Copyright ©2006 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

September 9, 2006.

The lure of Hollywood is a seductive one – a siren’s call promising fame,

money, love and power. People travel many miles, endure great hardships,

work demeaning jobs and face incredible competition – all in the quest to

capture the glimpse or possibility of stardom.

It

is almost a cliché now for an actor or actress to trek to endless

auditions long after hope of “the big break” has been extinguished. It is

almost unheard of for someone in the early phases of a promising career to

suddenly just walk away.

This brings us to Melissa Greene.

Greene is the child of show biz parents. If you know anything about

Hollywood, you know that very few people actually are from

there. Greene is one of those rare natives. Her mother was model and

actress Jan Wiley, best known as Dick Tracy's girlfriend in the original

1930s serial, as well as for small roles in Stagedoor, So

Proudly We Hail, The Best Years of Our Lives, and the classic

Citizen Kane. Her father, Mort Greene, was a longtime Red

Skelton Show staff writer. He was also a celebrated lyricist,

composing the words to “Stars in Your Eyes,” “Weary Blues” and “The Toy

Parade,” which became the theme to Leave It to Beaver. He was

nominated for an Academy Award in 1946 for “There’s a Breeze on Lake

Louise” from the film The Mayor On 44th Street.

“My father was multi-talented,” Greene says. “He was a cartoonist, played

piano, wrote lyrics and ended up writing comedy for Red Skelton. He was

also a wizard at self-promotion. And he loved to tell jokes – my

father was ‘onstage’ when he picked up his clothes at the cleaners!”

Greene inherited that gift for self-promotion. Or, more to the point, she

so wanted to be like her father that she emulated him. “I studied the

bold, zany way he presented himself to the world, then I did the same

thing… whether it was me or not.” Over the years, she mirrored the

careers of both of her parents, becoming a model, actress and songwriter.

In

the early 1970s, it appeared that Greene had the stuff of stardom. She

broke from the pack of unknown actresses by making herself “highly present

and conspicuous” at every audition, acting class, or studio

commissary. She regularly wrote notes to producers, on her letterhead,

explaining why they should hire her for a role in their show or film.

During an interview on the Universal lot, she remembers falling into step

with Walter Matthau, Jack Lemmon and Billy Wilder on their way to get

lunch, explaining that “…it’s important that you know me.” They agreed.

From then on, she would spend memorable afternoons with Wilder and his

writing partner, I.A. Diamond, sitting in their office, after her

interviews, “laughing and playing word games, amazed to be in the company

of legends.”

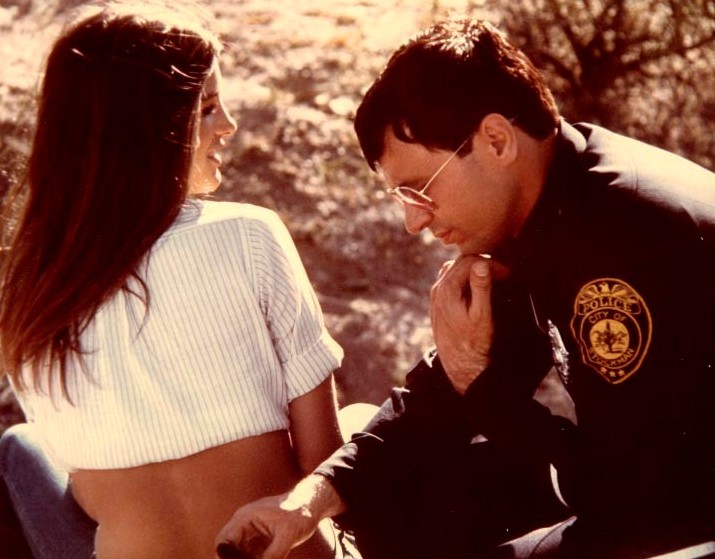

In

a brief career that lasted just over two years, she worked regularly,

appearing in the United Artists’ film Electra Glide in Blue and as

a Universal Studios “contract player,” guesting on the TV series The

Six-Million-Dollar Man, Kolchak:

The Night Stalker, Get Christie Love

and in a recurring role on Lucas Tanner.

In

a brief career that lasted just over two years, she worked regularly,

appearing in the United Artists’ film Electra Glide in Blue and as

a Universal Studios “contract player,” guesting on the TV series The

Six-Million-Dollar Man, Kolchak:

The Night Stalker, Get Christie Love

and in a recurring role on Lucas Tanner.

