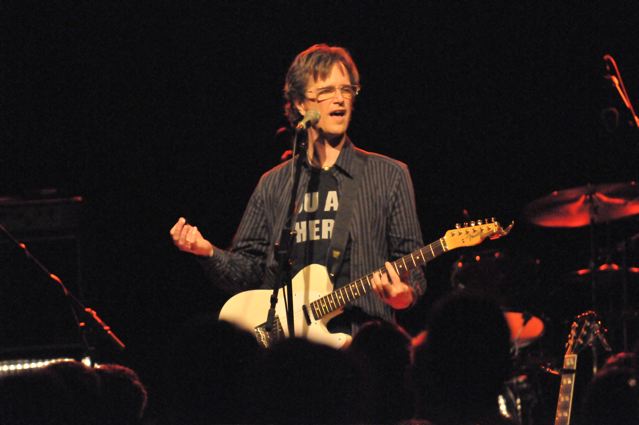

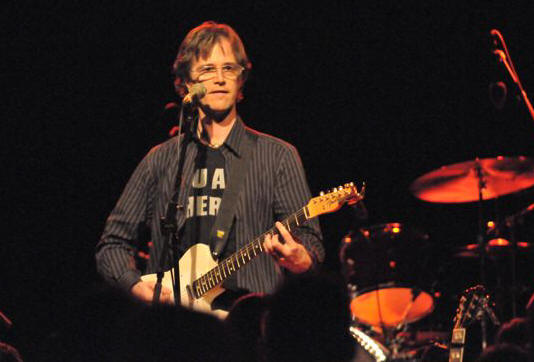

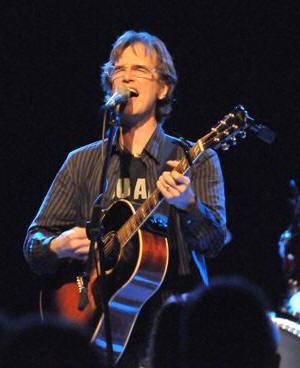

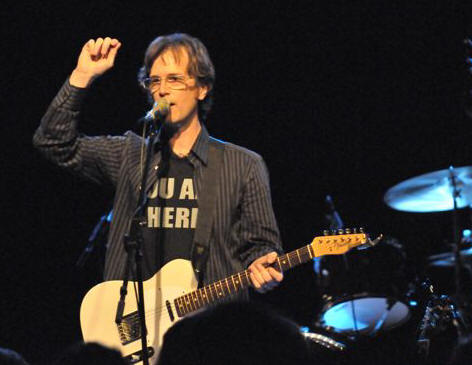

Almost two decades into his music career, Dan Wilson has finally

released his first solo album. However, he had been out in the music

world making waves long before the recent release of Free Life.

The years have brought Dan Wilson extended gigs in two acclaimed bands,

the chance to sing one of the most recognizable hit singles of the late

1990s, a celeb fan club which includes Sheryl Crow and the Dixie Chicks

and a co-writing credit on the 2007 Grammy winner for song of the year.

Free Life

is a labor of love

five years in the making. Not that Wilson was fooling around in the

studio fussing over everything, but he was busy trying to capture his

musical vision as well as working on the side as an in-demand songwriter

and producer.

