It was arguably the one of the most storied murders

in New York history, but the legend of the killing of Kitty Genovese is

also one of the most misunderstood. This tragic story is famous as much

or more so for the misinformation that has long been spread about the

situation than it is for the horrific murder itself.

Even if you do not recognize Genovese's name,

chances are you have heard the story. It is a sad and horrific tale

which has resonated for over half a century since it was reported in an

extremely evocative, if rather factually inaccurate article in The

New York Times, two weeks after the murder.

The accepted story pretty much goes like this: One

night, a bartender named Kitty Genovese was walking from her car to her

apartment when she was suddenly attacked on the street by a stranger

brandishing a knife. As Genovese struggled and screamed for her life

outside her apartment building, 38 of her neighbors looked out the

window and watched the crime. One man yelled out the window, scaring

the attacker off for a while, but no one went down to help Genovese, nor

did anyone call the police. Eventually, a half hour later, realizing

that no one was helping the woman, who was badly injured and desperately

trying to get back home, the killer returned and finished the job,

raping and killing Genovese.

It was a terrible, tragic story. In an America

still reeling from the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Kitty Genovese

became a symbol of "urban apathy" – proof that we are all alone out

there. Since then, the story has become a staple of pop culture, a

sermon from the mount on the evil of city life, cynical proof that most

people really only care about themselves in this world.

The problem is that the story was not exactly true.

No one knows exactly where the journalist came up with the figure of 38

people watching the murder. Yes, 38 people did testify with the police

about the fateful night, but most of them saw nothing. Some heard a

scream or fighting. A few claimed they saw a tiny bit of the attack.

Some claim that they called the police and were told that the police

were aware of the attack and on their way. The story claimed that

Genovese was attacked three times, but in reality it was twice, the

second fatal time in a section of the building that was very remote.

Also, despite the fact that the story insisted no one went to her,

Genovese's next door neighbor and friend did indeed go down, at her own

personal peril, and held and talked to Genovese as she died.

Some people may think that those are just little

facts, they don't mean anything. However, they meant everything to the

neighborhood, and more vitally to Genovese's family. Particularly her

younger brother Bill. Bill, who went on to be badly injured in Vietnam,

has never given up on his strong need to figure out what really happened

to his sister. This led Bill Genovese to meet filmmaker and

screenwriter James Solomon. The pair decided to get together to find

out the truth of not only Kitty Genovese's death, but also her life.

This 11-year quest led to the stunning documentary The Witness,

in which Solomon and a small film crew followed Bill Genovese as he got

past the lies and tried to come to a better understanding of the sister

he missed so badly, and of the night over 50 years ago in which she was

ripped violently away from him.

A few days before the New York premiere of The

Witness, we sat down with director Solomon to learn about the long

and winding road which led towards truth and healing and finally getting

a better understanding of the life and death of Kitty Genovese.

How

did you first learn about the Kitty Genovese story?

How

did you first learn about the Kitty Genovese story?

I'm a New Yorker. I grew up in New York City. For

most New Yorkers, it is as seminal a crime as there is, in the last 100

years in New York City. Everyone will know about it. I became most

interested [when] a literary agent named Andrew Browner had gotten

The 38 Witnesses reprinted. He had sent it to me when it was

getting reprinted – this was in 1999 – and I thought it would be the

basis for an interesting script. I'm a screenwriter. That's my

profession. I'm typically drawn to iconic stories we think we know.

Right. I don't know

if you'll remember, but the first time I heard of the Genovese story was

through a 1970s TV movie based on it called

Death Scream.

Right. I hadn't seen that. I remember that was one

of those incredible... it had sort of an all-star cast. Lots of great

actors. But I'm always drawn to these iconic stories. And then the

story behind the story. The last movie I did was about the Lincoln

assassination that Robert Redford directed called The Conspirator.

