Thirty years ago, Warren Zanes and his brother Dan

led a hip rock band called The Del Fuegos. The Boston-based band

released three albums on the cutting-edge Slash/WB label, gaining a

cult following, but never quite making the breakthrough that was

expected. Probably their career high was getting the coveted

opening slot on Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers' Southern Accents

tour.

Zanes, who had grown up listening to Petty's music,

felt like he had arrived. Not only was he being paid to travel the

country playing his music, but he had a backstage seat to see one of

his favorite bands on a daily basis. He even got to know the guy a

bit, making it even more of a thrill. This kind of exposure should

have rocketed the Del Fuegos to stardom, but it was not meant to

be. Warren and Dan had a complicated relationship and Zanes left

the band after the third album's sales were not up to expectations

and Slash dropped them.

Eventually Zanes swerved from making music to

returning to school, earning his Masters and becoming a teacher.

However, he never completely got over his music, and he started

mixing it in with his academic career. Eventually that led to Zanes

writing a book on Dusty Springfield. It was that book which

re-established Zanes' relationship with Petty. Petty read the book,

and reached out to Zanes. After they had been back in touch for a

bit, Petty suggested that Zanes write a book about him.

There was a catch though. Petty promised complete

cooperation in the writing of the book. He would answer any

question, no matter how personal or embarrassing. He would also

help Zanes to get access to all living members and former members of

the Heartbreakers, including guitarist (and co-writer) Mike

Campbell, keyboardist Benmont Tench, bassist Ron Blair and drummer

Stan Lynch, as well as collaborators, friends and family. However,

Petty did not want it to be an authorized biography. He wanted it

to be a warts and all project.

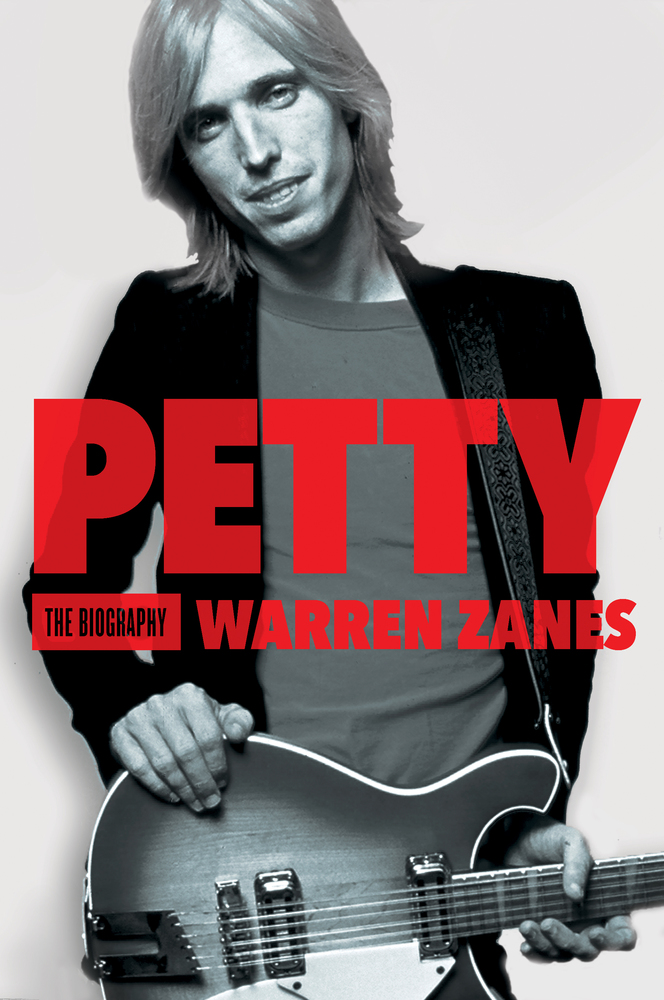

The fruits of that agreement has recently hit the

stores. Soon before the release of Petty: The Biography, I

caught up with Zanes to discuss the book, the experience and the man

who inspired it.

Almost 30 years

ago, you are a big fan of Tom Petty's who gets to open on his tour.

Fast forward and you are friends with the guy and writing his

biography. How surreal was that?

Almost 30 years

ago, you are a big fan of Tom Petty's who gets to open on his tour.