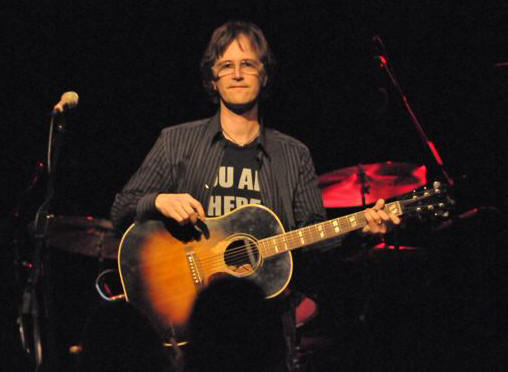

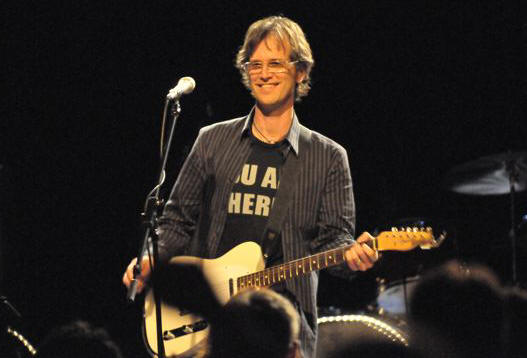

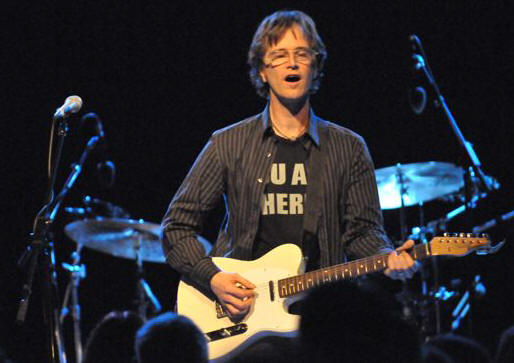

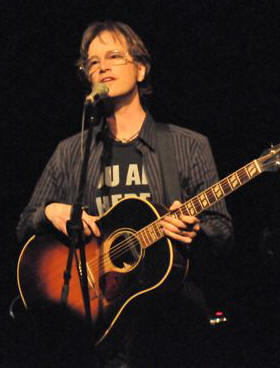

“When I started the album, it was 2002,” Wilson recently recalled

backstage awaiting a show at the Fillmore at the TLA in Philadelphia.

“I worked on it for about three and a half years and then I got stuck in

record business bullshit for about two years. When I first started

working on the album radio really sucked. I think the things that were

hits in 2001 and 2002 were terrible. Terrible. Britney Spears and a

lot of stuff that was just, just… like nice, you know. Fun to

listen to, enjoyable, but really just very light. Everything was just

so light. Even the heavy music was light.

“At that time I didn’t have any thought of writing something that could

be on the radio, because it just seemed all so very trite to me at the

time – and tedious. I just wanted to make the greatest, most soulful

songs I could possibly make and just create a mournful, beautiful

sound. Do something that people could really just completely fall into

and get enveloped by – a sound that could bring you to another place. I

don’t know if I sound any more like the radio now, but things on the

radio sound better for me now – by a long shot – than they did when I

started the record. So I’m glad I didn’t try to go with the trends of

the day at the time.”

At that Philly concert, Wilson opened for popular alt-country singer

Kathleen Edwards, who marveled that despite all the stellar work Wilson

has done over the years, many people there did not know who Wilson was.

“He’s a great guy. He’s a great songwriter. I should be opening for

him,” Edwards stated flatly from the stage.

However, it sort of makes sense. For Wilson, the music is the thing

more than fame. Even when he was selling millions of disks with his

second band, Semisonic, Wilson shared the spotlight as just one of the

guys in the band – even though he had complete creative control of the

group.

However, it sort of makes sense. For Wilson, the music is the thing

more than fame. Even when he was selling millions of disks with his

second band, Semisonic, Wilson shared the spotlight as just one of the

guys in the band – even though he had complete creative control of the

group.

Music had always seemed a reasonable goal in life for him. Wilson grew

up in the Minneapolis area as part of an artistic family. His father

was also an aspiring singer; in fact he was in a band that got as far as

recording a single.

“My brother and I were probably very much influenced by the fact that

our dad had a singing group when he was a kid. They were called The

Four Lords. All harmonies. That probably made the whole thing seem

kind of doable or available,” Wilson says.

His brother Matt went on to form the critically acclaimed late 80s-early

90s band Trip Shakespeare. At the time that Trip Shakespeare had

released their respected debut CD Applehead Man, Wilson had been

in bands but was not focusing on music as a career.