Before that I did a TV series called The Bronx is Burning about

New York in the 1970s. It starred John Turturro and Oliver

Platt. So, I'm drawn to these stories. Kitty Genovese being such an

iconic story felt particularly interesting. There are so many mysteries

of what happened that night in the apartments. How that story came to

be. Who is Kitty Genovese? Because she's only known for the last 32

minutes of her life. Who was this person Winston Moseley, who murdered

her? There are multiple mysteries and that was of great interest to

me. I thought it would make for an interesting screenplay.

How did you meet Bill

Genovese?

I sold a pitch to HBO in collaboration with two

others, Joe Berlinger and Alfred Uhry. It was at that time that I met

Bill Genovese. As research, I went up to meet with Bill where he

lives. The first thing that happens when you meet Bill Genovese is

you're immediately struck by how Kitty suddenly comes to life. She's

only known for the way that she died, but Bill was so close to her and

loved her so much that suddenly you begin to get a sense of Kitty. You

get a sense of a person that you really wish you'd known through Bill.

The other thing, Jay, that was really striking to me was just how deeply

impacted Bill was, not just by the loss of his sister, but the way she

reportedly died. That story, Bill said to me at the time, "I felt like

I needed to prove not only that I would have been someone who would have

opened the window that night, but would have gone down into the

street."

Nothing came of that HBO project. However in 2004

The New York Times actually revisited its own story and

questioned whether it was accurate. Having known how much Bill was

deeply affected by the story of that happened to his sister and how it

changed the course of his life, I reached out to him, to get a sense of

his perception and his thoughts. He expressed an interest and desire to

find out for himself what actually had happened. Also, in that article

it referenced Kitty's life and quoted her former roommate, who was

actually her lover. Bill didn't know a lot about her life in New York.

The combination of him wanting to find out what happened that night and

also what his sister's life was like in New York propelled him to want

to go off to investigate. He allowed me to accompany him. I realized –

I actually realized this in 1999, but I'm a screenwriter, so I was

writing a screenplay – but I realized that the best way of telling what

happened that night and who Kitty Genovese was, was through the people

who were closest with her.

Obviously

Bill was Kitty’s brother so he was connected, and yet he seemed much

more obsessive about Kitty’s death than any of the other siblings, who

mostly were trying to move on with their lives. Were you surprised

about how much effort he put into understanding a crime that happened so

long ago?

Obviously

Bill was Kitty’s brother so he was connected, and yet he seemed much

more obsessive about Kitty’s death than any of the other siblings, who

mostly were trying to move on with their lives. Were you surprised

about how much effort he put into understanding a crime that happened so

long ago?

I suppose the answer to that is yes, and no. No

from the standpoint of there were so many unanswered questions and

Bill's life had been so deeply affected by a story that had serious

flaws. It stands to reason to my mind that he'd want to find out

himself what actually happened, if he could do so. Keep in mind, Bill

was a scout in Vietnam. His job was a field intelligence scout. His

wife, early when I met her, possibly in 1999 he may have told me this,

but certainly in 2004 his wife described him as "always the scout."

That's Bill. In my mind, he's the ultimate truth seeker. He's

determined to find the truth wherever it leads him.

So if you have a sense of Bill, and that's part of

what he [does]. He explores. You get a sense of Kitty through Bill.

When you understand Bill's questioning, and his needing to find the

truth, seeking answers, you get a glimpse at who Kitty must have been.

Somehow, she answered his questions, she fed his questions, she

encouraged his questions. He said to me early on he wanted to do in a

way for others what Kitty had done for him: to give them voice. What

sets this film apart from any other – and for 50 years people have been

portraying in various ways the murder of Kitty Genovese, most recently

Girls and Law & Order: Special Victims Unit – but for 50

years no one has heard from the people who actually were most impacted

by her life and death. This is as inside a story of Kitty Genovese as

there has ever been, or ever will be. It's all because of Bill.

The original

New York Times

story portrayed Kitty’s murder in a way that it has become almost

shorthand for a certain idea – urban apathy; we are all alone out

there. Why do you feel that people became so entranced by the sad story

of her killing?

