It’s hard to believe that in a career that has lasted

over 40 years (actually longer, his first appearance on film was

in 1951 as an infant), Jeff Bridges has never

won an Oscar. He has worked regularly and made vibrant contributions in

such legendary films as The Last Picture Show, Starman, The Big

Lebowski, The Fabulous Baker Boys and Fearless, yet he

has only been nominated four times and has never brought home the little

statuette.

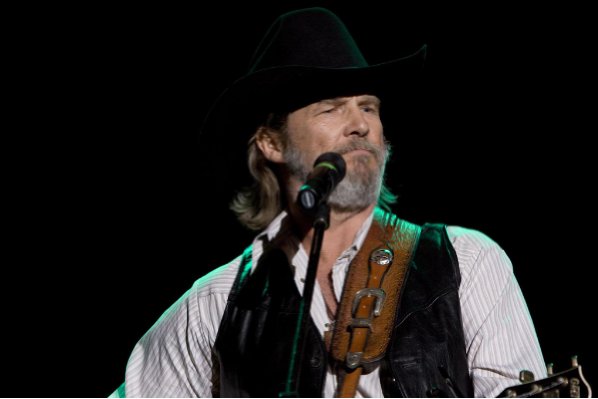

This may all be changing with his latest role. In Crazy Heart,

Bridges disappears into the role of an aging country singer named Bad

Blake who is fighting with his demons when he is offered two chances of

salvation. One comes in the form of a potential family with a younger

woman (Maggie Gyllenhaal) and her son. The other is through his career,

with an old protégé (Colin Farrell) becoming a country superstar and

wanting to bring his old mentor along for the ride if the older guy

could just swallow his pride.

Crazy Heart is the

writing/directing debut of character actor Scott Cooper and features a

wonderfully realistic alt-country soundtrack written mostly by roots

musician/producer T Bone Burnett and old Nashville hand Stephen Bruton,

who died before the film saw release.

A little under a week before Crazy Heart was set to be put on

limited release so it would be eligible for Oscar consideration (and a

matter of days before Bridges was nominated for a Golden Globe for the

part), Bridges sat down for a roundtable with us and

some other websites to discuss

his career, the movie, the role and the Oscar buzz.

You’ve been involved

with music for years – in fact I have the CD

that you did about ten years ago [called

Be Here Soon]…

You’ve been involved

with music for years – in fact I have the CD

that you did about ten years ago [called

Be Here Soon]…

Oh, yeah? Oh, good. Good, good, good. Ten years ago? Is that what

you said? Jeez… Has it been that long? Phew, it probably has.

Do you think that had

things gone a different way for you when you were starting in show biz

you may have ended up having a life like Bad’s?

I don’t know about Bad’s life. I hope not. (chuckles) You know

I’d certainly get into music. Unlike a lot of people, my father, Lloyd

Bridges – who had a hit TV series in the 60s and was a very successful

actor – he enjoyed show biz so much that he really wanted to turn his

kids onto it. So, he encouraged all of us to go into show biz.

And

as you know, we don’t like to do what our parents tell us to. So I

wanted to do the music thing, or to paint, or some other stuff. But I’m

glad I took the old man’s advice, because I sure love it, too. And all

those other things I might have gone into, I can bring to the work, like

in this one.

In Bad Blake, we see so many country singers we know – Waylon Jennings

is the first one that comes to mind. In your research creating this

fellow, who inspired you?

I was really fortunate in this one to have two very close friends who

were my main role models: T-Bone Burnett and Stephen Bruton. Those

guys, we go back to Heaven’s Gate 30 years ago, with another role

model – I’m not as close with [Kris] Kristofferson, but he’s certainly a

good buddy, and he brought all his musician friends to that party. So

it was six months of jamming, every night after work. That’s kind of

the birth of this movie. It came out of that in a funny sort of way.

And Kris is certainly a role model. One of the first bits of direction

Scott [Cooper] gave me was that if Bad was a real character, he would be

the fifth Highwayman. Do you know who The Highwaymen are? Kris, Willie

[Nelson], Waylon and Johnny Cash. So those guys were all role models,

along with Hank Williams. Then, another thing that T-Bone told me – and

I thought it was really a great idea – he gave me a timeline of the

music Bad might have listened to when he was growing up. T-Bone and

Stephen grew up together – they were childhood friends, basically – and

Stephen’s dad owned a music store and exposed them to all kinds of

blues. They would listen to Ornette Coleman. All kinds of music. T

Bone said, ‘Country music comes from all different kinds of places now,’

so Bad could be listening to T-Bone Walker or Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen

– different guys that aren’t thought of as classical country guys. They

were role models as well.

