Though not quite the stars of Trumbo, actors Josh Lucas (Sweet

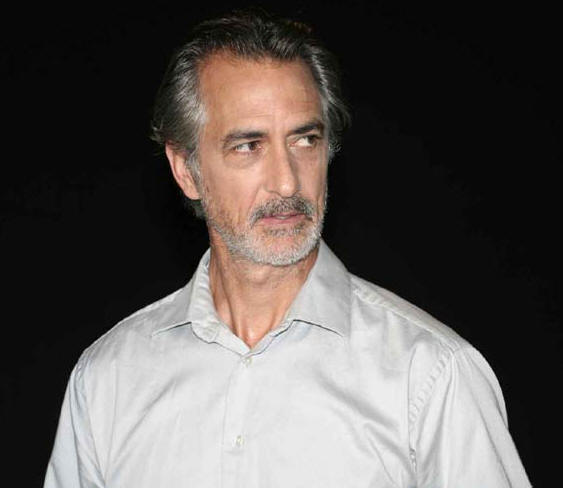

Home Alabama) and David Strathairn (Good Night and Good Luck),

join with Joan Allen, Brian Dennehy, Michael Douglas, Paul Giamatti,

Danny Glover, Nathan Lane and Liam Neeson to lend a theatrical voice

to this cinematic testament about the late screenwriter Dalton

Trumbo. Based on a theatrical version that had been staged in New

York and Los Angeles several years ago (created by Trumbo's son,

Christopher), this film uses the letters Trumbo wrote to friends and

foes alike, plus mixes in documentary footage, historical archives

and theatrical readings to make this award-worthy release.

In the first flush of anti-communist Congressional investigations

(they were witch-hunts really) led by Senator Joe McCarthy, Trumbo

was arguably the most famous of the "Unfriendly Ten" screenwriters

who were blacklisted in 1947. Until the early '60s, when Trumbo's

name finally reappeared on the films Spartacus and Exodus,

he wrote under a pseudonym for a very few producers who were willing

to help him.

Now through director Peter Askin's documentary, the dramatized

readings from Chris Trumbo's epistolary drama been couple with

newsreels, interviews, and the few film clips of Trumbo that exist

to fill the historical gaps missing from the play. Not only does

this documentary show how defiant Trumbo was, but how his insistent

visibility eventually helped break the Blacklist. More importantly,

it illustrates how easily the process to erode civil rights rolls

forward once things start down that slippery slope – as is happening

today.

Since Trumbo was such a prominent figure in Hollywood over a

half-century ago, it was important to discuss him and his legacy

with Hollywood stars Lucas and Strathairn – not just because they

portrayed him through these readings – but because both, in their

own unique way, have been so affected by his legacy. Both veteran

actors discussed their experience and his impact recently in New

York City.

Each of you brings something new to the Dalton Trumbo letters you

read. How did you get into Trumbo's head?

David Strathairn: Well, it's a steep slope to get into his

head actually, but I've done a bunch of readings of short stories

and play readings, and that's kind of the format. I tried to find

some music to it so it's listenable, and then what you are saying

starts to couple-up with that. When poets or writers read their

stuff, it's not performative and therefore, maybe not as engaging.

So the challenge was how you give his aesthetic, plus present it in

as clear a form.

Josh Lucas: I had a great experience last year, when I did

[the play] "Spalding Gray: Stories Left Untold," which was, in a

sense, the same format as this where you have actors performing as a

character in a way. They structured that play with five actors

playing five different essences of Spalding, and that created the

whole Spalding, because Spalding himself was so complex, and I think

there's something quite similar here in that you have a character

who has awesome literary intelligence and intellect, but also anger,

rage, and incredible humor.

Josh Lucas: I had a great experience last year, when I did

[the play] "Spalding Gray: Stories Left Untold," which was, in a

sense, the same format as this where you have actors performing as a

character in a way. They structured that play with five actors

playing five different essences of Spalding, and that created the

whole Spalding, because Spalding himself was so complex, and I think

there's something quite similar here in that you have a character

who has awesome literary intelligence and intellect, but also anger,

rage, and incredible humor.