The original story is "For more than a half-hour 38

watched..." 38 watched. Let me look at the actual story. "For more

than a half-hour, 38 respectable law-abiding citizens in Queens watched

a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew

Gardens, and none called the police." Now, that story is so horrific it

creates a feeling of theater. A theatrical event. A staged killing

watched by an audience. That's what the story portrayed. Again it's

only conjecture, but if you go back in time in March of 1964, four and a

half months after Kennedy was assassinated, the country was exploring

questions of "Who are we?" This story spoke to that question. It was

a morality play. The crime rates in the cities around the country were

rising. Kennedy had been assassinated. There was a perception that

there was some kind of moral decay in the country. This story served as

a parable that reinforced this notion. It also spoke to a general

question. It spoke to everybody's fear of how alone are we? Are we

really on our own? What do we owe each other? Ultimate questions.

The problem with it is that the story simply wasn't

true. The narrative was flawed. Why it resonates, it resonated then

and it still resonates now, there is an expression that journalists

have: "Some stories are too good to check." This was one of those.

Now, had the story been accurately reported, as [writer and historian]

Jim Rasenberger says in the film, it would have been a three or four day

story. It was not going to be a big story.

Right, in a strange

way the

Times story, even though it was flawed, was the thing that made the

Genovese story resonate for all these years later. If the Times

had not pushed the idea of urban apathy, do you think anyone would

remember the death of Kitty Genovese other than her family and friends?

Correct, but also keep in mind one of the effects

was Kitty's life got erased as a result of that story. Of course she

would only be known to the public through her death, because she was not

a famous figure, so we would not know her name 50 years later if the

Times hadn't reported it as such. But, within the family, the

horror and tragedy was so profound and so great that even within Bill's

own family, within Kitty's own family, Kitty's life was erased. It was

easier for the family to cope with the loss by not talking. Cope with

the tragedy of her death by not speaking of her life. A woman who was

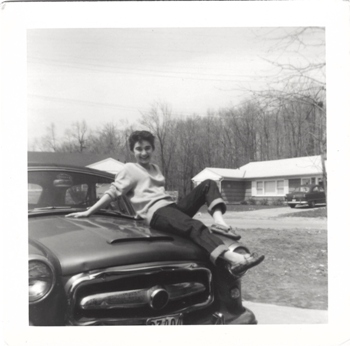

28 years old. She was almost... Kitty was like a millennial living in

1964. Drove a red Fiat convertible. Day manager at a bar. Picked up

her girlfriend in a bar in Greenwich Village. Fun dancer. Funny.

Really smart. There were lots of stories that a family presumably would

share, but they shared none, because [the pall of] her death was so

great. So, yes, you're right, in some respects, her name is famous and

stayed for 50 years, [but] within Kitty's own family her life actually

was erased as result of the tragedy.

How

difficult was it to track down living witnesses after 50 years? How

involved were you with tracking down some of the witnesses, or did you

allow Bill to do all the detective work?

How

difficult was it to track down living witnesses after 50 years? How

involved were you with tracking down some of the witnesses, or did you

allow Bill to do all the detective work?

The way it worked was, we identified in conversation

what it was that Bill was seeking. There were four mysteries,

essentially. Four or five mysteries that were of interest to Bill. He

wanted to find out what happened that night. He wanted to find out how

the story of his sister's murder came to be. He wanted to find out what

his sister's life was like in New York. He wished to find out who the

person was [who killed] his sister. Just to be clear, the guy was in

jail, but he wanted to find out what kind of person was Winston Moseley,

who murdered his sister. He cast an extremely wide net. He and I

talked about all the various people. He wrote down as many names as he

could gather. Then the process of trying to find if they were still

alive or not. We helped, so far as we could be helpful, to him, in

trying to locate the people that he wanted to speak to. If I wrote to

someone and invoked Bill, I sent him the letter before I sent it. If he

had questions, he was meeting somebody, he would write his questions.

He might send me the questions. I would send him some questions. Then

he would ask the questions he wanted to ask.

