My mother has been having

nightmares about Malcolm McDowell for years.

It’s not his fault really; he was

just doing his job to the best of his ability.

It all started in 1971 when my

stepfather took her to see the buzzed-about new film A Clockwork

Orange, the latest movie by legendary director Stanley Kubrick (2001:

A Space Odyssey, Dr. Strangelove). My mother, who has never

been good with violence, was completely freaked out by the film – an

extremely dark comedy with some brutal sections.

Nearly 40 years later, A

Clockwork Orange is considered a classic and its mood of extreme

sexual and violent anarchy – which were at the time of release was

extremely controversial – has been put into a different context by

generations of moviegoers.

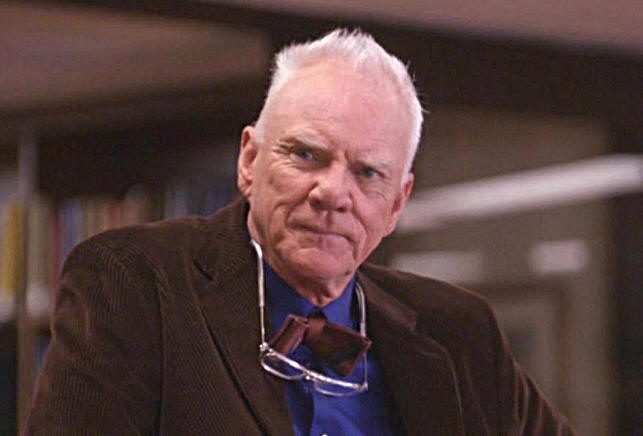

McDowell is still an acclaimed

actor with several projects in the hopper – including the new

independent drama Pound of Flesh, a recurring role on the hip

HBO comedy Entourage, an upcoming TNT series called

Franklin & Bash and a supporting role

as the school principal in the popular recent comedy Easy

A. Still, he thinks it is pretty amazing to have been part of

an iconic film which excited such passions, positive and negative,

in people.

“Oh it was great,” McDowell says.

“It was great, because really, the truth is, if you see the movie

now with an audience, they react to the film that we made – which

was a very black comedy. That’s exactly what it was. I knew we

were making this comedy, a very black comedy, but still a comedy.

The fact is if you’re beating a guy and raping his wife to ‘Singing

in the Rain’ – it is obviously [being facetious].

“I was rather shocked initially,

because everybody took it rather seriously,” McDowell continues.

“There were write-ups in the editorials of the newspapers – The

New York Times and everything – accusing us of being

pro-violence in society and encouraging it and all kinds of

nonsense. Filmmakers really just reflect what’s going on in society

and I think Kubrick did that very well. But the truth is, it was a

black comedy and now audiences love it. They laugh and they do

everything I expected them to do 40 years ago.”

Sometimes it takes a while for the

world to catch on to what Malcolm McDowell knew all along.

Sometimes it takes a while for the

world to catch on to what Malcolm McDowell knew all along.

“It’s one of the films that you’ve

got to see,” McDowell says. “Get it on a BluRay and just have a

great evening. It’s an unbelievable film.”

Actually, A Clockwork Orange

was just one of a trio of masterpieces with which a young

McDowell exploded into film consciousness in London in the early 60s

and 70s. McDowell was a huge part of the late 60s film explosion in

England – a scene that also spawned Michael Caine, Peter O’Toole,

Richard Harris, Robert Shaw and more.

However, despite the talent of the

new school of British actors, McDowell has always aspired to a

long-term career more like one of the old masters of British

cinema.

“Well, you always presume you will

be [acting for many years],” McDowell says, “because acting in

England is a profession and like a doctor or whatever you feel that

you’ll do it until the day you drop. So, I presumed, but of course

there are a lot of big pitfalls on the way to a long career. My

hero, in terms of longevity and the way he conducted himself was

John Gielgud. John really changed with the generations and managed

to adapt his style. He never went out of style, really. He was

amazing. And he learned late in life how to be a really powerful

film actor. He always thought that he wouldn’t be a very good film

actor, but it’s actually not true. When he was in his 60s he

delivered some extraordinary performances on film.”

At that point, between the films,

the British Invasion in music and the trends in art and fashion,

London was the place to be and be seen. McDowell was out of

the gate running when he made his film debut in director Lindsay

Anderson’s classic drama If. McDowell knew he was part of

something special and he was going to live his dream to the

fullest.

At that point, between the films,

the British Invasion in music and the trends in art and fashion,

London was the place to be and be seen. McDowell was out of

the gate running when he made his film debut in director Lindsay

Anderson’s classic drama If. McDowell knew he was part of

something special and he was going to live his dream to the

fullest.