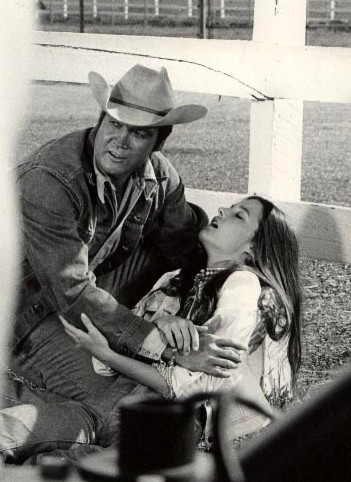

At

the beginning of 1975, Greene played the title role of Aura Lee Benton in

the classic Rockford Files episode “Aura Lee, Farewell.” It wasn’t

a huge role – her character was killed off about fifteen minutes into the

episode – but it was a substantial and memorable one. Her performance and

disappearance cast a shadow over the rest of the episode. After that,

Greene never acted again.

Thirty years later, she is a creative writing teacher contentedly living

in a lovely historic townhouse on the main drag of a small Pennsylvania

town. She is doing something she loves, “far more than acting,” she says.

She teaches women, children and teens how to tap into the creative

process, to love the art of writing, not to fear it. Her work helps

students take a break from perfectionism, trust their ideas, and reduce

tension and stress. Her business is called Write from the Heart.

“I

give my heart to people, just like an actor, except I do it in the

classroom and on the page,” she says.

Greene acknowledges that she was not ready - nor right - for the career

that she had pursued with such dedication. She was shy and deeply

uncomfortable “being watched by a camera.” She longed to live a more

contemplative life. It took her years to realize that she was stalking the

wrong talent.

“The real me is rather tender and poetic. I wasn’t ready to reveal that to

a camera, nor – do I think - would I ever have been. I was a writer – a

thinker - but, for years, I spent my energy on becoming famous. My parents

put high value on stardom, and I was up to my neck in their dream.

It’s corny - and sad - but I spent a lot of time believing how much they

would love me when they saw me up on that screen.”

Ironically, her parents were too caught up in their own Hollywood lives to

show her what roads to take, what pitfalls to avoid. Greene’s drive,

dedication and beauty was opening doors for her, but she wasn’t sure what

to do once she got inside.

“In

retrospect, I didn’t know what I was doing,” she admits. “I had a lot of

nerve and talent, but I was untrained and I was doing it all for my

parents’ love. I didn’t want to open up to a camera – there was no love

there, but I couldn’t figure out where else it might be. For me, the set

was stressful and chaotic. I was 21, and already a very private person. I

didn’t belong in front of a bunch of strangers taking in my every move.

But, God, I was hell-bent. Nobody could stop me. It’s embarrassing, but I

was naïve, I fell for the Hollywood myth. I wanted to be Katherine

Hepburn, like every other girl in the world… and I truly believed I

could get there overnight! Meanwhile, I didn’t notice that, in reality, I

was doing incredibly well for an unknown.”

“In

retrospect, I didn’t know what I was doing,” she admits. “I had a lot of

nerve and talent, but I was untrained and I was doing it all for my

parents’ love. I didn’t want to open up to a camera – there was no love

there, but I couldn’t figure out where else it might be. For me, the set

was stressful and chaotic. I was 21, and already a very private person. I

didn’t belong in front of a bunch of strangers taking in my every move.

But, God, I was hell-bent. Nobody could stop me. It’s embarrassing, but I

was naïve, I fell for the Hollywood myth. I wanted to be Katherine

Hepburn, like every other girl in the world… and I truly believed I

could get there overnight! Meanwhile, I didn’t notice that, in reality, I

was doing incredibly well for an unknown.”

Today, she makes her living opening up to the world… through her love of

writing. “I teach people to relax, focus, pay attention to the world

around them. I’m particularly interested in supporting people who are

afraid, who have always longed to write, but think they can’t. They can,

if they’re taught with compassion,” she says.

Greene’s Pennsylvania home has few signs of her long-ago Hollywood

existence. One hall is lined with 8x10 glossies from the 1940s including a

picture of a five year old Melissa sitting by a pool with Johnny Carson,

next to one of her mother, laughing with Ginger Rogers, Lucille Ball and

Ann Miller on the set of Stagedoor. Next to that, her mother smiles

broadly, wearing a sarong and seated in a thatched hut amidst a line of

chorus girls in grass skirts. Another depicts her father in Palm Springs,

circa 1945, posing next to a Cadillac in shorts, cowboy boots and a pith

helmet. Below that is an autographed publicity close-up of her father,

which he gave to her as a Christmas present when she was in her teens. “He

signed it in the ‘60s but dated it 1940,” she says, “It reads ‘To my

darling daughter, Melissa, who won’t be born for 11 years. I love you,

Dad.’” She stares at the photo. “I’m the only person with autographed

photos of my parents,” she says, shaking her head and sighing. “My father

loved a good joke.”