Fast forward and you are friends with the guy and writing his

biography. How surreal was that?

It's one of those surprising turns in life that you

don't plan and you're not fully prepared for. It was really

meaningful to me to come back into his life. I'd left the music

business and gone back to school. I was ensconced in universities

for twelve years, from starting my bachelors degree to finishing my

Ph D. I was really at a remove from the music business. He made

contact with me when he read a book that I had written in the 33

1/3 series. He got a copy and read it. I hadn't seen him in...

I think... more than 12 years. His management sent a message

saying, "Tom would like to have dinner with you next time you're in

Los Angeles." That started a whole new chapter in my professional

relationship with him. And I do call it a professional

relationship, [rather] than to call it a friendship, though it has

elements of that. But every time we're together, the reason we are

together is oriented around a project. That doesn't mean it's not a

relationship, but I'm going to call it a professional relationship.

(laughs)

Well, as you just

mentioned, you'd previously written a book on Dusty Springfield.

How did that come about?

That came about because while I had come into

graduate school and it was [working] on [my] Masters to the Ph D

program. I, like most graduate students, started doing more

teaching. As I was starting my professorial career, I brought more

and more music into the classroom. It just got me thinking about

music differently. Then, as I was finishing the Ph D, I got signed

to a record deal by the Dust Brothers, who had done Beck's Odelay

and The Beastie Boys' Paul's Boutique. I was thinking

about music more than I had in the previous decade. When I was

getting set to release this first solo record, my manager connected

me on a kind of blind date with Joe Pernice of the Pernice

Brothers. The first time I meet Joe Pernice and he says, "Hey, I'm

doing a book in this new series. Would you be interested in me

putting your name in the hat?" I said, absolutely. It gave me this

interesting opportunity to take some ideas that had been my

dissertation, but think them through in this more pop context, in

relation to this album that I had always loved, Dusty Springfield's

Dusty in Memphis. It was a total chance that I met Joe

Pernice and he connected me to this thing. I got to filter all of

this different thinking that had been up in my head. Then it's just

one notch crazier that Tom Petty gets a copy and reads it.

Tom came to you

about the book after reading the Springfield book. How did he find

out about it and why did he feel you'd be a good choice to write his

story?

I don't know how that happened. I don't know if my

publishers might have sent one to his management because we had a

previous connection. I don't really know. I didn't ask questions,

because I was probably too excited. (laughs) When we

finally had that dinner, he said "I read your book and I was

inspired to write a song that I want you to come back to my house

and hear." By that time I thought that I was involved in some kind

of overblown daydream. But it actually happened. What was

interesting also to me and for me was I'd just been a crazy kid in

the opening band. Now Tom Petty was thinking of me as a writer, at

a point that I was not yet thinking of myself as a writer. You can

do a few books before you really say, "You know what? I'm a

writer." I wasn't there yet, but Tom Petty was there. So he

started bringing me into projects as a writer.

You were

certainly in a rather unique position here. I've written two

unauthorized biographies – one on Tom Waits and one on Tori Amos –

and did not get much in the way of cooperation from either, in fact

Waits' camp sort of tried to sabotage it a bit. Petty gave you

pretty complete access, but insisted that it not be an official

biography. Why do you feel that was?

You were

certainly in a rather unique position here. I've written two

unauthorized biographies – one on Tom Waits and one on Tori Amos –

and did not get much in the way of cooperation from either, in fact

Waits' camp sort of tried to sabotage it a bit. Petty gave you

pretty complete access, but insisted that it not be an official

biography. Why do you feel that was?

He's got a laconic Southern presence, but his mind

is a very fast mind. He formulated the framework for this project

very quickly. He said, "Would you be interested?" I said yes. He

said, "This will be your book. It's not ghost-written. It's not

co-written. It's not authorized." He went on to say that he felt

that when he saw a book on the shelf that was authorized, he knew

that he couldn't trust it. It would be whitewashed. So, counter to

what the idea of authorized originally meant, he held it to become a

category [where] this is going to be the way that the artist would

like people to see it. That doesn't mean it's going to be the

truth. So he came up with the concept that gave me a higher level

of control than he had. He never refused me an interview. He never

refused a question. Every person that I wanted to make contact

with, he and his management team helped me make that contact.

