Copyright ©2014 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

April 5, 2014.

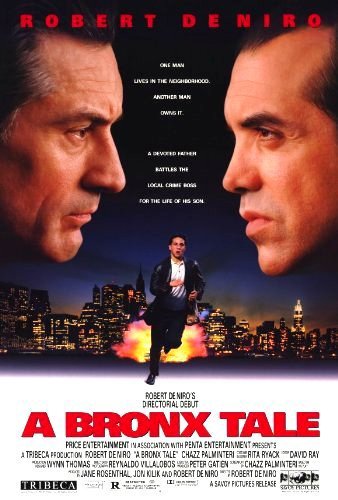

On February

26, 2014,

the First

Time Fest team held a special event in tandem with Tribeca

Enterprises in anticipation of the 20th anniversary of A

Bronx Tale, Oscar-winning actor Robert

De Niro's directorial debut. Since the concept of the

fest is to celebrate directors and their debut features, this film

screening served to hail a career benchmark for De Niro and

Chazz Palminteri,

its star and story creator.

Though De Niro has since done another film as director, 2006's The

Good Shepherd, he had a powerful personal connection to this story.

Though Taxi

Driver really made him a figure to reckon with,

several of his earlier films such as Mean

Streets and Godfather

II really drew on his Italian heritage and life

growing up in Manhattan's Little

Italy.

That

background served him well for appreciating A

Bronx Tale and transforming Palminteriís story into

something both personal and universal.

In

anticipation of the sophomore festivalís schedule from April

3rd to 7th, 2014, De Niro detailed the development of

this film during a discussion after this anniversary screening. And

since he has a deep love for festivals ó as the founder of the Tribeca

Film Festival in its 13th year this April

16-27th ó it also served a suitable celebration of both

festivals.

This

Q&A is based on the transcript of the nightís talk.

Apparently Chazz decided that if he was ever going get a good part he

would have to write

A

Bronx Tale for himself ó and perform it, first as a one-man

off-Broadway production. How did you come across his wonderful play that

you eventually directed as your first movie?

He

did, exactly. He was doing this one-man show when I was in LA. [I] heard

about it and then saw it. We started talking about my doing it as a

director. It was a long process.

Chazz

had received offers to have the film done and turned them down. What was

he waiting for?

Chazz

had received offers to have the film done and turned them down. What was

he waiting for?

He

wanted to make sure that he could play the part of Sonny in the movie. I

said to him, ďWell you have a lot of offersĒ and it seemed at the time

he did. In Hollywood everyone wants something and itís a feeding frenzy

for a certain thing. At that time this was what A Bronx Tale was

for movie studios the way as I understand it.

So

he had the piece that was given lots of attention. I said to him, ďIf

you want to be able to play the part of Sonny, itís going to be tricky

because theyíre going to buy it from you if you opt to sell it to them.

At the end of the day, theyíre going to want to have someone with a name

to hedge their bets. Theyíre going to probably come to me. So letís

just eliminate that whole process and tell me that youíll give it to me

to direct and Iíll promise you I will guarantee you that you can play

that part.Ē

Thatís what happened. We had Savoy Pictures at the time wanting to do it

and they were more likely to agree to the terms. Thatís how it started

and how it happened.

You hadnít directed movies before. What made you want to do this?

I

wanted to direct a movie for a while and wasnít sure what I was going to

do. I realized that you always want to tell the perfect story. To make

your movie your letter to the world. Iíd say itís not quite what Iíd

imagined as my letter to the world, but itís a movie I understood and

liked. If nothing else, itís something that I wanted to do as my first

film and commit to doing it.

It

was a practical move. I liked Chazz and the nature of it and all this

stuff. I could at least attempt to make something special out of this

material from my understanding of that world.

At that point, you were coming off an amazing six-film collaboration

with Martin Scorsese. Were you concerned that expectations would be too

high?

I

didnít care about all that. Who cares about the comparison? It was about

just doing my thing. The movies that Marty and I had been doing to that

point were wonderful experiences. But my doing the movie as a director

with this material as it happened to be with Chazz was what it was. [It]

had nothing to do [with anything Iíd done before]. It just happened to

be of that subject that I happened to have a little bit of understanding

of.

I

was happy to do it and take my chances. In my world, when you want to

direct a movie, you jump in and take the leap of faith of directing.

Finding a director of photography and all the other people, the

department heads of a film and then going ahead, moving forward and

shooting... it is a big step. To me, thatís what I needed to do and did.

What

did it take getting used to that?

What

did it take getting used to that?

