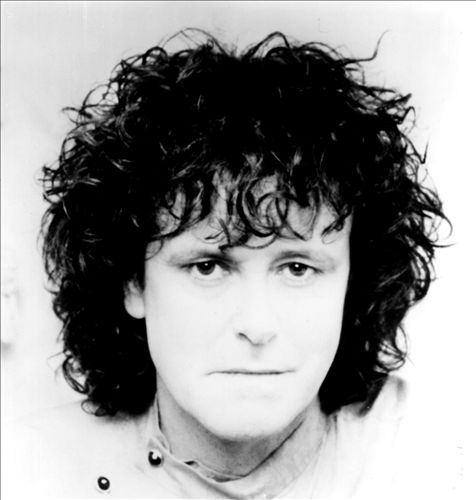

Originally branded

a Dylan-wanna-be, Donovan quickly transformed into "Sunshine Superman"

and defined a decade.

For Donovan Leitch, his long-awaited induction into the Rock and Roll

Hall of Fame calls for an inner celebration as well.

"It's a singular honor and an extraordinary thing," he tells me when we

hook up in a Fifth Avenue penthouse, where he and his wife/legendary

muse, Linda, are staying as the coolest guests ever. "It's the greatest

beam or searchlight on any artist's work on the planet. It's like an

Academy Award."

Yet knowing Donovan,

the author of such Sixties superhits as "Mellow Yellow," "Sunshine

Superman" and "Hurdy Gurdy Man," it's not only about the party and

getting high-fives from high admirers. There has to be a deeper

meaning.

"The induction needs

a celebration of the inner journey to self awareness," he insists. "You

can't separate the inner life of my work from the outer."

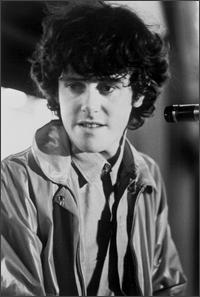

So he says, and the thought runs deep, even though he was originally

dismissed as a Bob Dylan clone. As early as 1965, he scored Top 40 folk

hits like "Catch the Wind" that sounded amazingly like Dylan but were

really borrowing from Guthrie. By 1966, he was on par with The Beatles,

who themselves were morphing into something new and quite different.

They were brewing something alien to pop music and rock and roll radio

in particular. It transcended the usual DJ patter and teen-idol

blandness. Suddenly, God was in Top 40 music. And so was Donovan.

It was more than just

music. It was lifestyle. It was mantra.

"All those years

ago," he says, "me and The Beatles were pursuing promotion of meditation

as a possible peace tool for the world."

That world, as

Donovan had known it from his working-class roots in Scotland and his

rustic teenage years in England, was so new, it was actually old.

"I

see the Sixties as a renaissance period," he says, "like in Italy and

France, where certain lost things were again found. Obviously, the world

in the Sixties was in a crisis situation. Millions of people were born

after the second world war and let loose on the world, and the world was

very clearly televised."¯

"I

see the Sixties as a renaissance period," he says, "like in Italy and

France, where certain lost things were again found. Obviously, the world

in the Sixties was in a crisis situation. Millions of people were born

after the second world war and let loose on the world, and the world was

very clearly televised."¯

True enough. They say

the revolution was coming, and would indeed be televised. In living

color would come a new heaven on earth, where the meek (and the high and

the lovers of flowers and peace), would do the inheriting. It would be

ushered in with the shake of a tambourine.

He says, "Soon you started hearing, especially on my album Sunshine

Superman, an alternative society appearing in the songs. The Sixties

are a time when poetry is returned to popular culture; when poets return

to popular culture. Poetry is a highly evolved form of language. It's

different from prose. Prose is matter of fact. Music and poetry used to

be one. Then they were separated over the years. It came in again

[during the Sixties], through the ballad form."

The record industry, and then even pop radio, would drift into a heady

haze, and the old guard found itself floundering. By 1967, Donovan, The

Beatles and Dylan were ruling the charts, and their lyrics seemed to be

understood only by the

most spaced out of youth. There was nothing mainstream about it, and

yet there it was, in the mainstream.

"Folk music would

invade the popular culture," Donovan says. "That's how the meaningful

lyric would arrive, and the ballad poet, Dylan of course, would use the

ballad form. Poets would reappear in the guise of pop music."

By 1967, the Top 40

was groovy with this new/old discipline, yet station programmers

–

and the FCC

–

were nervous. It was a far cry from Chubby Checker and Frankie Avalon.

Songs began to show some funny smoke, and refer to acts of love more

serious than just holding hands.

Yet, as

counter-culture as Donovan was, he did not wander too far from the

mainstream and the pursuit of the beloved hit record.

"I wanted to relate

[create hits]," he says. "It seems to me that in the folk world they

were dead against popular music. But I felt that they needed all this

music that was coming out of bohemia: this was peace and brotherhood. It

was important information. Dylan signed a deal with Columbia. He didn't

sign a deal with a folk label. He saw the possibilities in appealing to

a mass."

His songs, even to

this day, are used in advertising to Morse Code counter culture. Donovan

is OK with that. The connection to the Sixties is beyond understood.

His songs, even to

this day, are used in advertising to Morse Code counter culture. Donovan

is OK with that. The connection to the Sixties is beyond understood.

He says, "What this

beam of light on my work does, quite simply, is it brings in an

extraordinary new audience, which is why I embraced very early the use

of my music in commercials, TV and film."

If you thought his

was an act, think again. His spirituality is the real thing.

"There is this

higher level of consciousness that

hasn't been developed and can be developed and if it is accessed," he

says, "and if you look at things from a different level of

consciousness, you will see the solutions arise. Why people can't see it

is because they are stuck, fixated."

Helping to get the world unstuck is Donovan and his mystical BFF, Deepak

Chopra, the Indian-born spiritual advisor. They've been friends since

the days of The Beatles and The Maharishi, and recently they reunited in

New York, to answer questions and question answers.

"Deepak and I have known each other quite well over the years," he says.

"I have joined him on stage for his presentations. But we've never

before had a real Q and A. And we've experienced so many similar things

during our lives

– people we know and things we've done. It was not so much

an interview as a conversation between us."

Although Donovan's music lives on, he insists that it remains fresh as a

daisy.

"It hasn't dated," he says. "It's fresh and it's alive. I was surrounded

by acoustic instruments, and there is something about that that will

never date. It has that feeling of it's happening now."