Copyright ©2007 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

May 19, 2007.

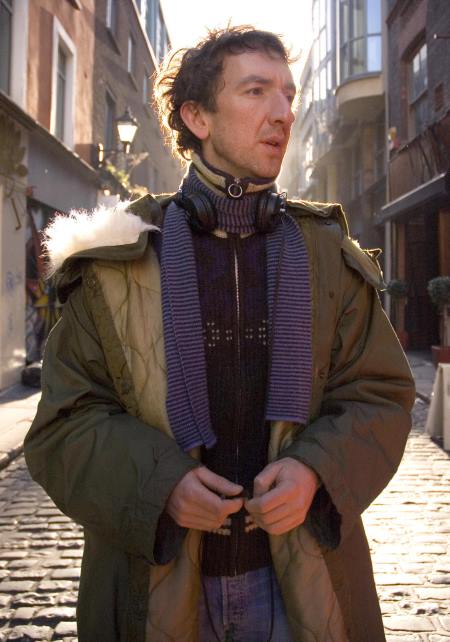

Fashioning a hybrid

from two cinematic genres can either pay off or be a profound failure. In

the case of John Carney's debut feature, Once, he succeeds handily.

Maybe that's because he enlisted his longtime pal and former band member,

Glen Hansard, lead singer of Ireland's hot rock band, The Frames, to play

the lead character in his entrancing folk-rock fable.

Hansard formed The

Frames in 1990, as part of Dublin's expanding rock scene. Merging folk with

rock, the band maintains a balance between energetic and pacific through

Hansard's crisp songwriting, authentic vocal delivery and the simple yet

somehow original song structures.

Hansard quit school at

thirteen to busk on local Dublin streets, but

first garnered solo attention as guitar player 'Outspan Foster' in Alan

Parker's film The Commitments. He then presented the television show

Other Voices: Songs from a Room, which showcased Irish music talent.

Last year, he released his first solo album, The Swell Season, in

collaboration with Czech singer and multi-instrumentalist Markéta Irglová,

along with two other friends. Then he made Once with Carney directing

and Markéta as the other lead; it won the World Cinema Audience Award at the

2007 Sundance Film Festival.

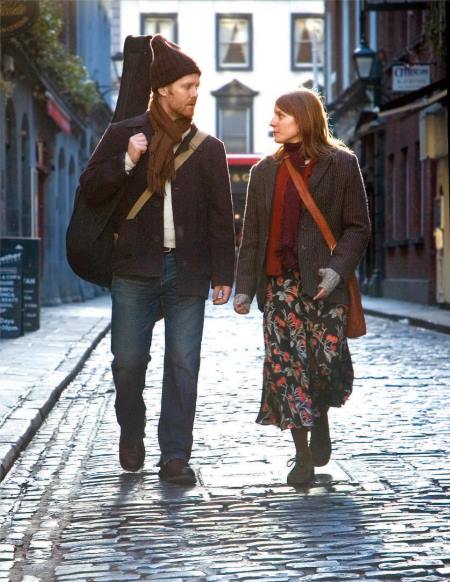

Once

is a very matter-of-fact tale of a street musician who meets a girl, a Czech

immigrant played by Irglová, near Dublin's city center where she inspires

him both with love and with music. But as the film merges two love stories

-- one about his love of music and the other his love for a woman. It

becomes neither a concert film nor strictly a love story. There are

performances and touching sequences but they never become too melodramatic

or predictable. And since Glen Hansard's music is so great, this makes for a

fine debut.

So, John, your attempts at being a folk-rock singer failed. Is this how your

film career emerged?

So, John, your attempts at being a folk-rock singer failed. Is this how your

film career emerged?

John Carney:

Well, I come from a reasonably musical family. My older brother was a music

lover and made it his thing to go out and discover weird bands in the '70s

and '80s that no one else knew about; he brought their [recordings] home and

exposed his younger brothers, myself and Kieran, to this obscure music. So

we had a piano and he brought a guitar and it was put under the bed. I

wasn't allowed to play it but I went and played it when I wasn't supposed

to. Like at 2 o'clock in the morning, I played his guitar.

