Copyright ©2006 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

August 16, 2006.

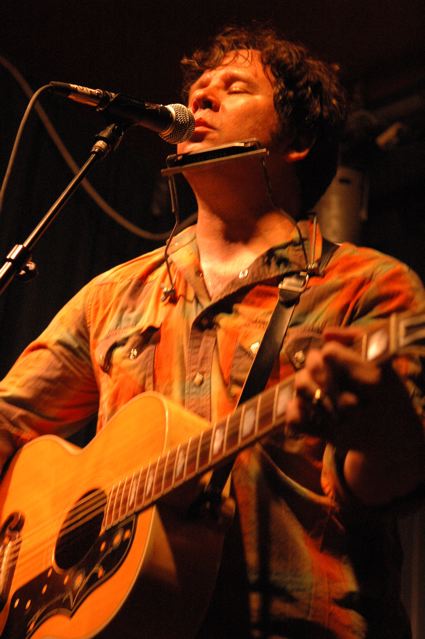

Grant-Lee Phillips was the next big thing

for so long that now it almost seems fascinating that he has been able to

stay so humble. As the leader of Grant Lee Buffalo – one of the 90s big

buzz bands that never quite seemed to explode – Phillips was pictured as

the face of indie rock on a major label. Buffalo released four albums for

Slash/Warner Bros. in the decade, including Fuzzy

(1993), Mighty Joe Moon

(1994), Copperopolis (1996) and

Jubilee (1999). However, except for a

couple of minor hit singles with “Fuzzy” and the gorgeous ballad

“Mockingbirds,” Grant Lee Buffalo never got the recognition everyone

expected.

After four Buffalo albums were critically beloved but did not seem

to catch on, Phillips requested his release from his contract and decided

to work as a solo artist. His first solo album in 2000 was Ladies’

Love Oracle.

He

has since recorded Mobilize (2001)

and Virginia Creeper (2004) – all

of which have received the kind of critical adoration that used to

accompany his old band, but without all that next-big-thing pressure. Now,

Phillips feels perfectly comfortable doing small concerts around the

country, sharing the driving to the shows with his drummer and setting up

his own equipment. He no longer has any interest in playing the future

rock star, his life is more like that of his fun side project; doing

regular cameos on the popular TV series Gilmore Girls

as The Stars Hollow Troubadour.

Phillips’ latest album is something of a departure for the renowned

songwriter. On nineteeneighties,

Phillips deconstructs eleven songs by some of the biggest names in 80s

alternative music, including “Love My Way” by the Psychedelic Furs, “so.

central rain (I’m Sorry)” by REM, “Boys Don’t Cry” by the Cure, “Last

Night I Dreamt Somebody Loved Me” by the Smiths, “Wave of Mutilation” by

the Pixies and “Under the Milky Way” by the Church. On the album, Phillips

strips back these songs to their acoustic essence – in a way reinventing

these seminal tunes.

While on tour for the new album, Grant was nice enough to sit down

with us to discuss the project and his career.

How did you originally get into music?

Wow, how did I get into music? Boy, oh,

boy, I’ll try to give you the most concise answer. I got a Sears guitar

for Christmas. I believe I was thirteen years old. Made all sorts of

noises with it. Slept with the thing. Played it non-stop. Then about a

year later I learned how to tune it. (laughs)

But I had a good year just sort of exploring with it. Learned a few

songs, a few covers, back in that first year. What I found almost as

immediately as I learned a chord or two, I learned how to write songs. By

the time I turned fifteen or so I’d worked up a body of my own songs and

was playing them for kids in school. Then that became a pursuit at that

time – to put a band together and one day leave my hometown of Stockton

and head down south to Hollywood.

How did you get together with Grant Lee Buffalo?

Grant Lee Buffalo came together from the

ashes of another band called Shiva Burlesque. That was sort of a glammy,

post-sixties psychedelia kind of thing. Influenced by the Doors and

William S. Burroughs and all points in between. I wasn’t the singer in

that band. I was really the guitar player and a co-songwriter. Along

with me there was drummer Joey Peters and later bassist Paul Kimble. The

three of us were the nucleus of Grant Lee Buffalo. When that band –

Burlesque – came to an end in the late 80s, there we were. I had again

sort of stockpiled a number of songs that never were divulged during the

process of the previous group. That’s when I recorded “Fuzzy” and

probably fifteen or twenty other songs that ultimately got us signed to

Slash Records.

