Copyright ©2007 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

September 19, 2007.

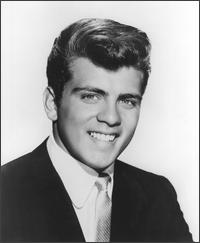

Fabian was born under a

lucky star, and that star first shone its light above the ancient, sooty

row-house streets of South Philadelphia. Although we think of 1950s America

as a world of suburbs, tailfins and sparkling new appliances, most of this

country still lived in cities, in cramped quarters connected by dark alleys

and narrow streets.

Fabian shared a tiny house with his parents (dad was a cop, mom a housewife)

and his two younger brothers. His neighborhood, with its stoop porches and

lack of nature, was as far away from the suburbs, and for that matter,

glamour and fame, as you could get.

Even though the studio which broadcast the daily dose of Dick Clark's

American Bandstand was not too far away, Fabian was light years removed

from the panic, adulation and monster ratings that the program generated.

The closest he got to music was hearing the gang on the corner, about 150

feet away from his house, singing doo-wop.

While millions of teenagers rushed home from school and watched American

Bandstand each weekday afternoon, and while parents and conservatives wrung

their hands over this THING called rock and roll, Fabian was oblivious to

the delirium. He spent his afternoons delivering for the local pharmacy,

bringing medicine to the elderly. He earned six dollars a week, which helped

to support his struggling family.

However, a freak accident and a strange incident was about to change his

life – and his light – forever. The fourteen-year-old who dreamed of someday

being a civil engineer was about to be reluctantly plucked from obscurity

and transformed – literally overnight, lit by a lucky star – into a major

musical phenomenon and one of the earliest influences in rock and roll.

The timing could not have been worse – and could not have been better.

Fabian's father, under the strain of The Job, suffered a major heart attack.

The ambulance came swiftly, and Fabian sat on the stoop and helplessly

watched his father, in a stretcher, being hauled away to the hospital.

Although Fabian was surrounded by his family, he was beside himself, and

freaked. His father, if he were lucky enough to live, would be out of work

for a while, and the money, which was already tight, would get tighter.

Light

years later, in another century, on his spread of twenty acres in

Southwestern Pennsylvania, Fabian recalls that exact moment when his life

would change forever.

Light

years later, in another century, on his spread of twenty acres in

Southwestern Pennsylvania, Fabian recalls that exact moment when his life

would change forever.

He says, "This guy comes cruisin' down the street and sees the ambulance and

the cops. He thought something was wrong with [my pregnant

next-door-neighbor, whom he knew]. So he stopped and got out of the car.

Once he found out what was going on, he kept staring at me and looking at

me. I had a crew cut, but this was the day of Rick Nelson and Elvis. He

comes up and says to me, 'So if you're ever interested in the rock and roll

business…' and hands me his card. I looked at the guy like he was fucking

out of his mind. I told him, 'leave me alone. I'm worried about my dad.'"

The guy, who turned out to be

Bob Marcucci,

the owner of Chancellor Records, did not let up. He kept coming around, like

a bad case of acne. Fabian's father, in the meantime, returned from the

hospital and recovered slowly, unable to work. He was on disability, which

totaled a sickly $45 a week. Add that to the family budget with Fabian's $6

a week.

He says, "So

finally the guy talks to me. He says, 'look, we'd like to try you with a

song.' And I said, 'hey, can I make any money?' My mother was totally

against it, because it would mean me leaving home. My father was saying,

'whatever you want to do, but you have to go to school.'"

For the sake of his family, Fabian signed a record contract, grew his hair

into a pompadour and walked himself into a recording studio.

He went from $6 a week to $36 a week (that's $30 a week allowance from the

record company and he also kept his pharmacy job, along with his full-time

studies at South Philadelphia High School).

"I didn't know what I was doing," Fabian says, "but I knew my goal, to try

to make extra money. That meant a lot to our family. I rehearsed and

rehearsed, and I really felt like a fish out of water. And we made a record.

And it was horrible. Yet it got on [the legendary Philadelphia rhythm and

blues radio program] Georgie Woods. For some reason, Georgie Woods played

it.

"Then I got to meet Dick Clark. He talked to me for a long time, and then

put me on the show. The daytime show, before it went national. The response

– they told me – was overwhelming. I had no idea. All during that period, I

was doing record hops. Not getting paid for it, but for the record company

promotions. Just lip synching to my records. The response was really good.