“This was when I was living in San Francisco, being a bohemian painter

and crying a lot and not knowing what I was going to do with my life,

but painting a lot,” Wilson recalls. “Matt, meanwhile with his trio

made this album. The scheme that he came up with for arrangements was

he had a left guitar and a right guitar. He played both guitars in the

mix. He called me and pitched me on the idea of coming back from San

Francisco to Minneapolis and playing the right guitar for live shows –

to be part of the band. So I just learned… I had never played guitar in

a band before. I’d played bass in a lot of bands. I really studied

hard and learned all of his parts.”

Wilson went on to record three albums with the group – Are You

Shakepearienced? (1989), Across the Universe (1990) and

Lulu (1991). While the group garnered a rabid following amongst the

alt-rock intelligencia and a solid fan base, it never quite translated

into record sales.

“We mastered a lot of the elements of live performing that most people

just can’t do,” Wilson recalls. “We figured out how to play extremely

dynamic shows, how to jam really interestingly and excitingly – when

nobody else was jamming. We really were interested in improvisation.

We learned how to sing in tune with our harmonies. The songs were

always very colorful and vivid and strange. But we never found a

collaborator that could help us translate that vision into a sound-only

recording. Although I’m proud of those albums and I think there are

great things on them, I think we never quite figured out how to make

that transition. There is a difference – two different media…. We made

a living for several years and put out lots of records. Personally, I

was not frustrated or humiliated by the lack of radio matches for Trip

Shakespeare. I’ve always kind of known what a radio song sounded like

and I could tell we weren’t making them. I don’t know if the other

people in the band thought about this or not. Matt used to tease me

that I listened to the radio too much. I could kind of tell that what

we were doing was not going to be played on the radio. It never really

bummed me out that we never had any hits because it was sort of obvious

we weren’t going to.”

“We mastered a lot of the elements of live performing that most people

just can’t do,” Wilson recalls. “We figured out how to play extremely

dynamic shows, how to jam really interestingly and excitingly – when

nobody else was jamming. We really were interested in improvisation.

We learned how to sing in tune with our harmonies. The songs were

always very colorful and vivid and strange. But we never found a

collaborator that could help us translate that vision into a sound-only

recording. Although I’m proud of those albums and I think there are

great things on them, I think we never quite figured out how to make

that transition. There is a difference – two different media…. We made

a living for several years and put out lots of records. Personally, I

was not frustrated or humiliated by the lack of radio matches for Trip

Shakespeare. I’ve always kind of known what a radio song sounded like

and I could tell we weren’t making them. I don’t know if the other

people in the band thought about this or not. Matt used to tease me

that I listened to the radio too much. I could kind of tell that what

we were doing was not going to be played on the radio. It never really

bummed me out that we never had any hits because it was sort of obvious

we weren’t going to.”

The writing was on the wall for Trip Shakespeare after Lulu, and

the band fractured.

“The frustrated period of time at the end of Trip Shakespeare when we

weren’t getting along, I think the road had taken its toll,” Wilson

recalls. “We had travelled for five years pretty much solid. 200 shows

a year. It’s a lot of work. To see the same person in a band for that

many years in a row – it gets tough. So Trip Shakespeare ended in a

dark phase. My brother Matt was not happy with how it was going. It

was too democratic for him. I think he would have been happier if he

could have been more of a dictator and just told everyone what to do.

That might have worked better, actually, in the last analysis.”

Matt Wilson decided to work with other Minneapolis-area bands – though

periodically to this day the Wilson brothers and former Trip Shakespeare

member John Munson work together on a side-project called the Flops.

Meanwhile Dan Wilson and Munson hooked up with drummer Jacob Slichter to

form a band called Pleasure, which quickly changed its name to Semisonic

and became one of the big buzz bands of the 90s.