So I always played

music. Then I met Glen when I left school and I joined his band. We played

together in The Frames for a few years. Basically, I got bitten by the whole

film thing and I went off to try and seek my fortune as a film director in

Ireland which is kind of an odd thing to do at the time because it was

pre-Irish Film Board. There was no money and it wasn't state subsidized and

it had just Jim Sheridan and Neil Jordan. They were the two lads and they

had their houses up in Dalkey overlooking the hills. So it was a funny

time.

I made a couple of

films. Myself and Glen met up a number of times along the way. Our paths

crossed and we said we should do something together. You know, "I'd love to

use a couple of your songs in my film" or I would take him and say, "I'll

shoot a video for you or your band. Is there someway we can kind of share

what we've done and let our two artistic endeavors kind of cross over?"

But it never happened

and there was never anything to do together. So I came up with this idea

simply of a busker and an immigrant, in what is kind of a musical, because I

wanted to try and do something that would get this musical thing out of my

system. I love music and I'd stop writing scripts and go off and write at

the piano and stuff for like three hours. I'd waste three hours or four

hours a day just playing Billy Joel songs at the piano and I would be like

what the hell, I just wasted hours doing that. I got to put this into

something. So I wrote a musical film.

How did you get

started, Glen?

Glen Hansard:

Well I have this uncle in my family who was a very charismatic character. My

mother comes from a family of thirteen kids and he was one of the younger of

the thirteen. He was this amazing guy and it was a very working class family

and he had this character. He did a bit of acting and was a musician and all

the girls loved him. He was very good looking. He had gray hair, all the

family loved him, the women loved him – you know. He was kind of a hero to

all of us as young boys.

At one point during

our lives, he disappeared and my mother was like "Yeah he's gone away." It

turned out he had taken a car and driven it across Europe filled with

something illegal, and had gone to prison in Turkey for many years.

His nice guitar got

left in our house, and his car, which is a four door amazing Ford Explorer,

had been left in our garden and I was kind of wondering where he was. My

mother kept stopping me from taking the guitar because I would just take it

out and have it on the floor and be like [strum noise] and I just really

enjoyed the sound of it, [but] she kept on putting it back.

His nice guitar got

left in our house, and his car, which is a four door amazing Ford Explorer,

had been left in our garden and I was kind of wondering where he was. My

mother kept stopping me from taking the guitar because I would just take it

out and have it on the floor and be like [strum noise] and I just really

enjoyed the sound of it, [but] she kept on putting it back.

It was a really nice

guitar. Like a Gibson Hummingbird. A beautiful instrument. She thought I

would wreck it but after a year of slapping me on the wrist and putting it

back she realized – my mother was a real Leonard Cohen fan – maybe it would

be a good idea if she'd teach me "Bird on a Wire." When he got out of prison

and came to the airport when all the family was there to greet him, there

would be his nephew with his guitar playing him a song – as if to say, you

have been a good influence on the family. So that was kind of how it

happened. I learned to play "Bird on a Wire" on the guitar. I taught

myself.

How old were you at

the time?

Glen Hansard:

I suppose I was about nine or ten. I went to the airport and of course as he

came through, it was a big deal. He came through the arrival stall and the

first thing he said is "my fucking guitar!" [laughs] It was wrecked

because obviously I'd been dragging it around the flat because I had no idea

that you keep this thing precious.

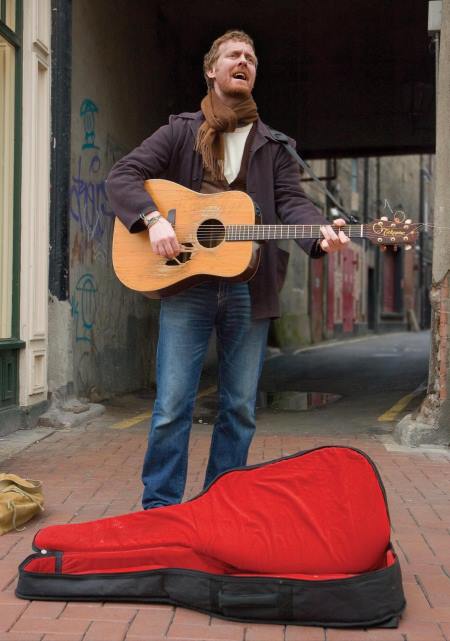

But it was completely

anti-climatic because he took me into his band and I played music with him.