The reason why the film works in this format is because watching

Nathan Lane do that piece on masturbation is amazing. And for me, it

was about saying how do you relate this particular story in your

life – who you are, and where you are – to what this man might have

been going through, and this was the process that was fun for me.

Particularly because my piece was somewhat romantic, and has quite a

bit of pathos underneath it because he's in prison as he's reading

it.

Did you choose the particular letters of Trumbo's that you read

or were they assigned to you?

David Strathairn: They were assigned. Peter [Askin, the

director] or whoever ], decided that these were the ones that were

assigned. I don't remember him saying why…

The actors reading the letters seem to embody, to take a word

from Josh, the "essence" of Trumbo, brilliantly conveying different

aspects of his persona. What sort of research did you do to get

yourselves into character?

Josh Lucas: I think one of the things the film had to deal

with in its construction was that there wasn't a lot of footage on

Trumbo, and much of it is used in the film, and I think that's why

actors were necessary to tell the story – to hear the letters, hear

the writing and the incredibly razor-sharp nuances of how the

letters are constructed like poetry.

So what we had to work with, for me at least, was not dissimilar to

what you see in the film. But mostly what Peter [the director]

wanted to do for us was to get our take on it, and not necessarily

by any means try to be like Trumbo or sound like Trumbo, or move

like Trumbo. Which is why its effective, moving from these

personalities like Donald Sutherland moving into another actor like

Michael Douglas, and the way that each person's essence is so

different.

David Strathairn: It was a great design. If you had done

Trumbo the way that they had done a traditional biopic – to have

one personality try to inhabit him – that's an impediment to the

material, because then everybody's going to be focused in on how

this particular person is inhabiting or presenting him.

In this way, you get a lot of different voices, and the variations –

or the collage of people – is entertaining, and refreshing

moment-to-moment, but it also in a way displays the universality of

what he says. It's a lot of people dancing on the same floor, and

you can see how substantial that floor is.

Many of the actors, including yourselves, convey much emotion

when reading the letters. Did [Peter] and screenwriter [Christopher

Trumbo] direct you towards this emotion?

David Strathairn: I don't know how it happened for you Josh,

but he just said "read it and hear it." It certainly wasn't "turn

right, here" it was more "I can see where that's going, do it

again," and it felt very creative and organic, with no sign posts

along the way. Because the material speaks for itself – you release

to it – and it is affecting. It's always tricky when you're

presenting something like this to not be overbearing, or not be

affected by your own particular stuff so you don't trample, because

maybe what he meant to be funny sometimes was also so full of

pathos. It's safe to be careful.

David Strathairn: I don't know how it happened for you Josh,

but he just said "read it and hear it." It certainly wasn't "turn

right, here" it was more "I can see where that's going, do it

again," and it felt very creative and organic, with no sign posts

along the way. Because the material speaks for itself – you release

to it – and it is affecting. It's always tricky when you're

presenting something like this to not be overbearing, or not be

affected by your own particular stuff so you don't trample, because

maybe what he meant to be funny sometimes was also so full of

pathos. It's safe to be careful.

Josh Lucas: Yeah, the guideposts were in the writing. No one

was telling Joan Allen, "This is when you should tear up." The

writing is so good. It's just infused with incredibly humor but

incredible pathos. I think there's a moment in the film where Trumbo

actually says, "All the greatest jokes have the greatest tragedy

underneath them," and so throughout reading it, there were still

moments where you couldn't help but be led a certain direction. And

the way Peter was directing it – this sort of black box element of a

group of actors in a theatre – was, "Let's see what happens."

How familiar were you with the works of Dalton Trumbo before

embarking on this project? Do you have a favorite?

David Strathairn: My introduction to him was Johnny Got

His Gun, and then I had been in the development of a project

years ago called The Hollywood Ten, so there was his presence

in that. And some of his films – The Brave One and

Papillon obviously – but not in as much depth as I've come to

find out.

Josh Lucas: Same for me. My parents were hardcore anti-war

activists, so Johnny Got His Gun was essential, and obviously

Spartacus. The letters were probably the most revealing, and

I think that's what the film in a sense is most concentrated on. And

I think those letters are extraordinary.