“It was amazing,” McDowell

recalls. “We were making these classic movies. Michael [Caine]

made his great share of them – my God; he made some extraordinary

movies in that time. I’m thinking of Alfie and The

Icpress File and things like that. And Get Carter was a

brilliant movie. [For me] to make If, A Clockwork Orange and

O, Lucky Man! – it came out of the gate rather fast.

They were the movies of their time and they were great pieces

of… not only box office, but they were artistic triumphs,

certainly. So, you’ve got both – the hit with the art movie. So

that was great. That was a terrific thing to get.”

It all came back to director

Anderson, with whom McDowell quickly developed a rapport, starring

not only in If, but also in the director’s films O, Lucky

Man! and Britannia Hospital.

“He was the enfant terrible

of his generation of directors,” McDowell says, “an extraordinary

talent, one of great, great geniuses of his time, really. He was a

theater director primarily. His film work, I suppose is rather

meager compared with the talent. He didn’t make that many movies,

but when he made them, my God, they were unbelievable. I was lucky

enough to be cast by him in my first movie If, which was

about a revolution in a boy’s school. It’s a fantastic film and

holds up very well today. It has not dated at all. It’s one of the

classics of British cinema. I was lucky enough to be chosen by

him. I went to an audition and he picked me out, so I was just

very, very lucky, because I had done loads of auditions before and

I’d always got to it’s either me or somebody else – and it was

always somebody else who got it. So, I was very lucky, this time it

was my turn. The thing was: I got a masterpiece. It could have

been a Hammer Horror film, but it wasn’t, it was one of the great

movies ever made in England.”

It was the performance in If

that put McDowell on Kubrick’s radar for the starring role in

A Clockwork Orange. The director was so impressed by

McDowell’s work that he didn’t even have to audition for the role.

In fact, McDowell recalls, he was essentially cast with a phone

call. Kubrick was notorious as a director for his perfectionism and

his occasional prickliness – his Paths of Glory and

Spartacus star Kirk Douglas famously called Kubrick “a talented

shit” – however McDowell enjoyed working with the man. McDowell

does acknowledge it was a very dissimilar type of set than he had

experienced with Anderson.

“Kubrick was a very different type

to Lindsay Anderson, who was very emotional, irascible and didn’t

suffer fools lightly,” McDowell recalls. “Stanley was very

self-contained, very quiet, very measured. Completely the opposite,

really, but still extraordinary in his appetite and enthusiasm for

everything connected with movies. It was amazing. He was a

fantastic guy, really – and, of course, made some of the greatest

films that have ever been seen on the big screen.”

“Kubrick was a very different type

to Lindsay Anderson, who was very emotional, irascible and didn’t

suffer fools lightly,” McDowell recalls. “Stanley was very

self-contained, very quiet, very measured. Completely the opposite,

really, but still extraordinary in his appetite and enthusiasm for

everything connected with movies. It was amazing. He was a

fantastic guy, really – and, of course, made some of the greatest

films that have ever been seen on the big screen.”

By the mid-70s, McDowell was on

top of the acting world. And then the British cinematic tradition

pretty much ground to a halt.

“Everything changed,” McDowell

recalls. “The Arabs put up the price of oil. Every American

producer in London upped his stakes and moved to California and that

was the end of it, because without the American producers there, the

English were not very good at putting things together and raising

money and wheeling and dealing, which the Americans of course were

geniuses at. So the film industry as we knew it completely

disappeared. Of course they made movies there. They made the Bonds

and things like that, but that’s not really what we’re talking

about. They could be made anywhere. They’re basically American,

anyway.”

Therefore, McDowell did what any

reasonable actor would, what most of his contemporaries did, what

even John Gielgud ended up doing – he went to Hollywood.

McDowell’s first American film

released – he actually did Bob Guccione’s infamous Caligula

first, but it was not let loose on cinemas until later – was a sweet

and intriguing science fiction film called Time After Time

(1979), which speculated what would happen if

pioneering sci fi writer H.G. Wells had

actually created a time machine and was forced to go into the

future in search of Jack the Ripper. The film was a bit of a box

office disappointment at the time of its release, but in the years

since it has grown a strong cult following.

“It was delightful,” McDowell

says. “I fell in love with my leading lady [Mary Steenburgen] and

we got married. We had two children. It was a fantastic shoot to

be in one of the most beautiful cities in the world – San Francisco

– playing this lovely character who is a whimsical person. H.G.

