PopEntertainment.com > Miscellaneous >

Blame In on the Melisma

Blame

It on the Melisma

Blame

It on the Melisma

By Mark Mussari

In

the late 1500s Pope Gregory the XIII decided enough was enough. Gregory

believed that the melodies of the Gregorian chant, the musical mainstay of

the Catholic Church’s mass, had become corrupted. Singers were singing more

than one note for each syllable of the chant—a vocal technique known as

melisma—and the pope wanted to put a stop to it.

Gregory ordered church officials to banish all use of melisma from the

singing of Gregorian chants. The pope ultimately failed in his attempt, and

by the late 1800s the Catholic Church had rejected all of his changes.

Still old Gregory the XIII may have been on to something.

Living proof that the pope was fighting a losing battle with melisma can be

found in the angelic voiced Aaron Neville, who hasn’t met a note he can’t

bend, trill or alter with his mellifluous tenor. It takes a singer of

Neville’s range and control,

however, to pull off all this vocal maneuvering.

The

effect of melisma on contemporary singing is undeniable, and one need look

no further than American Idol

to realize its often deleterious effects. Each week the contestants

attack a new song with the vengeance of a threa tened

mountain lion.

tened

mountain lion.

The

nascent singers, almost all of whom are younger than the songs they sing,

run the gamut from

pseudo-soulful

to pseudo-country—but they all share one thing in common: their

performances have replaced the drama of emoting

with unbearable over-singing, heavily reliant on melisma. We no longer

listen to lyrics, because the singer’s histrionics are now the sole focus of

attention.

The

progenitors of melodramatic pop singing are Aretha Franklin and Stevie

Wonder. In their heyday Franklin and Wonder, possessed of incredible ranges

and vocal control, could soar around notes, rip through lines and transform

even the most mundane lyrics into human drama. Both were also musicians

(many forget that Franklin is an accomplished pianist), and their inherent

musical knowledge often protected them from straying too far from the note.

In

other words, to quote American Idol judge Randy Jackson, they were

rarely “pitchy.” Unfortunately many who have followed Franklin and Wonder lack both the vocal dexterity and the musical

knowledge to pull off either the dynamism or melisma of those two

powerhouses.

Today’s musicians refer to melisma as “runs,” those trilling embellishments,

favored by hip-hop artists, in which the singer dances all around

the actual note. Struggling to do more than their voices are capable of

doing, most of these singers end up singing flat. As Jackson would say to

his Idol wannabes: “You didn’t make your runs, dawg.”

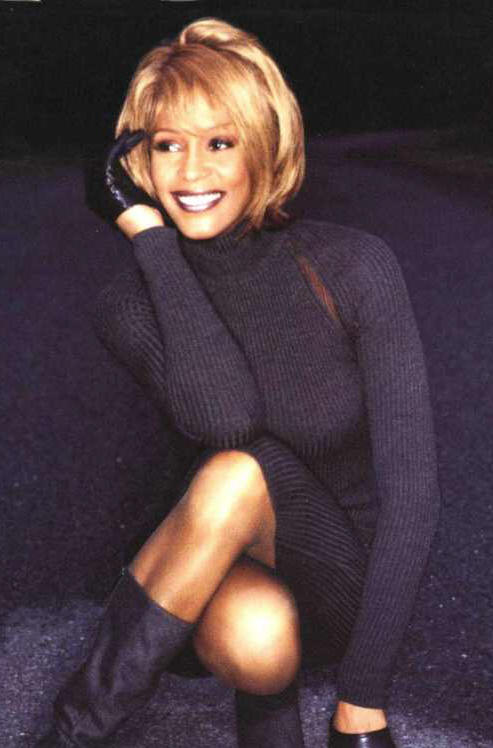

By

the time Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey, the templates for today’s

bombastic female singers, came on the scene, another cultural phenomenon had

taken place. The song became simply a vehicle for the singer to flex

her vocal muscles. The lyrics, once the

reason for singing, began to wane as Houston and Carey—and most who have

followed them—moved the attention onto their vocal maneuvers.

By

the time Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey, the templates for today’s

bombastic female singers, came on the scene, another cultural phenomenon had

taken place. The song became simply a vehicle for the singer to flex

her vocal muscles. The lyrics, once the

reason for singing, began to wane as Houston and Carey—and most who have

followed them—moved the attention onto their vocal maneuvers.

There’s a great irony to this development, clearly evident in the young

American Idol hopefuls. In their attempts to prove they are “great”

singers, they are oddly void of relating any real emotion. The song’s

meaning, located in that intricate dance between words and music, becomes

lost in the shuffle.

Watching “American Idol,” you are rarely moved or touched by anyone’s

performance, no matter how impressive, because no one seems actually to feel

anything. The singers have become disassociated from the very words they

are singing. A recent New York Times article even lamented the

increasing influence of this approach on Broadway singing.

By

over-singing and rendering the song irrelevant, contemporary singers are

unwittingly contributing to the disposability of popular music. Sadly

enough the singers, thanks in great part to too much melisma, are killing

the song.