Her birth as a writer is also with her in the home, best symbolized in the

form of 51 journals that she has kept since she was a young girl. “My

journals were a way to survive. They saw me through everything. When I was

younger, I believed they were worthless, filled with constant complaints.

As years went on, I saw them as a fascinating record, complaints and all.

Today, they help me make sense of my life, and give me endless ideas for

my writing. Journals are as essential as food.”

Greene’s first

movie role came by accident. She worked as a tour guide at NBC Studios

in the early 1970s. Several years later, walking out of a reading at

MGM for director George Cukor, who was casting Travels with My Aunt,

she ran into casting director, Mike Fenton, in the hall. When he asked

what she was doing there, Greene replied, boldly, that she was now an

actress. He told her he was casting a film called Electra Glide in

Blue with Robert Blake, and having a problem finding the female lead

– a Radcliffe hippie.

“I remember him

saying that they’d already seen Susan Sarandon, Katherine Ross, and

Sissy Spacek, but none of them were right. I was face-to-face with my

dream – ready… or not! It was completely surreal.”

Fenton sent her to

meet the director that afternoon. “I remember, Robert Blake was in the

interview. That never happens in Hollywood,” Greene explains.

“There I was. I didn’t know how to read. The script was terrifying to

me. I knew I was staring at “the big break,” and I was frozen. Rupert

Hitzig, the director, said, ‘Oh, just throw the script away. Just look

at him. Tell him to back off.’ So I looked at Bobby, and I was suddenly

overwhelmed with anger. And since I was a writer, I began to write the

script on the spot – I started calling him names and backed him into a

wall. I remember getting angrier and angrier at him because he was

acting and I couldn’t reach him, emotionally – the real Robert

Blake. The more he avoided me, the more exciting the script was that I

was writing in my mind.”

Greene was hired for

the role. The next day, she received a conference call from seven

casting directors at United Artists.

“They told me I had

been chosen to costar in this movie. They needed my address and phone

number and my social security number, I think, which all seemed rather

odd to me at the moment. Then they told me I needed an agent… fast. It

was fabulous and frightening, and it didn’t seem real,” she says. Her

father called the head of the William Morris Agency, and she was signed

the next day.

Little did she know, the film was already steeped in problems. It had

been written and was to be directed by newcomer, Rupert Hitzig – his own

first Hollywood break. The producer was another film novice, James

William Guercio, best known as the manager of the rock group Chicago. A

total unknown in the film world, Guercio saw opportunities to control

the direction of the film, and eventually had Hitzig removed from his

own project. Hitzig never had another big break in Hollywood. Guercio

became the director, while Blake and cast struggled to make a

first-class movie controlled by an amateur. Plunked down right in the

middle of the circus was Greene.

“From the first

rehearsal reading, there was distrust and confusion. Bobby was trying

to guide Guercio. To Guercio, the movie was just another toy. So here I

was around a table on Melrose Ave. with these Hollywood veterans: Bobby

Blake, Elisha Cooke, Mitchell Ryan and Billy Greenbush, and no director,

or source of support. I didn’t know how to act, nor did I really want

to, but I didn’t know that yet. I kept looking around that table

and thinking I was supposed to be on top of the world, but the truth

was: I was scared.”

The film was shot

on location in Scottsdale, Arizona. It was an odd mix of experienced

old-timers and newcomers who had never worked on a film in their lives.

This included Greene, as well as Peter Cetera and the group Chicago,

hired by Guercio for small roles as hippies living on a commune.

“Peter Cetera

played my boyfriend. He was great – so genuine. That’s when I first

began to see the kinship between musicians and writers - a very

different relationship than I was having with the actors. I couldn’t

relate to the actors at all, but I didn’t understand why

because I was supposed to be one. I saw Peter Cetera years later,

and the first thing I did was thank him for being real.”

Legendary cameraman Conrad Hall was the cinematographer, and much of the

crew had recently worked with him on Butch Cassidy and The Sundance

Kid. There was also wardrobe designer Rita Riggs who later designed

the costumes for An Officer and a Gentleman. And photographer

Phil Stern, who had helped make legends of every major star in

Hollywood. But even their talents and experience couldn’t undo the

turmoil swirling behind the scenes of the film.

