PopEntertainment.com >

Feature Interviews K to O

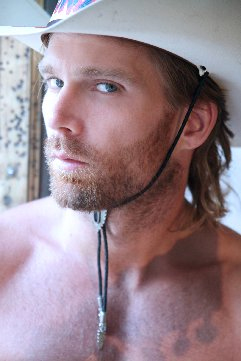

> The Naked Cowboy

The

Naked Cowboy

The

Naked Cowboy

On Broadway

by

Ronald Sklar

Photography by Eugene Gallegos.

Copyright ©2006 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

August 24, 2006.

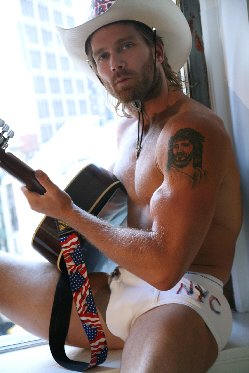

Robert Burck, aka The Naked Cowboy, stands at the crossroads of the

world, a prism strumming a guitar. Through the millions of people who

curiously walk by him, marvel at him, laugh at him, laugh with him, narrow

their eyebrows at him, pose with him (he claims to hold about twenty

babies a day) and/or call him a fag, he finds his personal inner peace.

He’s the worst dream in your dream journal: hey, I dreamt that I was

standing in the middle of

Times Square in only my underwear, playing a guitar.

Burck, however, is in a waking state. In fact, he couldn’t be more awake,

more alive. During the daylight hours, he’s doing the flickering and the

reflecting long before those famous lights come on at night.

He

says, “I’m literally going out of my way to do what nobody else is doing

for no reason at all with no purpose. How far can I get doing absolutely

nothing?”

Pretty damn far, apparently. Through the law of

easement, The Naked Cowboy has

become a Times Square fixture, making personal

appearances in the photo albums of millions of tourists

from the four corners of this lonesome rodeo we call a planet. His refusal

to go away has lead him to an upcoming underwear line at Walmart, a

proposed reality show, a recording contract, national commercials and

countless TV and radio appearances. In addition, he performs at Mardi Gras

in New Orleans

and during Biker Week in

Daytona Beach.

And lest anyone forget, he collects business cards from everybody he’s

ever met in his entire life, and sends handwritten updates on his career

on a regular basis. His fifteen minutes of fame are being stretched further

than his hamstrings.

His

goals don’t stop there. He says, “Financially, I want to be the most

celebrated philanthropist of all time. Physically, the best-built man in

the entire world. And the most celebrated entertainer of all time. I’m

going to extend the boundary of what anybody ever conceived possible in

every single realm. People will say, ‘That guy had no limit.’”

Mind you, he’s not really naked and not really a cowboy. He hails from

outside Cincinnati, but sounds like a good-ol' boy from the hills of Georgia,

with the mind of a deep thinker and the body of a long-distance runner (he

participates regularly in New York City marathons). His delivery, though,

is less of a jaded

Manhattan

transplant and more of a Sunday-morning-TV preacher, very confident and

articulate, determined to give a message.

Mind you, he’s not really naked and not really a cowboy. He hails from

outside Cincinnati, but sounds like a good-ol' boy from the hills of Georgia,

with the mind of a deep thinker and the body of a long-distance runner (he

participates regularly in New York City marathons). His delivery, though,

is less of a jaded

Manhattan

transplant and more of a Sunday-morning-TV preacher, very confident and

articulate, determined to give a message.

“The entire world knows who I am,” he says. “There is no escaping that

every single person knows me. Period. I am going to be a symbol of this

age. This is a commercial age. But they’re seeing a guy out there giving

complete humility of heart, you know, the crazy guy in New York City kind

of thing.”

His positive self-image may not match the perception of many onlookers,

who – well, don’t know what to make of this image, positive or otherwise.

“I’m amazed at how many people think I come out of the subway system,” he

says, “and they think, wow, he doesn’t stink. Like I’m some kind of

homeless guy who just happens to be organizing this year after year after

year.”

On

the contrary, Burck is out there daily, stuffing the

tips that

make his living into his boots. He drives his SUV into the city from Secaucus, New

Jersey, where he stays in a fifty-dollar-a-night motel. He changes out of

his clothes in a parking garage, and takes the short walk to 45th

and Broadway in his unmentionables. In New York, barely anyone notices (emphasis on the barely).

He

says, “When I go out there, and I’m playing, and I truly block it all out,

I’m not looking for anything, I’m just doing it. I’m really just focusing

on playing the songs to the best of my ability, and looking up into the

sky and taking my focus away from the objective world. The crowd lines up,

they’re everywhere, they’re attacking from every direction. When I want

their attention, I don’t have it. To the degree that I don’t care, I take

all the attention. Like a monk, it’s action-less action. [Monks] have

literally become one with what they are doing.”