Wells, the great socialist of the Edwardian era, who actually meets

a modern, liberated woman and is completely befuddled by it. He

doesn’t understand it at all. All the modern inventions, which, of

course, some of them he foresaw – it’s fun seeing modern life

through his eyes. It’s a very charming film and I’m very fond of

it. I’m very fond of the character I played. And also, he’s not a

heavy… They never offer me these parts, though I’m playing one now

on television – a renaissance man. It was fun for me to change up,

because I think the movie I’d done before was Caligula, so

coming from that to this lovely film, it was a lovely change of

pace. I really enjoyed it.”

McDowell has never looked back,

taking on a wide variety of roles in film – from big-budget

blockbusters (Blue Thunder, Cat People) to genre films

(Star Trek: Generations, Tank Girl, the recent Halloween

remakes) to smaller independent films (Night Train to Venice,

Bopha!, Red Roses and Petrol) to comedies (Get Crazy, Milk

Money, In Good Company, Easy A). He has also been a significant

presence on television, starring or recurring on series such as the

late 90s remake of Fantasy Island, Pearl (Rhea Perlman’s

post-Cheers sitcom), The Mentalist, Phineas

& Ferb

and Entourage.

McDowell has never looked back,

taking on a wide variety of roles in film – from big-budget

blockbusters (Blue Thunder, Cat People) to genre films

(Star Trek: Generations, Tank Girl, the recent Halloween

remakes) to smaller independent films (Night Train to Venice,

Bopha!, Red Roses and Petrol) to comedies (Get Crazy, Milk

Money, In Good Company, Easy A). He has also been a significant

presence on television, starring or recurring on series such as the

late 90s remake of Fantasy Island, Pearl (Rhea Perlman’s

post-Cheers sitcom), The Mentalist, Phineas

& Ferb

and Entourage.

Though he is best known for

dramatic roles, McDowell enjoys comedy and feels it suffuses all his

parts.

“I am known for the dramatic

stuff, but you know if you look at it, really closely, I always go

for the comedic, even if I’m playing a serial killer,” McDowell

says. “I’ve always tried to find the comic moments whatever the part

– obviously not if it’s obviously something very serious – but I

always try to look for not a laugh, but a smile or something,

something to engage the audience.”

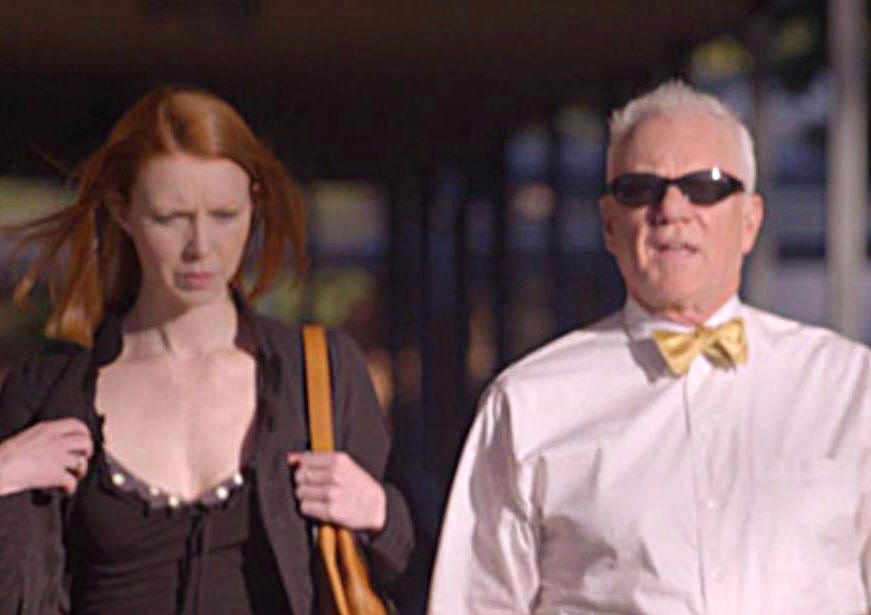

Perhaps his best-known comic role

has been one of his most recent ones, the recurring character of an

aging Hollywood talent agency head on the popular HBO series

Entourage.

“That’s a great show and of

course, it’s brilliantly written,” McDowell says. “Doug Ellin is an

amazing writer and has managed to keep the standards… through eight

seasons I think it’s pretty remarkable, of course like

anything on television it’s uneven, but he’s managed to keep it

really good from season to season. I love doing it. I love the

character. It’s fun. It’s always fun sparring with Jeremy Piven.

That was fun.”