"Finally, Mort Shuman and Doc Pomus, who did records for The Coasters, The

Drifters, and Elvis, gave me a song called 'I'm A Man.' It hit number 40 on

the charts. Then things really went well for me. I guess the rest is

history."

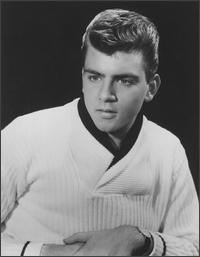

Let's

then put this into a historical perspective: at the dawn of the rock and

roll era, on the brand new medium of television, and radio's new second life

as a Top 40 record-promotion vehicle, Fabian went, to say the least,

supernova (fueled by the light of the lucky star).

Let's

then put this into a historical perspective: at the dawn of the rock and

roll era, on the brand new medium of television, and radio's new second life

as a Top 40 record-promotion vehicle, Fabian went, to say the least,

supernova (fueled by the light of the lucky star).

His first hit was followed by a triple-punch of "Hound Dog Man," "Turn Me

Loose," and "Tiger," all penned by Shuman and

Pomus and all monster

smashes.

Adulation poured in by the mailbags. Mobs formed around him. His pompadour

was pulled by hormone-enraged girls.

"I was a little awkward and a little uncomfortable at times," he recalls.

"But I had a goal. I only had one goal. It wasn't fame. It was money, for my

parents. I thought it was all bullshit. They put me in white bucks. Tight

pants. Revealing shirts. But I knew I could endure this."

The lucky star was shining, all right, but with mixed signals.

"My father was all for it because it took the burden off of him," Fabian

says. "My mother was always a little leery. She made sure I finished high

school with tutors. I wanted to [finish school] anyway. I didn't care for

leaving school. I did well in school. But once I was determined to stay

around, because of my family, I rehearsed very hard.

"The only way to get over stage fright is to know what you're doing. And to

get out there and do the best you can, and feel it. You have to really feel

it. Cutting records did feel good. What kid didn't like rock and roll?

[Before all of this,] I only sang with the radio, like every other kid."

Now, the nation was singing along with him, watching him on television and

pumping nickels into jukeboxes to hear his songs. America helped lift him to

the very heights of that lucky star that shone upon him.

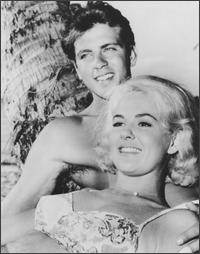

Among those watching his appearance on the top-rated Ed Sullivan Show

was Irwin Allen, a producer for 20th Century Fox who would later

go on to produce classic disaster movies like The Poseidon Adventure.

He signed Fabian to a seven-year movie contract. However, Fabian went on to

appear in over thirty films, including North To Alaska, The Longest Day,

and Ride the Wild Surf.

"Seeing myself on the big screen for the first time," he recalls, "I just

about died. I went to the premiere of [his first film] Hound Dog Man

in Philadelphia. I'm sitting there in the dark, and I love movies. To see

myself on screen, twenty times bigger than I am in real life, I just sat

there in awe. I just couldn't believe that I was up there.

"The

acting wasn't like the singing, because it was very private – quiet on the

set. No screaming [teenage fans]. It was a wonderful experience. I got to

meet and work with John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, and Peter Lorre. Elvis came

over to meet me when I was on the lot. Marilyn Monroe was on the lot.

Natalie Wood. Gary Cooper came over. I was on the plane with Marlon Brando

for eight hours coming back from Tahiti.

"The

acting wasn't like the singing, because it was very private – quiet on the

set. No screaming [teenage fans]. It was a wonderful experience. I got to

meet and work with John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, and Peter Lorre. Elvis came

over to meet me when I was on the lot. Marilyn Monroe was on the lot.

Natalie Wood. Gary Cooper came over. I was on the plane with Marlon Brando

for eight hours coming back from Tahiti.

"The only time that ego got involved was when anybody tried to fuck with me.

Then I would stand my ground, because I'm a kid from South Philly. I would

just speak my mind. For instance, if somebody would try to use me for their

own purposes. The only person I wanted to protect was my mother. Not to

shame her. My father would always say, 'just don't shame your family.' That

was always in the back of my head. It's a whole different ballgame today. I

don't know how [young stars] do it today, unless they live like monks."

