There are certain

songs that feel like they were born as classics: the world knew and

loved them from their release date. Immediate standards like

"Something," "Bridge Over Troubled Water," "My Girl" and "Imagine" were

fully formed in the pop culture firmament from the very start.

Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" took a much rockier road to become a musical masterpiece.

The song was a pretty unnoticed album track on Leonard Cohen's 1984

Various Positions record – the one album in Cohen's forty-some year

career that was rejected by his long-time record label Columbia. The

song troubled Cohen so greatly that he wrote 80 verses trying to

get it right and continued experimenting with it in concert for decades after

it was recorded.

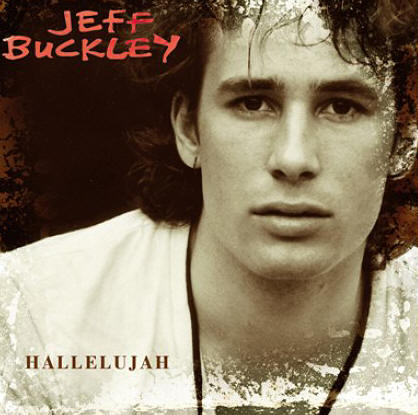

It took twenty years

and an eventual hundreds of cover versions – most vitally the ethereal

cover by the tragically short-lived singer Jeff Buckley – for "Hallelujah" to attain the popular ubiquity that it has achieved in the

past decade or so. From the Olympics to Shrek to American

Idol to concerts for the survivors of the World Trade Center

disaster, Haiti and Hurricane Sandy: when a song is needed to convey a sense of

tragedy, hope or faith, chances are good that "Hallelujah" will be

performed.

Many of the biggest

names in music – including Bono, Bob Dylan, Justin Timberlake,

Neil Diamond and Jon Bon Jovi –

have taken a stab at the song. The song is so malleable that acts from

most styles and genres can feel equally comfortable within the gorgeous

melody and poetic lyrics. The fact that there is a long-standing

tradition that verses can be swapped out, moved or even ignored has

created a pop masterpiece that literally can be all things to all

people.

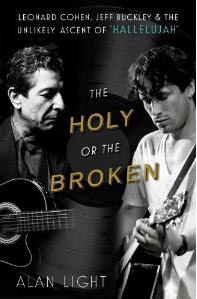

Longtime music

journalist Alan Light (The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Spin)

was fascinated by the unusual journey in which the song has ingratiated

itself into so many hearts. In his fascinating new book The

Holy or the Broken – Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley & the Unlikely Ascent

of "Hallelujah" (Atria Books), Light takes a detailed look at the

strange and troubled road that led to this iconic pop culture treasure.

Soon after the book's

release, Light gave us a call to discuss his book and the cult of

"Hallelujah."

So

why "Hallelujah?" What is it about that song that you feel has captured

people?

So

why "Hallelujah?" What is it about that song that you feel has captured

people?

There's not

one easy answer to why the song resonates. It reaches some very basic

and very universal emotions. First of all, when you're dealing

with something like a Leonard Cohen song, it's very easy to get caught

up in the poetry and the lyrics and the intricacy of the imagery – all

of which are very significant to the impact and the longevity of

the song. But I think people respond to songs first for melodies, moods

and feelings. The elemental, irresistible and very singable melody

at the heart of this song is something that we've seen everybody from opera

singers to Willie Nelson can sing convincingly, whatever your range.

Then also, the feeling and the universality of this word "Hallelujah"

and this idea that goes with it. It's the kind of spirituality that

people are hungry for, are trying to find in the world. Especially as

they go outside of more organized religion, when they find an

experience it feels significant for them like this. That idea of "Hallelujah," giving praise and thanks and finding that kind of spirit

and survival at difficult times. A friend, the cantor at a synagogue in

New Jersey, in the book she says early in her career somebody told her

that if you are singing in interfaith settings or you are singing

outside of your synagogue, any song with "Hallelujah"

in it always

works. That's an idea that cuts across different faiths, different

beliefs, whatever. Everybody kind of gets that. So, I think it's first

of all those things and then over time [it became] the litmus of the

language and the multiple meanings that the song can be imbued with.