How easy was it to get out of the mindset of the character?

How easy was it to get out of the mindset of the character?

Oh, a certain part I don’t want to get out of. Keep that guy with me,

you know? Just the music stuff and hopefully, I’ll keep on with that.

Maybe another album will come out now that he has done those kinds of

things? So, that aspect of the character is still cooking. The other

side, you know the boozing side and the unhealthy side, like gaining

that much weight… part of the preparation for a character is you think

of what you ingest. Whether it’s a cup of coffee, or how much you eat

at lunch that day because you have a scene. How you feel sleepy after

you eat… all those kinds of things. So with this lot, my regimen was

“remove the governor.” Take that guy and put him over there. You want

that extra pint of Häagen-Dazs? Sure. You want that extra drink?

Sure, go ahead, man! You don’t want to drink when you’re working,

because you’ve got to sustain that kind of thing. But you be a little

humble, that might work for you. Giving that up was a little bit tough,

but there is a downside. It’s like the blessing of the hangover. The

hangovers let you know: don’t do this too often. We learn that lesson

over and over. (laughs) Well, hopefully, not too many times, if

we’re lucky. So that side was a little tough, because you kind of get

in a groove, and the older you get, the harder it is to shift: lose the

weight and all that stuff. But there’s nothing like health – that’s the

best high.

What about the cigarettes?

There are so many!

Oh, yeah. That’s always a challenge. At least they were filtered

cigarettes. I remember doing Tucker. The guy died from lung

cancer. He smoked three packs of Luckys a day! Or Chesterfields. Oh,

my God. I’d be puking during a scene, you know? Because when you’re in

the character, you just play it. You’re doing it how you do it, and

then after two or three takes you go… (moans)

They can’t give you fake ones?

That doesn’t even matter. That doesn’t help that much. That was never

my jones, the cigarette thing. I always draw the line at never buying

cigarettes. Whenever I’d get that urge to smoke, I’ll have to bum a

cigarette off someone.

Do you think Maggie’s character was right to break off the relationship?

Yeah. Man, yeah.

I kept hoping they’d get back together.

I know. Well that happens in the sequel, you know, Crazy Love.

(laughs) Her guy turns out to be a terrible guy and I come to

the rescue. I write a song about it. I write a song about the kid.

No, I don’t know. That’s my optimistic mind, though.

I heard there might be a sequel to

The Fabulous Baker Boys.

Did you? Ooh, I hope so. There should be!

Do you see any commonalities between this character and the one you

played in that?

Do you see any commonalities between this character and the one you

played in that?

Yeah, now that you mention it, I hadn’t thought about that before. But

I bet there is. I think they both get caught up in this myth that a lot

of these artists do – about suffering being the source of their talent,

so they keep that going in the subconscious. I love that line in the

song from this one, “I used to be somebody, but now I’m somebody else.”

Bad probably wrote that song thinking, “I used to be famous, and now

I’m not famous.” But if you flip that around, I don’t have to be

punishing myself as much as I do. I don’t have to be this guy, this

myth. I can get off of that wheel. I don’t have to keep playing that

same tune. That’s kind of a positive thing.

In the promotion of the movie, they seem to be downplaying Colin

Farrell’s role – I didn’t even know he was in it until he appeared on

screen.

I think that might have been his decision. I think, don’t quote me on

that. I’m not sure. That’s a good question for the producers.

[Ed. note: Writer/director Scott Cooper confirmed that Farrell asked

for his part in the film to be downplayed in promotion because he didn't

want to steal any of the spotlight from Bridges and Gyllenhaal's lead

performances.]

How was it playing the mentor-protégée relationship with him?

Oh, God. He was so great! He came in for maybe four days or something,

and gave that great performance. That’s one of the challenges of doing

movies, is that you have such a short period of time. We shot this in

24 days, so you’ve got a very short period of time to get up to speed,

and to get as deep as you have to get to make it a good movie. And

Colin certainly did that. He was wonderful to work with. As well as

great to sing [with] – harmonizing with another actor, people you are

working with. It’s kind of a great metaphor for what we’re trying to

do.

You are so vulnerable in this role, doing scenes in your tighty-whiteys

and passing out on the floor. What did you think when you read the

script? Did it make you nervous at all, or were you gung-ho?

Not really. That’s part of the role. I was not too concerned. I had a

thong on under my tighty-whiteys. (laughs)

You’ve worked with some amazing women

– Kim Basinger, Michelle Pfeiffer,

now Maggie Gyllenhaal. What makes a most unforgettable screen romance?