You were in an

odd position knowing the man. When you were writing did you ever

wonder if certain parts may upset him too much?

It's a gritty account. I'm a fan of Tom Petty and

the Heartbreakers. I have been since I was 11 years old and I heard

their first album. I feel like they are America's rock and roll

band. I couldn't write an account any differently from the one I

wrote. The one I wrote, the author is a guy who holds Tom Petty in

very high esteem. So however gritty this was, I believe it's gritty

because lives are gritty. Lives are complicated. Show me the man

who hasn't made some choices that he later regrets. But in order to

give people like myself a better sense for the man who wrote the

songs, I had to go deep on the true story. That really was my

ambition, because the songs that I fell in love with could not have

been written by someone who led a tidy life. They wouldn't have

come from that person. They came from somebody who lived a

complicated life. So I needed to tell the story of a complicated

life so that people could listen to those songs at the next higher

level.

As you mention

often in the book, other than Stan Lynch, most of the band members

are pretty introverted, Petty included. Was it tough getting them

to open up?

It wasn't tough, because once one guy went there,

the others were willing to do it. It was very interesting because

everybody advanced as a group to the next level of opening up about

the Heartbreakers story. I felt very lucky at times to be the guy

capturing these accounts. I was not coming up against resistance.

I sometimes wonder if I'll ever have it this good again.

There are a lot

of details about Petty's early family life, particularly his

problems with his father Earl. How much do you feel that

relationship shaped who he became as an artist and as a man?

I think it affected him deeply. I'm a child of the

therapy generation. I'm a believer in much of [Sigmund] Freud's

thinking: What happens in childhood is integral to who we are. It's

going to inform our story every step of the way, I think. It

doesn't mean we don't change our relationship to that path, but I

don't think you can understand the man without understanding the

child. This is a child who was going through some shit that no

child should have to. It informed his later life deeply, I think.

To a certain

extent, Tom Petty is sometimes a little undervalued as a rocker –

He's always been respected, but he's not always mentioned in the

rock God firmament like Springsteen, or the Stones, or the Beatles,

or whatever. Why do you think that may be?

To a certain

extent, Tom Petty is sometimes a little undervalued as a rocker –

He's always been respected, but he's not always mentioned in the

rock God firmament like Springsteen, or the Stones, or the Beatles,

or whatever. Why do you think that may be?

I think because he is not a self-mythologizer. He

is not a self-promoter. His career would be bigger if he was

comfortable at doing that, but he's not. He is a guy who puts all

his focus on writing songs and making records and keeping the band

together so that they can continue to make records. But once they

are done, my impression of him has always been that he feels that if

the songs aren't making a strong enough case, then something is

wrong with the song. He shouldn't need to come behind them and do

back flips.

Early on, no one

seemed to know where to slot the Heartbreakers – were they New Wave,

were they punk, were they rock, were they alt? For example, one of

my favorite of their songs was "Louisiana Rain," which is almost

straight up country. Do you think about the band's diversity has

over the years made them so intriguing?

Yeah. They have such facility as a band. Listen to

The Live Anthology, which Petty said [was] the document to go

to if you really want to understand that band. If you listen to it,

[you] hear them doing "The Theme from Goldfinger," for

instance. You hear them do a Dave Clark Five song. Then you hear

them do some of their own extended live material that they've only

done live. They are many different bands without ever veering too

far from their identity. A big part of that is Petty's voice. He

can do a song like "Don't Come Around Here No More" and his voice is

such a strong central presence that even with some extreme

production changes, it still comes off as being a Tom Petty and the

Heartbreakers track. The band has the capacity to play in a wide

range of styles, while still being themselves. Petty has a capacity

to sing in a number of styles. But somehow their sound identity can

remain intact. I think that's helped them have a longer career.

Of course,

Damn the

Torpedoes was the album that exploded the group. Previously,

even though he had some success, he was still a struggling

musician. But between the breakup with Shelter Records and the

popularity of the album, nothing was ever the same for the group.

How overwhelming was that jump into fame for him and the band?

Of course,

Damn the

Torpedoes was the album that exploded the group. Previously,

even though he had some success, he was still a struggling

musician. But between the breakup with Shelter Records and the

popularity of the album, nothing was ever the same for the group.

How overwhelming was that jump into fame for him and the band?