Unlike an

overnight smash like, say, "Yesterday," "Hallelujah"Ā¯ had a fascinating

progression, starting out completely obscure and then slowly but surely

engraining itself into the public conscious. How important do you think

it is that the song had sort of a slow burn?

First of all, it was

that trajectory that made me interested in exploring the song. I cannot

think of another song that had a comparable experience. Anything that's

up in that altitude, songs like "Bridge Over Troubled Water" or

"Imagine," people got right away that those were important songs. They

were big hits. Obviously, their meaning changed over time, but there

was this huge splash and then everybody was aware of them.

"Hallelujah," when Leonard turned

in the album the song was on, his label rejected it. Columbia didn't

put the album out. Then when it came out on an indie label a little

later, nobody noticed the song. The review in Rolling Stone was

a nice review, but it didn't mention "Hallelujah." So this song starts

not just under the radar, but way off the radar. (laughs) No

one knew it was there. As you said, it's the fact that it [appeared]

slowly but surely. It was never a hit. It

was never one thing where everybody discovers this song. It was a

gradual build of momentum that kind of snowballed, in fact, from

different covers and different versions and different uses. What it

meant was even still you were in kind of a secret club when you know

about this song. Even though it's become one of the best-known songs in

the world, it still feels like a secret that you've been let in on, that

you've discovered. This is not some big pop song that everybody knows,

even if it is a big pop song that everybody knows. Retaining that

feeling certainly has been important to the longevity of this

experience.

As a writer, how

daunting was it to take on the idea of doing an entire book about a

single song?

What was fun about it

was that I wasn't fully convinced at any stage that it was going to

work. I had this idea that obviously something really fascinating had

gone on with this song and maybe that was worth spending some time

with. Writing the book proposal was really an exercise in like: Okay,

does it seem like there is really enough going on here? What was great

was that around every corner was more. The story got richer and

richer. You see how this version leads to that version. What was

really striking was that everybody who has sung this song has ideas

about it. You expect that Bono, or k.d. lang, or some of these people

will have profound things to say about a song, but you don't necessarily

think that the American Idol contestants or Jon Bon Jovi or some

of the people that you might think: "Eh, my manager told me to sing the

song, so I sang the song." What I really found was that nobody sings

this song blindly. They are all very aware of what it means and how

important it is. The kind of legacy that you are a part of when you are

singing this. They don't all have amazing thoughts about it, but they

certainly all thought about it. So, it just kept opening up in more and

more directions until it felt like there was enough to sustain a full

book around it.

Leonard

Cohen only does very limited interviews and of course Jeff Buckley is no

longer around. Did the inability to talk with them make the writing of

the book harder?

Leonard

Cohen only does very limited interviews and of course Jeff Buckley is no

longer around. Did the inability to talk with them make the writing of

the book harder?

No. I had no

expectations that Leonard was going to talk about it. Like you said, he

hardly does any interviews, and also I understand: What does he have to

gain with this song, with all of the aura around it, when tells me I

thought of that line when I was brushing my teeth? (laughs)

What does that contribute to the legacy of the song? So, I really went

to him just asking for his blessing and his approval and that I could

tell people that he was cool with the fact that I was doing this. And,

honestly, there's a couple of stories over the years that he's told

about the song and I feel like that's what he has to say about it. If I

don't get those stories brand new from him but have them, they are

there. They are out there and those can represent that idea. In a way,

the benefit of that was that the book could have gotten too top-heavy as

a Leonard and Jeff co-biography or something. Knowing that I really

wanted it to be the story of the song, I didn't want to spend too much

time with those two guys. You want to tell the story and set it up, and

obviously present these most pivotal versions and how everything else

bounces off of them. In a way, the fact that those had to be a little

more second hand – I talked to the producers of both versions, the

engineers who were around the sessions – but it's not a creation story.