The

first day was a tricky one, because I had to work with kids on a stoop.

Iíve directed kids before, so I had an idea of these kids. I donít

remember now what I did, but I got them to do whatever they had to do

for that scene. Somehow it worked out.

Seeing the film 20 years later, thereís still a confidence about it.

Thank you. I remember these kids, I was like, ďWhat am I going to do

with them?Ē Theyíre all jumping around and everything. These kids... to

get them to do what I wanted to do, I knew I just had to let them do

what they wanted to. Whatever they did within the confines of what I

wanted to do, the parameters. Somehow it would have to work out and that

was it.

How different is your process as an actor from how you direct actors?

I

always feel to direct actors or non-actors or anybody ó I suppose it

could apply to documentaries, too ó you have to let people be

comfortable and feel free to express themselves. That goes especially

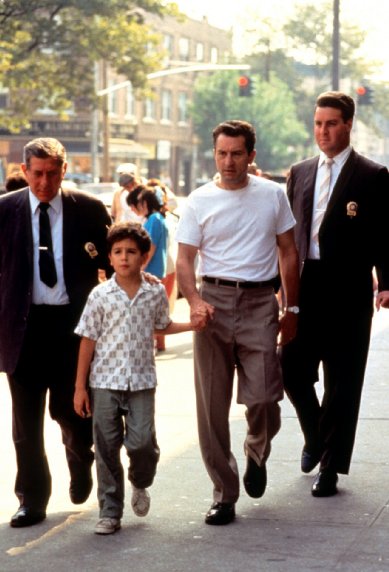

with the case of A Bronx Tale because these are kids. I always

intended to not have be professional actors. You couldnít find

professional actors who wanted to be part of this film.

I

couldnít do it. I had to find kids from that neighborhood who, if

anything, had aspirations to be actors and singers. Who understood the

idea of acting for someone, whether it be for a camera or their mother

or father or family member. Kids who understand that. That was my

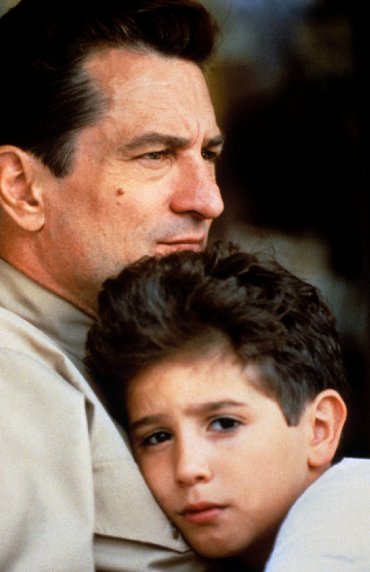

intention, to find those kids and have them be in the film. Like the boy

who played my son who was 12, Francis, he said, ďYou want me to cry?Ē

and I said, ďHold off.Ē

This

was at two in the morning. He understood the meaning and reason and

importance of that emotion and was ready to do it. I was amazingly

surprised how he understood that at such a young age and how important

it was to the film. And he was ready to do it. It was great.

A

number of actors have become directors. A lot of this film is about

people looking at each other and being looked at. Does this come from an

actorís sensitivity?

I

think all actor/directors have an innate sensitivity to other artists.

The actors who are being directed by them understand that because

theyíre being directed by other actors. Theyíre going to give them more,

unconsciously or subconsciously or whatever. Itís always there. If you

have any kind of common sense as an actor directing other actors, youíre

going to be sensitive to that because itís right. Youíre going to get

better performances, more sensitive performances, because the people

working together understand each other.

Itís

has very funny moments and a lot of sweetness. How did you get the whole

shape and tone of the film?

Itís

has very funny moments and a lot of sweetness. How did you get the whole

shape and tone of the film?

I

thought about how these were kids and... again, not using real actors...

you have to use kids from that environment who understand it and can

improv. But these are kids who are 14, 15, 16 and who want to be men. In

that culture, they want to be grownups. They aspire to what they see

before them in the gangster culture and all that stuff. You have to get

kids who understand that world. You donít worry about getting a

professional kid who came from some agent. Thereís nothing wrong with

that, but this is about real people, where itís unspoken and understood

what this is all about.

To

me that was the most important thing. Kids who are 13, 14, 15, 16, who

want to behave and be adults and aspire to what they see around them in

their culture. Which is the Sonnyís culture, the gangster culture.

Your film

GoodFellas dealt with the same idea.