I think it's overwhelming for anyone. We love rock

and roll for many reasons, but one of them is that it is a place

where we see people from the margins have big careers in the

mainstream. Our heads are pumped with notions of how powerful the

American dream is in our society, but the truth is we don't see it

embodied very frequently. We see it sometimes in sports, we see it

in entertainment, we definitely see it in rock and roll. It's Elvis

Presley. It's Buddy Holly. It's guys like Tom Petty. Did he have

to make a large adjustment, coming from lower on the class ladder to

becoming a rock and roll star? Most certainly. What he did was he

kept his head down and just kept working. If I were to give one

word attached to Tom Petty, I tell you he is a worker. I don't

think it's a codified work ethic, but he has maintained a pace in

his life. So the challenges of adapting to rock and roll stardom, I

don't think he was really so much dealing with them, because he was

just on the job. There were a lot of people standing around

him wondering where the next songs are. For decades.

In the late 80s,

Petty made

Full Moon Fever,

his first album without the band, although Mike, Ben and (late

bassist) Howie Epstein did work on the album a bit. They'd been

working together for years, how did the idea of a solo record sit

with the other band members?

Among other things, Petty is a tremendously skilled

bandleader. What his band wasn't seeing in that moment – and

understandably – was that Petty was making a choice in doing that

solo album that would ultimately benefit them. This was a guy who

needed to step away and breathe a little bit. He found a way to do

it. When he came back to the Heartbreakers, it gave them some

years. They are coming on 40 years and they are still together.

Some of these choices to make solo records came around at times when

he needed to do that in order to be able to come back and be the

strong bandleader that he needed to. From the band's perspective,

it was the first time with Full Moon Fever they'd seen him

doing that and I think it was very threatening. Also, the Jeff

Lynne records (Full Moon Fever and Into the Great Wide

Open) were done differently than they were accustomed to doing.

They were more constructionist records than the recordings of live

performances. It felt like: "What is Tom doing?" Petty's intuitive

and he's not asking for a lot of outside opinions, because he's

always believed in his own. So he did that thing, and there were

doubters on the sidelines, but the results certainly suggested that

Tom Petty made a pretty good choice in doing a solo record with Jeff

Lynne at that time.

You were actually

there for one of the earliest meetings with Bob Dylan and George

Harrison and Jeff Lynne that led to the creation of the supergroup

The Traveling Wilburys. What was it like to be a part of that

historic rock moment?

You were actually

there for one of the earliest meetings with Bob Dylan and George

Harrison and Jeff Lynne that led to the creation of the supergroup

The Traveling Wilburys. What was it like to be a part of that

historic rock moment?

Dylan wasn't there. It was George Harrison, Tom

Petty, Jeff Lynne and Mike Campbell. They were all sitting in Tom's

office at his house while the Petty family Christmas party was

unfolding in the next few rooms. The Pettys had given me a Beatles

magazine. I'm not a big go-get-the-autograph kind of guy, but this

felt like an unusual circumstance. (laughs) Just unusual

enough for me to go get the autograph. Jane Petty, that's Tom's

former wife, she kind of almost pushed me into this room. There

they are, playing music together. For me, I did not view it as

historic. I didn't know what it was. I knew there were some

legends in the room. And I knew that I felt tremendously

uncomfortable. So after I got my autograph, I got out of there

pretty quickly, because they were in their world and I rightly

didn't view myself as a member of that. So I left with my magazine,

which my sons will inherit. (laughs)

Petty had never

really discussed his heroin use before, even in the

Running Down a

Dream documentary. Why do you think it was important to him to

discuss that important but embarrassing addiction?

At one point he said to me, "There's no reason to do

anything but just tell the truth at this point in life." He did

have hesitation. He worried that even if there was one kid out

there who might romanticize drug use because of Tom Petty's story,

it wasn't worth telling that story. I said I believe that we're in

a time where there is more awareness about addiction. This can be

told in such a way that it's not going to be romanticized. I felt

strongly that could be done. So with his interest in telling the

whole truth, and us finding a way, I think he felt ready. I don't

have anybody writing my book, but I imagine it's hard to go through

this experience. That I am seeing eye to eye with him. We set out

to do what he wanted to do. I think we really arrived at an honest,

good book. I believe he sees that, but at the same time he is

having to live through the process of seeing new difficult

information about his life going public.