“Hollywood was

turning a corner in the early 1970s,” Greene says, “Unknowns like

Guercio were stepping into the business with money, but no experience,

hobnobbing with the best. Electra Glide was a film out of

control. The power games eclipsed everything. We were all caught up in

it. If you look at the film now, you’ll see that the first half doesn’t

look at all like the second. The first half was shot by Conrad Hall;

the second was done later by a half-ass second unit. It was a mess.”

From the first

rehearsal reading, Greene was intimidated by her temperamental co-star,

Blake. “I didn’t know how to be an actress. I was 23 and I was

sensitive and overwhelmed. The problem was: I liked Robert right

away. I wanted to know him, to

experience who he really was - but I was terrified by him. He was

erratic and intense and he was ‘on’ which overwhelmed me. Today, I

realize he was struggling, just like me.”

Of

course, in the years since, Blake’s temper has become common knowledge

when, in 2001, his wife Bonnie Bakley, was found shot to death in

Blake’s car. According to Blake, he had left her sitting alone in the

car, in front of a restaurant where they had just had dinner. Blake was

indicted for the murder but eventually found Not Guilty due to a lack of

evidence. However, the court fight and the continued doubt about his

innocence have played havoc with his career.

“We did a half-nude love scene in the front seat of a car. I think we

made-out for about ten takes. By the time we

climbed into the back, we had most of our clothes off. The crew had

fogged the windows, and I remember Bobby lying next to me in his jockey

shorts, laughing and telling me jokes to help me relax. We drew pictures

on the foggy glass with our feet. In retrospect, he understood my fear.

There were moments when he was protective and sweet, but there were

others when he became incredibly dark. The whole experience was dark,

except at moments when I made him laugh. After it ended, our lives

diverged and I never saw him again.”

When the news of the murder came forward, Greene says she was confused.

“For years, I blamed Robert for what happened to me on Electra

Glide. But, seeing him in the courtroom, I found myself thinking

more about his delicacy - his sweetness - than his volatility. In my

heart, I still can’t link him to the crime. Whatever happened, he was a

sitting duck, because he’s known to be moody - he plays those

characters. But he wears a mask. It’s understandable; he was abandoned

as a child. He was lonely during Electra Glide, and I felt

compassion for him, because he seemed like someone who’d been thrown

into too large a world at a young age – like me. Whatever the truth is,

he’s suffered, and I feel deeply sorry for him.”

Greene got her first lesson in the cruelty of Hollywood when, months

after shooting ended, she went to the preview screening of Electra

Glide in Blue. Sitting in the back of the dark theatre, she

realized that she had been edited out: from female lead to two lines.

To add insult to injury, her name was misspelled in the credits.

“I

was devastated,” she says. “That’s a story in itself. But Hollywood rolls

right on. Suddenly, my agents were very hard to get on the phone.”

Nevertheless, she pressed on. In 1973, she interviewed at Samuel Goldwyn

Studios with writer/director, Michael Cimino - winner of the Academy Award

for Best Picture for The Deer Hunter, and also the man behind the

legendary flop, Heaven’s Gate. Cimino was directing the Clint

Eastwood movie Thunderbolt and Lightfoot and needed an actress who

could also ride a motorcycle in one scene. ‘Nooo problem,’ I told him…

though I’d never been on a motorcycle in my life!” Greene says.

She convinced Cimino to meet her on the back lot in two weeks, then called

stunt-man friend Bud Ekins, for lessons. Ekins was Steve McQueen’s double

in The Great Escape and stunt coordinator for Electra Glide in

Blue. Within weeks, Greene could handle both a Honda and a Harley.

When she and Cimino met, two weeks later, she rode like a pro. Cimino was

impressed.

“But, before he’d give me the part, he asked me to ride up the hill and

back down, one more time,” Greene remembers. “I was so overstimulated. I

came down the hill, and forgot where the brake was. I crashed into a pile

of steel dollies, and broke both bones out of my lower leg. Bud Ekins laid

across me while they cut my boot off. After surgery, that day, I looked up

and the nurse asked me if I knew Clint Eastwood. It was crazy. I was in a

cast for five months.”

When

the cast came off, she hit the streets again. Again, she got lucky. Her

promotional savvy landed her a contract with Universal Studios, and

secured her a place in the dying tradition of old Hollywood: the studio

system. In the 1930s and 40s, MGM, Warner Brothers and 20th

Century Fox kept a stable of actors and actresses under standard seven

year contracts. They worked exclusively on that studio’s films, while

being “groomed” for stardom. By the 70s, this kind of agreement was

becoming outdated, but Greene was one of the last actors to sign such a

deal, along with Lindsay Wagner, Randy Mantooth, Susan St. James and

Harrison Ford.

