PopEntertainment.com >

Feature

Interviews - Music >

Features Interviews F to J

> Herbie Hancock

Herbie Hancock

Herbie Hancock

New Directions

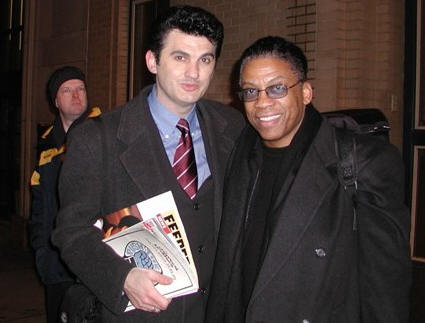

by Zoran Misetic

Copyright ©

2005 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted: February 6, 2005.

Herbie Hancock is a true

icon of modern music. His explorations of melody have transcended limitations and

genres, and at the same time he has maintained an unmistakable voice.

Hancock’s success at expanding the possibilities of melodious thought has

placed him in the annals of this century’s visionaries.

Born into a musical family in Chicago on April 12, 1940, Herbie Hancock

earned his college degree in engineering at Grinnell. He

always had a gift for composition, so despite his degree

music would become his life’s work.

Legendary jazzman Donald Byrd who brought him to New York in January of 1960 and

introduced him to Blue Note Records. Byrd also prodded

Hancock to show Mongo Santamaria his composition

“Watermelon Man” on a band break one night, leading to

Hancock’s first top ten record as a composer.

Hancock began recording for Blue Note as a band leader in May of 1962.

Even from the beginning of his career, his

records clearly chart his development and his varied musical interests.

After impressing with his own work, Hancock was part of the legendary

Miles Davis Quintet for most of the sixties.

Many years later this jazz genius is still finding himself.

Again, he is involved in

dealing with the inventive way of delivering jazz sound, working on

the extremely brave and challenging musical project; Directions In Music.

In

2002, Verve Records released Directions In Music: Celebrating John

Coltrane and Miles Davis. This project was a collaboration between

pianist Herbie Hancock, saxophonist Michael Brecker and trumpeter Roy

Hargrove. The live recording won two Grammys in 2003.

The follow-up program, Directions in Music: Our

Times, is focusing on

and exploring the themes of contemporary composers

such as Wayne Shorter, Hancock, McCoy Tyner, Chick Corea, Jaco Pastorius,

Stevie Wonder and the late Ray Charles.

The point is, just like other greats of jazz, the players in

Direction In Music

don’t stop experimenting. That’s

the name of the game when comes to genius of Herbie Hancock.

How

did music become your life?

How

did music become your life?

Well… Not really my life, but instead of that I should say,

a good part of my

life. Fact is that I played piano and performed, as a young kid, a Mozart

piano concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra . Don’t forget I was only

eleven-years-old and to

be on the stage at that age had tremendous impact on me. Basically love for

classical music and performing as a kid on the big stage probably led

toward this decision, which meant that music is going to be my big love but

also my profession.

Yeah, but when did you really get

gripped by jazz

?

Oh, my God, that was in my high school days. That’s when I started to play

jazz and at that time, I was very much influenced by Oscar Peterson and Bill

Evans. But also I know at that time that jazz music can and should have full

freedom to sound different… more inventive and confusing at same time.

When I started to play jazz, I found myself dealing with interest which was

directly pointed toward electronic science. I got double major in music and

electrical engineering. Somehow, don’t ask me how, many years later that

helped me to create my own sound, my own approach to jazz music.

Did

you find New York City to be crucial for dramatic

development of your jazz career?

No

doubt. It was crucial for my jazz development. Well, I was helped by Donald

Byrd to basically experience that all beauty of the NYC jazz scene. He gave

to me that initial kick to move forward. First he asked me to join to his

group and after that he introduced me to Alfred [Lion]

from Blue Note Records. In the beginning I was doing, more or less, session

work with guys like Phil Woods and Oliver Nelson, but after probably year and

half or let’s say two years, I signed to the Blue Note Records as a solo

artist.

That was time of your Takin’ Off album and you really “took off

“with that album.

That’s correct. I mean, “Watermelon Man” from that album became instant hit

at jazz and R&B radio and that gave me real recognition in the jazz

community. That was one of the reasons why Miles showed interest in me.

Are

you talking about period when you joined to his Quintet?

Yes. That’s exactly what I meant. Same year I had my solo album out and I

got invited by Miles to join to Miles Davis Quintet. 1963, was definitely

good year for me. Brought to me tremendous experience and let’s face it,

money.

How

long did you stay with Miles Davis?

I

spent five years, at least, working with Miles.

Together, we recorded ESP, Nefertiti, Sorcerer --

and I can tell you; each of these albums instantly became jazz classics.

Hey, we had Wayne Shorter playing tenor sax, Ron [Carter] on bass, Tony

Williams played drums. That was great band we had.

But

after these five years you still didn’t break loose completely from Miles

Davis?

But

after these five years you still didn’t break loose completely from Miles

Davis?

That’s true. We continued to work together and he invited me to take part on

his crucial recordings such as In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew. Again,

Miles was very instrumental in my jazz career. He was free spirit and he

basically allowed me to go ahead experimental approach to jazz sound.

You

had so many hit records; either your solo records or records that you

recorded with other musicians.

How did you react in 1994 when British hip hop group called Us3 sampled your

classic “Cantaloupe Island” for a track called “Cantaloop

(Flip Fantasia)”?

I

was pleased with the way this band took a spin on “Cantaloupe Island.” At

same time, I was also positively surprised that

their version became a huge international hit. I can tell you, these guys

made lots of the money for Blue Note. It was interesting period in my life

because sometimes in my concerts

the public expected from me to play that

version instead of my original. (laughs)

Do you have high expectations from your new project

Directions in

Music: Our Times?

I

always have high expectations when comes to my approach of shaping jazz

sound. Either live shows or studio recordings, I am always expecting from

myself to give the maximum. On this particular project, I can tell you that I

get great satisfaction from the fact that I am working with talented

musicians who are taking this project down it’s own compositional path. It’s

really good stuff.

The night was cold and short, but

the warm conversation with Herbie Hancock

explained, at least to me, that it’s possible to still

have great interest,

love and desire for something that you

have done for the last

fifty years. Or, as another

musical legend may have put it, Herbie Be Good.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.

Features

Return to the features page