Then at the same time my school teacher advised me to leave school at the

age of thirteen, which was a couple of years later, and take on the goal

basically of being a street musician. He said the best place to start your

career would be the streets because it's the bottom rung. It would teach you

everything you need to know. I learned to play a couple of chords from my

uncle, and being a street musician is where I got my education.

John, what gave you

confidence that Glen could actually carry the film? He can act but is not

necessarily an actor.

John Carney:

Well, being a director, I originally thought I would get Cillian Murphy to

do the role because I know him and he can sing. He's quite a good singer. I

thought you would do the usual thing – get a good actor who could half-sing

and maybe train his voice, which is one way of going. [But] it certainly

became clear to everyone involved in the film that we should do it the other

way around. We should get someone who can really sing and half-act and I'll

trust that I could do something magical with that, and I really didn't have

to do much.

I knew Glen for long

time and, really, being a director you know there are a million different

styles of acting. When you look at a person, you decide to employ a certain

approach and style. Directing a non-actor or someone who acted a little is

really knowing them and knowing their personality and putting them into a

situation where they're comfortable to read your lines and bring this

character to life. An actor can take different directions but I kind of just

knew him. I figured he would be great by the end of the day.

Glen, what gave you

that confidence?

Glen, what gave you

that confidence?

John Carney:

He didn't have much [laughs]. Glen said, "If I'm rubbish just sack me

on the first day." [Talking to Glen] You were worried.

Glen Hansard:

I was terrified for a few reasons. I didn't want to suck for his sake and I

didn't want to suck for mine. I'm a really comfortable person behind a

guitar but in front of the camera it's a whole different ball game. I didn't

know if I could do it. So I really needed him to tell me the truth.

Am I rubbish? Are we

pulling this off? Is it going to work? Because if it isn't, then let's just

pack it in. Because I thought really when they chose me, John was just

jumping on the nearest person.

I was thinking that if

John had really wanted me to play this role he would have asked me at the

beginning. Maybe I'm the rebound [choice]. But at the same time it made a

lot of sense. This would be something where I was dealing with my mates. It

was a big deal with loads of people telling me this and that. It was a very

obscure scenario, which I never felt attached to at all. Whereas John was

like “Look, let's just do it and if it's shit we'll just shelve it; if it's

brilliant we'll sell a few DVDs to make the money back." That was the logic

so we basically had to look at it with an open mind.

You describe this

as a visual album. How hard was it to translate that? You might have it in

your head but music is such an interpretive thing. How hard is it to get

that on the screen?

John Carney:

Well, I put Singing in the Rain and A Star is Born in the top

10 films of all time because they are [great] films. If it's a Sunday

morning and it's raining and I stay in I put on the scene from Singing in

the Rain. Or the scene between Marlon Brando and Jean Simmons in Guys

and Dolls just to hear a song because it's like an album. So you expect

to sit back and watch this great scene and the dialogue is brilliant. But

only about 10% of all the great musicals I would rate highly and the rest I

hate.

I'm not a great fan of

musicals. There are only certain ones I like. So I wanted to make a modern

day musical. I wanted to try and figure out how do you take a younger

audience that don't like those films, which can't accept people breaking

into songs, sitting back and watching a film and leave the cinema after

watching eight or nine songs in their entirety. So it quickly became clear

to me these would be the tools. I would film it on tape. I would film it

with un-actors. Make a really small little story. The story was really

secondary to the visual album-ness of the project.

So it was always

something that I wanted to do and address where you leave the film unaware

that you just watched all these songs but you're like, "Well it didn't seem

like we were watching a film with all these songs."

Can you guys talk

about the relationship between the songs and how they evolved?

John Carney:

Basically, it was collaborative. I liked the idea of being able to go to the

songwriter for the musical. With the Gershwins or Harold Arlen, the music

was there.

Most of the time the

songs were given to you and you wrote a story around song. But I like being

able to go to Glen and say, what do you think of this for a scene or idea

for a character. He would take it and come back with a lyric or a title or a

song and give me a song that he had written ages ago. So there's kind of a

scene and a song here where we bounced off ideas. The skeleton of the story

was in place: guy meets girl. She's this. He's this. He becomes

broken-hearted. They come together. Didn't we Glen?

