It wasn’t a

dream. It really happened. People looked that way, dressed that way

and played that way. Yes, the uniforms were that tight… and, oy,

those colors. Dan Epstein tells us so in his awesome book, Big

Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in

the Swinging ‘70s.

A ride indeed, in

an AMC Gremlin over a road of potholes. Hang onto your seats. It’s

going to be a bumpy decade. Here, we talk with Dan about what it was

like stayin’ alive in the big leagues, gettin’ our turn at bat.

Major League

Baseball pretty much stayed the same during most of the twentieth

century, but in the 1970s, something happened.

It’s always been a conservative game, really. Even

now, to some degree, there is an element of conservatism to it. The

‘60s is when you really see how far apart baseball and pop culture

were. In the ‘70s, the bubble around the sport is pierced and you

start seeing players expressing themselves on the field.

Let’s start with

the obvious: those horrid new stadiums and the Astroturf.

The “concrete donuts” of the ‘70s were built to be

multipurpose stadiums. On one hand, it was an improvement over the

old stadiums, in a sense that there were no steel girders blocking

fans’ views, and the seats were wider and more comfortable. But

because of the way they were shaped, everybody was farther away from

the action. There wasn’t that sense of intimacy that you had at

Tiger Stadium or Fenway or Wrigley Field. Part of the multipurpose

function was the artificial turf [Astroturf]. It was easier than

pulling up the diamond and putting down the gridiron. It really

changed the way the game was played. The ball took much bigger and

faster hops. The teams that won on artificial turf did so by taking

advantage of that fact. If a line drive bounces correctly, it can be

an in-the-park home run.

Jim Bouton’s 1970

blockbuster book,

Ball Four, was

an expose of baseball players, both on and off the field. Fans ate

it up, but it did not make a lot of players happy.

Jim Bouton’s 1970

blockbuster book,

Ball Four, was

an expose of baseball players, both on and off the field. Fans ate

it up, but it did not make a lot of players happy.

Ball Four

was pretty raunchy for a sports book at the time. It was a baseball

book about players chasing groupies, and the way players talked to

each other in an unvarnished way. It presented these guys as guys,

not these white-knight American idols. Just your average, horny,

foul-mouthed athletes. The Astros actually burned a copy of it in

their dugout. Pete Rose yelled at [author Jim Bouton], “Fuck you,

Shakespeare.” It’s like Bouton breached the clubhouse code. Up to

that point, what went on among ballplayers on the road was pretty

much unknown to the public.

These were not

the days of millionaire ballplayers, like today.

In the days before free agency, most of the

ballplayers were living a pretty much middle-class existence at

best. A lot of them were working odd jobs in the off-season to make

ends meet.

The

counter-culture revolution in baseball seems to have first sparked

with the Oakland A’s.

The whole explosion of long hair and mustaches

started with the 1972 Oakland A’s. This all happened because Reggie

Jackson came into spring training with a full beard. The team

actually had rules about grooming, but Reggie being Reggie, said,

“Fuck that. I’m going to wear this beard.” [The management] offered

to pay the rest of the team to grow mustaches and beards to steal

Reggie’s thunder. But the players found that they were playing

better with the mustaches on. Baseball players are a very

superstitious breed. The A’s were playing better together with the

facial hair. It was also a bonding thing. In 1972, their opponents

in The World Series were the Cincinnati Reds, who had really

stringent player grooming parameters. The media played it up: The

Hairs vs. The Squares World Series. The message: you can look like a

hippie and still play world champion baseball. After that, a lot of

teams started relaxing their restrictions.

Relaxed indeed.

We’re talking about Afros, muttonchops, and porn ‘staches.

Relaxed indeed.

We’re talking about Afros, muttonchops, and porn ‘staches.

