PopEntertainment.com >

Feature Interviews - Actors >

Feature Interviews K to O >

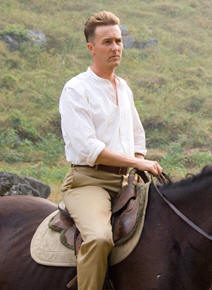

Edward Norton

Edward Norton

Lifting the Veil

by Jay S. Jacobs

Copyright ©2006 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

December 29, 2006.

When

you think of actor Edward Norton, chances are you think of gritty modern

urban dramas Ė like Fight Club, American History X, The 25th

Hour, The Italian Job, The People vs. Larry Flynt or Primal Fear.

The always interesting actor has been looking backwards in 2006,

though, doing two straight period pieces. Earlier

in the year, Norton starred with Paul Giamatti and Jessica Biel in the

old-fashioned magician drama The Illusionist.

His

newest project is a labor of love. Norton has been trying to get together

an adaptation of the classic W. Somerset Maugham book The Painted Veil

for years. He has worked with screenwriter Ron Nyswaner

(Philadelphia) for about seven years to update

the story of a British doctor in the 1920s who learns his wife has had an

affair and drags her to a Cholera-plagued town in China.

ďItís been a long process,Ē acknowledges Nyswaner. ďOn the

script, Edward encouraged me to embrace the central theme, which is the

grace that comes with forgiveness. In a book, which has a narrative voice

and explains whatís going on in someoneís head, you actually can have the

luxury of having characters who remain very, very bitter until the end. You

somehow rise above that bitterness and have that experience. In a movie,

you have to embrace one thing or the other. I think we moved away from

Walterís bitterness so that we could make him ultimately pull forward. Itís

about transformation.Ē

Norton knew from early on that Naomi Watts would be the perfect actress to

play Kitty, the spoiled wife who learns to respect her husband in the midst

of tragedy. Watts signed on right away and

suggested an old friend, John Curran, as director.

Curran had previously directed her in We Donít

Live Here Anymore.

ďMy

process is to find out their process always,Ē says Curran. ďI really donít

think I have some sort of magical genius that I can give Edward Norton

thatís going to make him a better actor, you know? The best thing I can do

is create an environment that inspires him and then just get the hell out of

the way. Thatís kind of the way I view it.Ē

Edward Norton sat down with us at the Regency Hotel in New York a couple of

weeks before The Painted Veil was to open nationwide.

Can

I start by asking you about filming in China and what it was like?

It

was a great experience. I think when you make movies, a lot of times the

artifice of the experience is very present all around you. So youíll be

creating a reality when you step out of work or head home. Itís not that

often that the experience of making the movie has a lot of parallels to the

experience the movie has in the story. But, it was in this case. We were,

obviously, far from home. We were working through the difficulty of

translation. Sometimes the inefficiency of communicating that way. People

doing things differently than youíre used to. Having your own problems

being away because youíre often in another context. A lot of it said very

directly what the story is about, and that was special. Other than that, it

was great. You know, there are attendant frustrations to making anything

way out in places where there arenít any paved roads and things like that.

But those logistical challenges were minor compared to I think how great the

Chinese crews and our colleagues there were amazing. They were really

good. Their work ethic is unbelievable.

What was it about the film that caused you to want to do it?

What was it about the film that caused you to want to do it?

For

me, it was a combination of two things. One is thatÖ if you watch David

Lean films, or Out of Africa, selfishly, you

canít help but think how great it would be to have that kind of experience.

So, when you see the potential in something for that kind of scope, itís

very tempting. But, the best of those movies, I think, are the ones that

have themes at the heart of them that transcend the period. When I read it,

I found myself more moved by this story of these people going through the

process of losing their illusions about each other and managing to recover a

deeper sense of each other. I related to it more than I tend to relate to

stories about wedding planners and things like that. For me, it was the

combination of the epic scope of the film but with but with a set of themes

at the heart of it that held it together.

Were you familiar with

Somerset

Maughamís writing before?

I

had read a few of his things. I had not read The Painted Veil. I

read Ronís script before I read the book. I went back to the book and then

in a way moved on with the script. Up and away from the book.

Your character is really different from the book. A lot more extreme in the

movie, I would say. With adaptations, how did you change?

In

some ways, I think the Walter of the book is more harsh. In the sense only

that in the book, many of the same things that happen in the movie happen,

but they happen in different ways. In the book, she has to go back to

Charlie after his death and sleep with him again before she realizes how

thoroughly awful he is. In the movie, we moved that recognition further

forward. In the book, the impact of the experience with Walter finally

lands when she goes home and in some ways confessesÖ asks for

forgiveness from her father. In the film we made that happen between her

and Walter, before his death. But as Ron said, we never wanted to abandon

the basic idea of a woman confronting the limitations of her view of life.

We wanted to let those changes take place between those two characters.

What

do you particularly like about this character?

What

do you particularly like about this character?

About Walter? Well, itís not so muchÖ I think I understand what youíre

saying, but I never look at a character and decide whether Iíd like to have

a beer with himÖ

No, I mean as an actor, why is he an interesting role to play?