McDowell is also going to star in

an upcoming series comedy/drama series with Breckin Meyer and

Mark-Paul Gosselaar for TNT called Franklin & Bash.

“That’s a terrific show. It’s

about a law firm in LA and I’m the sort of a renaissance man who is

the head of it – and rather an eccentric character who is lovely and

hires these two thirty-somethings to come in and give the law firm a

kind of thinking outside the box, because they are sort of ambulance

chasers. It’s great.”

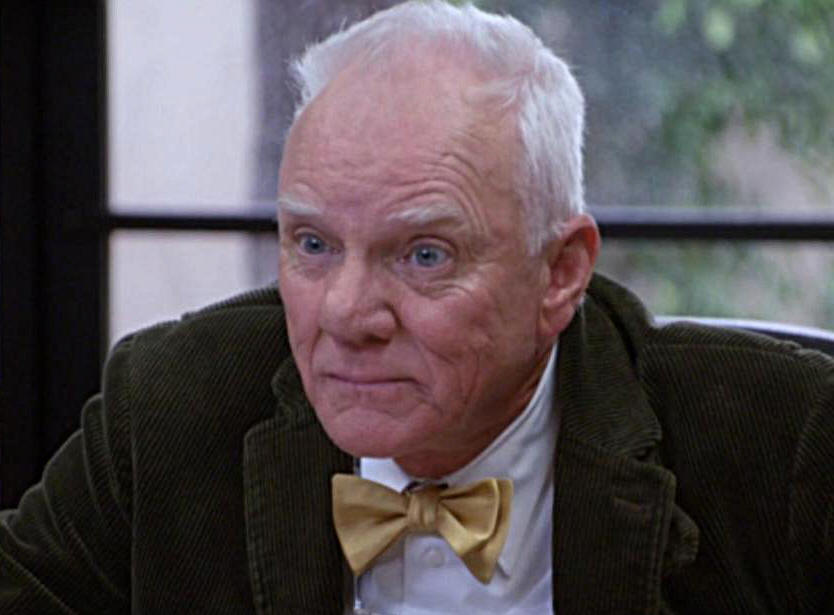

He is also starring in the

independent drama Pound of Flesh as a popular college

Shakespeare professor who gets into trouble when he sets up a

service where his attractive young students “date” local businessmen

in exchange for getting their tuition paid off. The film also stars

film vets Timothy Bottoms (The Paper Chase), Dee Wallace

(ET-The Extraterrestrial) and upcoming actress Whitney Able

(Monsters).

He is also starring in the

independent drama Pound of Flesh as a popular college

Shakespeare professor who gets into trouble when he sets up a

service where his attractive young students “date” local businessmen

in exchange for getting their tuition paid off. The film also stars

film vets Timothy Bottoms (The Paper Chase), Dee Wallace

(ET-The Extraterrestrial) and upcoming actress Whitney Able

(Monsters).

The role – based on a true story –

was written for McDowell by writer/director Tamar Simon Hoffs, who

had also directed McDowell in the film Red Roses and Petrol.

Hoffs has been on the fringes of the Hollywood scene for years – she

is probably best known for writing the Tony Curtis film Lepke

(1974) and writing and directing The Allnighter

(1987), the film

debut of her daughter, 80s rock star Susanna Hoffs of the Bangles.

McDowell has been lucky enough to

work with some of the great directors in film history: beyond

Anderson and Kubrick he has worked with the likes of Richard Lester,

Nicholas Meyer, John Badham, Richard Benjamin and others. Still, he

enjoys the passion of less-well-known directors like Hoffs.

“Well, everybody’s got to start

somewhere, however talented,” McDowell reasons. “I’ve been lucky,

I’ve worked with some great ones and we go through the whole

spectrum. A lot of first time directors I enjoy. The thing is, of

course I’ve been around a long time and obviously I’ve picked up

quite a lot, but the thing is if you’re working with a young

director or new director is not to make them feel intimidated and to

listen to what they have to say, because actually you really want to

be directed. You really do want help. Of course I can do it on my

own, but I’m always open to suggestions. So it’s fun working with

new directors. And of course, working with established and

well-known directors is also fun, because you know whatever you do;

they are going to make you look twice as good.”

McDowell had enjoyed working with

Hoffs on Red Roses and Petrol and enjoyed the experience, so

he was happy to sign on when she came to him with another idea –

which became Pound of Flesh.

McDowell had enjoyed working with

Hoffs on Red Roses and Petrol and enjoyed the experience, so

he was happy to sign on when she came to him with another idea –

which became Pound of Flesh.