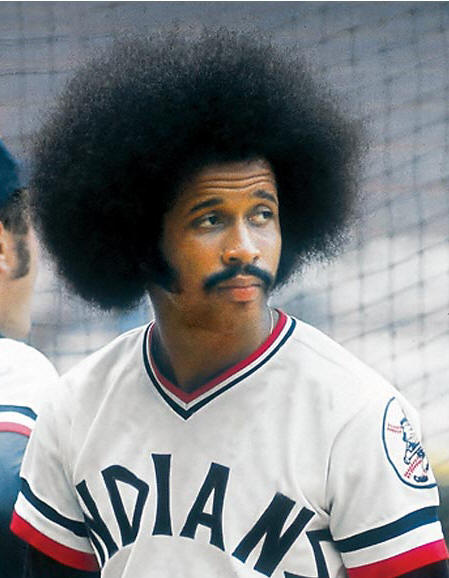

You can’t talk about ‘70s baseball hair without

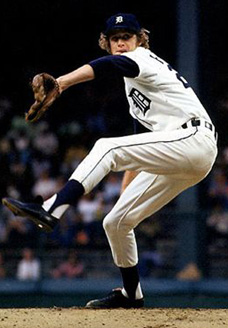

talking about Oscar Gamble. He’s on the cover of the book for good

reason. He had the largest Afro ever seen on a major-league player.

There were plans for him to do an Afro Sheen commercial. There were

a lot of white guys wearing essentially perms: Mike Schmidt, John

Montefusco, Randy Jones, Mark Fidrych of the Tigers. That was no

perm – that was actually his hair. Dock Ellis was spotted in the

Pirates’ bullpen wearing pink curlers in his hair. Joe Pepitone was

a special case. That was a wig. In the ‘60s, he was the first ball

player to bring his own hair dryer into the locker room. He bought

these special toupees, for on the field and off the field.

The uniforms of

the ‘70s had a special, uh, uniqueness.

That was such a colorful period for uniforms. The

Houston Astros had Tequila Sunrise stripes. You could make an

argument that that was the ugliest uniform ever worn. On the other

hand, you can make the argument that that was the most awesome

uniform ever worn. I have a soft spot for the Chicago Cubs pajamas.

They were baby blue with white pinstripes. It was a combination that

no one ever used before or after. They were really hideous,

especially with the elastic waistband. For three days in 1976, the

White Sox went out on the field wearing shorts. It never happened in

the majors before or since. It’s so badly scarred in White Sox fans’

minds that to this day a lot of them believe that they wore shorts

all season.

Stadium

promotions of the ‘70s had a special air of desperation about them.

Promotions in baseball stadiums [prior to the ‘70s]

were limited to Ladies’ Day or Family Day. [White Sox owner] Bill

Veeck was the first to try to pull in people with giveaways and

lotteries, anything that would get some press and get people into

the ballpark. It was really frowned upon by most of the other

owners. The ‘70s had some of the most successful seasons in terms of

attendance. But the NFL was becoming much more popular. The NBA

hadn’t yet elevated itself to the point that it would be in the

‘80s. Baseball was no longer the big sport in America. They were

being challenged by other sports. You had to give people some kind

of reason to show up.

Even if it meant

witnessing a streaker running naked across the field.

Well, you can’t talk about the ‘70s without talking

about streaking. It hit critical mass around 1974. That was the

famous Chicago White Sox opening day where it was 38 degrees but you

have all these streakers running across the field at Comiskey Park

between pitches and that got the crowd riled up. At any sporting

event in the mid-‘70s, chances are you were going to see a streaker

at some point. It went along with the whole ‘70s “do your own thing”

and the body beautiful and the throwing off of the conservative

shackles. And it was always good for a laugh.