His beginnings were not particularly humble, but unlikely. He was born and

raised in the

village of

Green

Hills, Ohio, his father being the famous genealogist Ken Burck. “My dad is

German, and all about organization. He’s a genealogist and mayor of the

town. It was painful then [to be raised by such an organized, ambitious

person], but as an adult, I’m all organized. Everything is perfect. I

don’t screw around.

“I

was a little bit chunky in fifth and sixth grade,” he recalls. “One day, I

went running and I sweat. I came home and said, ‘hey, ma, look, I sweat!’ I

felt like an adult. So I started running every day. Before long, I lost

ten pounds. Mom said, ‘don’t lose any more,’ and that’s all I needed to

hear to go anorexic and go to a shrink for years. But it was all about

getting a result. It was the whole control issue. I had to be the center

of attention. My parents got divorced when I was a little kid. It was that

whole, ‘I want my mom and dad to be together’ kind of nonsense. There was

always an incredible amount of force behind what I was doing, but no

direction. Anthony Robbins turned it all around for me.”

“I

was a little bit chunky in fifth and sixth grade,” he recalls. “One day, I

went running and I sweat. I came home and said, ‘hey, ma, look, I sweat!’ I

felt like an adult. So I started running every day. Before long, I lost

ten pounds. Mom said, ‘don’t lose any more,’ and that’s all I needed to

hear to go anorexic and go to a shrink for years. But it was all about

getting a result. It was the whole control issue. I had to be the center

of attention. My parents got divorced when I was a little kid. It was that

whole, ‘I want my mom and dad to be together’ kind of nonsense. There was

always an incredible amount of force behind what I was doing, but no

direction. Anthony Robbins turned it all around for me.”

Robbins, the positive-thinking guru, and his books came into Burck’s life

just after a healthy bout with juvenile delinquency. Robbins’ program of

self-empowerment went to Burck’s well-sculptured head, as he pursued a

living as a stripper and a model, eventually posing for Playgirl

(“trying to be somebody,” he explains).

He

says, “I became quickly aware – because [Robbins] makes you aware, that

the life you are living is the life you are creating. I had been a punk

with no direction. Anything that caught my fancy, I was doing it. And I

was doing it full force. [Before Robbins,] I was caught up with everything

but I had no sense of direction.”

Picking up Robbins’ books inspired him to learn from other philosophical

cowboys.

“I

went from Robbins to [Ralph Waldo] Emerson and

[Friedrich] Nietzsche,” he says. “My grandparents

always called me Mr. Grandiose.”

He

reflects, “When I first started as The Naked Cowboy, I was looking for a

vehicle. It was all egocentric. It’s impossible to be embodied and not be

egocentric. You’re a vehicle for whatever you’re trying to communicate. At

first, I just wanted the fame, the car and all that goes with it. There is

a different quality behind it now. But even if I want to be totally

spiritual and holistic, there is still desire. But what’s the difference?

Both are a vehicle of power to say, ‘I’m everything.’ Emerson says: ‘Life

is a search for power.’ But what is power? For me, it is just the ability

to be with everyone at once. To be completely at peace in the world.”

This goal is a challenge to say the least, when you’re both naked and a

cowboy and playing for people on vacation or on their lunch break.

He

thinks of his typical day at the office: “Smackin’ my ass, pullin’ my

hair. Somebody yelling, you fag. It’s high intensity. It’s the

opposite of living in a cave.”

He

thinks of his typical day at the office: “Smackin’ my ass, pullin’ my

hair. Somebody yelling, you fag. It’s high intensity. It’s the

opposite of living in a cave.”

When asked how he comes down from that, he responds, “I leave.”

He

sums it up thusly, “And what did I do: I just did one simple thing. I

obeyed my own instincts. I did not get attached to anyone or anything.

Jesus, Buddah, all of them, they all said the exact same thing: that you

are that force, that you are identical with the Father, that you are one

with God. That’s it. And as you separate yourself, the whole world can

come and go [but] I am God. [I’m] looking at the world without judgment,

and letting all come and go without bringing any judgment. I become a

window for them to look at themselves. Whether it’s a man shaking my hand

and saying, ‘You’re a wonderful man. I really respect what you do,’ or a

drunk that says, ‘You don’t belong in this town, you loser,’ I’m just

watching them report themselves back to themselves.”

And Robert Burck as The Naked Cowboy continues to report for duty, at the

very center of that

blinking yet

unblinking intersection.

“I’m contributing value at all times,” he says. “I work all day and give

it everything I got.”