“I’m Harvey Milk, and I’m here to recruit you!”

This was the battle cry of 1970s San Francisco politician Harvey Milk,

the first openly gay man voted into public office – and a man who was

assassinated in office with the Mayor of San Francisco in 1978.

Milk has become an icon of the gay community, but despite the fact that

at the time the story was media catnip (the killer used the infamous

“Twinkie defense”), the murder of Harvey Milk has been pretty much

forgotten by the world at large.

However, it became an obsession for relatively unknown screenwriter

Dustin Lance Black, an out homosexual who found strength in the story of

the politician. He wrote Milk, a screenplay which has been now

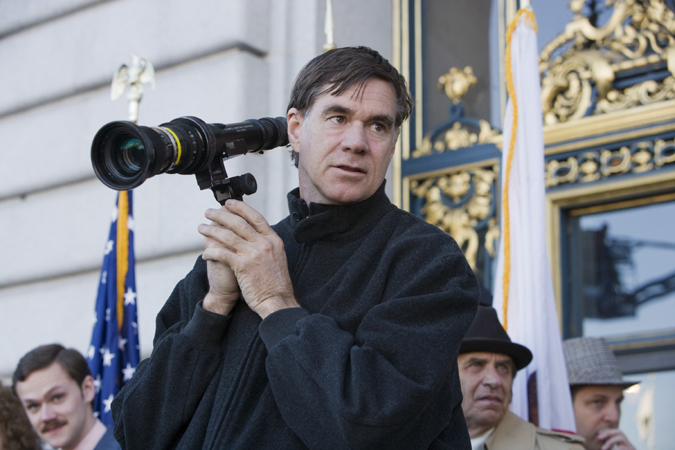

brought to the screen. It is directed by acclaimed screenwriter Gus Van

Sant and stars a wonderful ensemble – with Sean Penn doing Oscar-caliber

work as the trailblazing politician, James Franco as his lover and

campaign manager, Josh Brolin as the colleague who ended up killing him

and Emile Hirsch and Alison Pill as the campaign workers who helped

bring Milk to power.

Thirty years later, with Proposition Eight failing in California –

denying gays the civil right to get married – Harvey Milk’s message is

more important than ever.

Most of the major cast members, as well as the screenwriter and director

of Milk held a press conference in the Regency Hotel in New York

a little over week before the film’s opening to

discuss Milk and his message.

All of you came from

a wide variety of vantage points to make this movie. Can you speak from

an artistic or aesthetic standpoint of what was it that made you need to

do the movie? Were you at all scared to take on this subject matter?

Sean

Penn: I

don’t know if there’s such a thing as saying you’re scared to make a

movie. There were challenges in this that were exciting. It started

with Gus Van Sant. I think that all of us here, any actor with a hunger

to create something fantastic wants to work with Gus. There was that,

and he gave me Lance's sensational script. It seemed a no-brainer. I

knew, of course, then I could lay on top of that all the values that

this story and that Harvey Milk's life have, but that would take a long

time. But, those were the initial attractions. It was a

wonderfully-written script with one of the great directors.

Sean

Penn: I

don’t know if there’s such a thing as saying you’re scared to make a

movie. There were challenges in this that were exciting. It started

with Gus Van Sant. I think that all of us here, any actor with a hunger

to create something fantastic wants to work with Gus. There was that,

and he gave me Lance's sensational script. It seemed a no-brainer. I

knew, of course, then I could lay on top of that all the values that

this story and that Harvey Milk's life have, but that would take a long

time. But, those were the initial attractions. It was a

wonderfully-written script with one of the great directors.

Dustin Lance Black:

To me it’s a pretty simple answer. It was a very personal story. I

heard his story at a time when I needed to hear it as a teenager, and

you know, it's not out there anymore. I asked my friends: “Do you know

who Harvey Milk is?” They were like, “I don’t know, some dairy salesman

or something?” They have no idea. It’s important that it be out there

– his message be out there. I think that’s pretty clear. So, it came

from a personal place. Something that’s still very, very important.

Alison Pill:

I was embarrassed to not have known anything beyond a sort of vague

notion of the “Twinkie defense.” The fact that that is his legacy… or

has been… and having read the story, I just went, how has this not been

out there? It’s pathetic that I didn’t know it. That he’s not as

important a historical figure as he should be. It’s sad. I hope this

sort of rectifies that.