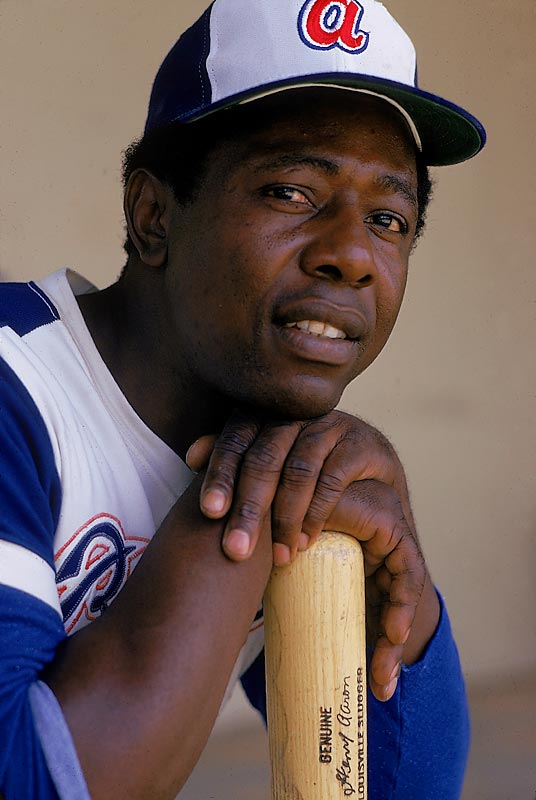

The Atlanta

Braves’ Hank Aaron, an African American, beat Babe Ruth’s home-run

record in the ‘70s, but many people were not enlightened enough to

accept it.

The Atlanta

Braves’ Hank Aaron, an African American, beat Babe Ruth’s home-run

record in the ‘70s, but many people were not enlightened enough to

accept it.

It looked like he was going to break the record in

1973, and that’s when he got the bulk of the hate mail. The notion

that a black man would be breaking Babe Ruth’s record, which stood

for about 40 years at that point, really didn’t sit too well. By

1974, it was obvious that he was going to do it and there was a lot

of anticipation.

Sports marketing

was in its awkward infancy in the ‘70s. It was not the

sophisticated, sleek machine it is today.

Nobody really knew what they were doing. Pete Rose

for instance: not a particularly attractive man, not a man I would

think people would look to for grooming tips, shilling for Aqua

Velva. There were oddball things like the “Johnny Bench Batter Up,”

which was a hitting aid for kids. It didn’t really work unless you

poured your own cement base for it. You had to go down to the

hardware store and buy a sack of cement.

There were also

teams recording pop songs and those records were getting airplay and

hitting The Top 40.

That goes back to the Sixties. The 1969 Cubs were

one of the first with a record called “Pennant Fever.” Several

members of the team sang about how they were going to go all the way

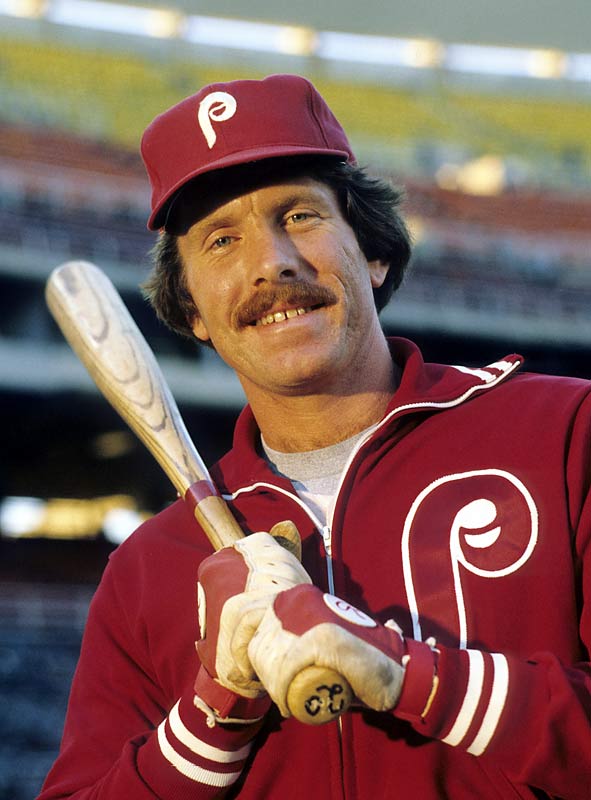

in ’69, which of course did not happen. The Phillies had “Phillies

Fever” in 1976, recorded by five players. That’s actually my

favorite one of the era. It’s sort of a disco song and it has

low-budget “Sound of Philadelphia” strings, which is very

appropriate for the period and the geographical location. And they

bring CB radio lingo in at one point: “The Phillies are gonna go all

the way, good buddy. 10-4.” It’s a terrible record, but I love it.

It seemed like

the end of the decade came with Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey

Park in 1979. It was one of the all-time great fiascos.