Grant

Lee Buffalo released four critically acclaimed CDs. Rolling Stone even

named you Male Vocalist of the Year in 1996. Was it frustrating that all

that acclaim never really translated to sales?

Grant

Lee Buffalo released four critically acclaimed CDs. Rolling Stone even

named you Male Vocalist of the Year in 1996. Was it frustrating that all

that acclaim never really translated to sales?

Well, yeah. I can never be exactly sure

what exactly the band sold. I mean, obviously it sold well enough that

they kept picking up the option for a long while and probably would have

continued. It just became quite a different situation for me though by

the time we got to the last album, Jubilee,

which was the fourth and final Buffalo

album. Really, what had started as a three piece was reduced to myself

and the drummer. Being the songwriter and the singer, it started to make

less and less sense to do this as band to begin with. I don’t know, I

think there were a lot of things that were kind of reaching their peak at

that point. The label, Warner Brothers, for instance, had gone through

five different Presidents while we were there. It was very strange.

That’s continued. I mean, I don’t know that Warner's has fared so well,

even over the last five years. It’s the kind of thing that I could

certainly spend an evening pondering all of it, but I don’t know how far I

would get in terms of coming up with real answers. Why a band hits the

big time or not… I think for an artist like myself it’s almost as though

it’s a better thing to stretch it out. Longevity is perhaps a much better

reward. The fact that I’m playing music today. A lot of those that were

signed to Slash and Warner's and other labels at the time are no longer

playing music these days. For me, it kind of goes hand-in-hand with

living. I guess because I always had heroes that took their music with

them, you know? People like Willie Nelson or – a lot of the country guys,

actually. Or some of the original bluesmen. I’ve seen Lightning Hopkins

selling his own records sitting at the edge of a stage here in Chicago –

it couldn’t have been twenty years ago. Those things made an impression

on me. That it’s not always about the radio game. That’s one little

piece of the puzzle. Sometimes it’s a very large piece of the puzzle, but

it’s not the only one.

You have now released four solo CDs. How is working with a smaller label

like Rounder different than a major like Slash/Warner?

The situation with Zoë/Rounder is good

for an artist like me because they have the plumbing laid out to get the

albums. Where they need to be – which these days has become more about

the internet than the record stores, I’d dare to say. Record stores are

struggling. But they print the records up. They hire the publicist.

They distribute them. All of that machinery which I could take on by

myself, but it does defuse some of my energy to do all that. There’s a

great deal of freedom working with a smaller label. It’s easier to get

from point A to point B. Here are your marching orders – all you have to

do is go right down the hall and drop this CD off. (laughs)

Sometimes that becomes a lot more convoluted at a large corporation. You

can kind of see it in all walks of business. I think it’s certainly true

of the record industry.

It's weird, but with all you've done,

now

you may be best known as the Stars Hollow Troubadour. How did you get

involved in Gilmore Girls?

It's weird, but with all you've done,

now

you may be best known as the Stars Hollow Troubadour. How did you get

involved in Gilmore Girls?

(laughs) You know, the Gilmore

Girls thing is a real treat for me. It’s

something that developed because Amy Sherman-Palladino and her husband

Daniel were fans of Grant Lee Buffalo’s and fans of mine. They had been

coming to the shows in Los Angeles and simply asked if I’d be interested

in making a cameo on the show. I did and we hit it off really well and it

kind of snowballed from there. I’m not a constantly recurring character,

but I’ve been on the show some thirty times. Sometimes it’s a case of

strumming a song underneath a streetlamp. (chuckles)

Sometimes I have a bigger chunk to pull off, lines and all that stuff. It

definitely allows me to use some acting muscles that I might not normally

use.

The

troubadour sometimes plays acoustic versions of old songs – I remember you

once doing “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” – did that sort of inspire the

new album, or was this an idea you’d been toying with for a while?

(laughs) I hadn’t thought about that,

but you know, it’s a possibility. That was a request of theirs. They

sort of timidly called me up and said, “Do you think the troubadour would

cover ‘Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go?’” (laughs)

After I picked myself off the floor from

choking in my own laughter, I said, yeah, sure. So we went for it.

They’ve been known to challenge me a few times with that kind of stuff.

