the story of those 2007 protests

and briskly shows how the Burma VJs stopped at nothing to make their

reports with dramatic results. As the director assembled this raw

footage, made on cell phones and other digital devices – and sent

through these clandestine electronic channels – they marked a new

step in freedom of expression and he has stirred a media pot that is

now percolating in other global trouble spots such as Iran. The

protestors there also captured the unvarnished images and reports of

their actions and their government's violent reaction through

digital channels.

Previously

Østergaard had helmed films about pop culture covering such subjects

as the Scandinavian rock band Gasolin' and the Belgian cartoon

classic Tin

Tin. Ironically, with Burma VJ he covered another

pop culture expression – the use of digital technology to create

user-generated content – to document a major political act of

defiance. The results have paid off in various accolades from a 2009

Sundance Grand Jury prize to an Oscar nom for Best Feature Doc.

In fact, this

exclusive interview itself was done through the cutting edge

technology of Skype – so once again the digital domain advances

another journalistic expression.

The human rights abuses in Burma don’t seem to be on the radar like

some other issues. Are you a little surprised that the film has

garnered this support? What do you think made it click?

I think the

uniqueness of the material that these reporters gathered. This

unique access and this very dramatic portrait of an uprising which

they've managed to pass on to the world. I also think some of our

own decisions play a role; our deliberate decision to tell this

story as a suspense story, using all the cinematic tools needed for

that, which I think was a good choice for the film.

How

did you contact the Burmese people? Was there someone who was your

liaison, or was it someone you knew from Denmark? What was the

connection?

How

did you contact the Burmese people? Was there someone who was your

liaison, or was it someone you knew from Denmark? What was the

connection?

It was pretty

straightforward. Once we decided that we wanted to work with this we

got in touch with the Democratic Voice of Burma in Oslo, which is

basically a satellite tv and radio station, and explained our

interest and they were very forthcoming. They needed the attention.

I guess they trusted us, so they sent us to Bangkok to meet twelve

of those reporters who were coming out of training.

Are they paranoid that someone might be an agent of the government?

They're used

to this. I think their biggest worry is that one of their recruits

would be an agent. They deal with this all the time and I'm sure

they made their investigations.

When you made this film what was your hope or your original

expectations for it? Do you think you can change society with it?

Oh absolutely

not. I wasn't too focused on purpose as such. I tend to go so deep

into the storytelling in itself that that's what really drives me

and I don't think too much about the function afterwards. Of course,

I can see from the old pictures that I tried to say that I wanted to

make the Burmese condition tangible, so that you could feel it and

smell it, and I guess that was my ambition, to take it beyond the

abstract interest in some other country and just be there. And that

was what I was totally committed to when I put the film together; I

didn't speculate too much on the aftermath of what might come out of

this politically.

You had so many different people involved; who did you consider your

critical liaison? Who was the one gentleman that you had with you in

the States that was working with you from Burma?

That was very

obvious to me when I met Joshua, because first of all he wasn't

scared. Understandably, most of these guys would be already very

paranoid about what they were doing, so having a foreign film crew

on top of that was just too much, obviously. Joshua had this kind of

fearless attitude to everything, and he also had an intuitive

understanding of how to explain Burma; he's an excellent

communicator. And he has also a mix of qualities that intrigued me.

He was on the one hand this cheeky young guy looking for challenges

and really enjoying his cat and mouse game with the police

sometimes. And on the other hand, kind of a reflective,

philosophical guy, who could also look back and explain the Burmese

condition in a very deep way. So I was just intrigued by his

qualities as a storyteller.

How did you and producer Lise Lense-Møller define your roles? You

obviously have the directing experience, so how did she come in as

producer?

Very much in

the European tradition, I would say, in pretty much keeping hands

off the creative business but making sure to give solid financial

support. For instance, we needed some extra time, and she had the

guts to let that happen even though she was under considerable

economic pressure. So her contribution is mainly securing the

financial circumstances. Creatively, she would be less involved than

some other people.

Were

there moments when you were worried that this wouldn't happen? It

must have been touch-and-go as to whether you had enough stuff that

would make a film, and whether it would look right. Was there a

point where anybody was in danger?

Were

there moments when you were worried that this wouldn't happen? It

must have been touch-and-go as to whether you had enough stuff that

would make a film, and whether it would look right. Was there a

point where anybody was in danger?

Security of

course was a big issue all the time and made some restrictions to

what we could do. We tried to work creatively with that; we tried to

make a virtue out of necessity. How can we work with people when we

can't see their faces? That led us to phone conversations as a

leading tool for the film. Otherwise, just sorting out the chaos;

the material came in a pretty confused way where we wouldn't know

who'd shot what and when, so we had to piece all that together first

before we could start telling the story.

When did you know you had a movie that would work?

I think I was

struck quite early on by the uniqueness of the material, the very

straightforward demonstration of the regime's brutality. But also

the happy moments, the optimism of the early days of the uprising,

when everybody was coming out in the streets, I think they managed

to capture that beautifully, if you consider the circumstances.

These were guys who could barely pay for the bus ticket.

How much information did you decide to put in or not put in? How

much do you reveal or not reveal about the regime and Burma's

history? How much do you assume that people know, understand or are

passionate about?

Much of these

decisions are made by instinct, by the kind of director you are, the

kind of storyteller you are. And as I said before, the number one

thing for me was to make people experience the Burmese condition, to

feel it, to sense it, the whole visceral thing about it. So that led

obviously to me being very, very restrictive about me spending time

on history, on more than just the absolutely necessary information.