One of the

biggest things you got here is that you finally got Stan Lynch to

open up on his mysterious break with the band. Everyone has been

pretty hush-hush for years about that. I'm afraid I'm not quite

that far into the book yet, but how did that come about? Were you

surprised that Lynch finally opened up about that?

One of the

biggest things you got here is that you finally got Stan Lynch to

open up on his mysterious break with the band. Everyone has been

pretty hush-hush for years about that. I'm afraid I'm not quite

that far into the book yet, but how did that come about? Were you

surprised that Lynch finally opened up about that?

It's tough to say: Would Stan have done interviews

earlier if people had come in a more personal style? That's what

Stan says. He says it wasn't about not doing interviews, he just

said nobody came to my door like [I] did. But, he said no several

times before I went to him and said, "Stan, I just don't think I can

do this without your involvement. I'll come to your front door in

Florida if you just give me 20 minutes. If after 20 minutes you

want me to leave, I promise I will leave." That's what we did. I

flew down there for those 20 minutes and then it turned into eight

hours. I really needed his voice. Only people who have been in

bands can understand that it doesn't matter that 20 years have

passed. The feelings are still strong. I was only in a band myself

for five years. That was many years ago, but I still feel some of

the disappointment. I still feel a little bit of the anger at how

things got handled by my brother, who was the band leader. We

worked through a lot of it, but these things... it's just like

feelings from childhood. Feelings from the time that you're a young

man. They don't necessarily have an expiration date. A lot of

Stan's feelings had a strength to them. A lot of Tom's had a

strength to them. I can understand why. These guys went through a

lot together. They saw their lives flipped upside down by success.

Then they had to negotiate it. Negotiating how to handle success

was mostly on Petty's back. He had a group of his friends from his

hometown watching how he did it. And you know what? Several of

them were going to get resentful. I don't think there would be any

way around that. But, I needed Stan to voice some of that, in order

to give the experience of being in a long-term band and leaving it.

A real taste is in the pages.

Did you ever hear

what Tom thought of the final book?

Our arrangement was that he got to read it before

publication. When we set up the parameters here, he said, "I'm not

going to tell you what is in it and what is not in it. But I'm

going to ask for the opportunity to read it before publication and

respond to anything that I feel begs a response." That, too, he

stuck to. He never said "Don't put that in there and put this in

there." Never. But we sat down and went through the entire book

together. We did the first half over a two day period. We did the

second half over a four day period. He got to address what he

wanted to address. Then I found a way to sew his voice into the

existing narrative. It was, without a doubt, one of the more

intense, human experiences I've been through. I didn't come out of

any of this with less of an admiration for Tom Petty. If anything,

I came out with more of an admiration. He is a man of principle, a

man with a really defined set of values that organize his life.

He's a guy that I still look up to in many, many ways.

What is your

personal favorite Tom Petty album or song?

This is the truth, it shifts. It really depends.

That's a testament to how strong his catalogue is, from beginning to

end. I'll often be listening to the newest records. I listen to

Hypnotic Eye a lot. Songs like "All You Can Carry" and

"Forgotten Man," these are incredible tracks. I went through a

period when these were my favorites. But I was looking back at the

first record lately and listening to "The Wild One, Forever" and

"Mystery Man" and going, okay, today this is my favorite. It could

be Southern Accents. I went through a period where Let Me

Up (I've Had Enough) was my favorite, for however uneven he

thinks it is. He has a hard time listening to Echo. I know

people who say Echo is the best record. Or, I was just

talking to somebody yesterday [about] Long After Dark. Petty

turns up his nose at that one, and I think it's incredible. I'm

talking to Mike Gent from the Figgs, and Mike Gent did what Ryan

Adams did with the Taylor Swift record. He went and recorded the

entire Long After Dark in sequence, solo acoustic. (ed.

note: He recorded them under the name Gents Parlour.

Interestingly, Gent changed the album title to Long After Stan.)

Because he fell in love with that record. That's his favorite.

Man, his catalogue is so good, the effect is the same as The Beatles

catalogue. In some ways The Stones catalogue, but there are a few

things in the Stones catalogue that don't measure up. But The

Beatles, you can go anywhere and be satisfied. Petty you can go

anywhere and be satisfied.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.