The covers record kind of came out of doing little trips by myself,

acoustically and sitting in the hotel room and working out the chords to

“Under the Milky Way” so that I had something new to throw into my set

that night, just for the fun of it. I’ve always loved that process of

taking songs apart and seeing how they work. For every song that I learn

how to play, I tend to write three other songs. It’s a bit like that

axiom; the more you read, the more you write.

As a respected songwriter, is it at all weird doing an album that’s

entirely other people’s work?

As a respected songwriter, is it at all weird doing an album that’s

entirely other people’s work?

No, it’s really just a very satisfying

pursuit. It allows me to tackle songs as I would my own, but relieved of

laying my heart on the chopping block – whatever it is that I bring to the

plate. I think you find that your thumbprint and your choices are evident

in other ways. Song selection and how you deal with those songs. I’m

currently working on another album which I perceive coming out next year.

This was just something that was fun to do, something I’ve wanted to do

for some time. As time goes on, I’m going to be much more apt to leap

into the fire when on a whim. That’s sort of what this album is. It’s

very whimsical. High time to follow that path. It’s a bit too

self-conscious and safe in our business.

There was a really interesting collection of songs on the album. While

you did music from some of the greatest eighties alt bands, only “Under

the Milky Way” and maybe “Love My Way” could be considered hit singles in

their original incarnations. How did you decide early on that you didn’t

want to do the more obvious hits of the era – like say, “Don’t You Want

Me” or “Hungry like the Wolf?”

I mean the irony of it was these were the

most obvious songs to me. This was like the radio being transmitted to my

head. Only when I had really finished the album did I peruse through the

old Billboard charts online and

was sort of awed to see that none of these were in the top 10, or maybe

even the top 40. In Australia, where the Church are from, they’re like,

oh yeah, the Church. They never really cracked it over here, you know?

But they were somewhat successful in the US. It’s more like the 80s that

I remember. I kind of like that. I think now, more than ever, people are

able to be in their own sort of time bubble. I see it in my neighborhood,

kids who are dressed as mods. I’m thinking, wow that’s great. I wonder,

did they just rent Quadrophenia

and went out and got a scooter? But that’s where they live. They’re in

that era. (laughs)

You

also didn’t necessarily pick the obvious songs in any of these band’s

catalogues – for example most people when they think of Joy Division think

of “Love Will Tear Us Apart” or “She’s Lost Control” and you did “The

Eternal.” While “So.

Central

Rain” is an amazing song; it’s not the first

thing people think of when you mention REM. How did you decide on the

songs and were you determined to mine deeper into the songbooks?

You know, again, it’s just these are the

songs that leapt out at me, that kind of struck a chord with me most.

It’s probably always been the case. Back when albums were two sided, I

probably always had greater faith in the back side of the album. I kind

of realized that’s where the real diamonds are hidden.

Eighties songs are known for their production – even indies like you have

chosen, things like “Boys Don’t Cry” or “Age of Consent.” How do you

think a cut-down acoustic background adds to these songs?

Yeah, you’re right. I realize the

production was so much a part of that era. Even so with the alternative

stuff. Through my extracting the song from the production and the style,

you would hear the song in a new way. That was my hope. You would hear

the lyric. You would get a sense of the chord changes and have a more

intimate exchange with the song. So for the most part, I simply went

about removing parts. Subtracting, you know? Only in the case of Robyn

Hitchcock’s “I Often Dream of Trains” did I take a sort of opposite

approach, because Robyn’s work is typically more minimal. It was a good

exercise. I have a hunch that it has already affected me in terms of my

own production and how I think about my own songs. Sometimes you find

perspective when you’re not looking for it by doing this type of thing.

How do you think bands like The Pixies, the Smiths, Echo and the Bunnymen

and others you have covered here have influenced today’s bands?

How do you think bands like The Pixies, the Smiths, Echo and the Bunnymen

and others you have covered here have influenced today’s bands?

Oh, goodness. Quite a few bands are

vocal about this, how they have been influenced. You can certainly hear

it, even if they weren’t willing to cop up. You hear shades of the Fall

in the Strokes. You hear the Buzzcocks and other things in Franz

Ferdinand. I think there’s a whole generation of newer bands that

obviously have pretty cool record collections. Thank God, because they

could definitely been equally influenced by Michael Jackson. And not the

good stuff.