David, in your Oscar-nominated film Good Night and Good Luck,

you've already broached this subject of the blacklist, Joe

McCarthy's HUAC anti-communist investigations and the "Red Scare,"

albeit from an entirely different point of view.

David Strathairn: This [production] felt like you were in the

street reading Dalton's stuff. There was a little more grit and

affect. [CBS newscaster and analyst Edward R.] Murrow was obviously

insulated, but he got into the whole neurology of that time—pretty

incisively – but he, because of who he was, responded in a different

way.

So it was interesting to see that he had this forum where he could

at any given time speak to three million people, whereas Trumbo –

his megaphone was shredded, compared to the elegance of Murrow's.

But they were both coming at the same issues with I think as much

passion, although their aesthetic definitely was different. When you

read some of Murrow's stuff, he was as razor-sharp about the issues…

The two of them probably would've had a good talk.

Josh, you said your parents had been anti-war activists. What

insights did you gain from this, and is there a particular resonance

in light of today, with the Bush administration's (and the media's)

handling of the Iraq War?

Josh, you said your parents had been anti-war activists. What

insights did you gain from this, and is there a particular resonance

in light of today, with the Bush administration's (and the media's)

handling of the Iraq War?

Josh Lucas: The integrity of what [Trumbo] did was pretty

incredible. I grew up with that [as well], but in a time where it

wasn't as difficult to do, in the '60s and '70s, as it was for

Trumbo. So my parents weren't exactly rare in a way that I think

Trumbo was rare, and unfortunately I think we've gone backwards to a

time where it's become rare again, where its become incredibly

difficult for actors or politicians or personalities or citizens

period to stand up and say what they believe without having very

difficult repercussions placed on them.

I just did a film with Susan Sarandon [Peacock] who talked

about how there was a period of time where she felt like she was

bashing her head against a wall in a very painful way, and there

were repercussions. No one was blacklisted per se, but that was a

big shift in the country, to go from a time with my parents where it

was readily acceptable – I watched my father get arrested for

trespassing consistently, and it was "cool" – as opposed to after

2001, where anyone who was protesting in that way, literally,

[could] lose their jobs.

Actors who are doing it on a certain level like Sean Penn were

genuinely being demolished for it in a public sense and yet in

hindsight, it turned out well for them I think in a way, because

it's quite clear that, as in Trumbo's case, they were in the right.

But it takes insane courage, especially back then, to be one of the

only ones to say "I'm not going to allow this," and not only become

broke for it, but go to prison for it when you have young children.

That's integrity.

This film also celebrates a bygone era. It's an epistolary film

based on these beautiful, long-winded letters, whereas now we live

in the era of text-messaging and abridged conversations.

David Strathairn: That's a great observation because in a way

it was a bygone era, but letter writing was amazing. People think of

it as some archaic art form, but that was really how people

communicated. I just did a play about Brutus and Cicero,

"Conversations in Tusculum," and they were like the original pen

pals. They wrote volumes to each other.

Josh Lucas: I don't know about you, but I'm at a time in my

life where when I text, I'm forcing myself to use full words

[laughs]. And I'm forcing myself simply because it's for me to do,

not for the other person because everybody now is getting to know

these abbreviated words, and the idea of sitting down and writing an

elaborately, well-constructed, beautifully-worded letter to the

phone company, it's extraordinary.

David Strathairn: Yeah. So if the film just does just that on

a historical level, great. To make people aware, of all the

political resonances and personalities that are in it, [even

better]. But that's something that people sort of look back and say,

"Oh yeah, people used to write letters and used to [mimics typing]."

Did this project make you want to do more theater?

David Strathairn: Yeah, I just did one in March. But hey, I'm

always looking to do theater.

Josh Lucas: I haven't done one in about a year myself, but

it's what you search for constantly. It's a question of how you make

a living doing it, and when do you find a piece that you want to put

out into the jaws of the New York critics, because it's a really

difficult environment. It's a very mean environment in a way, so it

has to become something you have to do if you really love the piece.