When

the cast came off, she hit the streets again. Again, she got lucky. Her

promotional savvy landed her a contract with Universal Studios, and

secured her a place in the dying tradition of old Hollywood: the studio

system. In the 1930s and 40s, MGM, Warner Brothers and 20th

Century Fox kept a stable of actors and actresses under standard seven

year contracts. They worked exclusively on that studio’s films, while

being “groomed” for stardom. By the 70s, this kind of agreement was

becoming outdated, but Greene was one of the last actors to sign such a

deal, along with Lindsay Wagner, Randy Mantooth, Susan St. James and

Harrison Ford.

“I

talked my way into a reading for Monique James, the head of Universal’s

New Talent Department. Those were the days when actors actually read

for producers, before producer’s required a video of the actor’s work,

beforehand. I remember the scene I chose. It was extremely funny, and the

casting director wrote a little note ‘could do comedy very well.’” Greene

still feels that she would have been better suited as a comic than a

serious actress, “but because I looked like I did, that’s not what they

hired me for. I had to be a face. I had to be sexy. Which – thankfully and

quite consciously, I may add – was not in my job description when I

created Write from the Heart!” she laughs.

Greene’s first role with Universal was the lead guest starring role of an

episode of the then red-hot series The Six Million Dollar Man with

Lee Majors. Greene knew the producer Harve Bennett, who went on to produce

several of the Star Trek movies. Bennett had campaigned for her

studio contract. “I had a way of getting people riled up - I think I was

Mickey Rooney in a former life: ‘Hey, let’s have a show!’ At that time,

enthusiasm went over really big in Hollywood. That’s how my father made it

into RKO. In those days, if you had a head of steam and a lot of guts –

boy - you could get far.”

Bennett

was so excited about her prospects that he sent her a telegram that read:

“Good luck! I’d say ‘break a leg,’ but you just might do it!” and then

gave her a bigger screen credit than star Lee Majors. She remembers

feeling overwhelmed by the pressure.

“I

didn’t know what I was doing, pure and simple. And I was scared to death

of failing. Lee Majors was great. I’ll never forget him taking me by the

shoulders and moving me out of the way for his close-ups. Contrary

to my dream, I didn’t exactly shine. At the screening, Harve said, ‘You

didn’t have too much fun doing that, did you?’ which has always haunted

me. Afterwards, all I remember my father saying was ‘You looked nervous.’

And my grandmother writing me this note from Miami that said ‘Darling, you

were wonderful, but… next time, speak up!’ I didn’t look at the show for

30 years.”

Still,

she kept plugging away, appearing in six Universal series in under a

year: the lead female guest star in an episode of Get Christie Love

with Teresa Graves, a recurring role in two episodes of Lucas

Tanner (starring future Good Morning

America host

David Hartman), and a small part on Kolchak: the Night Stalker with

Darren McGavin. She even had the opportunity for her own series – a show

about Canadian Mounties in which she screen tested with a then

mostly-unknown carpenter-turned-actor named Harrison Ford and Randy

Mantooth, who had just starred in the popular but short-lived series

Emergency! The series never made it on the air.

Still,

she kept plugging away, appearing in six Universal series in under a

year: the lead female guest star in an episode of Get Christie Love

with Teresa Graves, a recurring role in two episodes of Lucas

Tanner (starring future Good Morning

America host

David Hartman), and a small part on Kolchak: the Night Stalker with

Darren McGavin. She even had the opportunity for her own series – a show

about Canadian Mounties in which she screen tested with a then

mostly-unknown carpenter-turned-actor named Harrison Ford and Randy

Mantooth, who had just starred in the popular but short-lived series

Emergency! The series never made it on the air.

By

the time she got the Rockford Files role, Greene was starting to

reconsider her career. “I approached everything with a writer’s mind, and

that was death, because I was watching the scene I was in, not

living it - analyzing it in my mind, instead of really being there. I

wasn’t an actress, I was writing a script for an actress.”

