Copyright ©2008 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

February 22, 2008.

Just when you think

everything that happened during the Holocaust has been chronicled, another

film appears based on a true story that offers another look at that horrible

experience in a way which hasn't quite been seen before. So it's no wonder

this Austrian film The Counterfeiters got nominated for the Foriegn

Language Oscar.

Based on the published memoir of Adolf Burger, it details the experience of

Salomon "Sally" Sorowitsch, a masterful member of the criminal underground,

who, upon being sent to a German concentration camp, agrees to help the

Nazis in their organized counterfeit operation — "Operation Bernhard" — set

up to finance the war effort against the Allies. Through a brilliant

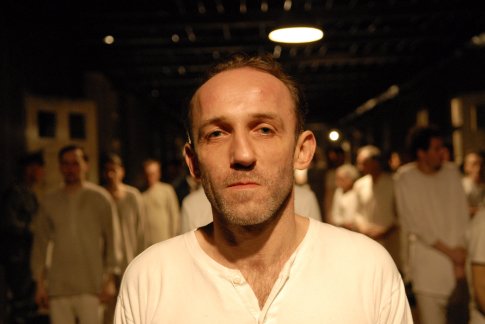

performance by veteran actor Karl Markovics,

Burger, one of Sorowitsch's fellow detainees (played in the film by August

Diehl) captures many of the traumatic decisions these prisoners grappled

with; help the Nazis and live or sabotage their efforts and die. In this

cinematic telling of this gripping drama, director Stefan Ruzowitzky (The

Inheritors) documents the inner war within the counterfeit workshop

against the backdrop of the Reich's final months while wrestling with

complicated issues of morality and survival.

Though both Ruzowitzky and Markovics aren't Jewish, they offered insights

into the impact of the emotional and psychological depravity wrought by the

Holocaust. A favorite to win the Academy Award, it's no wonder the film was

a hit at the Berlin, Telluride and Toronto International Film Festivals last

year.

You both made this film from the perspective of someone who isn't

Jewish... of not being someone who has the same imposing sense of that

experience and that definitely lent the film a different perspective.

You both made this film from the perspective of someone who isn't

Jewish... of not being someone who has the same imposing sense of that

experience and that definitely lent the film a different perspective.

Stefan Ruzowitzky: The thing that struck me was that these

[prisoners] are actually Germans. I tried to stay away from every cliché,

[even] positive clichés, that all Jews are intellectuals and cultivated and

wise people because this is something I learned from Alfred Burger's book as

well, that the people he'd been together with, they were Jewish blue-collar

workers, Jewish Prussian bankers and for me that was rather an interesting

thing. So here's a group of Germans and just because they have Jewish

ancestors they're put in a camp and the Nazis want to kill them; that's that

insane concept I've been thinking about a lot, and that struck me in a way.

It's also when Adolph Burger is asked whether he still hates the Germans or

whether he has problems with the Germans, he always says no because he'd

been in the camps together with so many Germans, German Jews [yes]—these

were people from Hamburg and Munich, whatever—but they were Germans as well,

so for him it wasn't Germans on one side in the uniforms and Jews on the

other. There were Germans on both sides.

And Karl, what about from your point of view?

Karl Markovics: For me it was much easier, because playing a Jew

never mattered to me because this character doesn't care about his

Jewishness at all. So it was much more [about] the point of why human beings

treat other human beings like that, and under what conditions. This was the

most interesting point for me and I hope that we will one day come to the

point that it doesn't matter at all anymore. At that time, [when] the story

[takes place], it mattered too much, today it still matters very much in

Austria and Germany, but there are not so many Jews left. On the other hand

there weren't so many at that time as well. This when I first heard about I

really thought I can't believe this, that only 0.8% of the German population

in 1933 were Jews. This small amount of population should be responsible for

all the evil happening to the German race? This number drove me crazier than

other facts of this part of our history.

How do you explain that it happened to so many people, yet their role in

society was so blown out of proportion?

Karl Markovics: It's only possible because of several centuries of an

ongoing tradition of having a minority within the [majority] population to

blame for anything you want. It's kind of a fashion, sometimes to protect

them and sometimes, the governors, the kings, the dukes and so on would

persecute them for any reason. Of course, [these reasons include everything

from] Christian ideas of they killed Jesus to the fact that they often were

really well skilled and well educated. The thing was that they often had a

lot of money because they were forced to only do jobs as bankers and the

economy stuff and then the people blamed them for that. So it's really

weird, but it seems to be human [is] to look for a minority you can blame

for everything. There was one famous line in one of my favorite American

novelist's books, Annie Proulx. In Accordion Crimes she writes that

even if there hadn't have been the African-American population in the States

there would have been an ongoing civil war between the Polish, Germans,

Scandinavian immigrants, but they all had the Blacks to look down on and to

kick and to feel better and this we did to our Jews.