Glen Hansard:

Yeah it was great. John came to me and said I need a song called "Once." He

said "It's the only part of the film where we are going to suspend reality;

we're going hire a crane which will cost us five grand so we need to get it

fucking right." We knew he needed a song for when Markéta [Irglová] walks

down the street and we will have her do a musical moment, so we need that

song and it needs to be very strong. It needed to have a beat and we need it

to be a song-song. Not just acoustic guitar and vocal.

Glen Hansard:

Yeah it was great. John came to me and said I need a song called "Once." He

said "It's the only part of the film where we are going to suspend reality;

we're going hire a crane which will cost us five grand so we need to get it

fucking right." We knew he needed a song for when Markéta [Irglová] walks

down the street and we will have her do a musical moment, so we need that

song and it needs to be very strong. It needed to have a beat and we need it

to be a song-song. Not just acoustic guitar and vocal.

We were acting during

the day and going back to the flat and basically picking up the guitar and

going "we need this and this and this" and we still hadn't finished this

song. It was a very creative moment. We'd finish in the evening and

basically go back, pick up the instrument and start to work on the next

song. So it was very intensive.

How different is this

music from the music you do as a band?

Glen Hansard:

That's the beauty of it. It's actually the same. Some of the songs that are

in this film are actually on The Frames record. It was one of those things

where I just wrote a bunch of songs because that's just what I do and then

for the film John wanted specific other songs which me and Markéta went off

and tackled. For the most part that's just what I do. John made a point last

night that if anyone doesn't like the film, it's because they probably don't

like the songs. John's like, "that's cool because that gets me off the

hook." These songs suck so I don't like the movie.

John Carney:

That's how a musical should be. The only musicals I hate are the ones where

I hate the music.

Will you let John

shoot your music video now?

Will you let John

shoot your music video now?

Glen Hansard:

He already has. For me the most beautiful thing about this film is that no

matter what happens John has documented Markéta's and my history. He's

documented a bunch of music I've written. It's on DVD. It's there. I'll show

it to my kids. That's it. That's the beauty of it. That's the moment.

When all the rest goes

away that's what is most important. It's funny that we're doing promo now. I

have to say it's boring, this whole idea of sitting in front of an audience

and singing our songs because we don't do this in our lives. It not

something we do at all. This is very, very new and strange and quite

enjoyable actually.

At the end of the day

when all the ink and things evaporate – because fame is measured in ink – at

least we will have this documentary that hopefully in 20 years I will take

off the shelf and show my kids and it will be like "There's your dad when he

looked good and had hair."

John, you said that

shooting on video is kind of a risk in a way. Did you think about going back

and using film?

John Carney:

No, because there are different tools for different stories. Every young

filmmaker – would you believe that some people still call me a young

filmmaker, and I love when I read it. I am a young man. Every filmmaker

wants to shoot on 35mm but it's kind of ridiculous because there are some

stories where you'd waste all your money on 35mm. You'll bring the circus

into town.

There are certain

stories that need certain approaches and this was definitely one where I

thought I don't need to use film because it was a very intimate project. For

me it was very autobiographical. It has that feel where you shouldn't be

watching what you're watching in a way; that was part of the project. This

is a bit too intimate. We were saying at the screening last night about the

scene with the woman that Glenn is watching on the laptop. That was my

girlfriend and that's actually footage that I filmed of her from seven years

ago with all the rudeness cut out.

No rudeness!

John Carney:

Yeah, the rudeness has to go. Even though the audience does know, they feel

like this is someone's home. You know when you see those movies and it's

faked and recorded and everyone is doing this when you are faking.

John Carney:

Yeah, the rudeness has to go. Even though the audience does know, they feel

like this is someone's home. You know when you see those movies and it's

faked and recorded and everyone is doing this when you are faking.

I wanted to get the

audience into the atmosphere where you were looking at something intimate

because it is a film that friends made. There is no lie. We did make it as

friends. We didn't make it to be here promoting it. So everything that

happens in the film is a bonus. The [acclaim from] Sundance is a bonus. Just

like what Glen said, if we show our kids in the future…. Plus it was made

cheaply, so if we needed to destroy it because it was rubbish [we could].