Nevertheless, her Rockford Files episode was a success, and she

remembers the experience fondly. “Rockford was the most successful

thing I did. First of all, I was playing a poetic - and sensitive - free

spirit. No wonder I was at home!” she laughs. “It’s interesting that the

show was directed by one of Hollywood’s greatest child stars, Jackie

Cooper. He was tough, but he was also

rock-bottom sure – totally

confident. Jackie was lying in the back seat of the car during my scene

after Robert Webber picks me up, hitchhiking. The camera was on the side

of the car. So it was just the three of us there – not a whole crew - and

I was able to relax.”

rock-bottom sure – totally

confident. Jackie was lying in the back seat of the car during my scene

after Robert Webber picks me up, hitchhiking. The camera was on the side

of the car. So it was just the three of us there – not a whole crew - and

I was able to relax.”

“The

scene where we hit the man in the road at night? I kind of liked myself in

that scene - I really looked scared. But scared was kind of

easy for me, you know!” she laughs. “There’s also a scene that I love:

we’ve hit the man,

and

we stop at this shack for Robert to make a phone call for help. He’s

dialing the phone frantically. We’ve just spent the night together, and I

look at him and realize it was just another fling. There’s a sadness and

depth in my eyes… a whole lot more in that look than you usually see in an

Universal TV show. It was the first time I saw the true me, onscreen. I’m

still proud of it.”

More roles came her way. However, by this time, Greene had had enough. She

decided that perhaps acting wasn’t for her after all. “The problem was I

didn’t believe in myself, because I wasn’t

being myself. I thought I’d find love, that people would see me on

the screen and be amazed. I now realize that I wanted them to see the

person I’ve become all these

years later. Anyone

will tell you now; I’m a very gentle, private person who doesn’t like to

be onstage. In retrospect, I think a few people at Universal got a glimpse

of the real me – Harve Bennett, Billy Wilder, Dick Levinson who produced

Murder She Wrote. They were highly intelligent, wonderful

people – writers themselves - and they recognized my intellectual spark.

But supportive friends and big breaks mean nothing unless you love

what you’re doing.”

When she finally made the decision to leave the business, she simply

stopped going on interviews, and eventually cancelled her contract with

William Morris. “It was clear,” she says, “I was having dreams that the

studio was in flames. I was in agony trying to be someone I wasn’t.”

For awhile, Greene went into modeling. In the mid 1970s, she broke into

advertising copywriting and

worked for Campbell

Ewald Advertising, in Detroit. She returned to Los Angeles to write and

produce Previews of Coming Attractions for the movies.

In

1980, she married a paintings conservator and moved east to Boston,

then to Williamstown, Massachusetts, where her husband worked at The

Sterling & Francine Clark Art Museum. It was a shock to go from Hollywood

glitz to a more sedate academic lifestyle, but Greene soon felt at home.

“It was like food for the starved. It was a huge opening to a world that I

wish I’d had more of, before Hollywood struck. I started writing serious

short stories, connected with faculty at Williams College, and luckily met

Jim Shepard, a fiction and film professor. He was the first person to

recognize my gift, to read my stories and urge me to keep writing. He

recommended my work to The New Yorker and The Atlantic

Monthly, and we’re friends to this day. Jim was funny and

compassionate in the classroom, and his teaching style inspired my own.”

Greene wrote fiction, full-time, for several years, and continued her

journals, in earnest. In 1983, her first published short story appeared in

The Northwest Review, a literary journal from the University of

Oregon, and her poetry was also published.

During those years, she also began a serious songwriting collaboration

with pianist, arranger and composer, Lincoln Mayorga. Greene and Mayorga

met in 1970 when she was a tour guide at NBC and he was playing piano in

the orchestra on The Andy Williams Show. Mayorga moved East in the

early 90s, and the two became reacquainted after twenty years. They wrote

steadily together for five years for the sheer joy of it. Their songs were

performed by Michael Feinstein and Andrea Marcovicci, and recorded by a

group of Hollywood’s most illustrious back-up singers, The Power of Seven.

“It was one of the happiest, most creative five years of my life. Lincoln

and I were a force, because we were creating for ourselves, and nobody

else. We were doing it for love, not fame, and this was a revelation to

me, a real change in my values. We tapped into a certain truth.”

At

the same time, she began a quiet but highly personal endeavor: teaching

creative writing to senior citizens, with a particular interest in helping

even the most crippled to flower. “I didn’t know it, but I’d cracked the

door open to my future,” she says.

Meanwhile, Greene’s marriage came to an end. And so did the writing “…for

about six years of grueling, non-stop survival.”

Over the next six years, she went into partnership with a well-known

Americana and

Folk Art Antiques dealer. Using his knowledge and her promotional

abilities, they built a million dollar business in a restored 19th

century church in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. The business came to an

abrupt end in 2000 when her partner suddenly left – “A precipice I would

not recommend looking over, if you can help it,” she says - and Greene

decided to move to Pennsylvania to reinvent herself, once again.