GoodFellas

was about the same thing with Henry Hill. There was no difference. The

characters in A Bronx Tale aspired to the same thing that Henry

Hill did. Itís just that Henry Hill was in Queens and this is in the

Bronx.

You dressed up Astoria for the movie, so what was it like shooting in

that neighborhood?

That

block on 30th Avenue ó that church ó was the same as in the Bronx. Part

coincidence, part design. There were abandoned stores on that block,

which helped us. We could use the funeral parlor, the back part and

downstairs cellaró all of that. We had all these and it was perfect. If

you had to go for a reshoot, things were ready. Weíd go down to the

store we used before for this or that. We were very fortunate in that it

was like a little back lot.

Thereís a deli there that still sells the ďDe Niro Hero.Ē

I go

there and I get one for a nickel.

The music in the film was another part of its character as well.

The

music is the third character, if you will. It was very important to me

that we had the right music. I love the music from that period because

Iím from that time. Well, Iím actually from 10 years earlier, the jazz

is like eight to 10 years younger than me, but we blended those periods

together. I spent a lot of time with jazz and one of the composers of

the play, [Butch] Barbella, weíd sit on weekends and listen to music;

the obvious stuff, though I was always looking for something a little

more obscure.

At

the end of the day, it was about what worked for the movie. Sometimes it

would be something that was so popular from that period, less popular at

the moment, and then you might hear it on a commercial, but it was so

right for the movie that we had to use it. You knew what was right as

you went along. It was hunting, pecking and listening for hours and

hours.

Were

any other movies models for you?

Were

any other movies models for you?

No

other movies at all. It wasnít a Scorsese movie influence. Marty does

his movies, I do mine. I just followed what I thought was right for the

movie and it was that simple. It had nothing to do with anything before

or after or anything like that. No influence.

Itís

my love for movies and for music of that period, or five years after.

That whole period was a little bit of fudging of time because the jazz

period was ten years later but it was all about the love of the music

and the period.

What did you see as some of the themes of the film? The theme of being a

father for example.

There was the father-son thing and thatís the bottom line. As an actor,

Iíd go more for father parts, then grandfather parts. As long as Iím

around, Iíll be offered grandfather, great-grandfather parts.

You just made a film about your father.

I

did. I made a documentary about my father.

I

guess weíll have to wait to see it?

Yeah.

Was that a difficult film to get off the ground?

Theyíre all difficult. Making a movie is very difficult, whether you

make it for a million dollars or 50 million dollars or 100 millions

dollars. Theyíre all difficult. Thereís so many moving parts, one cannot

imagine. Many people have many opinions that you have to field all the

time. Itís just difficult.

Itís

a collaborative effort, a communal effort. Itís complicated and you have

to be able to deal with all that. Take in everyoneís elseís opinion and

deal with everyone elseís input and come out with the final outcome.

Thereís so many films that come out around this story that feel dated

but this one doesnít.

I

donít know if youíre just being nice...

Itís true.

I

didnít think of other films. I just thought of telling this story,

Chazzís story, the story of these kids. Itís a true story. Thatís how it

was in those neighborhoods.

At this point in independent film, you see a lot of movies trying to be

hip that donít stand the test of [history]. Maybe you just didnít care

so much about that.

I

didnít care and was assured of what I was doing because it was what it

was. It was Chazzís story, a good story, a true story, a real story.

Being an adaptation of a play, what did you change from it being

onstage?

Well

it was an adaptation of his one-man show with the characters. He wrote

the script and we used the script to do the movie. It was pretty simple.

He added some characters. I was looking for people in certain

neighborhoods like Little Italy and all around. I found someone and I

said, ďChazz, where is this guy, little Mush?Ē and he said, ďHeís in the

Bronx.Ē I said, ďWell, can we find him?Ē He found him, I met him and I

said, ďLetís use him.Ē

We

did and he was great. We used real people when needed because you canít

replace real people. You cannot add an actor to recreate something that

a real person can do to add the texture to what that life is about. So

when you have that opportunity, you must take advantage of it.

Obviously you were happy with the finished product, but was there

anything you would have change in it if you could?

Thereís always something you want to change, but I was happy with what

we did because I tried my best.

How do you decide when and what you want to direct?

For

The Good Shepherd, I had always been interested in that subject

matter. Eric Roth had written that script. I said I want to do this

because I wanted to do this subject matter. And we did. I wanted to do a

sequel to it, but he hasnít come up with that thing. We dillydallied

with doing it for television, which means we would have more time to get

into the details of the intricacies of that world.