Josh Brolin:

I had a very visceral reaction to the script. Somebody else, I think

Matt Damon, was supposed to play Dan White at a certain point. I read

the script and cried at the end. Gus had also sent me the 1984 amazing

documentary (The Times of Harvey Milk) that I watched with my

daughter. Both of us were crying at the end of that. It was one

of those things – it was less about the character, more about the

story. The fact that we were so moved by it. I think the last time I

felt like that was, I did a movie a long time ago called Flirting

with Disaster. I remember watching it and I was so happy to be in

the film. Actually watching the film, you are able to objectify. I’m

just happy I’m in this film. I love that this film exists. It was the

same thing, the same feeling with this.

James

Franco: I

was in London and my agents called me and told me that Gus was going to

make this movie about a guy named Harvey Milk. I grew up in the Bay

area, in Palo Alto, 45 minutes from San Francisco, and I didn’t really

know who Harvey Milk was. I did a little research. I was surprised and

sad to find out that it wasn’t known. I was amazed by who he was and

sad that nobody was really talking about him. I was born the year that

he died, 1978, and it was just an incredible story.

James

Franco: I

was in London and my agents called me and told me that Gus was going to

make this movie about a guy named Harvey Milk. I grew up in the Bay

area, in Palo Alto, 45 minutes from San Francisco, and I didn’t really

know who Harvey Milk was. I did a little research. I was surprised and

sad to find out that it wasn’t known. I was amazed by who he was and

sad that nobody was really talking about him. I was born the year that

he died, 1978, and it was just an incredible story.

Josh Brolin:

Were you born that late? (laughs)

James Franco:

Emile was like in

the 80s.

Emile Hirsch:

You’re trying to

rat me out.

James Franco:

And, uh, without even reading the script, I wrote Gus an email from

London and I said to him I’ll do anything in this movie, just to be a

part of it. I would have played the pool guy. Gus is very low key and

his emails are very low key and he was, “Yeah, we’ll meet in LA, if

you’re there.” We did and fortunately he gave me a better role than the

pool guy.

Emile Hirsch:

The pool guy is going to be pissed when he hears that.

Gus Van Sant:

I think that one thing for me was for a while… I've done a few films

that had gay characters, but not super positive gay characters. I heard

about the project through Rob Epstein (director of The Times of

Harvey Milk), who had heard that Oliver Stone was no longer going to

make a version of the film that was at Warner Brothers. I was

interested in it and got wrapped up in studying it. Political stories

are always really interesting to tell, but they are often avoided

because it can get… I guess boring, basically. Harvey’s personality was

a way to kind of have a character who resembled somebody like Abbie

Hoffman, almost, who was running for political office and then also at

the same time represented his gay community. It was sort of like an

amazing opportunity to have all these things in one story.

Emile Hirsch:

I of course wanted to work with Gus, and with Sean and all the other

actors. But as soon as I saw the documentary – I didn’t know anything

about the gay community in San Francisco or Harvey Milk, but I did know

many gay people growing up. Some were very good friends of the family –

my mother’s – and one of them actually died of AIDS when I was about

fifteen. I’d known him ever since I was walking. He was a really great

guy named Mark. This for me was a chance, I was able to learn more

about the history of some of my family’s really good friends and learn

where they were coming from. I really wanted to be a part of that.

This film was filmed

entirely on location in San Francisco. What kind of experiences did you

have with people in the city where this actually occurred?

Josh

Brolin: I

stayed above Castro [the section of San Francisco that Harvey Milk

lived]. I was staying in my ex-wife’s brother’s apartment. I was on

the Hill overlooking the Castro. I was afraid when I would go down to

the grocery store that I was going to be shot. The whole thing with San

Francisco, it embraced this movie so much. When I would go shopping I

was actually afraid of how people would react, because I know all of San

Francisco loved that this movie was being done period. What ended up

happening was, people would say, “Hey, you’re playing Dan White. You’re

doing the movie on Harvey Milk.” And they were so incredible. The city

itself, as a whole, they were so supportive. We just had the premiere

there. It was incredible. The feeling. The ambience. This was before

the election, so Prop Eight, that whole thing, they were fighting it.

As a whole, it was an incredible, incredible, goose-pimply experience to

be able to do it there.

Josh

Brolin: I

stayed above Castro [the section of San Francisco that Harvey Milk

lived]. I was staying in my ex-wife’s brother’s apartment. I was on

the Hill overlooking the Castro. I was afraid when I would go down to

the grocery store that I was going to be shot. The whole thing with San

Francisco, it embraced this movie so much. When I would go shopping I

was actually afraid of how people would react, because I know all of San

Francisco loved that this movie was being done period. What ended up

happening was, people would say, “Hey, you’re playing Dan White. You’re

doing the movie on Harvey Milk.” And they were so incredible. The city

itself, as a whole, they were so supportive. We just had the premiere

there. It was incredible. The feeling. The ambience. This was before

the election, so Prop Eight, that whole thing, they were fighting it.

