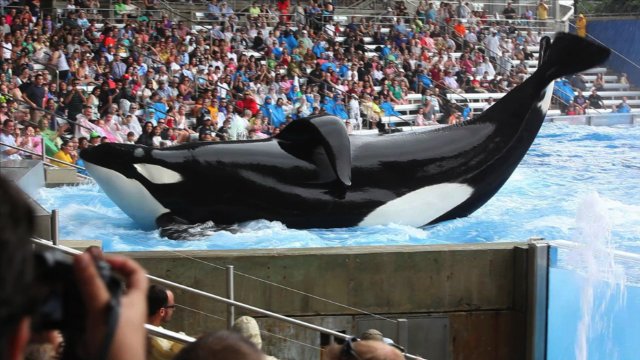

When SeaWorld trainer/performer Dawn Brancheau was killed by Tilikum

ó an orca who was a star of the aquarium/entertainment complex ó the

dangers of holding this wild species in captivity was spotlighted.

Little did most of the public know that this wasnít the first time

this particular whale had killed. Nor did they knew how crazed the

whale had become after years of being penned in.

This was such an amazing discovery for filmmaker Gabriela

Cowperthwaite that she devoted her time and money to creating the

documentary Blackfish in order to answer just why and how the

40-year-old trainer died. (SeaWorld Entertainment claims the whale

targeted the trainer because she had worn her hair in a ponytail.)

The thought-provoking film asks what to do about marine parks like

SeaWorld that exploit cetaceans for human amusement and profit.

The documentary kicks off with Tilikumís 1983 capture off Icelandís

coast. The movie reveals how he has been harassed by fellow captive

whales and was left in dark tanks for hours ó incidents this

director suggests prompted his aggression. Cowperthwaite also

focuses on SeaWorld's stated belief that captive whales live longer,

a claim that the film argues is false.

An experienced TV documentarian, Cowperthwaite has directed, written

and produced for such outlets as ESPN, National Geographic, Animal

Planet, Discovery, and History Channel. Her work includes History

Channelís Shootout!, a series for which she and a cameraman

were embedded with 300 Marines at Twenty Nine Palms. Cowperthwaite

was also behind Disaster Tech, a documentary series about the

biggest natural disasters in world history.

This new documentary has been racking up positive notices, awards

and favorable response ó including many protests of the whole marine

mammal crisis ó while also stirring SeaWorldís ire. When the feature

was about to air, this exclusive interview was conducted in

Manhattan. Cowperthwaite since has seen a successful DVD/Blu-ray

release and finds the film shortlisted for the Best Feature

Documentary Oscar.

Why did you embark on this project?

Why did you embark on this project?

I came at it with a burning question. How did a top SeaWorld trainer

come to be killed by a killer whale? I didnít get it. I know they

donít kill us in the wild, so I couldnít imagine that happening.

[Dawn] was actively feeding this whale, Tilikum, before he killed

her. It speaks to that fact that I think coming into a project like

this without an opinion or argument is okay. You can come in with a

burning question and keep digging and digging and digging. That

ended up being my method. It ended up being so fruitful because all

the information I was discovering. It was from a place of ignorance

so I just kept feeding my brain.

I knew that when I made the film I needed it to be very fact-driven.

It needed to be a narrative that had credible people like the former

SeaWorld trainers [such as John Hargrove,] speaking about what went

on inside. I needed to reveal it to the audience and arm them with

information the same way that I was able to discover it.

Did you ever go diving one day and meet a whale?

No. I wasnít even fresh off a trip to SeaWorld. It wasnít anything

like that. It was what happened. Then Iíd read another article and

Iíd think: ďYou just told me she slipped and fell. Why are you now

telling me it was her ponytail? Werenít there cameras? Didnít I just

see this on the news?Ē

So I just dug, thatís it. I had a burning question. I needed it

answered whether it was for my own edification or for a documentary.

I knew I would keep looking until I found the answer. If I have this

many questions, the world will have this many questions. If I am so

shocked by the answers then the world will be so shocked.

Going from making a film in Denver to this, how and when did you

make the shift? Did you do anything with nature before?

[I did a piece with] National Geographic about human phobias.

It would seem like Iím this naturalist.

I guess youíll never take your kids to SeaWorld, will you?

I guess youíll never take your kids to SeaWorld, will you?

I canít. Once youíve seen it, you canít un-see it. Thatís the only

way I can describe my experience. Once you know what you know,

youíll canít look at those silly tricks and think thatís cute. You

think to yourself this speaks of mastery. This makes me

uncomfortable. This is so sad. Whereas three years ago I thought to

myself I always described it as a cringe factor.

This doesnít feel right, and yet itís not abhorrent enough to get

you to get up and leave if you donít know the truth. You think to

yourself this doesnít feel right, but it must be okay because

everybody is smiling.

Knowing the cruelty of humankind, itís not that hard to understand.

What would be an appropriate space for a cetacean? Are there

environments large enough to keep them without just setting them

loose ó which canít happen for those raised in captivity?

We do advocate for sea sanctuaries, which would be a cordoned off

cove with a net, because of course these captive animals canít be

tossed back into the ocean. They donít know how to hunt. They canít

chase their own food. Like Tilikum whose teeth are all messed up.