Although Fabian found his passion in acting, his taste for the record

business was short-lived. This was convenient, since most teen idols have a

shelf-life of about eighteen months.

He says, "I quit the business when I was eighteen. I just had to get away.

My South Philly came out in me and I bought out my contract. Then I just

concentrated on film. After all the big films, I hit a very low period. I

had children to support. So now I had another family to support. First, it

was my parents, now it's my own family. So I had better get back on the

road. So I put a little band together. In fact, it was a Mormon band. The

greatest rockers you ever met. And we started getting booked. By my late

twenties, it was a very difficult time of my life, but I had

responsibilities. It was a horrible time."

Like most fifties performers attempting to survive in a post-Beatles world,

circumstances were hellish. America had turned its back on them. Gigs, if

they would even present themselves, were often low-end and humiliating.

By the early seventies, however, that lucky old star appeared again. Thanks

to Dick Clark opening up his nostalgia vaults, and the success of Grease

on Broadway, as well as American Graffiti in the movies, Happy

Days on television, and oldies formats on FM radio, the fifties were

back. And actually better than ever.

At

long last, Fabian was in great demand again. He teamed up with his former

teen-idol contemporaries, Frankie Avalon and Bobby Rydell, as "The Golden

Boys of Bandstand." They've been playing Harrah's in Atlantic City for over

22 years.

At

long last, Fabian was in great demand again. He teamed up with his former

teen-idol contemporaries, Frankie Avalon and Bobby Rydell, as "The Golden

Boys of Bandstand." They've been playing Harrah's in Atlantic City for over

22 years.

He says, "When I can, I still do about twenty shows a year with them. If you

think about it – I mean, if you really stop to think about it, it's mind

blowing. It's really incredible how that era has left its imprint on

society. To have that kind of longevity, nobody would have bet on it."

As well, he produces a show in Branson, Missouri with his friend and fellow

former teen-idol Bobby Vee. It's at the brand-new Dick Clark American

Bandstand Theater, for two weeks every month, from April through November.

"When I do that show in Branson," he says, "what is truly beloved is not

especially us, it's that era. That's the most important thing that I feel on

stage. These people come to relive their youth and some really great trends

in their lives. They look at us and they say, 'we've all made it.' It's not

just that I had survived, it's that we all had survived. For people my age,

we've seen a lot happen in the world. So many things have changed. And we're

still around. For some of us, it's been really hard, getting to where we are

today. I've certainly had up's and down's in my life. And my audience has

been through the same thing. But at our show, they turn sixteen all over

again. These are very vibrant people. They're still dancing in the aisles."

Now, at a comfortable and content 64, he spends his downtime with his wife

at their Pennsylvania home, with his dog Max and other assorted animals.

"I don't see a soul except critters," he says. "I like being out of touch

here. I'm a bit of a loner."

Yet he still feels connected. In addition to reading four newspapers a day

on the internet as well as historical novels, he muses, "I'm proud of my

show, because I own it. I'm proud of Bobby Vee. Bobby is an incredible dude,

man. Bobby and I have been friends for years. It's really like a family,

because we all interact with each other on a weekly basis, as opposed to

doing one-nighters."

His

two children are grown (his son, Christian, is the acclaimed screenwriter of

Albino Alligator and Deep in the Valley, and had just given

Fabian his second grandchild.).

His

two children are grown (his son, Christian, is the acclaimed screenwriter of

Albino Alligator and Deep in the Valley, and had just given

Fabian his second grandchild.).

Does he ever get tired of telling his 'discovery' story?

"Of course I do," he says.

Does he believe in that lucky star? Not necessarily.

"You make your own luck," he says.

It's debatable, of course, when you consider his recent car accident, in

which the car he was riding, along with his manager and daughter, was cut

off by racing teens. The car flipped over three times.

Although everyone

involved managed to survive, thank goodness,

the cop said he had never seen anybody walk away from an accident

like that.

After its triple flip, the car landed right in front of a billboard for his

appearance with "The Golden Boys of Bandstand."

Lucky break. Smooth landing.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.

Features

Return to the features page.

Copyright ©2007 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

September 19, 2007.