Over 11 years, a very intimate and close

collaboration develops between a filmmaker and a subject of a film. But

it was driven by Bill's need and objectives from beginning to end. We

get a sense that Bill is a very strong figure and has a clear sense of

what it is that he wants. But he's also, as you can see in every

interview and conversation he has, he's very open. So it becomes a

dialogue. I also should mention that in the course of making a film

about a brother who lost a sister, my own brother, John, got sick and

died.

I'm very sorry to

hear that...

So what started as an abstract understanding of

sibling loss for me became far less so. I had a much deeper

understanding of what Bill's loss must have been like. So on that

level, it was a real profound connection between the subject and the

filmmaker.

Bill's loss was also

probably compounded by his terrible wounding in Vietnam. He suggested

that he went into the war almost as a specific reaction to the apathy he

read about in the story of people not helping his sister. I know it's a

real leap, but do you think that the tone of the story is in some way

almost responsible for contributing to his becoming disabled?

That's a really perfect question that I have thought

often about. As you know, in life it's impossible to remove a moment

and imagine [what life would be without it]. I mean, you can imagine

it. In my personal opinion, yes. I believe, from the moment that I've

met Bill and the conversations that I've had with Bill, that not just

the loss of his sister, but also the story of how his sister died,

propelled Bill to enlist in the Marines. In a sense to prove that he

wasn't like one of the 38 witnesses. To prove, as he said to me, "Not

only would I have opened the window, but I would have gone down in the

street." Yes, in my opinion, had that story not come out as it came

out, as 38 watched, I don't believe Bill would have been motivated to

enlist in the Marines to go to Vietnam less that two years after his

sister's murder. But I have no idea, and that's critical. Who knows?

Jay, hypothetically, if his sister had just died

tragically and there wasn't the accompanying story, would someone's

grief and anger propel them to do something? Would wanting to get out

of the house? To get away? If nothing happened to his sister, would

John Kennedy's call to action – "Ask not what your country can do for

you..." – would that have propelled him? We don't know. We never

know. But I do think there was a direct correlation between the

reporting of his sister's murder and his decision to go to Vietnam.

It's the way he's lived his life. It didn't just stop with going to

Vietnam. He's always needed to prove that he wasn't like one of the

witnesses. He's always been a stand-upper, not a bystander. That's an

expression he uses.

Speaking

of things we'll never quite know, some of the witnesses that you were

able to find alive deny the allegations of the original story – one

woman insisted she called the police and was told they were already

aware of the attack and had been called several times; another woman

says she was with Kitty as she died.

Speaking

of things we'll never quite know, some of the witnesses that you were

able to find alive deny the allegations of the original story – one

woman insisted she called the police and was told they were already

aware of the attack and had been called several times; another woman

says she was with Kitty as she died.

Yes, that was Sophia Farrar. She had two children

and she and her husband lived next door. They just happened to live

next door to each other, but because she was a few years older than

Kitty and a mother, she had a particular affinity for Kitty. She was a

homemaker, so she was home a lot and she would talk to Kitty. They

became very close.

Obviously it has been

decades and no one will ever be able to prove anything, but did you tend

to believe these stories, or think that they were ways of dealing with

guilt, perhaps even false memories, after all this time?

Well, let's start with Sophia Farrar. There was a

newspaper at that time called The Long Island Press. Sophia

Farrar's name appears in those accounts in the first days as having been

there, at the scene. And having been there when Kitty died. She

testified in trial as having been there when Kitty died. So her story

is corroborated, either by her own statements [at the time] or

testimony. It's just somehow, somehow, over the course of a matter of

weeks, she gets dropped from the narrative. And the narrative becomes

no one helped. It strains credulity to understand how did her part of

the narrative get dropped? And this is the saddest, most tragic part of

it – for a half century Bill's family, particularly his parents, did not

know that Kitty died in the arms of a friend. That's astounding. And

so tragic. But she didn't make that up.

Now as to your point about... the film is very much

about false narratives. The stories we tell ourselves, either in the

middle of the night or across 50 years. Those stories that we tell

ourselves, whether they are real or they are imagined, are just as

important in shaping our lives. Steven Moseley [the son of the killer,

who is now a reverend] has told himself a story for many years about who

the Genovese family is. [In the interview, it comes out that he thought

they were related to the famous Genovese crime family.] That has helped

him, to some extent. And also what motivated his father. Those

narratives have helped him to live with the pain of a father who was a

budding serial murderer.