“I

was visiting a friend, and I walked down this street and saw this

beautiful house, and it was sort of like; okay, get everybody away from

me. I don’t want restaurants. I don’t want clothes. I don’t want to worry

about what I’m looking like. I just want to move here and be quiet and get

back to my writing. It was a leap of faith.”

To

make ends meet, she took a job in an office park. “I took a corporate job

for two months, writing business newsletters. It almost killed me. While I

was there, 9/11 hit. I remember I was in the conference room. I watched

those planes tear into those buildings, and… I looked around me… and I was

surrounded by strangers, in a strange job, in this totally strange town

outside Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and – a few days after that - I was

driving home, and I heard this

little voice in me

whisper, ‘Melissa, you’re a poet.’ I quit the job, and I was suddenly out

of work in this huge house, all alone. A few weeks later I remembered one

of the dear ladies in the nursing home, back in the 80s, and I had this

vision to teach writing, but to teach it from the gut, with empathy and

compassion.”

Her vision was Write from the Heart, a series of creative writing

workshops for women, children, teens, which she began in 2001 with a group

of 15 women. She has since taught hundreds. “Suddenly, my dream became

clear,” she says, “to open people’s hearts, to help them discover the joys

of writing, without being afraid. To help them over the same

self-consciousness that I’d felt while being scrutinized by a camera.”

Today, she offers year-round classes for women, as well as weekly workshops

and summer camps for children and teens. Her classes draw students from as

far away as Boston and Washington D.C. They range from young adults to

senior citizens; business women and homemakers. She also works in

conjunction with a hospice grief program, local schools, and therapy

counseling groups.

“Creative writing is a therapeutic tool. It can console, illuminate, and

heal. It can also be one hell of a lot of fun! My goal is: to teach a few

simple writing basics in an atmosphere of integrity, kindness and warmth.

Oh, yes, and we laugh a lot! I try to create a safe, gentle place where

women can be themselves. Even during my acting days, I was fascinated with

touching people’s feelings… but with understatement and subtlety. Part of

my problem was: Hollywood didn’t value subtlety, nor did it value decency

and respect. I was living in duplicity and glitz, but I always kept

my eye on decency and respect.”

Because of the years that she was distracted from

her own writing career, she is particularly interested in

“reacquainting”

women with their creativity, especially those who

have put their writing lives on pause because of divorce, children, or

career.

Because of the years that she was distracted from

her own writing career, she is particularly interested in

“reacquainting”

women with their creativity, especially those who

have put their writing lives on pause because of divorce, children, or

career.

“My goal has been to help women slow down, take a

breath, and find a deeper understanding of their lives and writing.

Everyone has an imagination. They may just not know how to get in touch

with it… or they may have simply been pointed in the wrong direction.”

Her students come from all over to enjoy her

insights, compassion, and wit. “What I do is hard to describe. Mischief

helps. Also irreverence. One thing I do: I share objects with people -

things that turn my senses on - because writing is all about the senses: what things smell, taste, feel and

sound like. I bring in feathers to touch, and fish food to smell, and

these little miniature hangers that bring out the most amazing stories in

people that, half the time, have nothing to do with miniature hangers!”

She laughs. “And – voila! – suddenly, we’re writing! But the key word is

compassion.”

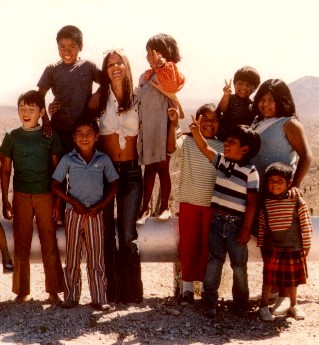

Now,

more than thirty years after her short-lived quest for Hollywood glory,

Melissa Greene shows two pictures. One of them as a young woman on the

set of Electra Glide in Blue, standing in the middle of a group of

Mexican schoolchildren who were extras in the film. The second shows her

today, surrounded

by children from one of her summer camps. Three decades of experience  have

definitely made some changes, but what is most striking is how little -

really - has changed. Melissa Greene has come a long way to end up in a

surprisingly similar place – one of excitement,

beauty and creativity - but a place far more comfortable than Hollywood: a

peaceful place within her own heart.

have

definitely made some changes, but what is most striking is how little -

really - has changed. Melissa Greene has come a long way to end up in a

surprisingly similar place – one of excitement,

beauty and creativity - but a place far more comfortable than Hollywood: a

peaceful place within her own heart.