As a whole, it was an incredible, incredible, goose-pimply experience to

be able to do it there.

Alison Pill:

Just the fact that we were able to get – was it 3,000 volunteers? – just

to come down to Market Street in the middle of the night and walk up and

down for the candlelight march. It was an amazing night to watch.

Across generations, across sexuality, just a group of San Franciscans

getting together and being a part of the movie, because it is important

to them and an important story to tell. It was an amazing night. It

was unforgettable. Gus has a great strength in using location as a

character. It couldn’t have been done anywhere else. I think it shows

in the movie.

Dustin Lance Black:

It was all so great. I was so excited to find out that we got to do it

there. And that we got to do it right around all these people that I

had been spending all these years with, like Danny Nicoletta [who was

played by Lucas Grabeel in the movie] or Anne Kronenberg [played by

Pill]. Cleve Jones [Hirsch’s character] came up to San Francisco. To

have the real people who this film is based on around for us to use as

resources and inspiration – it’s invaluable. Now, I think it helps that

we have an even more extended family that reached out to the truth of

where this story came from. It was really fantastic.

I was wondering if

you could speak about what just happened in California with Proposition

Eight. In the movie, Milk was fighting Proposition Six. What does it

say that civil liberties are still being put to the popular vote thirty

years after Harvey Milk?

Dustin Lance Black:

I have sort strong feelings on that. I think it’s sad that Proposition

Eight ended up looking a lot more like Dade County [another famous vote

on gay rights mobilized by Anita Bryant in the 70s] in the film, where

the gay movement went down, than Proposition Six, where Harvey Milk,

through his strategy, was successful. I think gay people and the gay

movement need history like this so they and we don’t keep repeating the

same mistakes. I think if you were watching the No on Eight fight, you

really didn’t see a lot of gay people representing themselves. There

weren’t gay people in the commercials or saying gay and lesbian in a lot

of their literature. That was really one of the lessons of Harvey

Milk. So, in that way, I hope it’s helpful. I hope it motivates the

gay and lesbian community to start that outreach and education and have

some pride in a way that gets us to meet our neighbors again and put a

face to who is being hurt. I imagine that will help it.

You caught Harvey

Milk’s mannerisms and gestures really well. How did you prepare for

that?

Sean Penn:

The documentary and also additional archival footage was, I’m sure, very

helpful. I say that a little vaguely because with that sort of thing,

the best way you could use it was that you watch a lot the same way

you’d play music all day in the background and not necessarily be

thinking about it. But just I kept it on all the time and over a period

of time, the little synapses start to connect. If you listen carefully,

you can hear the music of that and you kind of dance with it. That and,

of

course,

what Lance wrote – it comes from all directions. It was clear, at

least, in terms of, for a lack of a better term, character choice that

the most exciting version of Harvey Milk to me was Harvey Milk. If you

see the documentary, the guy is the movie star of that documentary.

He’s an electric, warm guy. So you just reach and reach and reach.

You never assume you’re going to get all the way there, but you figure

that with the help of a director and a screenwriter and all the other

things that a movie is that you can get the spirit of it out there the

best you can.

course,

what Lance wrote – it comes from all directions. It was clear, at

least, in terms of, for a lack of a better term, character choice that

the most exciting version of Harvey Milk to me was Harvey Milk. If you

see the documentary, the guy is the movie star of that documentary.

He’s an electric, warm guy. So you just reach and reach and reach.

You never assume you’re going to get all the way there, but you figure

that with the help of a director and a screenwriter and all the other

things that a movie is that you can get the spirit of it out there the

best you can.

Did any of you get to

meet with the real-life counterparts of your characters? What notes did

you take from them? What sort of things did they mention?

Emile Hirsch:

Well, I played Cleve Jones in this. He was there every single day. I

was able to spend a lot of time [with him] beforehand. The first thing

I got from him was he was just very mischievous and very funny. That

was something I thought would be really important. Also, it was really

a way that Cleve, I think, probably bonded with Harvey – was over

humor. They would kind of go at each other. That was a way of

bonding. He had amazing stories about Harvey. Harvey was just the most

amazing guy to him. Cleve feels like Harvey really shaped his life and

put him on course for who he was going to be as a man. Cleve was also

very instrumental to me in just learning about the Castro, and learning

about San Francisco and the movement. What it was like psychologically

to be a younger gay guy back then. He also wanted to debunk some of the

myths about Castro, like the bathhouses. He was like, “You probably

heard of these bathhouses. There’s a lot of myth about that. Back in

the 70s, this was the most fun thing in the whole world. There was no

HIV. We were these really repressed young guys who got an opportunity

to go into the ultimate candy store.” And he was like, “we had an

amazing time.” So, he was able to debunk a lot of the myths about it.