You’ve worked with some amazing women

– Kim Basinger, Michelle Pfeiffer,

now Maggie Gyllenhaal. What makes a most unforgettable screen romance?

Well, a lot of it depends on the play. The story, what the lines are.

Not even the lines, just the relationships. I think one of my favorite

moments was with Kim in The Door in the Floor, just saying

goodbye. I don’t think we even said any words, we just looked at each

other. That’s just kind of the story you’re telling. There are so many

different approaches to acting. Maggie is a person who approaches it

how I do, which is getting to know the people you are playing with as

well as you can, so you can bring some of that genuine friendship and

caring up to the screen. Kim works in a different way, where she is on

1,000% between “Action!” and “Cut!” but between those things there’s not

so much engagement. But that doesn’t matter, because there are many

different ways to approach the work, and both can be effective.

There can be an uneasy line to tread when you’re playing a character who

could be potentially unlikable. Here the audience is with you. Even

when they watch you getting out of the truck with his bottle of

questionable substance.

(smiles)

Gatorade. It was Gatorade. (laughs)

The audience is with you even before Bad has established himself as a

good guy. How much of that is the character, and how much of it just

that we like Jeff Bridges?

It’s probably kind of a combination of all those things. In a general

sense, making a movie is sort of like a magic trick. There are all

kinds of sleight of hand things going on, and there’s also real alchemy

going on. You’re kind of summoning up the muse or whatever. And what

you were saying about the story and what it says in the script is on the

writer. Then, my approach, I try to make it real and interesting. I

hear you saying that what holds your attention doesn’t necessarily have

to be that the character is a good guy, but there is something that

makes you wonder what’s going to happen next, and care about that. It’s

like in life. In life, you don’t have to like some guy who’s walking

down the street, but for some reason you find him fascinating. Whether

he’s just talking to himself – and you’re like what’s he saying? What

is that? You don’t know quite what it is, but you find it kind of

interesting. But, you don’t necessarily like him. I think the same

things are working in movies, too. It’s finding that thing that is

interesting but doesn’t pop, doesn’t rip the fabric. There are so many

different things in movies that are like that – from wardrobe to

makeup. You don’t want the makeup to look… God, that’s wonderful

makeup. You want it to be invisible. You don’t want to see that. Or

the clothes. You want it, like, you’re dressed really interestingly.

[gestures to one of the writers on his right] It would be cool

if a costumer said, “Let’s dress a guy like this.” Well what’s he

like? It doesn’t matter, but he’s so fascinating. It’s real and it

goes with the thing. So, to come up with those kinds of things – other

aspects – that’s kind of what we go for.

Do you need to like a character to play him?

Do you need to like a character to play him?

Umm, like him…? Feel compassion, I guess. Is that kind of like? Is

compassion liking? I guess, kind of, if you have compassion for him.

Some people are comparing

Crazy Heart to The Wrestler [with Mickey Rourke], saying you

should be up for an Oscar. How do you feel about that?

I like to be dug. (smiles) I like somebody to appreciate what I

do, especially the guys who do what I do. That feels great. I’m not

counting any chickens, but it feels good, I’ve got to say. Plus it also

feels good to bring attention to a movie that I’m so happy with, because

that’s what these awards and the festivals can do for a little movie

like this that can’t afford big print ads and getting people into

theaters in other ways. This is a way to do that, so I’m happy about

all that.

It seems like Bad isn’t lonely, he can go home with women from shows

pretty much every night. She is younger and has a four-year-old, which

sort of like an instant family. What do you think draws Bad to Maggie’s

character, Jean?

I think those things definitely drew him to Jean. Also, I think, seeing

that he’s been married four times before, he’s looking – the wonderful

thing about marriage, I’ve been married going on 33 years, it’s like a

playing field to get as deep as you can with your soulmate. It’s a

structure you can move in, and do that, and become as intimate as you

possibly can. I think he is longing for intimacy, for somebody to

really know him for who he is, even though he despises parts of himself.

That’s what’s kind of tragic and uplifting about this, that when he

finally shows who he is, an irresponsible drunk, it’s an impossible for

the woman he would love to know him. It’s an impossibility, but it does

wake him up with a big splash of cold water.

How did you come to this project? Was it your relationship with T Bone?

No, it came to me, and I originally turned it down. Because while I’m

always looking for a movie that has to do with music, [The Fabulous]

Baker Boys set the standard really high. I had such a great time

making that movie and we had Dave Grusin and all those great pop and

jazz standards. But in this one, they didn’t have any music and there

was nobody at the helm of the music. So, I was happy to say, “No

thanks.” But then T Bone [Burnett] got involved. About a year later, I

ran into him, and he said, “What do you think about this script?” I

said, why? Are you interested? He said, “Yeah, if you’ll do it, I’ll

do it.” I just said, oh, gosh, well, let’s go! (chuckles)

Also, Stephen Bruton unfortunately died during the filming. How much

did he bring to the music and the character?