“I worked with Tammy on that movie

and it’s a very sweet, charming movie,” McDowell says. “We became

friends. I’m friends with the whole family. Tammy is a dear

friend. She’s an extraordinary woman. She’s seventy-something… I

don’t think she’ll mind me saying that… and has the energy of a

twenty-one year old. She’s a pretty amazing person, very talented,

a very good writer. She wanted to write a part for me and this is

the part she came up with. She wanted to explore the hypocrisy of

where we live and all the rest of it. I really enjoyed doing it.

It’s nice to play a guy who knows something about our great writers,

especially, of course, Shakespeare. That was fun, doing him,

Professor Noah Melville.”

In fact, McDowell is very natural

and charming as a professor. So had things happened differently in

his life, could McDowell see himself as a teacher?

“It’s a possibility. I think I

would have been a very good teacher. I think I would have

been.”

McDowell’s character, Prof.

Melville, says a couple of times in the movie: “Sex is the one

occupation in which women are paid more than men, which is why men

almost immediately made it illegal.” The professor does not really

see his little scheme as wrong or even so much as a money making

thing – it was just more of a way of making sure everyone gets what

they need, one way or another.

It leads one to

question whether the professor was right or was

he being a bit naïve?

“Obviously, he was a bit naïve

because he broke the law,” McDowell allows. “But, having said that,

I think there is tremendous hypocrisy about sex in America. We’re

so bound up. We’ll slaughter people in the streets, but we won’t

see a naked bum on television. It seems absolutely ridiculous to

me. Of course, he is rather naïve and he went about it, but his

thought is – and I don’t necessarily see it as horrendous – is that

these girls are going to come to college, they’re going to have

affairs, why not pay your college tuition in doing it? Also, with

guys who are going to treat you well and take you out to nice

dinners and restaurants and nightclubs, etc., etc. Now, you can

argue either side of it, but I think it’s fun to expose it and to

say, ‘There it is, now you talk about it.’”

Of course, many of the other older

characters in the film have strong feelings one way or the other

about what is going on,

however those feelings are not necessarily trustworthy.

Of course, many of the other older

characters in the film have strong feelings one way or the other

about what is going on,

however those feelings are not necessarily trustworthy.

“They’ve all got their agenda,

haven’t they?” McDowell asks. “Dee Wallace, who is such a

delightful actress – as is Tim, he’s a brilliant actor – she is of

course still angry at him for something in the past that is

obviously some kind of rejection from Noah Melville and she’s never

forgiven him. Timothy Bottoms is one of these people that has just

managed to slide above everything. He is as culpable, if not worse,

because he is indulging in these girls. Noah Melville is happily

married – a moral man and monogamous and very into his wife and

child. It’s a dichotomy there, and it’s interesting, the dynamic of

it.”

The professor’s scheme comes apart

when one of the girls is killed while on a date and the police start

looking at Professor Melville. Therefore, despite the fact that the

professor has nothing to do with the girl’s death he loses

everything – his job, his wife and daughter, his standing in the

community and must flee to keep his freedom. It seems a bit much

for the crime, somehow.

“I honestly think, yeah, that it

was a bit excessive,” McDowell says. “But, I think the

original guy got twenty years. Twenty years. Where,

literally, people that kill other people get out in fifteen.

That’s the hypocrisy we’re talking about. But, anyway, it’s

certainly a point of view.”

A point of view – that has

certainly been a constant in Malcolm McDowell’s career. He has a

tendency to take roles that make you think and react, whether it is

the schoolboy in If or the sociopath in A Clockwork Orange

or the utopian dreamer in Time After Time or the

tarnished professor in Pound of Flesh. McDowell likes making

people think and stirring debate with his roles.

Yet,

McDowell does not obsess about how his career is looked at. He just

does roles that he finds interesting or exciting; he can’t plan his

career around what people expect.

“Oh my God, I don’t really care

how they see it,” McDowell says. “Because what can I do about it?

I just work and do the best I can every time I go out. I hope… I

know I’ve given people enjoyment through the years. People have

told me. So, that’s enough for me. That’s great. If you can make

people happy for a brief moment and take them out of their misery,

then that’s enough.”

Also, if you think that you see

Malcolm McDowell in a film and have a handle on him, then fine for

you – but you’re probably wrong. So does McDowell have some

surprises up his sleeve?

“Oh, probably, but I wouldn’t tell

you,” McDowell laughs. “I mean, yes, there’s lots of things that I

do, because I’m not the person I am in the movies. Even when I’m

playing myself, you are never yourself. You only play yourself at

home.”

Email

us Let us know what you

think.