It seemed like

the end of the decade came with Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey

Park in 1979. It was one of the all-time great fiascos.

That was one of those promotions that we can all

agree that it got out of hand. But beyond that, opinions are widely

varied. A local DJ, Steve Dahl, really beat the drum for “Disco

Sucks.” The whole anti-disco movement really caught fire in the

mid-‘70s. Disco probably reached its cultural and artistic high

point around the time of Saturday Night Fever (1977). After

that, it really became “product.” The Top 40 was completely gutted

with disco music. The disco backlash manifested itself in the

anti-disco night at Comiskey Park. Not even Steve Dahl knew how

popular this event was going to be. I think they expected to draw

maybe an extra 20,000 at best, for a really awful White Sox team.

And this was a team that was putting on promotions all summer and

not really drawing people. But the place completely sold out.

You bring a disco record to the stadium to be

destroyed and you would get in for 98 cents. People are coming just

to party. Most are not even getting into the ballpark; they’re just

hanging out and smoking weed and getting wasted. So many people were

bringing in disco records that after a while, ushers stopped taking

them from people. People are so jazzed by [the record pile being

blown up] that they start running out onto the field. It just

destroyed the field. The second game of the double-header had to be

forfeited. In some ways, this is a black mark. It’s ‘70s baseball

promotions gone awry. At the same time, for a whole generation of

Chicago kids, this was one of the fondest touchstones. It was a

moment of anarchy and liberation. The meaning of disco demolition

will be debated until the end of time, but it was definitely a

pretty colorful way to end the ‘70s.

You mention in

your book that baseball looked very different in 1979 than it did in

1970.

Oh, yeah, and not just the grooming and the

uniforms. The designated hitter was introduced in 1973, and by 1976,

it’s in the World Series. Also, the players’ salaries [rose], when

the reserve clause was finally banished in 1976. They hold the very

first free agent re-entry draft. Suddenly, players are signing for a

million dollars over ten years, which now sounds like chump change,

but for baseball players then, this was huge. The whole salary

structure gets massively overhauled by the end of the ‘70s. This is

not just adjusting for inflation. This changes the way teams are

constructed. It drives “mom and pop shops” out of the business

entirely.

Was the thrill

gone by the ’80s?

It was for me. I checked out of my baseball

obsession around 1985 and didn’t come back until the Sosa/McGwire

home run chase in 1998. That whole period in between is just a blank

to me. The baseball strike in 1981 took a lot of the wind out of my

sails.

Ultimately, how

do you sum up the uniqueness of ‘70s baseball?

The ‘70s was this era where you can’t separate

baseball from what was happening in the country. That’s one of the

things I love about ‘70s baseball.

Double-play! Dan Epstein’s first book about ‘70s baseball,

Big Hair and Plastic Grass,

captured the pastime the way it used to be played back in the day

game, as well as capturing the zeitgeist of a nation in turmoil and

transition (two words: polyester). In the course of his research for

that book, Dan discovered the historic awesomeness of the 1976

season in particular. it seems the baseball happenings of that year

could fill more than a mere chapter.

The result: Stars &

Strikes, rounding home with a raw and righteous/outa

sighteous season of high drama (comedy too). We celebrate the

nation’s bicentennial while striking out Nixon and Viet Nam. Disco

was not yet called foul, a quirky young man who resembled Big Bird

took flight, and the major leagues went Major League. Not

surprisingly, that was also the year of the gorgeously cynical The

Bad News Bears. America, finally feeling its oats again,

quoted that flick: You can take your apology and your trophy and

shove it up your ass! Just wait until next year!

Here, our good buddy Dan gives us a big 10-4 on the book

(it’s a hit!) while he catches us on the flip-flop.

Dan, why 1976?

Culturally, 1976 really appeals to me because it’s such a

transitional year in music, politics, and in the sense that America

was kicking loose the last vestiges of the Nixon administration, all

the rage and the paranoia and that whole bummer of the early ‘70s.

[The attitude was:] “That’s all behind us! Let’s put on our boogie

shoes and paint some fire hydrants red, white and blue and really

enjoy!” There was such a sense of hopefulness and togetherness that

I had not seen in my lifetime in this country. It was a moment of

“we’re all in this together.”