Alison

Pill: It

was amazing to meet Anne. She wasn’t on set as much as Cleve, because

she is very busy being the deputy director for Health in San Francisco,

still. But I did get to hang out with her and her daughter. It’s nice

to have somebody to ask questions – in terms of more general background

stuff. It might not make it into the movie, but just to know. What did

you do on Friday nights? Where did you live? Just the more general

stuff that when you absorb, it sort of filters into the rest of it. She

also was able to point out – in the midst of all this – how similar a

political campaign can be to making a film. These long hours of sort of

living in a vacuum. In terms of a lot of the scenes, you end up feeling

you’re part of it.

Alison

Pill: It

was amazing to meet Anne. She wasn’t on set as much as Cleve, because

she is very busy being the deputy director for Health in San Francisco,

still. But I did get to hang out with her and her daughter. It’s nice

to have somebody to ask questions – in terms of more general background

stuff. It might not make it into the movie, but just to know. What did

you do on Friday nights? Where did you live? Just the more general

stuff that when you absorb, it sort of filters into the rest of it. She

also was able to point out – in the midst of all this – how similar a

political campaign can be to making a film. These long hours of sort of

living in a vacuum. In terms of a lot of the scenes, you end up feeling

you’re part of it.

James Franco:

I played Scott Smith [Milk’s lover and early campaign manager], who

passed away in the mid-90s, so I never had a chance to speak to him. I

read a bunch of stuff and watched the documentaries. They were very

helpful to kind of get a sense of the time. But Scott, as important as

I think he was to Harvey Milk, there wasn’t a lot of documented material

on him. So I really did have to depend on the stories from people who

knew him – Cleve Jones and Danny Nicoletta worked at the camera shop

with Scott. And other people, Frank Robinson. I guess the sense I got

and the side of Scott that we were depicting in the script was for the

most part, a supportive guy. Just based on the facts of their life

where Scott was there through big moments of Harvey’s life. When they

met, Scott was a struggling actor and Harvey was in the closet, working

in investment banking. Scott was there when Harvey decided he wanted to

come out, wanted to change his life. He was there when he moved to San

Francisco. Then he was there when Harvey decide he wanted to start a

political career. He was Harvey’s campaign manager, not knowing

anything about politics. Just being there, the fact that he was there

for all that shows me that maybe he didn’t know exactly what he was

getting into, but he was willing to support Harvey and do whatever he

could to help Harvey achieve what he wanted to do.

Josh Brolin:

I think the most informative – I don’t even know if I’m supposed to say

this or not – but the most informative thing for me was, I talked to

some cops who had known him and it ended up one of those cops actually

taped his confession. So, I heard the confession, which was extremely

revealing to me. There was a sense of arrogance, and then there was

also an incredible sense of a victim to it. The whole thing with him,

Sean at one point called me on the set. Charlie, who is Dan's son, he’d

gone out to dinner with him. [Sean] said “Do you want to meet him?” I

was, oh, damn, I don’t know. Also, it was the day we were doing the

baptismal scene. So it was him, we were baptizing him, basically, in

the scene. He was in Sean’s trailer and I went to go meet him. There

was a severe – as you can imagine – a severe reaction when I walked in,

with the mutton chops and clothes and the whole thing. He hasn’t seen

the film, I know that, but I think he was very happy once we spoke for a

while, that his dad was not being portrayed as the result of what he

did. It was more the question of, how did this really decent guy get to

the point – the incredibly frustrated point – where he felt like the

only power he could muster was doing something tangible like loading a

gun and shooting somebody in a cause and effect kind of thing?

[Also]

Cleve was great to have on the set all the time. When I saw Cleve the

first time, first of all, I could tell – you look in somebody’s eyes and

you can pretty much see – Cleve looked at me like, “Oh, he's playing

Dan? He's not very good. That's not right.” Then, I went away, and

which was a great kind of instigator for me and motivator. I came back

and we did the dress and haircut and the mutton chops and the whole

thing. The next time I saw Cleve, this was the reaction. [Mimes

gasping.] That really gave me a lot of confidence to be able to

build a character. I’m going in the right direction here. That was a

big motivator.