“I

don’t think it’s a coincidence I found my way back to a small town,”

Greene says. “I grew up in Encino, California, which was a small town in

the 1950s, before it became the brunt of suburban jokes. The Pennsylvania

countryside reminds me of the Valley, when the land was still pure, though

the culture here is the complete opposite. That’s what I needed though. I

needed to see the real world, going about its daily business, the world

I’d missed.

“In essence, I came here to heal. And Write from the Heart was born from,

and during, that period of healing. I wanted to use my grief from being

separated from my writing… and myself… to help others. In the

process, I’ve become whole.”

And so, Greene has accomplished at least part of her happy ending. She

is happy to be hard at work

making her workshops a safe haven for writers. “This is the class that I,

personally, would have wanted to go to all those years back. Hey, but

since I teach it, I guess I get to go to it now,” she

laughs, “so, you see, we’re all benefiting!”

She is also working on her memoir. “Gee, I wonder what it’s about?!” she

smiles.

Most of the people in Greene’s world know little about her Hollywood past,

though this seems to be changing. “I’ve just never talked about it. First

of all – I mean - you don’t just sit down in front of your friends and

say, ‘Hey, you know what? I was on The Rockford Files,’” she

quips. “Though, lately, I’ve become looser about it. Sometimes, I’ll free

write in class about my parents, which can

lead to everything from a description of my mother’s cigarette holder to

my father singing ‘Stars Fell on Alabama’ at the top of his lungs at 12:00

a.m. on a school night. My Hollywood upbringing is obviously a huge

subject for me. And that’s exactly what I teach people to find: their

own deepest, most important subject, that one topic that they - truly,

deep down - want to write about.”

When asked how she feels about life-after-Hollywood, Greene grows wistful.

“I’ve always wondered what those years were about. Yet, without them, I

might not have explored my creative potential. They set a tone for my

creative life, a standard I’m still reaching for. And if it hadn’t been

for my Universal days, I also wouldn’t have known how to market myself,

which has helped me to create and sustain Write from the Heart. Though,

let me tell you: it’s

much easier to market someone you love, than someone you don’t!”

she smiles.

Then

she becomes reflective again. “Looking back, I was young, and knew nothing

but Hollywood, and I kept looking

over the tops of my deepest dreams, wanting more and more. That’s what

Hollywood does: it promises you everything - too much - until

you’re glutted with fantasy and bravado and a perverse sense of

entitlement. And you’re totally blinded, spiritually. I thought the answer

was somewhere outside myself - can you believe it? And on TV, of

all places! I didn’t realize that I was more than just a face, or that my

dream was within reach, right here inside me. I couldn’t see that I would,

ultimately, flower from humility, not glamour. I didn’t know it,

but what I really longed for was to bring out the truth and soul in

people. I see a bit of that longing in my eyes, during that last scene in

The Rockford Files, the one when

I take a last look at Robert Webber. That look is worth a million dollars

to me now; a little reminder that ‘I’ was there all the time.”

Then

she becomes reflective again. “Looking back, I was young, and knew nothing

but Hollywood, and I kept looking

over the tops of my deepest dreams, wanting more and more. That’s what

Hollywood does: it promises you everything - too much - until

you’re glutted with fantasy and bravado and a perverse sense of

entitlement. And you’re totally blinded, spiritually. I thought the answer

was somewhere outside myself - can you believe it? And on TV, of

all places! I didn’t realize that I was more than just a face, or that my

dream was within reach, right here inside me. I couldn’t see that I would,

ultimately, flower from humility, not glamour. I didn’t know it,

but what I really longed for was to bring out the truth and soul in

people. I see a bit of that longing in my eyes, during that last scene in

The Rockford Files, the one when

I take a last look at Robert Webber. That look is worth a million dollars

to me now; a little reminder that ‘I’ was there all the time.”

She ponders this, then smiles. “I keep this little haiku on my desk. I’ve

carried it with me since I was twenty years old. It reads “In my dark

winter / lying ill / at last I ask

/ how fares my neighbor?” I’m proud to

have lived an unusual life. I‘m proud to have wandered off the beaten

path. But I’m proudest of creating my own path: guiding people

who are lost, lonely and creatively blocked toward freer, happier lives.

All my life I wanted to touch people - to draw them out of themselves with

humor and warmth, to make an intimate connection. And here I am – far

beyond Hollywood, in

this sweet little town in Pennsylvania - living my dream.”

For more information on

Melissa Greene and Write from the Heart, please visit

www.writefromtheheart.us