Yet the actual Bicentennial itself was ultimately a bit of a

letdown, right?

It was so hyped. There was such a glut of Bicentennial souvenirs

manufactured. None of them became valuable and most of them were not

very attractive. There was a real interest from Americans, but at

the same time, it was so over the top and so oversaturated, with

immense, lavish, over-the-top celebrations. By the time July Fourth

actually showed up, I think people were ready to let it go.

What was the team to watch that season?

What was the team to watch that season?

The team to watch was the Cincinnati Reds. They had already won the

1975 World Series, with basically the same group of guys. It was the

most intimidating lineup in baseball at the time. It was pretty much

a foregone conclusion that they were going to come close if not

totally repeat their success. The Philadelphia Phillies were not in

post-season since 1950, but yet, in time for the Bicentennial, they

got it together. It really came together for them that year. The

Kansas City Royals made the playoffs for the first time in their

history. They were an expansion team in ’69.

The New York Yankees had not been to a World Series since 1964. They

had a lot of pretty dismal seasons, and George Steinbrenner came

back after being banished from baseball for two years, along with

Billy Martin. They were great right out of the gate. It’s

interesting that the Yankees became great at a time when the whole

country was ready to write off New York City. They become a huge

source of pride for the city. A comeback.

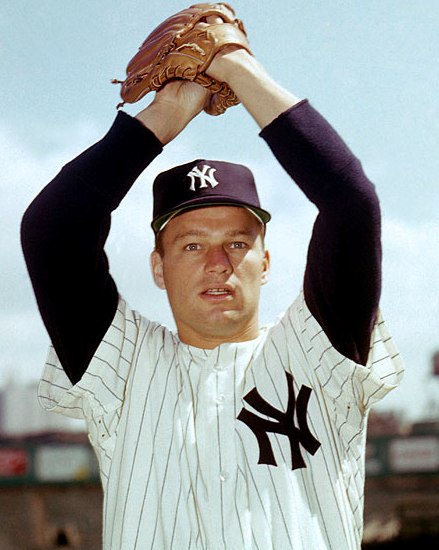

The breakout star of 1976 was Mark Fidrych, nicknamed “The Bird.”

His story sounds like fiction, except for the fact that it was all

true.

The Tigers were not entirely sure what to do with him. They knew he

was very good. From Opening Day until the middle of May, he only

gets into two games. Another pitcher gets sick, and he gets to be a

starting pitcher. It’s right out of a Hollywood script. He pitches

phenomenally well. Not only is he a great pitcher, he is very quirky

and charismatic. He is talking to the baseball, and he’s dropping to

the mound to smooth out the cleat marks that other pitchers have

left, shaking the hands of his infielders every time they make a

good play.

There is a pure joy that is radiating from him. That was a big part

of his appeal. It was a time of free agency and players demanding

more money and not being loyal to their team, and here is this guy

who looks like a 6’3” Little Leaguer. He’s just completely stoked to

be out there. He’s playing for the rookie minimum [salary]. By the

end of June, he is a national phenomenon. Yet he seems to be

unphased by it. He’s not cynical or super flamboyant. He’s not

boastful. He just loves to go out there and throw a ball. It

resonated very deeply with baseball fans and non-baseball fans

alike. He was like a rock star. 1976 was his lone full season. It

was this brief, beautiful moment, and then it was over. He didn’t

stick around the game. He just left and went back to Massachusetts

and bought himself a farm.

There is a pure joy that is radiating from him. That was a big part

of his appeal. It was a time of free agency and players demanding

more money and not being loyal to their team, and here is this guy

who looks like a 6’3” Little Leaguer. He’s just completely stoked to

be out there. He’s playing for the rookie minimum [salary]. By the

end of June, he is a national phenomenon. Yet he seems to be

unphased by it. He’s not cynical or super flamboyant. He’s not

boastful. He just loves to go out there and throw a ball. It

resonated very deeply with baseball fans and non-baseball fans

alike. He was like a rock star. 1976 was his lone full season. It

was this brief, beautiful moment, and then it was over. He didn’t

stick around the game. He just left and went back to Massachusetts

and bought himself a farm.

