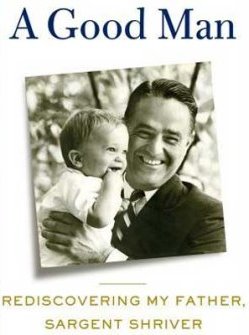

Mark Shriver writes a book about his dad, Sargent Shriver, first

director of The Peace Corps and avid letter writer.

Mark Shriver

recently published a memoir about

his father, called A Good Man, [Henry Holt & Company] shortly

after Sargent’s death from Alzheimer’s disease in 2011, at age 95.

Sargent Shriver was the first director of The Peace Corps

and The Jobs Corps, among other organizations that helped people

around the world escape poverty. He was also instrumental in

President Johnson’s War on Poverty during the Sixties, as well as a

driving force behind the Head Start program, which provides

comprehensive education and nutrition to lower-income children.

Mark took his dad’s inspirational lead. He heads up the US

division of Save the Children, which promotes children’s rights,

providing relief and support for children in developing countries.

It’s also easy to see from his looks and from his

commitment to public service that he is a Kennedy. His mother is

Eunice

Kennedy Shriver (President Kennedy’s sister), who died in 2009.

Together with her husband, they brought to life The Special

Olympics, which thrives to this day. Mark’s sister is Maria Shriver.

Here, we discuss Sargent Shriver’s imprint on the

conscience of a generation, as well as what Mark has learned from

this good man.

Your dad helped so many people and yet remained humble.

What was his driving engine?

Your dad helped so many people and yet remained humble.

What was his driving engine?

I think it was just the way he saw life. There wasn’t any

moaning about the past, worrying about his legacy. Somebody said to

me, “This book is a great legacy for your dad.” It kind of threw me

back, because I never thought about it. He never thought about his

legacy, like “I need to name a building after myself.” I think it’s

because he ultimately saw his work in the public sector and the

private sector as a way to do the best he could with the gifts that

God had given him. I know that sounds a bit old fashioned or maybe

goofy, but that’s the way he operated.

He was a genuinely happy man.

He had a wonderful relationship with my mom. These were

two really trailblazing people who had a marriage of 56 years. I

knew he went to mass on a daily basis. I knew he had a ton of

friends, and that people thought that he was special.

In this digital age, it actually seems quaint to learn

that your dad was a dedicated letter writer.

He wrote me

letters all the time, and I figured, “Oh, I guess everybody does

that with their kids.” I realize that that’s not true. I thought

everybody went to mass everyday and developed a relationship with

God and then I realized that’s not true. I think the book really

helped me pull all of those thoughts together.

Do you write letters and notes to your own kids now?

I write my kids now. I don’t write them nearly as much as

my dad wrote me. But they keep them too. It will mean something

different to them when they’re 21 and when they’re 31 and when

they’re 41. To have something in your father’s handwriting and to

realize that the guy was up at night thinking about you or thinking

about some idea, it’s a powerful thing for a kid, even if the kid is

48 like I am.

What makes a handwritten letter so special, especially now

that we have email and texts?

It has an impact

on me as a human being, to see his handwriting and to just remember

the pens he used to have in his jacket. They would explode and some

of his jackets had ink stains on them. You remember these little

things and you also remember that he took the time to write because

he cared and he loved. That’s a nice thing to have at any time of

your life.

My father wrote almost every night. I’d get one in the

mail at college every day and after college as well.

A text doesn’t have the same emotional connection. My kids

see that I take an 8 ½ x 11 piece of paper and write longhand to

them. It means that I thought about it and it means something more

than a quick text or a quick email.

When your dad started The Peace Corps, it was not an

immediate hit.

When your dad started The Peace Corps, it was not an

immediate hit.

In 1960, when President Kennedy got elected, President

Eisenhower thought the Peace Corps was a terrible idea. The Wall

Street Journal editorialized against it. Countries were wary of

allowing young Americans into their homes because they thought they

were spies. They were coming out of this whole era of colonialism

and here is the United States trying to send young people into this

kind of work. There was a lot of opposition from host countries and

from within this country. Yet dad created it out of nothing. And

it’s been around for 50 years. Right in the middle of that, when it

was four years old, President Johnson asked him to create the War on

Poverty, and again, it was created out of nothing. He came up with

the idea of programs like Head Start, which helps little kids enter

kindergarten ready to learn. Then he took the Special Olympics all

around the world with my mother. This is a guy whose whole life was

dedicated to helping the poor both here and abroad.

After all of

his achievement and outpouring of love, his being stricken with

Alzheimer’s disease must have been devastating to him and the

family.

When he was

struggling with Alzheimer’s I asked him, “How does it make you

feel?” Without missing a beat, he said, “I am doing the best I can

with what God has given me.” I think that’s really the way he lived

his life. He saw every moment and every person as a gift. He saw

each day as a gift, as corny as that sounds.

Alzheimer’s is a

brutal disease. As a country, we don’t spend enough time and

resources trying to find the cure. It’s brutal to see someone you

love fade day by day in front of your eyes. But there were also

moments of joy and insight that were very helpful to me.

What new impressions of your father have you developed as

a result of writing the memoir?

He was fully human. I needed to have

that message reinforced. It just encouraged me to be a better

husband and father and friend and spend more time with my faith. I

keep going back to that expression, “I’m doing the best I can with

what God’s given me.” I’m trying to figure it out. Am I doing the

best that I can with what I’ve got? And to be comfortable with that.

That’s hard to deal with in America too. In America, there is a lot

of pressure to be the alpha male, to be the big dog, or to be the

kind of guy who bosses your family around or boss your kids around,

and that’s not what he was about. That’s something that is important

to me that I’m trying to deal with on a regular basis.

Find out more:

The Peace Corps:

www.peacecorps.gov

The Special Olympics:

www.specialolympics.org

Save The Children:

www.savethechildren.org

Email

us Let us know what you

think.