In a

feature, you have less time to do that. But itís more grand; it like

opera. Itís unresolved at this point, but I donít know if I ever do

another movie. If I did five in my life, Iíd be happy. If I do three. I

donít know if Iíll do another. Itís a lot of work. Itís very tough,

especially if you care about it. Itís an uphill battle. Itís always

about money and about budget. You have to constantly be fighting it

every second.

Is it hard to juggle so many different roles in this?

No,

the acting was small, comparatively. Some people are directing and

acting throughout. Itís not easy, but itís not impossible. Itís work.

Itís difficult. Which I enjoy doing, but itís tough work.

In 2014, is there anything left, the good and bad, for the real

characters in this story?

Oh

definitely. Definitely. Chazz is not here but he would have his opinion

about that, of course. Where those characters are and what their

positions are today and where they stand racially, absolutely. Thatís

another movie without a doubt.

Was the two-part structure something that was also on stage or was that

something that was modified?

The

racial thing was what it was. It was always constant.

How much time elapsed between when you first saw Chazzís one man show

and the beginning of filming?

Iíd

say somewhere between five and six years, but I could be off by a year

or two.

What took up most of that time?

My

getting ready to do it. Chazz finally agreeing to it. Allowing it to be

done. The way I remember, I could be off about certain things, but he

wanted the guarantee that he could play the part of Sonny. I guaranteed

him that. It was a feeding frenzy; they were after him for the thing ó

itís sort of real and some of itís illusion but the studios were after

him.

I

said, ďLook, theyíre going to try to get you to sell the script. Then at

the end of the day, theyíre going to come after they buy it from you.

You want to play the part of Sonny, but once they own it, you have no

guarantee that theyíre going to give it to you. If you give the script

to me, I guarantee you that youíll play Sonny. Weíll eliminate the

middle men for the men who would later be the distributor. Weíll need

them at the end of the day, but not in the first part.Ē I said I would

direct it and we could go from there. Iíd play the father, heíd play

Sonny and thatíd be it.

What lessons did you learn making this film?

It

could be a low-budget film, but the bottom line is youíll feel pressure

about cost and budget. Itís all connected. You have a certain amount of

time to do the movie and a certain amount of money to do it with. You

may have visions to do this and that, but at the end of the day you only

have this much money to do it with.

Unless youíre lucky, from a rich family thatíll give you 100 million

dollars to do a movie, youíre going to have restrictions and parameters.

Itís a good thing in some ways, because it forces you to be creative

within the constrictions you have. Thatís the reality. You have to set

down so many days that you can shoot the story you want to tell, whether

itís five or 35, 16 or 10 and however many hours you can shoot that in

and how many set ups you can do in order to tell the story.

If

you have ten set ups a day and ten days to shoot it, you have 100 set

ups to tell that story. You have to find yourself in all those

restrictions and parameters, unless youíre doing it with an iPhone and

maybe youíre making an American iPhone classic, we donít know that yet.

Maybe itís the new thing. Those are the real problems you have when you

have an investor who wants a return on their money no matter what they

say ó they do it for the art, they do it for this ó they want a return

on their money.

The

more money it is, the more they want the guarantee that at least get

their money back. If itís $100,000 they want their $100,000 back. If

itís a million, they want it back, maybe theyíll make a profit. Itís all

very simple. Thatís the bottom line of it all.

How has your approach to acting changed since you were younger a taking

a more dangerous, method-like way of being?

I

donít know what the dangers are because Iíve never experienced that. If

youíre saying somebody gets too involved in their role where they end up

losing themselves and going crazy, Iíve never seen that ever. Ever.

As

actors, the best thing you can do, I feel, at the end of the day, actors

use whatever can work for them. When theyíre in there for the moment,

you have to use whatever is good for you. Think about your mother who

died last week or think about this or that, you can do whatever.

The

two things are: you donít hurt yourself, and you donít hurt others.

Everything else is okay. Whatever your wildest imagination is that can

make you arrive at that point in that scene, thatís fine. But the rest

of it is all bullshit.

Everyone has a way of arriving at that thing and no matter what they say

or what lip service they give to it all, thatís the bottom line. I have

great respect for all of them but thatís the bottom line. You have to

choose for yourself.

When

youíre in a scene, you say what does this scene mean to me? What does

this character mean to me? You have to interpret it. You have to let it

be personal to yourself. Thatís the most important thing.

CLICK

HERE TO SEE WHAT ROBERT DE NIRO HAD TO SAY TO US IN 2010!

CLICK HERE TO SEE WHAT

ROBERT DE NIRO HAD TO SAY TO US IN 2015!

Features Return to the features page