Creation is actually very quiet. The important part is everything that

has happened since. I think in some ways that freed my hands up to feel

like, okay, I can talk about those guys in a finite way and keep things

moving into everything else that has happened.

It seems that John

Cale is sort of the unsung hero to the "Hallelujah" story. Were you

surprised by how important his version of the song ended up in the

song's ascension?

I'm not surprised, in

that I had known his version and known what his was... his re-edit and

rearranging of the song, what that did. I certainly didn't know that it

was actually very directly, that Jeff Buckley learned John Cale's version

of the song. He hadn't heard Leonard Cohen's version when he first

started performing "Hallelujah." Which makes a lot of sense, when you

listen to them. You hear that what John Cale did was strip the song

down musically and emotionally and take it away from this sort of

grander spiritual aspiring of the original recording by Leonard. Do it

just as voice and solo piano. Speed it up a little. Make it feel more

human, more edgy. I think what his edit and then Jeff's version did is

really make it a younger person's song. When Leonard recorded it, he

was 50 years old, he was at a certain point in his career, and it really

has a feeling of looking back on the lessons learned in surviving the

challenges of life. It has that almost elegiac feel to it. Those are

not lyrics that a 24-year-old Jeff Buckley would have been convincing

singing. By doing Cale's version, it's much more present tense. Much

more about learning about heartbreak and pain as it is happening to

you. Seeing what it is that life throws at you and how you have to

press on and survive through that and still hold on to hope and faith,

whatever that means. I think Cale's version obviously is critical to

the direction that the song took. Leonard wrote it to the world.

Leonard wrote it, John Cale edited it, then Buckley was the vehicle to

perform that out to the world.

You

say in the book that Leonard Cohen wrote about 80 verses of

"Hallelujah," though basically it seems there are about seven that are

used most often. Were you able to see any of the additional verses when

researching this book?

You

say in the book that Leonard Cohen wrote about 80 verses of

"Hallelujah," though basically it seems there are about seven that are

used most often. Were you able to see any of the additional verses when

researching this book?

I was not. I raised

it at one point, with no expectations. Several

things... The good part of that story is, there is one sort of sub-theme

of this story, that during the first part of the story, the discovery

and popularization of the song around the turn of the century, were the

years when Leonard's manager was stealing all his money and ultimately

disappeared with millions of his dollars and a bunch of his stuff –

including the notebooks that the "Hallelujah" drafts were contained in.

Happily, when she came to trial last year – as a harassment trial – he

got back a lot of his stuff, including the "Hallelujah" notebooks. So

they are back in his possession. But it's obviously a song that is

particularly important to Leonard. He has talked a lot about the

torture that "Hallelujah" caused him and how difficult it was to figure

out what the song was and where to stop. That's not a unique

process for him. Many of his songs go through lots and lots of drafts.

Lots and lots of extra verses and bit parts and things that extend for

years and years. So I think ultimately he has got to decide if that

all goes in a University archives anywhere or if he publishes any of

that remains to be seen, but he did not open the other 70 verses to me.

And, fair enough. Things don't come out for a reason.

Can you think of

any other song where people can just swap in and out or rearrange

different verses or lyrics to suit their own meaning?

It's really

unique. I'm sure that there are, especially if you think about national

anthems or more civic kinds of songs. There are other verses to

"The Star-Spangled Banner." Stuff like that. But it's hard to think of

another pop song where there is permission to alter it in quite the same

way. It certainly has been very much to the song's service that you can

turn up or turn down different elements. You can take what you hear in

"Hallelujah" and make that what your version of the song is. If things

don't seem appropriate to sing in a church service, it's okay to drop

those verses. If you want to concentrate on the romance and heartbreak

side of it, you can dial that part up. You think about "Imagine." I

say in the book, Yoko Ono says she gets requests every week from people

who want to record "Imagine," but they just want to change that one

line. They want to change the "Imagine no religion" line, then they want to

do it. She says, it's not for me to authorize that. It's not for me to

say that you can change meanings that way. That's one line in the

song. With this song, it's been clear for many years to sing whatever

verses you want. Take whichever lines you want. I think it got so

removed from Leonard's original experience that he kind of watches it

like everybody else. Sees where it's going to go. Lets it take its

own life.