Also, Stephen Bruton unfortunately died during the filming. How much

did he bring to the music and the character?

He was the whole thing. He died, not during the shooting of it, he even

got to do some of the polish up and put the music together with T Bone.

But, he was the whole deal. His life so closely paralleled Bad. He

would be the guy driving from gig to gig, hauling all his own gear. And

he certainly had problems with booze and other substances. He knew

about all of that stuff, and was encouraged by me and Scott and T Bone

to… any time he had any little impulse about what that might be like,

what it was like for him in that situation, we said, “Bring it on,

Stephen.” And he would. That’s all up there on the screen.

That store you were talking about, where Stephen and T Bone grew up, was

it in Houston?

I think Fort Worth, maybe.

What do you want audiences to take away from the film?

The words “waking up” kind of come to mind. We can wake up from our bad

dreams that we put ourselves in. That comes to mind. There probably

are some other things. I guess so much of the movie-going experience

depends on what you bring to it. What you’re thinking about and feeling

when you sit down in a movie. So, if you’re a young mother who has a

child and you’re thinking about settling down with an alcoholic

(laughs), it might be she maybe won’t do that. I admire the woman

who is thinking about her child instead of herself.

The movie is coming out in the middle of a bunch of blockbuster films.

Do you think people will react to a smaller story?

Yes. One of the themes in the movie is a reaction to rootsy country

music as compared to the normal more orchestrated [country].

This movie is maybe a response to the big tent-pole movies. You’ve got

that kind of dynamic going. In a way, those

poles kind of support each other. You have a blockbuster movie, [then]

you get some artist saying, “Let’s make a fucking kind of down-home,

gritsy thing.” You have that and then it’s like, “put some strings on

that, or some French horns.” Those are kind of working together, you

know?

You have done a lot of work with charity. What has that taught you?

You have done a lot of work with charity. What has that taught you?

Our kids… children are a wonderful compass for us. For our direction,

we are always going ahead. And our country is way off course. I just

got the statistics that the Department of Agriculture have been

following food insecurity since 1995 and they just gave their report.

“Food insecurity” means you live in a household where one of the kids

might have to skip a meal at night or they all take turns. Tonight’s

Thursday, that kind of thing where they don’t have enough nutrition to

study in school – to have the calories to be able to memorize. Not only

mentally and physically, but emotionally, spiritually, socially… in all

kinds of ways. So the statistic is 16.7 million of our kids – that’s

one in four – live in conditions like this. One in four! It’s gone

up 34% between the years of 2007 and 2009. Soup kitchens are up like

30%. If some other country was doing this to kids, we would be crazy at

war. But here, it’s ourselves. It’s like that Pogo thing, “We’ve met

the enemy and they are us.”

Are you still involved with that charitable organization…?

Yes, the End Hunger Network, something I helped found about 25 years

ago. We shifted our focus to hunger here in America. We were

concentrating on world hunger when we first started, but can’t be

telling people what to do if we can’t do it ourselves, so we shifted our

attention to here at home. The good news is that Obama has declared

that we can end childhood hunger by 2015. That’s kind of like Kennedy

saying, “We’re going to put a man on the moon in ten years.” So all of

the sudden, all the arguments and people saying, “Oh, there’s not really

hunger,” all those things now become an effective way of trying to find

the answers now. He said there will be resources. We know how to do

it, because we had that program that reflects it. They were effective,

but now they are not being funded. They are not getting support. So,

we’ve got to support those and then get some leadership. Get people to

make their contributions whenever they can. That’s the good news we’re

trying to get behind.

What’s next for you?

I’m going back to work with the Coen Brothers in [a

remake of] True Grit.

Is there anything from this character that will help you with that?

Both are alcoholic. (laughs) Oh, God, taking the governor off

again, damn it. I’ve got to play me a healthy, skinny guy next.

When will you be filming with the Coens?

In March we start.

And are you in

Tron Legacy?

I’m in Tron. We’ve shot that. That’s all done.

Is it the same character as you played in the 1982 original

Tron?

Yeah. It’s kind of the same thing. It appealed to the kid in me.

There was an aspect of advanced pretend. It’s like, come on, you want

be this kid who gets sucked inside a computer? Oh, man!

And now the technology is so much better.

Exactly! The new one makes the old one look like an old black and white

TV show. The stuff they’ve got going is phenomenal. I can’t wait to

see it.

Features Return to the features page