Were you surprised

when Winston Moseley wrote Bill and to this day was still proclaiming

his innocence?

His story changed. I don't know what Winston

Moseley actually believes. Winston Moseley, by the way, you should

know, died. He died at the end of March. The obituary was in The

New York Times. You can look at it. It was on April 4th. After

serving nearly 52 years in prison. Bill Genovese has a beautiful letter

that appears that he wrote to the Times, so if you wrote "William

Genovese, letter to the editor" you'll see a letter that he wrote that

was published in the Times after he died. Moseley's story

changed. I do not know. None of us knows what he really believed. But

it was a six page, single spaced letter, in detail. One can only assume

that he actually believed the narrative. What his psychosis and how

delusional this tale [is] refers to him.

But that's different. In my mind, that borders on

psychopathology. That's different than a story of somebody who thinks

they called the police and may not have. Or somebody who thinks that

the victim's family is the crime family. There are all sorts of stories

woven through the film. The other thing is, despite this flawed

narrative... you write about pop culture, right?... this flawed

narrative gives it staying power. Four weeks ago, Girls did an

episode largely based on the iconic story of Kitty Genovese. The famous

story. A month before that, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit

did its Kitty Genovese story. That's a show that's ripped from the

headlines. That headline is 52 years old. But somehow this story comes

back over and over and over again. It just holds the public's

imagination.

One of the most

interesting parts of the movie to me was in the middle when Bill

determined to learn more about his sister. They were close, but he was

16 when she died, and only six when they stopped living together. There

were a lot of things in her life that he just had no clue about. As you

were experiencing learning about her with him, what seemed to be most

fascinating to him about his sister that he learned through the

investigation?

Yeah. That's a good question. (Long pause.)

I'm just thinking about it. I think there are moments. Sometimes it's

pieces that come together. I think the moment where he and Mary Ann [Zielonko,

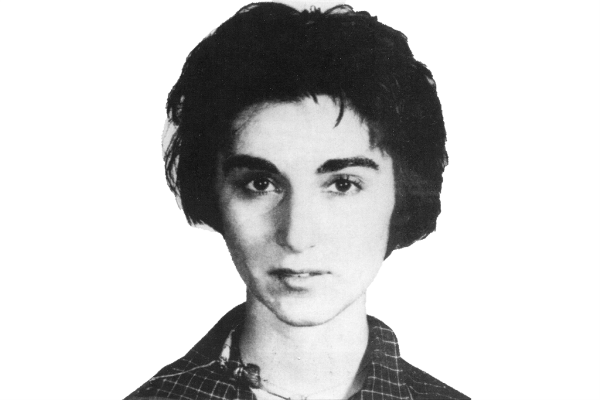

Kitty's former roommate and lover] are speaking of Andrew. I think

that's a very poignant moment. Finding out that the portrait of his

picture (most widely used in news stories) was actually a mug shot.

Putting that together. It's not as if the whole film hangs on it, and

not to talk about it too much, but I think that's a realization, in a

way. You look at a picture in one way for a long, long time, and then

you see it anew.

Clearly, he knew before he began, because it had

been reported in the paper, about Kitty's sexuality, but to the extent

to which he learned about her life apart [from him...] He knew Mary

Ann. Mary Ann would come to visit. But he didn't really know the

extent of their relationship, or just how deeply Mary Ann still felt the

loss. There's a very poignant moment. It's on audio, so it may not

resonate quite as much as it would if you were seeing two people

talking, but she says, "I only wish I'd known. I could have done

something." He says, "Yeah, I totally understand." That's a very

poignant moment.