I did a biography

of Tom Waits, and at one point Solomon Burke was recording one of his

songs but wanted to change a lyric because it was not religious enough

and his producers were horrified and told him you just don't rewrite Tom

Waits. In the end, Waits okayed it, but Leonard is held in similar

stead as a lyricist, so I find it fascinating that people do change his

song up so easily.

Right. They would be

more protective. But I think, again, it was such a struggle for Leonard

to finalize this song. After it came out, immediately when he was

touring he was changing lyrics and switching up verses. The live

version he put out from recordings that were right after the Various

Positions album came out, different verses in a different order.

Whether it was his disappointment at how little response the song got in

the first place or whether he just wasn't fully satisfied with it yet,

he himself didn't view it as a fixed text at that point. So, I guess at

that point he said, well, let's see what it is that people respond to

and what they want to do with it.

Who

were some of the most important people for you to talk to? Also, were

there people you were surprised to get to discuss "Hallelujah"¯ with you?

Who

were some of the most important people for you to talk to? Also, were

there people you were surprised to get to discuss "Hallelujah"¯ with you?

The things that were

gratifying were first of all how everybody really did want to talk about

it. Justin Timberlake and Bono and Jon Bon Jovi, all the biggest stars

who've done it, all were very open to the idea of talking about this

song and their performance. As I said, everybody across the board had

things to say about it and clearly had thought about the song. That was

great, because you just don't know. What was in some ways even more

gratifying was just talking to regular people about how

they've used it in their lives – in weddings and funerals and religious

services and all of the ways that the song has become so embedded in

people's actual experiences. It's so easy for us to get cynical about

music now and think it's so commoditized and it doesn't mean what it

used to. It's not important the way that it used to be. To hear what

this song means to people and of these pivotal moments that they turn to

it and the reasons that they turn to it, that was a really powerful

thing for me to hear. Music really does still matter in that way. It

really does still play such a crucial role in real life. You sometimes

forget about that these days. (laughs) It was really good to

hear all of that. The important versions... there are

different kinds of importance. Obviously I did want to talk to the

people around Leonard and Jeff's recordings, just to hear about what

those sessions were and how they got the versions that they did. Then

it was important to talk to the director of Shrek, to hear about

how it ended up in, of all unlikely places, an animated kids'

movie. It was important to talk to some of the American Idol and

X Factor contestants, to hear about what it was to have this song

in that context that put it in front of millions and millions more

people. Obviously, again, the people like Bono and Timberlake and

people whose recordings or performances really propelled it to a whole

other kind of audience. To talk to k.d. lang about not just her

recording, but also playing it at the Winter Olympics opening ceremonies

and having it go out to hundreds of millions of people across the world

in a performance like that. Each of those brick by brick were building

what it was that this story is about.

Were there some

other people you would have like to have talked to that you could not

get through to?

The person I really

most wish I could have spoken to was Simon Cowell. (laughs)

Whatever one thinks of him, he put himself out very strongly behind this

song. He's used it multiple times in multiple of his shows, in several

seasons of Idol and of X Factor. For all that you think

about kind of the sideshow with him, I thought here's a chance to

actually talk about music and he might welcome that. But, for whatever

reason, I couldn't get to him. If there is one I most regret in some

ways, it's him, but most of the people I was trying to get to were

really pretty good about it. It takes time getting onto Bono's

schedule, but eventually you get there.