It's an interesting permutation that your character is a criminal. His

alliance is less with the Jewish community and more with the criminal

underground. You successfully showed another side to this when these

different classes of people together were thrown together. That gave you an

opportunity to play the role with a unique outlook, and, for you, to direct

him with a unique point of view.

It's an interesting permutation that your character is a criminal. His

alliance is less with the Jewish community and more with the criminal

underground. You successfully showed another side to this when these

different classes of people together were thrown together. That gave you an

opportunity to play the role with a unique outlook, and, for you, to direct

him with a unique point of view.

Stefan Ruzowitzky: From the very beginning [that's] what intrigued me

the most, the pitch of having a counterfeiter in a concentration camp, which

is just a great pitch, a counterfeiter who's somebody who's betraying

somebody, who's manipulating reality and without knowing the details I

thought right away, well that's interesting. Will he be able to manipulate

reality in the camps? Will he be able to betray himself and things like

that? On top of that I felt it was very interesting, or it would be a

completely new perspective because all the autobiographies that we know

[about the camps] by Bruno Bettelheim, Primo Levy, all these were written by

people with an intellectual, bourgeoisie background, an academic background,

and here we have somebody who's sort of trained to survive and survive well

within a prison. Of course a concentration camp isn't a normal prison but

still he would know how to get along within the hierarchy of the inmates and

all these things. Doing research on the concentration camps I did find out,

[that] there were many criminals in the camps and they usually got along

much better and survived better because they were better at organizing

themselves for food and good jobs and all these things with a mix of

betraying, stealing, and just performing their skills. So I felt, well,

that's an interesting new perspective that I haven't heard about that

interests me.

To play a criminal who wasn't just an obvious hero was an extra wrinkle

for you...

Karl Markovics: Yes, definitely. That was the point for me, because

he's sort of a lonesome wolf. He thinks of himself as a lone wolf and that

he doesn't belong to all the others, all the rest of the world outside. [He

thinks] "I need them, I use them, but I stay on my own" and suddenly at once

in the concentration camp he's forced to belong to others because he's a

Jew. He's suddenly forced to be responsible for others, too, if he wants to

or not because his skills decide whether they will live for a certain time,

at least, or if they will be killed at once if he doesn't manage to make the

pounds and the dollars. So, he is forced to start socializing for the first

time in his life.

He's challenged with a moral dilemma that he wouldn't ordinarily be

challenged by.

He's challenged with a moral dilemma that he wouldn't ordinarily be

challenged by.

Karl Markovics: Right.

The film is morally complex. On the one hand you have a character that

advocates the idea of not helping the Nazi war effort but at the same time

there's the logic of wanting to stay alive and doing what you can to do to

survive; what were the challenges in presenting that point of view?

Stefan Ruzowitzky: The idea was to balance all that as well as

possible in terms of not saying there is a right way and there is a wrong

way. The idea was that you would watch Sally and say, "yeah, probably, I

would have done the same thing" and then you'd hear Burger talking about

principles and that the Nazis wouldn't have a chance if people would stick a

little bit more to the principles and you say, "yes I agree completely," but

you also understand the guy who said "I almost died a dozen times. I just

want to go on living." I just wanted to show that everybody's right in a way

and everybody's causing some special problems with their approach. Initially

I thought that audiences would fall much more for Burger because he's sort

of the typical hero with his ideals, so we have some scenes which show his

dark side as well, but then pretty early on I found out that the opposite

was the case. People love Sally because they can identify with him, because

that's what we all are doing, just sort of trying to get along somehow and

it's not always 100% correct. But we try to be good people which sometimes

works and sometimes doesn't. Whereas people like Burger, the movie character

not the real person, we admire them to a certain extent because they're

radical and idealistic, but at the same time they're boring and we all know

that they don't succeed with their big ideals and that often leads to even

bigger catastrophes.

Moral ambiguity is always more interesting than dogmatism.

Stefan Ruzowitzky: Yes and the interesting thing is I had one

screening in New York for the National Board of Review and there was a

couple of Cuban immigrants there. They said that when they saw him in the

first scene, recognized him right away because he was just the typical

Communist, saying "I have my ideals and I'm ready to die for my ideals and

I'm also ready for other people to die for my ideals." That's enough of a

dark side for Burger, so we didn't use these scenes I was referring to

because I felt he's negative enough in the eyes of many people.

Did you do certain things to create this character without being too

obvious and was the moral ambiguity a challenge for you?