[Also]

Cleve was great to have on the set all the time. When I saw Cleve the

first time, first of all, I could tell – you look in somebody’s eyes and

you can pretty much see – Cleve looked at me like, “Oh, he's playing

Dan? He's not very good. That's not right.” Then, I went away, and

which was a great kind of instigator for me and motivator. I came back

and we did the dress and haircut and the mutton chops and the whole

thing. The next time I saw Cleve, this was the reaction. [Mimes

gasping.] That really gave me a lot of confidence to be able to

build a character. I’m going in the right direction here. That was a

big motivator.

Sean Penn:

I think Lance summed it up when he said that those people being part of

it created an extended family. You always hear about how one of the big

parts of a director’s job is setting the tone and the environment on a

set. A kind of broader version of that, I guess, is just the spirit of

something, you know. The way anybody in anything creative works, you

try to let the spirit move you. Well, there was a lot of spirit around

– and by spirit, it means, of course, practical information, which

sometimes it can help, sometimes it can overload you, it depends. But

from the cast of this movie, it was one of these movies where if the

director’s job was to create an environment, he did. It included that.

All of those people being there was very guiding.

How did Harvey stay

with you while you were playing him? How has he changed you?

Sean Penn:

The answer is

he did stay with me. How? I’m not entirely sure. I haven’t given it a

lot of thought. If something comes in and you become aware of it, it’s

there. You leave it alone so it doesn’t go away. In terms of humanly,

one likes to think that with each day and each person that comes into

their life directly or indirectly, that there’s some kind of growth –

hopefully in a positive direction. With him, it would have been but I

can’t identify [how]. Certainly in a very immediate way there’s been a

lot of… let’s say timeliness… to this story that we’ve all been thinking

about and reference this recent experience we had, but I can’t be more

specific than that.

While you played

him, did it impact your daily life?

Sean Penn:

My daily life consists of getting up at six o’clock in the morning and

making sure I’ve got my words together, that my kids are off to school –

if I don’t wake up in time, if I leave before them for work. Then I’m

at work all day. Then I’m exhausted going home and working with the

kids, learning a bunch more lines for the next day. So, I don’t know

that I had a daily life other than what’s on the screen.

The

gay movement has now become the new issue for civil rights. This movie

can create reaction and stimulate debate. Do you feel that way? Can

you talk about how you hope it will make people more conscious of these

issues?

The

gay movement has now become the new issue for civil rights. This movie

can create reaction and stimulate debate. Do you feel that way? Can

you talk about how you hope it will make people more conscious of these

issues?

Gus Van Sant:

Especially right now, with Prop 8 and the reaction to Prop 8, it’s

mobilized and brought together the gay community. Particularly, I

think, the younger gay community. It’s their time, and they’re taking

it to the streets. Just now I was interviewed by a gay writer in Los

Angeles and he had been to the first rally response to Prop 8 in Los

Angeles. He went to the West Hollywood gathering and there was a

speaker. Everyone walked away and walked up the street to Sunset

[Blvd.] – to his surprise, because he’d been to many rallies in West

Hollywood and this had never happened before. There’s a new energy and

that’s kind of inspiring. Our film is about a new energy of a different

time – a sexual liberation in the ’60s developing into people who found

their gay sexuality and who banded together in the Castro, which had its

own young energy at that time. Also the nuts and bolts of the political

strategies are hugely informative and inspiring in the movie. Mostly

inspiring. When it gets to play theaters I think it would definitely

play into that energy – the gay civil rights energy of today.

Sean Penn:

I’ve got to go with what Gus said. Even the word issue about

this, it’s only an issue because of ignorance in the first place. I

think if you could criminalize a lack of… we don’t have an excuse of

being ignorant of the law. If we could have no excuse to being ignorant

to human history, then, in fact, any support, for example, of

Proposition 8, would be, minimally, manslaughter. Human history tells

us there are going to be teenage boys who are going to hang themselves

out of a reach for identity they can’t get – in part because of things

like the issues like this, precious words like this and all of

the things that the whole history that any civil rights movement has

had. As long as it’s an issue, it’s an obscenity. If this movie is

part of an engine to help reveal that, that’s going to make all of us

really happy and proud.

I was wondering about

the use of archival footage in the film. Was that part of the script

originally or was that something that the director brought?

Dustin Lance Black:

For me the archival stuff came out of trying to write Anita Bryant.