Most

Leonard Cohen fans would be hard pressed to name "Hallelujah" even as

their favorite Cohen song. Do you think it is his best work? What are

some of your other favorite songs?

Most

Leonard Cohen fans would be hard pressed to name "Hallelujah" even as

their favorite Cohen song. Do you think it is his best work? What are

some of your other favorite songs?

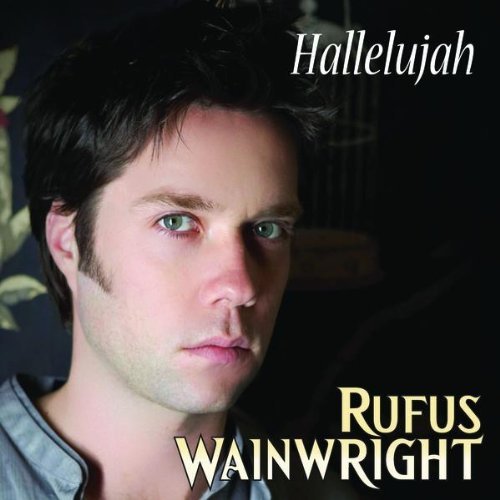

Best is a tough

call. I find it interesting that when Rolling Stone had Rufus

Wainwright give his ten favorite Leonard Cohen songs for some special

issue, "Hallelujah" didn't make his top ten. Now, maybe he's just tired

of singing the thing. I don't know. I think a lot of devoted Cohen

fans would probably agree with that. My own favorites? "Tower of Song" is a song that I absolutely love. I think it's a

perfect piece of writing. "Anthem" is a tremendous song. "Bird on a Wire" is a really

good song. But I think when you think of each of those, you may think

of ways they are better in terms of the perfection of the imagery and

the intricacy and the precision. They are remarkable pieces of writing,

but you can also see how those songs are not going to resonate

universally the way that "Hallelujah" does. They don't have quite that

melody, that hook, and again, this kind of general spiritual sense that

the chorus gives you that makes this a different kind of a song. You

understand why it is that this one hits in a way that other stuff that

he's done does not. In some ways, the things that are less imperfect in

the song are things that have ultimately been to its advantage. A

little bit of the ambiguity and the haziness of the lyric and the way

that it shifts perspective and it's not always exactly clear what is

going on in the verses. What we were saying before, I think that allows

for some more interpretation, some more malleability and ability to make

the song mean what you want it to mean, however fair or not fair it is.

It leaves the door open a little bit in a way that not all of his stuff

would do.

What are some of

the best recordings of "Hallelujah?"

It's kind of a punt,

but when asked for my favorite, my answer is always the way that Leonard

sings it now, on the last couple of tours.

I

agree, I think his Live in London

version may be my favorite.

I

agree, I think his Live in London

version may be my favorite.

Yeah. And the

version from Coachella that is on Songs From the Road. That's a

pretty remarkable version. It distills a lot of what has been

learned about this song over all the years and all the different edits.

How he now puts the verses together. I think there is something very

special in that. k.d. lang does a pretty remarkable version.

Her voice is a pretty powerful match to this song, in a different

kind of an effect than some of the others, it's a really good one. The

other one that was great for me to go back to, maybe because it's just

so easy to get caught up in the words, is an instrumental version by a

ukulele player named Jake Shimabukuro, who is kind of the Jimi Hendrix

of the ukulele. He does it as an instrumental. When I talked to him,

he's like, "This song isn't about the words at all for me. It's about

the feeling of the notes and that melody line." If nothing else, it was

good for me to regularly go back to that as opposed to thinking, well do

they do this verse or that verse? What's the jigsaw puzzle of the

lyrics from this version to that version? Just to hear this is what

this song is, this is what the melody is, this is what it sounds like.

That became a very powerful thing for me to have.

What are some of

the worst?