They could be released into these sea sanctuaries. It would be

better in terms of what kind of enclosure can emulate their natural

environment, but thatís a tough one when they can swim up to 100

miles a day. It doesnít mean they would do that. I would just be

guessing since this is not my area of expertise, but you have to

have a big enough space so they can feel like they can get away from

you.

How far are we from communicating with these creatures? I wonder

what will happen when we do?

How far are we from communicating with these creatures? I wonder

what will happen when we do?

Sometimes I think about that and itís so overwhelming to even

imagine what it would be like to communicate with an animal like

that. An animal that has been on this earth for that long and

theyíve emerged as an apex predator. Theyíre a predatorís predator.

They can take down great white sharks. They live in relatively

peaceful communities or pods. So even the transients and residents,

when theyíre forced into captivity together, they donít even speak

the same language so they donít get along. In the wild, those

animals, when they do migration patterns just pass each other by

peacefully. When you think about what they could teach us, itís

astounding.

It would be fascinating to learn the languages of these animals ó

like in that Steven Spielberg series.

You think of the range of vocals, the languages. They can isolate

languages based on the vocalization of a certain orca. So they can

figure out where that orcaís family is.

Are killer whales the most carnivorous ones? I assume they eat

tunas.

For the most part the residents are the tuna and salmon eaters, but

the transients go for dolphins, seals, and sea lions. Itís this

uncomfortable fact, that they eat dolphins, an animal we also love.

Thereís some things you learn about these apex predators that

wouldnít be suitable for SeaWorldís literature because theyíre

trying to create this image that this is a fuzzy, huggable animal

that you can then buy in a store on your way out.

Like a lion.

Or a teddy bear.

How long did this take to make?

It took two years.

Did you tell SeaWorld what you were using the footage for when you

asked them?

Did you tell SeaWorld what you were using the footage for when you

asked them?

SeaWorld knew very early on what I was doing. I called them and

sought out an interview for about six months and we went back and

forth as they were considering it. At that point I was sure they

were going to be a voice in the film ó they had to be I thought.

Dawn died in the park and I came from no animal activism; Iím just a

mother who took her kids to SeaWorld. So I thought this was safe

territory for them. However, the moment they realized that I had

been interviewing people who had worked at their parks and had

captured whales for them, they declined. Itís a minefield for them.

For 40 years theyíve successfully kept these truths under wraps.

Besides the two deaths, were there others that involved whales?

There were the two deaths, Kelty and Daniel, Dukes, Dawn, and Kito

that killed Alexis Martinez. So thatís four human deaths and over a

hundred documented injuries ó thatís just the documented ones. From

what Iíve heard from SeaWorld trainers there are thousands of

undocumented ones.

Where do you go after youíve had that job if youíre not going to be

a trainer? How did you persuade people to talk against SeaWorld? Was

it to avenge the deaths?

That was what spurred them to come out and start speaking in public

about it. They heard the spin that was coming out of SeaWorld after

[Dawnís] death. She slipped and fell, or it was her fault.

They started hearing that and said, ďNo, that couldnít be true.Ē

They worked with [Tilikum] and were there. I think, and this is

corroborated, the former SeaWorld trainers speak out because all of

them had a hard time. Most of them had a hard time leaving and

leaving their animals behind.

The former SeaWorld trainers bond with their animals. When theyíre

forced to leave, they are forced to leave an animal theyíre afraid

will never be taken care of. They basically didnít feel like leaving

without knowing that they were going to be doing something for the

whales and speaking out for the whales.

Did you expect the response this film has gotten? And where does

that lead to?

Did you expect the response this film has gotten? And where does

that lead to?

I didnít expect it. I always make the joke that documentary

filmmakers never expect their films to be seen on purpose. We always

imagine people will run across them on the television ó maybe ó but

you never actually expect people to pay for it. So I have been blown

away by the response. Itís the idea that you created this intact

document that can now get in the world and go do some work. That is

like a dream come true.

Documentaries give me so much to worry about, now I have to worry

about SeaWorld! Have you seen other similar documentaries such as

The Cove or movies like Free Willy as research? Do you

want to go further into this subject, or are you done with it?

I do love the doc medium, I have to say. This is my storytelling

home. I donít know what comes next. Sometimes you think to yourself

maybe another topic out there needs the kind of energy I put into

Blackfish. Then thereís the other side of me that says thereís a

momentum here and I donít want to leave until I knowÖ This 80-minute

document has an amazing surrogate. Whether itís a cause for me, [to

support] sea sanctuaries.

I havenít hitched my horse to any one cause out there, as much as

Iíve gathered information from all of them out there and said,

ďOkay, whatís resonating with me and all the people that have seen

Blackfish?Ē Itís the idea of these sea sanctuaries. Itís the

idea that you have to stop the captive breeding and put them in

sanctuaries.

Has anyone made the connection between your movie and

12 Years a Slave ó another film about captivity and slavery?

Oh yeah. Itís tricky because that is probably the fastest way to

turn off members of the general public, by saying anything about

animals being slaves. Because that word is so heavy and it really

speaks about human horrors and atrocities. It has offended a lot of

people that I have spoken with. ďHow can you liken what has happened

to us with 40 killer whales at SeaWorld?Ē Itís very tricky

territory.

Whatís next?

Iím percolating some things right now. Itís terrible documentary

karma to ever talk about anything youíre doing. It will vanish the

moment you think itís something, before youíve gotten into it.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.