It’s difficult. You start to just transcribe her words and it’s rather

unbelievable. To a modern audience, it’s really tough to believe that

someone said and meant the things she said and meant. And said it on

such a national platform. I just worried. I thought she might come off

as caricature. Or she might come off as evil in the pen’s black and

white portrayal. I didn’t want that. I wanted her to be the real

person. I thought, well, just let her speak for herself, so I wrote in

the script “actual footage of Anita Bryant.” That was my only

contribution to that. Then it was Gus.

Gus

Van Sant:

For me, it was probably indicated in the script, but there were a couple

of other things. There was a question of whether we’d be able to

assemble marchers, so I thought maybe we could just use footage that was

shot by the news – showing a large number of marchers. I knew that Rob

Epstein had images of the candlelight march, so that was possible, that

we could ask him to let us use that in the film. When we started

looking for these marches, we looked under anything that said Harvey

Milk on it. So we ended up with a really lot – twelve hours of footage

– and even wanted more. We went to the Hormel Library and the Gay and

Lesbian Archives in San Francisco and looked at home movies of the

Castro. I started to play with it when we were editing and really liked

what was going on. We also started to shoot the film with the idea that

we would actually shoot in 16mm. That sort of got changed while we were

working on it, but we really were going to go for the full-on

documentary [feel] throughout. It got changed, but the documentary

footage inspired that.

Gus

Van Sant:

For me, it was probably indicated in the script, but there were a couple

of other things. There was a question of whether we’d be able to

assemble marchers, so I thought maybe we could just use footage that was

shot by the news – showing a large number of marchers. I knew that Rob

Epstein had images of the candlelight march, so that was possible, that

we could ask him to let us use that in the film. When we started

looking for these marches, we looked under anything that said Harvey

Milk on it. So we ended up with a really lot – twelve hours of footage

– and even wanted more. We went to the Hormel Library and the Gay and

Lesbian Archives in San Francisco and looked at home movies of the

Castro. I started to play with it when we were editing and really liked

what was going on. We also started to shoot the film with the idea that

we would actually shoot in 16mm. That sort of got changed while we were

working on it, but we really were going to go for the full-on

documentary [feel] throughout. It got changed, but the documentary

footage inspired that.

Why did you decide

not to use 16mm and how did the combination of archival and regular

footage impact the movie?

Gus Van Sant:

It was all about the verisimilitude of bringing the audience right into

the actual period. The documentary footage always succeeded where it

was harder for us to succeed – when you were really watching the

period. And it was a sort of trick (chuckles) to draw the

audience into that period. The 16mm idea got waylaid because of fears

that we were shooting in a format that was unstable. (laughs)

We’re not as detailed as maybe our studio wanted us to be in. But we

kind of made it match, the way that we used it – the film stocks used.

As said before, since

November 4, there has been a dramatic escalation of tensions between the

gay and faith communities. I’m wondering how you think that may impact

the performance of the movie in the box office?

Gus Van Sant:

Well I think that we’re seeing both: There’s the raw hatred and there’s

also the support. I think it’s both sides playing out in the press and

in the community. That’s the nature of the battle, and it’s encased in

the film as well.

Dustin Lance Black:

But it’s also, I feel like Harvey Milk was great at grabbing headlines

and getting attention and getting it out there, so whether positive or

negative, it’s in the public dialogue again. That’s so important. If

that gets people to see the movie, fantastic, but I think that it’s just

great that it’s something that we’re all talking about again. I know

tuning into both the Democratic National Convention and the Republican

National Convention; I was so disappointed in both, because I thought:

Where are we? Where are gay and lesbian people? It felt like we were

off, we weren’t something that anyone cared to talk about. So, in that

way it’s exciting. I don’t care if it’s positive or negative, but it’s

a dialogue. That’s what’s really important.

Sean

Penn: I

also think it’s important to remember and remind people that the tension

is not between the gay and the faith communities. The tension is

between a gay community which, in fact, really is gay, and a

pseudo-faith community that has nothing to do with God, love or anything

of real faith. It’s really just hypocrisy and hatred. Any faith

community that deserves the title faith community really won’t

have a problem with these issues.

Sean

Penn: I

also think it’s important to remember and remind people that the tension

is not between the gay and the faith communities. The tension is

between a gay community which, in fact, really is gay, and a

pseudo-faith community that has nothing to do with God, love or anything

of real faith. It’s really just hypocrisy and hatred. Any faith

community that deserves the title faith community really won’t

have a problem with these issues.

You have a lot of

wonderful screen talent, but also a lot of wonderful theater talent in

this film. Alison of course has been in like eight of the best plays in

recent years, and Denis O’Hare and Stephen Spinella both have won Tonys

– both are out gay actors, playing uptight characters.