Team

owner Bill Veeck also continued to make waves as a colorful

character that year. How did he possibly top himself?

Veeck returned to Chicago at the end of ’75. He was a really beloved

character in Chicago. His return was a huge event. He was

gregarious, down to earth; he liked to sit in the stands and drink

with fans. He had an ashtray built into his wooden leg. This was not

your stereotypical, uptight, patrician team owner. When he bought

the White Sox, they were in a lot of trouble. They were a terrible

team and they were hemorrhaging money. They weren’t drawing anybody

to the park. Veeck realizes that he does not have a lot to work

with. So he comes up with all of these promotional ideas. This has

always been a big part of Bill Veeck’s game plan. He was a big one

for off-the-wall promotions, anything that would get some press

coverage.

He has beer-crate-stacking competitions, ethnic nights [his

ballplayers running out onto the field in sombreros for Mexican

Night], and giveaways. He was really the king of this stuff. He

designed a whole new uniform for the White Sox. They have collars.

He also designs Bermuda shorts. To this day, some fans believe that

the White Sox played an entire season or more in those shorts. They

were traumatized, like a false memory. In actuality, they only

played three games. The amazing thing is that the White Sox won two

of the three games that they played in shorts.

Pete Rose was another one to watch in ’76, as usual.

Pete Rose was another one to watch in ’76, as usual.

Pete Rose had a really good year in 1976. Pretty much every year in

the 70s, Pete Rose had a very good year. You can’t talk ‘70s

baseball without talking Pete Rose. The Reds just dominated the

Yankees in the World Series. Pete Rose was great at getting into

players’ heads.

What was the state of stadiums in ’76? A pretty sorry state, right?

1976 had an interesting mixture of ballparks. You still had the old

places like Tiger Stadium and Wrigley Field. Then you have the

concrete donuts that are covered in Astroturf, like Veterans Stadium

in Philadelphia and Royals Stadium in Kansas City. 1976 is the year

of the only rainout in Astrodome history! That’s one of my favorite

facts. There was terrible flash flooding in the area before a game.

Yankee Stadium comes back to life after two years of renovation.

They really change a lot of the character of it. San Francisco

nearly lost the Giants at the beginning of 1976. They were broke and

their owner was desperate to sell to anybody. The Giants had the

worst attendance in the National League. Part of the reason is that

Candlestick Park was a miserable location for a ballpark. They did

nothing to promote the games and nothing to encourage people to come

out. It also had a reputation for serving literally rotten food.

Ted Turner’s meteoric rise began that year too.

Ted Turner was a visionary in a way that nobody really understood at

the time. He was the owner of a UHF station in Atlanta that most of

the city couldn’t even pick up. These were the days before cable. He

has the idea of turning this UHF station into a satellite network

that could be beamed all over the country. He realizes that

broadcasting Braves games could be a big help with credibility. He

needed to keep his relationship with the Braves going in order to

expand his station.

The prevailing wisdom was not to televise too many games because you

want people to come out to the ballpark. Turner was doing just the

opposite. He had a much bigger goal in mind. Soon, there were Braves

fans all over the country. They were a terrible ball club, but

Turner made the stadium a happening place where people wanted to

come. What TBS eventually became changed baseball’s relationship

with television.

The biggest

change of the year is that players suddenly and finally got control

of their careers.

The reserve clause is revoked and now if players don’t sign a

contract with their team, they can play out their option and

negotiate with other teams and get paid whatever the market will

bear. The effect of this is mammoth. It will completely change the

way teams are built. It will completely change the economic

structure of the game. Everything we have today, from hyper-inflated

players’ salaries to the multi-billion-dollar cable deals, all come

from 1976. This is where it all starts.

How do you feel about this change?

I

don’t like what the game has become. I don’t like watching guys who

are multimillionaires playing while knowing that next year they will

not be on the same team. But if baseball is raking in the cash, then

players do deserve an equitable part of the pie. Up until 1976, they

weren’t getting that. I think that free agency was absolutely the

morally right path to go on, but it became a Frankenstein monster.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.