There's that one reveal... it's interesting. It's a

good question, and I'm trying to think. One particular reveal about

her.... He spoke to people who weren't necessarily in the film, who

also filled in pieces of her life. One of them was a friend named June

Murley, an old friend. Having a sense of June's own awareness of

Kitty's sexuality, when Bill had so little. Particularly when you're a

young boy, growing up, and you look up to someone so much, you see them

a particular way.

I think it was very painful for him not to be able

to speak to Rocco, his sister's former husband. [Bill] had a real

memory of him and really liked him, was really fond of him. I think he

would have felt that Rocco would have filled in some gaps. Also, it

would have just been nice [to see him again]. I will say in general,

the part that he enjoyed the most was talking to people who knew Kitty.

You could tell, like

with the guys at the bar. He seemed to really enjoy hearing about that

aspect of her life.

Yeah, one of them, Victor Horan, told Bill that

Kitty was actually supposed to stay in the bar. She was supposed to

sleep on a sofa above the bar that night. It was kind of an arrangement

where she was going to be opening the bar the next morning at 8 a.m.

She'd gone out to a customer's house and had dinner with the customer –

two people. Afterwards, she'd gone back to the bar to pick up her car

at 2 o'clock in the morning. The invitation was there for her to stay

the night. She didn't take it. Like what we were talking about a

little while ago; choices, the things that happen that could have

changed the trajectory, really.

Do you feel that the

recreation of Kitty’s final night that was filmed helped Bill come to

terms with what happened?

I think that Bill had done everything you could

possibly do to learn as much about who his sister was and what happened

that night. But there was a gap, and that gap, I think, was an

experiential gap. It's one thing to gather information, which he did

relentlessly over ten years. To go to the apartments and to check out

sight lines. To review every piece of information, document, that he

could possibly get his hands on. But, always lingering in his mind, as

it would be in anyone's mind, [there was] a question of what it was

like. This is important, Austin Street, where Kitty was murdered, is

exactly as it was 52 years ago, except for the signage. It's as if a

standing set. He, I believe, thought he was going to do more of an

empirical check out of sightlines here. I don't think he understood. I

did. I had a sense this would be the case for him, but I don't think he

quite understood how immersive and how emotional it would be. I don't

know if you have talked to Bill, but...

No, I haven't...

... we had very strict guidelines as to how we were

doing this. We were not testing the neighborhood. We were not trying

to trying to do a stunt. We cleared this with the mayor's office weeks

and weeks in advance. We went to the local police precinct. We had a

police car on location. We alerted the neighborhood. We were a

physical presence in the neighborhood. Jay, we'd been filming there for

ten years. Kew Gardens was stigmatized. A lot of the residents of that

neighborhood were angry at the way that the press had portrayed their

neighborhood. But, because it was Bill, Kitty's brother, there was a

different relationship to him. From the very beginning, from the get

go. Bill had been in so many of these resident's apartments, so when

he's recreating his sister's final moments, he's a presence in that

neighborhood already. And we were a presence, as a crew. It wasn't

like we just showed up one night on the first day of shooting and did

it. It was the end of a ten-year journey.

There are two things I just want to make sure that

is clear. One is the reason this film is as inside this story as has

ever been, or will ever be is because of Bill. People felt they owed it

to Kitty. Many felt they owed it to Kitty to talk and because Bill is

as close to Kitty's surrogate as there is, they were willing to open up

to him. But he also has unique qualities. He has been a double amputee

since he was 19. He is, by virtue of that, accustomed to people feeling

uncomfortable when they meet him, and he puts them at ease. Secondly,

he embodies trauma. He understands it. People know that. They sense

that in Bill. So they open up to him.

Keep in mind this is not the selfie generation.

These people did not grow up on camera. They are talking about things

they have held inside for 50 years. In public, let alone on camera. It

is only because of Bill. They do that because he made them feel

comfortable. And our little intimate crew of few people who have been

working with him for ten years, we became sort of a family. That's the

dynamic that had to happen. That's why it took so long. We were very

low [profile]. We didn't advertise the fact that we were making film.

We were not trying to get press. We just let Bill do it at his own pace

and time. That's how we approached the film. I think the result is a

function of that approach.

Email us Let us know what you think.