Gus Van Sant:

Yeah, they were

really great actors that we wanted to get in the film and were really

great for those parts.

Was it a choice or

was there an audition process?

Gus Van Sant:

There was an audition process. We did try and enlist the talents of as

many gay actors as we could. There weren’t that many that were of box

office stature, when it comes to major studios, so when it came to

roles, like Rick Stokes and John Briggs, those guys fit in very well and

were really great. I think it was very fun for both of those guys.

Alison, what was it

like to be the only lady on set?

Alison, what was it

like to be the only lady on set?

Alison Pill:

It was a great set to go to every day. Gus is incredible at lumping

together all these big personalities and people of different ideas – and

in really subtle ways making everybody feel like they are part of the

same thing. Going in, my first scene that I shot was coming into a

campaign office and being intimidated by a group of men. (chuckles)

It was my first day of shooting, so I was walking in, pretending that I

knew what I was doing. It wasn’t really hard to act that part.

I just love these guys. I couldn’t have asked for a more fun, more

thrilling set to be a part of. It’s like family.

Josh Brolin:

I said to Alison yesterday, because when we were on the set and she had

her frizz ‘do, I didn’t find her the least bit attractive. I was

looking at her last night, going “You’re so fucking hot!”

(all laugh)

Well what was the

atmosphere like on set? Was it a relaxed set?

Alison Pill:

I can also say what’s really cool about it is that I never looked at a

single monitor. I never knew where a camera was and I didn’t really

care. There were so many group scenes where we were all just sort of

talking and going through everything. I really had no idea what was

being shot. Every take was being on my toes. That’s a really

interesting way to work.

Can you comment on

the parallels between Harvey Milk and President Elect Barack Obama in

terms of them being galvanizing figures and the parallels between their

two campaigns – the platform of hope?

Sean Penn:

Well, that’s the first thing that hits any of us, I guess, because they

the word, "hope." I think at that moment in time – particularly

relative to the gay community in San Francisco that he was running to

represent – it was such a necessary part of what he was offering.

Similarly today for the whole world on any issue: anything that

represents hope. This might be our last shot at hope. So, yeah, there

are those obvious parallels. But I’m not going to tell you anything

you’re not going to write without me.

Gus, can you tell us

about the collaboration with Director of Photography, Harris Savides?

Gus, can you tell us

about the collaboration with Director of Photography, Harris Savides?

Gus Van Sant:

We’ve shot a number of things. I first heard about him doing a

commercial. The people who were putting the commercial together were

looking for a look – which is such a crucial thing in a movie. They had

shot with Harris in Europe. The showed me the commercial. It looked

pretty good. Then the clincher was they said that Madonna wouldn’t work

with anyone else. She needed Harris. And I thought: well, she must be

pretty discerning. And so it was kind of a thing. I got to use

Madonna’s DP!

Sean Penn:

DPs… Ex-husbands… (everyone laughs)

Gus Van Sant:

So first we did Finding Forrester together. Then we did the

Gerry, Elephant, [and] Last Days together. Harris is very,

very experimental, so one of the things on Finding Forrester was

we were shooting a scene and the characters were coming through a door –

and we did it through a window. Harris has an unique way of talking.

Harris is saying, “This should be the whole shot. Just this.” I’m

saying, this angle only? Just leave it all the way? They come all the

way through the door and all the way to the window. It’ll take five

minutes. I was paranoid. I said, we’re going to shoot it at other

angles, too. But, essentially that’s what we ended up doing in Gerry

and Elephant and Last Days. So we’d been through that

together, sort of forging certain aesthetics. When it came to Milk,

we’re always starting over from the beginning each time, so this time it

was the whole 16mm idea that sort of got derailed. He’s been great.

He’s an amazing visual partner.

One of the things I

thought was interesting was the sexuality in the film. It seems so

casual.

Gus Van Sant:

There were lots of scenes of intimacy in the movie that were either

suggested or not suggested in the script – between especially between

Scott and Harvey. The original “tryst” that they have in Harvey’s New

York apartment was actually our last day of shooting. So, by then it

was an interesting choice, it was quite quick, it was almost one shot.

It was easy. You know, with some sex scenes you know not to think about

it, or else you’re going to screw everything up. I think, speaking from

my point of view, at least, and probably the actors’ point of view as

well – overthinking is going to screw everything up. We just sort of

went ahead as if it were just one of the scenes.