There's not that

many. I think that as somebody says in the book, if you just stand

there and deliver the song, it doesn't fail very often. (laughs)

Look, I have no issue with the idea of Susan Boyle recording this song,

but I think that the edit that she did for her Christmas record is such

a butchering. It literally cuts off in the middle of a verse. It

doesn't make any sense. (laughs again) That is a difficult one

to get through. It's clear she's just looking for the excuse to get to

the chorus as fast as she can. Sing "Hallelujah" over and over again

and not have to bother with the rest of the song.

Right.

And it has always sort of amused me that "Hallelujah" has tended to make

it onto holiday albums, because there is nothing the least bit

Christmas-y about it beyond the fact that it has some religious imagery.

Right.

And it has always sort of amused me that "Hallelujah" has tended to make

it onto holiday albums, because there is nothing the least bit

Christmas-y about it beyond the fact that it has some religious imagery.

No. But that's

enough [for some people]. That feeling that it can be seasonal or

whatever. So that one. The other one that is funny to talk about is

Bono's recording. When he did it as a solo recording on a Leonard

tribute record [Tower of Song] in the 90s, he did this sort of

trip hop electronic version where he whispers the lyrics and sings this

falsetto chorus. It's just a train wreck. It's always such an

incredible disappointment from someone you think more than anybody could

get inside a song like this. It's just a mess. So I talked to him,

after some time to chase him down. It really was very funny, because he

got on the phone and said, "Hi Alan, it's Bono. I couldn't remember why

I agreed to do this interview. Then I remembered it's because I have to

apologize to everybody." (laughs) He proceeded to say,

"I know that version that I did is just terrible. I know what I

was trying to do. I know what the experiment was, but I never

should have put it out. This song is so important to me and I just

kind of botched my chance at it." I was relieved, because I had been writing about how bad

his version was and thought, oh, well, if he gives me some great defense

of it I'm going to have to rework that entire section. Instantly he

copped to why it just didn't work at all and how embarrassed he was

about that. But he's made his peace with it. U2 were treating

"Hallelujah" as part of the encore on the last two tours that they did,

so I guess he's gotten over that experience and he can get up there and

do it again.

As you mentioned

in the book, a tiny bit of "Hallelujah" backlash has set in, now that

it's been on American Idol and even Adam Sandler just parodied

it. Do you think the song will settle in now, or do you think it will

continue to grow to become even more of a standard?

The Sandler thing was

funny, because I say in the book that I'm waiting for somebody to do the

parody. It was sort of past time, given how long this song has been

taken so seriously and so solemnly. I was waiting for Weird Al [Yankovic]

or putting it in a Judd Apatow movie or, I don't know, something to pop

the bubble a little bit. The week after my book comes out, Adam Sandler

gets up at this Hurricane [Sandy] Benefit and does his parody version,

which on the one hand vindicated me and on the other hand made my book

out of date instantly. But I laughed at what he did with it. It's a

tribute to... you know, you have to be confident that everybody knows a

song if you're going to get up and make fun of it in a setting that goes

out to that many people. It's funny, people heard it and it was, okay,

now maybe people are going to back off. They'll give the song a rest

for a little while. But two days after that horribly were the shootings

in Newtown [CT] and instantly, when people needed that emotion or

something to do that work again, "Hallelujah"¯ was at the memorials for a

bunch of kids. The opening of The Voice the next week the judges

and the contestants all sang "Hallelujah" holding the names and ages of

the victims on cards in front of them. It wasn't even 48 hours after Sandler's thing and the song was right back in that kind of use again.

So, I don't think it's over. I think that maybe there is a finite life

cycle in some ways. I talked to Paul Simon and he said he never

expected that "Bridge Over Troubled Water" was going to become what it

became, but he watched it turn into that kind of a song that is always

there and always around. Then he watched "Hallelujah" come up and be

the next song that did that. It's tough to say that somebody else won't

write a song that connects in a similar way and become the go-to for a

while. But I think until then, this is going to stick around for now.