Karl Markovics: It's hard [to say] because I don't really know how to

explain the process of acting, because I don't know myself. It happens. It

sounds stupid, but it is a little bit like that. One always tries to find

the symbols or analogies to explain something. So I could talk on for half

an hour, but wouldn't really say anything clever or smart. I don't know. It

was a challenge... a challenge for me in itself, to do this. The biggest

challenge was could I be able to put away my personal feelings, my feeling

of "am I allowed to play a Jew as a non-Jew?... To put away my historical

knowledge about this time, all the things we heard at school or I read in

books, because the guy I play doesn't give a shit about all this, he has no

political sense and is not aware of his Jewishness; he is what he is, I am

what I am and that was the biggest challenge... To be sure when we started

shooting, not to care about all this, just make it happen.

You bookended the film with an opening scene with a woman and the last

scene with a woman. What did you have in mind and was that for you to give

you him someone different to play against?

You bookended the film with an opening scene with a woman and the last

scene with a woman. What did you have in mind and was that for you to give

you him someone different to play against?

Stefan Ruzowitzky: From the very first idea and treatment I had this

frame and there were some clever people who said you shouldn't do that,

you're taking away a lot of suspense by showing that he stays alive. This

could be a big suspense thing and actually it was much later, actually some

interviews helped me to find out that what's happening here is the movie

actually starts with the ultimate happy ending: there's a guy after six

years in concentration camps, he's sitting on the beach of the Cote D'Azur

with a beautiful woman and a suitcase full of money and then he asks

himself, "why me? Did I come to close to evil? Did I compromise too

much?" This is actually what the movie is about and it's not that sort of

cheap thrill of "he's a Jew in the camp, is he going to survive or not?" but

it's rather about the how [of his survival] and I think that's far more

elegant than it would have been without the frame.

Is that why you decided to film this as more of an adventure story,

almost like a film noir?

Stefan Ruzowitzky: I wanted to make an accessible movie, a movie for

people of my generation who are not [feeling] guilty because we have been

born years after the war and I wanted to invite them to be interested in

that period of time because it's worthwhile to think about it. So I tried to

make an accessible movie which is emotional and suspenseful but not with the

kind of suspense of "are they going to descend into the gas chambers or

not;" that kind of cliffhanger would be disgusting. It's about other things,

[and that's] where the suspense lies.

Was it a pleasure to work with those two actresses?

Karl Markovics: It was a pleasure definitely, in different ways. Of

course it was a pleasure because it was a pleasure, but also [there was] the

opportunity that I really felt this clash of dimensions personally — we were

shooting all these [glamorous] scenes before we went onto the concentration

camp scenes. So we had been in Monte Carlo and it's at the Mediterranean sea

[we're there] with this beautiful suit and dresses in the casino; and we did

all this and then there was a short weekend and then [there we were] on

Babelsberg Studios lot with the prefabricated barracks and we started in the

[concentration] camp. It was sort of, you know, there is a cut in your life

and you can't imagine [it being] deeper. I felt a little bit like this

working the first morning before we started shooting with all my memories of

the Mediterranean and Dolores Chaplin and Marie Bäumer, the only two girls

in this movie, [fresh in my mind]. It was such a short time and then [we

started] going on to the real story.

Then there is the "real" unreality of this whole Oscar nomination thing.

Karl Markovics: Yes absolutely. It seems fake as well. You can't

believe there's really an Oscar. I'm sure it's chocolate [inaudible].

Did it catch you by surprise?

Did it catch you by surprise?

Stefan Ruzowitzky: Not really, because of the short list. You know

you have this short list with nine movies [on it from which they pick the

Oscar nominees for the international award].

Karl Markovics: I didn't know. You did? I was surprised.

Stefan Ruzowitzky: So you're kind of prepared, and I think you know

if you're among these last nine and then you don't make it among these last

five, that's really frustrating. Now of course I want to win but okay, if

you don't win you can't help it you know, but being among the last nine but

not among the last five must be really shitty.

Is there anyone you want to talk with or something special you want to do

at the Oscars?

Stefan Ruzowitzky: It's funny... It's similar to when a movie is

premiering and you have this red carpet situation. When you're there on the

red carpet in that situation they make you feel like you're the most

important person in the world and then one minute later you meet the same

journalists in the bathroom and nobody gives a shit about you. It's like a

play and you have your role, which is smiling on the red carpet as they

shout "Stefan, Stefan look here" and you look there and it works only in

that very moment and not later on and it's fun.

Karl Markovics: I want to meet Governor Schwarzenegger, my former

fellow Austrian citizen.

Email

us Let us

know what you

think.

Features

Return to the features page.