Just

that he has so many levels to him. Heís a character who on first

impression Ė much as she perceives him, the audience has a chance to perceive

him Ė heís a little bit antisocial and heís very cerebral. As the

story goes on, these kind of unsuspected depths keep getting revealed in

him. The depth of his passion. The depth of his capacity to be hurt. To

be vengeful. He becomes almost violent... certainly psychologically

violent. That too, even gives way to a kind of humility and compassion that

you donít see in him in the beginning. So as an actor, you sit there

looking and go, wow, this guy is quite an onion, you know? He keeps going

layer to layer. I think Kitty [is] equally [complex]. Thatís what makes it

a very complicated little dance that those two do.

Can you explain how Chinese culture inspired you?

I

should say, I didnít go looking for a film about China. The fact that I had

some background in China just made it more appealing because I had

encountered it. But, you know, at the moment it happens to be the biggest

country on Earth. (chuckles) Itís also one of the oldest cultures

on Earth. In a lot of ways, China is a lot like America, in the sense that

itís too vast to really encompass. Usually people are going to make general

statements about it. Itís geographically diverse, like America. Itís

ethnically diverse, like America. It has this deep, deep history. So to me

itís a fascinating place. Also, right now, this is what the storyís about Ė

itís in flux. Itís a place where enormous changes are happening. Itís

palpable. The moment when the story takes place, it was another moment in

which change was ripping across that country and people were

asserting their right to throw off the shackles of other countries meddling

in their affairs. Itís an interesting component.

So

the alien helped to reinforce their acclimation? That was important to

happen in China? Could it have been anywhere else?

So

the alien helped to reinforce their acclimation? That was important to

happen in China? Could it have been anywhere else?

I

think you can argue this could take place in a similar kind of historical

moment in another place. You could change anything in a number of books.

In this case, I think, itís not really a part of the book, but John Curran

brought a specificity to the historical moment in the film. Pushed me

and Ron to get more specific about when this was taking place and what was

going on. In part, because I think we thought that was smart because it

resonated with things weíre seeing today. But, also, to be honest, I think

itís just because John is a good dramatist and he looked at it and said how

can I create an environment around these characters that drives them closer

together. Beyond cholera, what could be going on? He found this moment in

Chinese history when foreigners were being attacked all over the country

side. You know, itís just good drama.

In the story Walter was doing things that the Chinese had issues with

spiritually. Did that happen in the filming as well, where there were

Western things they did not understand or approve of?

Well, to make sure itís not misinterpreted, the people in the town we were

filming in didnít get angry. The scene in the film is that Walterís

insistence on the bodies being removed violates the Buddhist tradition of

the body being allowed to rest so the spirit can depart. I think the

Chinese people we were working with; the more we gave voice to the Chinese

perspective on peopleís intervention on their affairs, the more the Chinese

people we worked with felt even more deeply connected to it. It was fairly

late in the process where we wrote that scene where Walterís saying to the

Colonel at the campfire, I donít get your beef with me. Iím here doing the

best I can. The Colonel says, I understand that, but your country is

pointing guns at our country. The more we gave the Chinese

perspective, the more it gave it resonanceÖ even for our Chinese

colleagues.

Can you talk about working with Naomi?

Oh,

sheís supreme. I totally canít say enough good about her. Iíd say beyond

any film Iíve ever worked on

Ė the two performances were like in lockstep.

There was no way to do one without the partner. Without the other. They

are so intimately intertwined. Itís definitely the closest Iíve ever worked

on a day-to-day level with another actor. It was just fantastic, because

sheís so unafraid to work at levels of nuance. Itís really a challenge.

Itís really great. Because sheís putting things over so subtly.

Thereís

stuff in the film that she does that I just love. I love

that whole sequence with her and Diana Rigg, because sheís not really saying

that much, but you feel the impact of this perception of Walter washing over

her to the point where she walks out and kind of canít speak. That kind of

work is so important. Itís the best of what you can do in film

acting, because itís almost gestural. Itíd be like sheís got a great

feeling for how much the camera can draw out of you. I could not have had a

better partner.

You

are very involved in environmental issues. Which Presidential candidate do

you think could do the most for the environment?

You

are very involved in environmental issues. Which Presidential candidate do

you think could do the most for the environment?

You

know, I think itís a complicated question. I donít have a glib answer for

it. I think I need to do a little more specific looking into what people

are proposing on those levels.

You said you and Naomi felt really in tune with one another. Could you talk

a little about how you got there and how you worked with John?

Well, Naomi and I talked for a couple of years. She was involved also for a

long time. A lot of times, we actually wrote a lot about it, which was

really interesting, because the differentÖ

Like letters to each other?

YeahÖ I meanÖ not pretending to be the characters or anything. Just kind of

noodling on what we related to. Also, because the script was always

developing Ė debating how far are we going to take this film? How overt is

the forgiveness? How much do you want them to say on the deathbed? What do

you need expressed? How much of it can be expressed in words? And how much

of it without words? All that kind of stuff. Then, of course, the both of

us relied on John enormously. She had a long relationship with John.

Theyíd known each other for fifteen years and had already done one film. So

that was great. We had to shoot this film profoundly out of sequence. Do a

lot of the deep scenes of their relationship in the middle of the movie

without having shot any of the beginning. That relies a lot on the director

going, ďDonít worry about hitting it perfect. Letís do pitch one here and

pitch one here and pitch one here and pitch one here and give me the raw

materials to sort it out later. I think that requires an enormous amount of

trust in a director. You have to be willing to essentially fail. Do a take

that may be clownishly wrong. You need a lot of trust among everybody.

Features

Return to the features page