Sean Penn:

Cleve Jones said something really great early on. We put together a

dinner with all the real people who had worked on Harvey’s campaign. He

said that one of myths is that we’re all just the same; it’s just the

sex that’s different. He said the reality is that we’re all very

different; it’s just the sex that’s pretty much the same. The

difference of course is living with bigotry and oppression and all of

that shit. That was something where our focus went. The rest of it is,

you know: for some people a guy gives him a boner. For somebody else

it’s a woman. So it was approached as: the sex is the sex is the sex is

the sex. The other part was really the heart of the picture.

Do you have any

thoughts on how the world would be a better place had Harvey not been

assassinated?

Do you have any

thoughts on how the world would be a better place had Harvey not been

assassinated?

Sean Penn:

I think less people would have died of AIDS. I think Ronald Reagan

would have been forced to address it, and it was a tragic loss. He

wouldn’t have stood quietly. He would have known. He was a leader and

he happened to be focused on the gay movement. Because the impression

was that this was initially – popularly the notion it was a gay disease,

and certainly huge numbers of homosexuals died related to it – I think

he would have advanced that argument a lot sooner. I think people are

dead because he died too soon.

As we’re heading into

the holiday season, can this movie play in Peoria? This isn’t

La Cage aux Folles. Do you think straight guys

particularly might be a little too queasy about seeing Milk?

Gus Van Sant:

I don’t see it that way, but maybe ultimately there’s some challenge. I

think it’s an intense movie, but very positive and uplifting. I don’t

know about the holidays.

It’s a very

competitive marketplace.

Gus Van Sant:

I do think it’s one of a kind within the marketplace.

Josh Brolin:

The one gay guy in Peoria can’t wait for this movie. (all laugh)

Can you talk about

making a biopic and staying away from some of the more sensational

aspects but being the story of one person’s life?

Dustin Lance Black:

For me it was focusing on one moment in someone’s life, instead of

trying to capture the entire life. Really focusing on who he was as a

man in that moment and what he was trying to do in that moment. It

becomes more about that moment within this movement than it does trying

to capture every little moment along a man’s life. It’s like a little

skipping stone trying to get the best of it. In that way, it was

possible to cut it down from being something that would need to be hours

long to being what it is today. To really capture the spirit of the

man. That was how I tried to go about it.

Gus Van Sant:

I felt basically the same thing. It was well chosen – the parts of

Harvey’s life that show [his impact.] Yeah, if you go through a

traditional biopic, there is that tendency: how can you not do every

part of a life? You end up with a lot of small scenes chained together

that are representative of a life – but maybe the drama gets lost

sometimes. Lance did a good job of choosing the rich parts.

Gus Van Sant:

I felt basically the same thing. It was well chosen – the parts of

Harvey’s life that show [his impact.] Yeah, if you go through a

traditional biopic, there is that tendency: how can you not do every

part of a life? You end up with a lot of small scenes chained together

that are representative of a life – but maybe the drama gets lost

sometimes. Lance did a good job of choosing the rich parts.

Can you talk about

the process of writing the script? How much research you did and how

long it took?

Dustin Lance Black:

Well, the first part of the question, I started in spring 2004. It was

meeting Cleve Jones that made me go from being a fan of the legend of

Harvey Milk to being kind in love and endeared to the real guy – who I

was starting to get to know through these real life people’s stories,

these more specific stories. It grew after a lot of work and driving up

to San Francisco a lot on weekends, to being this great family of people

who helped me get to know who this guy was, until it really got to the

point where I was a little bit haunted by this man I’d never met. At

that point you start writing. So, what is it now? Four years and some

change since then?

Also, with the hope

in the end, but still no one in real life talking about many of these

problems, how important is it for people to come out as Harvey said?

Dustin Lance Black:

I sort of talked about [this] a little bit. I think, yes, the end of

Proposition 8 looks a lot more like Dade County and Wichita [two earlier

civil rights losses from Milk’s era], and not just because it was a loss

to the gay community. Also because the strategy was so similar. The

strategy from Dade County was to send straight allies from California –

the Bay area – to Florida and have them represent the gay community,

instead of the gay community having its leaders represent the people of

the community themselves. That is one of the lessons of the film, to

the gay leadership and the future gay leadership. Although, I’ve got to

say, it’s really exciting. I was there on Wednesday night after the

election and the young guys and girls out in this audience that walked

away from the stage like Harvey said – they probably don’t know this

history yet. But I think instinctually they knew it was time to get out

of West Hollywood and march up to Sunset Blvd., a straight area, and put

a face to it. Say, “hey, it’s me that got hurt last night.” I think

there are some really good instincts in the young community that are

hopeful.

Features Return to the features page