Copyright ©2007 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

May 26, 2007.

Nathan

Englander's first novel, The Ministry of Special Cases (Knopf) is a

shattering experience, told in a deceptively simple manner. In it, a Jewish

family in 1970s' Buenos Aires is torn apart when their college-age son is

taken away by the government, along with thousands of others, for reasons

that are not given.

Like

that, he is "disappeared," as it is called, almost as if he never existed at

all.

The

emotional and bureaucratic nightmare that ensues spirals you down through

the seven circles of Hell. In trying to track him down, get him back,

persuade

government officials – or even neighbors and friends – to talk or give the

slightest clue of his fate – tests the resolve of the boys' parents on every

level, from psychological to financial.

These

humble but strong people stop at nothing – not even the threat on their own

lives – to find their son and bring him home.

Fiction?

Hardly. This particular account is indeed fictional, but it is set against

the dark chapter of Argentina's so-called Dirty War (1976-1983). During that

time, thousands of citizens were "disappeared," most likely in the name of a

paranoid right-wing government desperately afraid of revolution and trying

to keep control.

Most of

the disappeared have never been recovered, and their whereabouts remain a

mystery. This tragedy has left behind a grieving living mass of destroyed

families in Argentina and even beyond, in neighboring countries. These

relatives will never feel whole again, will never know closure; they still

demand answers, all these many years later. Even today, with DNA testing and

a sympathetic media focused on the event, resolution is all-too slow in

coming.

To add

salt to the wound, the government officials allegedly responsible for these

crimes have been mysteriously pardoned by the succeeding government. And it

has been recently discovered that Washington gave The Dirty War its

blessing. Even Secretary of State Henry Kissinger encouraged the actions in

1976 (warning the Argentines doing the abducting that they should act fast,

before the American Congress is back in session).

Nathan

Englander – this being his first novel despite being far from the action –

pulls off quite a feat. Raised on suburban Long Island as an Orthodox Jew

and now living in Manhattan as "radically secular," he makes the sweaty

nightmare feel unbearably real.

Nathan

Englander – this being his first novel despite being far from the action –

pulls off quite a feat. Raised on suburban Long Island as an Orthodox Jew

and now living in Manhattan as "radically secular," he makes the sweaty

nightmare feel unbearably real.

He first

drew attention to his honest and boldly told stories in The Atlantic

Monthly and The New Yorker, as well as The Best American Short

Stories and The O. Henry Prize Stories. These stories were

collected in his well-received For The Relief of Unbearable Urges.

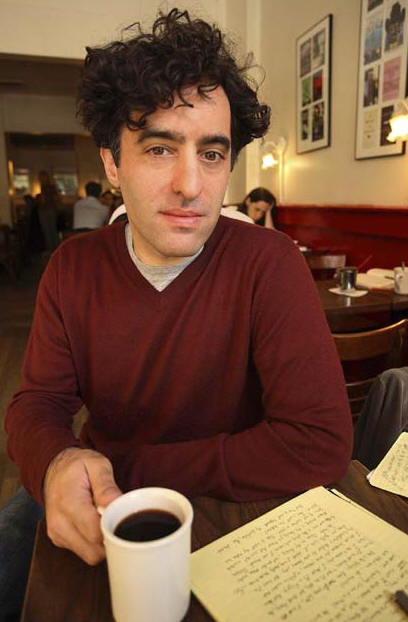

On a

beautiful spring morning at the Hungarian Pastry Shop near Columbia

University, we discuss the book and the fact that history can repeat itself;

that, as we have learned from the war in Iraq, even the most perverse

actions of a government can become ordinary and matter of course.

You are not from

Argentina and do not have any direct association with The Dirty War, and yet

your novel makes the reader feel like you've experienced it first-hand. How

did you pull this off?

I like a

pressurized story, this idea of a family unit being forced to have these

growing pains together.

I also

wanted to look at a community where certain people pretend that other people

are pariahs. Yet the community can't actually exist without these so-called

pariahs. They pretend they have this great shame of them, but [the

community] wouldn't know who it was without them.

I like

to write "distant." I feel safe at a distance. I partly attribute it to

these Argentine friends I have who grew up in this period. I heard stories

from them and I also didn't hear stories. It was what they weren't saying

that was interesting to me. Years later, I would be sitting in the car with

my [Argentinian] friend, and he would start to talk, and then it would be

three hours later.

You depict the

atmosphere as cold and threatening. Trust no one.

As a

paranoid myself, I like paranoid stories. It's the age-old joke: just

because you're paranoid doesn't mean somebody's not going to get you. Was

Pato [the young character in the book who goes missing] really a

revolutionary, or was it that he just smoked some reefer or he learned some

ideas in school that he spouts? The government then says, "you want to be a

revolutionary? We'll treat you like one."

There is also the

nightmare of government bureaucracy, no matter who is in power.

It's the

frustration of trying to get stuff done. When I moved to Jerusalem, I had a

very similar experience [with government bureaucracy]. It could be so

overwhelming. I'm not even talking about government oppression. I'm talking

about getting that parking sticker, or just signing up for that bank

account. So I became interested in what it would be like to live in that

kind of world.

The

book address relationships on so many levels, from deeply personal family

bonds to community prejudices to how a government treats its people.

The

book address relationships on so many levels, from deeply personal family

bonds to community prejudices to how a government treats its people.

The book

is so many different things to me. I was just getting yelled at by someone

who said that the book is really about fathers and sons [and not a political

story]. I wasn't writing a warning book. I wasn't writing a political book.

I was telling this story that takes place during The Dirty War, but

hopefully all of those other things feed in.

The story takes place

in the not-too-distant past, where it's rather shocking – in a modern day

and age – that such fascist tactics can be applied to a contemporary people.

The book

is really about time, a continuum. How much do we use hindsight? Everything

is history. Even the Holocaust happened under the most modern circumstances

for the time.

People

[in North America] tend to think of [people in South America] as so distant

and so foreign, but they have a functioning middle class there. In that

story is the element of the need to "move up." You need that option – that

dream – of getting somewhere.

How did you manage to

put such a complicated story together and tell it in such a clear and

concise way?

I wanted

to build my story first, and then I have this very strange process where I

research after the fact.

For

instance, I had a character kicking a can of soda down the street, and in my

research, I discovered that they hadn't had canned soda in Argentina until

1983 or something like that. I don't want to spend ten years on a book and

then bum an Argentine reader on page five about something that should have

been knowable and do-able [to me]. I feel that is the writer's obligation.

Anything

I make up I make up and anything I alter I alter. I want to know if it's

right. This book is all about what it is to love a city, and I want it to

be right.

Anything

I make up I make up and anything I alter I alter. I want to know if it's

right. This book is all about what it is to love a city, and I want it to

be right.

This is a fictional

account of a frighteningly real event. The legacy of the Dirty War in

Argentina presents grieving families still looking for relatives who had

disappeared decades ago.

That's

the horror of all of this. It's the way they talk about Iraq now. That's

when you understand when you have chaos. The numbers of missing could be

anywhere between four (thousand) and thirty-thousand people. I mean, what is

it? Give or take twenty thousand? It's insane. They are still finding stuff.

They are still digging. They are still doing DNA testing. They are still

looking. It doesn't end. I just went down there two months ago and wrote an

essay about it. It's shocking to me that there are people still looking for

their kids and grandkids.

After ten years of

working on this project, how does it feel to finally have the book in

print?

Strange.

It's like having a new identity for just this period. That's all. It's like

building another version of me for a little while.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.

Features

Return to the features page.

Copyright ©2007 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

May 26, 2007.