Glen Hansard:

Plus the fact that me and Markéta aren't actors. There was a lot of footage

that needed to be shot [repeatedly] to get us right. So if you were shooting

us in film you would have spent a lot of money. I really wanted to do a

black and white 16mm. John was basically like... No!

John Carney:

There's no point trying to be beautiful in this film. Just let the music and

the relationship be the beautiful part. That's all it needs to be for me

anyway.

This guitar you

play – it has survived a lot.

Glen Hansard:

Well, the uncle I was telling you about brought it for me years and years

ago. I used to play in his band and didn't get paid for it, so eventually he

brought me this as sort of a gift. I just had it for so long and it's been

my guitar so I've brought it into my professional career.

During the making of

the film, John was like "You definitely have to use your own guitar;" I was

like "Yeah, because that's what I use anyway."

It's really funny

because it's just a piece of wood and the case is worth more that the guitar

itself. It's getting pretty old and I wanted to protect it. Parts are

starting to fall off which is bugging me out because I'm not used to being

attached to things.

So where does that

leave you guys? Now that you have your acting career, is that the end of the

music?

Glen Hansard:

No. We'll make a sequel called "Three Times a Lady."

One of the best

scenes involved the two singing at the dinner table. Is that kind of

something you two lived through in real life?

One of the best

scenes involved the two singing at the dinner table. Is that kind of

something you two lived through in real life?

Glen Hansard:

Oh yeah, that's a typical evening in our lives. That's actually my flat

where we shot in. My mother is the one who sings the Irish song and all the

people in the room are friends. There were no extras in this film. We just

got all our friends to come, so actually we just threw a really big party

and John spent an hour of the party telling people to shut up while he

filmed something. It was really just a get-together with friends and family.

One great thing I love was, here was an opportunity to get all the people

you love in your life in one room that you could document forever.

John Carney:

But it's not a documentary...

Glen Hansard:

Even the extras were people from the set so basically everyone got used.

John Carney:

I spent three years in working for TV because it paid well and every extra

got paid $100; there were only three takes. So coming back to make Once

was a really great because it's was what I really thought filmmaking was

about.

Films should be about

the real world so it was great to have a situation where – because we had no

permits for shooting the opening scene [on the street] – that the actor who

played the kid that grabs Glen's busking money, he actually got chased down

the street because no one who saw it knew he was acting. I was shooting so

far down the street that no one saw him. We basically had to go rescue him

from the guys who chased him down.

-- [SPOILER ALERT] --

The end is so

bittersweet. What do you think happen to the guy and girl?

Glen Hansard:

I like to think that the guy goes back and works things out with the girl

[his former girlfriend, now living in Liverpool] because he really loves

her. This guy was kind of lonely, then this girl [Markéta] walks into his

life and then he finds him writing songs and playing the guitar, something

that he wasn't used too. She basically woke him up out of a long, long

sleep. I like to think he does the right thing and goes and gets back with

his [former] girl, but he keeps this [new] girl in his heart.

John Carney:

Why do you think the two don't end up together in the end?

John Carney:

Why do you think the two don't end up together in the end?

Glen Hansard:

Why? Because she doesn't want me.

Well you two just

have such good chemistry. I just wanted to see a happier ending.

John Carney:

That's what people are responding to in the picture. As you can see, you are

wondering why they didn't stay together.

Glen Hansard:

I think it's about her strength. The whole film is about her strength. She

basically walks up and puts it out to him. He responds by getting his shit

together and going away. She's actually left with the bad rap because even

though she goes back to her husband [we don't know what happens to her

really]. If the guy had a choice in the matter he would have been all over

her. It just never was going to happen.

She does the right

thing. We wanted to make a story that was about their romance through music.

I was just on the phone the other day talking with someone and they said

that your film was a sentimental and romantic film when it actually isn't.

To me a romance is a film where two lovers talk about themselves a lot and

what could happen. That to me is a romance. In this film they never touched

and never kissed. There's only one moment where they physically touch and

that's the end when he holds her by the piano.

So to me it's a film

with romance through music. Specifically how music and the artistic

connection between two people can be incredibly romantic. So for me it was a

no-brainer that they would never come together. Maybe a kiss – but that

would be it.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.

Features

Return to the features page.