Do you hope some day you'll be able to go to Burma without having to

be under scrutiny?

That would be the greatest strength.

Of the many people you've talked to, what are their expectations?

Well

interestingly, in my experience the most optimistic people are the

Burmese, and that's a curious thing. I don't know if it's because of

their Buddhist education, but they seem to be the most patient and

the most convinced that some day that this regime will fall. The

uprising of 2007 was a tragedy, but it was also a reminder of what

people are actually able to do and how they're able to battle their

own fears.

Was there any one person in the film that you consider the key to

getting the film?

Joshua,

meeting Joshua. That was a critical thing, to have somebody who was

able to give his voice to this, and to bridge any cultural gaps and

make it such a smooth and happy collaboration, to me that is a

crucial thing. And also, some of the other guys also had these

qualities actually. So basically the VJs.

Do

you know of anybody that had a chance to speak to Aung San Suu Kyi?

Do

you know of anybody that had a chance to speak to Aung San Suu Kyi?

We'll see;

there are some complications to that.

How did making this film affect you personally?

Well it made

me very busy. Putting a film together like this, first of all is

hard work, and you're so focused on doing it right that you really

don't spend much time feeling a lot of stuff. Just dealing with this

huge responsibility really takes up most of your energy. But of

course, I think what made the biggest impression on me was to watch

the uplifting footage, the hopeful early days, this moves me just as

much as it seems to have moved the audience.

In your one week in Burma what did you see there that you hope

tourists will one day be able to see?

It's a gem;

it's one of the most beautiful countries in the East. Also actually,

ironically, because of the regime things have been preserved in a

way quite different from, for instance, Thailand. It also is in

terrible decay, but the millions of pagodas, the lush green trees of

Rangoon. First of all the people are very mild mannered and gentle

and they're wonderful people.

Have you had an interest in other countries in South East Asia?

Not too much.

I'm not an expert on Burma or on Asia as such. I've done a little

bit of traveling in Indonesia, but nothing that would really put me

in a special position. I came to this as a filmmaker more than

anything else.

I've met a number of the Burma refugees here in the States. It's a

tough struggle. I don't know who has it worse; the Tibetans or them.

It's pretty

bleak for both of these peoples. It's a good fortune that they're

both Buddhists because it helps them a lot, clearly.

One other

really fascinating aspect to the film is your exploitation of the

contemporary technology. Your movie couldn't have existed a few

years ago. When you step back and think about the implications of

that. That must have interesting ramifications in your head.

Sure.

What are your thoughts on this?

Of course a

film is not just about Burma, it's also a celebration of citizen

journalism as such. And telling people that technology is not always

a bad thing; there's a tendency to think that cameras or something

that's going to watch you – that Big Brother is going to watch you.

But it actually can also be Little Brother watching the tyrants,

which I think is a positive note. Basically, I'm every optimistic

about technology, I believe in that kind of thing, I believe in

progress through technology, so I'm happy it's a celebration of that

too.

You obviously have to be emotionally committed when you make a movie

like this but at the same time where do you draw the line as to how

you continue to be committed or not. Obviously, you're going to go

on to do other things after the Oscars, but then you say to

yourself, "Well, do I need to come back to it, to continue to worry

about what's going on in Burma?" Where do you draw the line?

Well I draw it

just around the Oscar, actually. I hope this will be the end of my

story with this at least. Of course personally I will always be

attached to the issue on some level; you don't just quit that. I

made a lot of friends in Burmese circles and so on. But

professionally, I expect this to be the finale of almost one and a

half years of touring with this film.

Of all the people you've met from Sundance on, who's been most

exciting to you?

To be honest I

think what made the greatest impression on me was going to places

like 10 Downing Street and being welcomed. It felt very natural to

be there and to present this film, and that people connected to it

so easily, that was great.

Did you meet President Obama?

No, I never

met Obama. But of course this leaves a huge impression. Otherwise,

what touches me most about this, is when I get, for instance

recently I got a picture from New Delhi, from a open-air screening

on a street corner in New Delhi organized by some local Tibetans. So

they were sitting there in the street watching "Burma VJ" and the

street was packed. Traffic stopped; they were all just sitting there

and totally engulfed with it. They tell me that this has helped to

bring Tibetan and Burmese exiles more together in India and those

are the stories that really touch you.

Are you looking forward to the Oscar parties? Whether you win or

lose you get to go to the Oscar parties.

I guess so. I

don't know what to look forward to but it seems to be pretty

intense.

When you've gone to Oscar events like the nominees' lunch, there's

got to be somebody you're really excited to meet. Give me a fan

moment.

It was a great

moment to say hello to Danny Ellsberg. Even though it's not my

country's history that was nice. Otherwise, I wouldn't say meeting

any specific person, but what I really enjoyed about that lunch was

this kind of collegial atmosphere, like we were making this class

photo. There was a sense that superstars would mingle with other

members of the film industry without any sense of difference.

Everybody knew that film is hard work and we share this hard work,

we share this effort, and we share this commitment to the medium. So

that was very pure and nice, the atmosphere.

What's next?

I've barely

had a chance to build up a new film because I've been so busy with

this for a long time. So that's actually what I'm hoping to get

started thinking about once this is finished.

It will be something stylistically different?

Oh yeah it

might be entirely different. I just follow whatever story fascinates

me.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.