One

thing that is great about the alt bands of the 80s is that they weren’t

afraid to have a tune. A few years ago it was something of a sell-out for

a rock band to have a melody. Why do you think the world is so ready for

more melodic rock?

Yeah, you’re right. That’s really true. I think there were a bunch of

bands because – I don’t know, I guess the time they grew out of – some of

the post-punk bands were actually quite tuneful and were trying to figure

out how to cram it all into that format, but really pushing the envelope.

The Buzzcocks are certainly the ones that come to mind. They’re so darn

tuneful. Really energetic. And the Pretenders. There’s a long list of

them. I think it’s very idealistic, that notion that you can offer the

public something quite different and you have faith that they are going to

get it. I think too often labels and radio promotion have a way of short

changing the listening audience. So everything kind of occurs at a

snail’s pace. Things get signed because they sound exactly like something

else. Things get played because they sound a bit like this or that. No

real willingness to throw the dice. It’s got to change. I think the

internet is probably the new frontier in that way.

In the songs you chose for the album, when the songs turn to love, a lot

of the relationships are in trouble or dying like in “Age of Consent,”

“So. Central Rain” and “Last Night I Dreamed Someone Loved Me.” As a

singer and songwriter, do you find sad songs more interesting than happy

ones?

In the songs you chose for the album, when the songs turn to love, a lot

of the relationships are in trouble or dying like in “Age of Consent,”

“So. Central Rain” and “Last Night I Dreamed Someone Loved Me.” As a

singer and songwriter, do you find sad songs more interesting than happy

ones?

Hmmm… Well, you know, yeah. I guess.

It’s not essential. I don’t believe at this point that tragedy is

essential, but it’s certainly a part of the human condition. It’s

something that we turn to music to help us to sort out. But, I think it’s

often a harder thing to put across. The feeling of bliss or

(laughs) all of the wide gamut of

emotions. I think music, for me, was often something that I turned to for

a solitary fix. For support. Endurance. For sure. As a writer, I feel

like it’s been a challenge to overcome that; to not identify with tragedy

and melancholia alone. There’s so many different colors outside the

window. They’re all there for the taking. Interesting, though [for the

songs chosen on the album], I think that as detached and Reaganized as

the country and the world was, it was a depressing time [in the 80s] as

well. I think all the bright colors and the day-glo and everything

becoming plastic that was shoved in your face in the 80s was sort of

masking a much more quiet state of crisis. I think this music is probably

the document of that.

I’ve

written books on Tom Waits and Tori Amos...

Are they working together?

(laughs)

When I talk to songwriters I just like to throw their names out and see

what you think of them…

Well, Tori Amos, I’ve only seen her

perform live on television. (laughs)

I’m by no means an aficionado, but she’s

quite electric as a performer. Tom Waits, come to think of it I’ve never

seen him live other than a few televised performances and films, but I

love his records and his records I do know quite well. Interesting. Both

of those that you have sited are very theatrical. Conscious of offering a

certain kind of angle.

You don’t have to compare and contrast them…

Oh, yeah, it’s not my choice.

(laughs) It’s just my brain working. It

kind of also smells like burning toast in the room when I’m doing it.

Yeah, I mean, Waits is a big influence. I hear the influence of Tom Waits

in so much alternative music that you wouldn’t even think of. Eels, for

instance, you know? Largely influenced by Waits. I think probably some

of Aimee Mann’s albums are influenced, in terms of expression. Patrick

Warren, I would guess he must be influenced in some way. The cool thing

about Waits is that he really sort of just took a hard left turn. Like a

bat-turn. Just went (imitates screeching tires)

into a different direction. I think

probably that excited me more than anything when I first heard

Raindogs. It’s one of the things I still

think about. How do we want to deal with these drums? Do you want a good

drum sound or do you want to have some fun with it? Let’s really think

about it and a lot of that can be accredited to a record like

Raindogs.

In the end, how would you like people to look over your

career and your music?

Interesting… I guess I would choose to offer up a body of

work that can be pondered for a long time. Something to chew on that will

last. Just as you’ve gotten to the end of your Slim-Jim it’s grown

another mile. (laughs) A never-ending Slim-Jim. The most jerky

of jerkies.

Are there any misconceptions you'd like to clear up?

Any misconceptions? Hmm… I hope not. Not that I know of.

But it’s early in the day.