“My friend Jacob Slichter had moved to Minneapolis and was just hanging

out, being a musician there. He was making recordings in his basement

of his own songs. Just for fun, during Trip

Shakespeare’s hardest period, I would go over to Jake’s basement and

we’d write songs together. We wrote ‘If I Run’ and ‘Temptation’

together. I wrote a couple of other songs. We were kind of figuring

out how to make really good sounding recordings on this basement studio

that he had built. At one point, I invited John Munson to play bass on

the songs. I had played bass on a couple of them and it was okay. It

just kind of took off from there. We learned some covers for a party

that John’s girlfriend was throwing. We did a bunch of casual things

that didn’t really seem very serious or committed and pretty soon we had

a band.”

Semisonic signed with MCA Records, and their first CD The Great

Divide came down much the same way that the Trip Shakespeare records

had – lots of critical love, no big hits. Not that it was for lack of

trying on Wilson’s part.

Semisonic signed with MCA Records, and their first CD The Great

Divide came down much the same way that the Trip Shakespeare records

had – lots of critical love, no big hits. Not that it was for lack of

trying on Wilson’s part.

“At the end of Trip Shakespeare I was thinking I’d like to do something

that actually has a chance of being hits,” Wilson says. “I’m a pop

music lover. If I was to name my favorite songs by most artists, it’s

probably going to be one of their hits, you know? It’s usually not some

obscure thing. I like the things that other people like. I was pretty

much determined to figure out how to have the new band be playable on

the radio, so I worked really hard to make that happen on Great

Divide. And people kind of interpreted it as a big art project and

it didn’t have any hits. I got a lot of respect and appreciation for

it. We toured a lot. But there were no hits.”

Wilson realized that maybe he was analyzing it all too much. Music had

always been more instinctive for him, so for the follow-up he just did

what came naturally. What came naturally was Semisonic’s seminal album,

Feeling Strangely Fine (1998), which included the smash hits

“Closing Time” and “Secret Smile.”

“I thought maybe I should stop thinking of hits too much and just sort

of do the art. So Feeling Strangely Fine was more like, I

really, really did try to make it as much of an art project as I

possibly could. So there was something funny when there were a couple

of songs on there that the label eventually decided could be some big,

giant singles. They thought that ‘Secret Smile’ could be really big and

they thought that ‘Closing Time’ could be really big. So that was

actually a pleasant surprise.”

Sadly, now that Wilson had finally reached the level he had been

striving for in his career, he was unable to totally appreciate it.

Just as “Closing Time” started climbing the charts, Wilson had a

real-life wake-up call that made him put music stardom into more

perspective. Suddenly “Closing Time,” a song about barflies being

shooed out at last call, had an entirely different meaning.

“Four days before we started recording Feeling Strangely Fine, my

daughter Coco was born,” Wilson recalls. “She was extremely premature.

She weighed eleven ounces. She was going to be sick for a long time.

She had a lot of medical problems. She was in the hospital for eleven

months, in intensive care for most of that time. So I wasn’t really

thinking about fame and success much. I was just doing my job and doing

my best. The day that she came home from the hospital was the day that

‘Closing Time’ was released as a single. The ambulance driver turned

back – I was with Coco and the nurse in the ambulance on the way home,

because she had a tracheostomy. The ambulance driver was driving us

home and at the stop light he turns around and says, ‘Are you Dan

Wilson?’ I said, yeah, I am. He said, ‘I just heard your band’s new

single on the radio. ‘Take me home, take me home, take me home.’’ I was

kind of blown away because I realized that the song is basically about

that situation – like taking someone home from the hospital.”

Of course, despite Wilson’s reality check, the music biz hype machine

rolled on, and being a good soldier, Wilson went along with it all.

However, looking back, he realizes that he became more grounded because

of his circumstances.

Of course, despite Wilson’s reality check, the music biz hype machine

rolled on, and being a good soldier, Wilson went along with it all.

However, looking back, he realizes that he became more grounded because

of his circumstances.

“As the song became more of a hit and the band is on MTV all the time

and we did all these crazy, silly, dancing bear moments in TV shows and

stuff like that, I was living a very different drama in my private life

that was so overwhelming that I didn’t really get swept up in [it.]

Yeah, I had kind of an ego trip, but it wasn’t as bad as it might have

been. I had a lot of distractions.”

“Closing Time” ended up becoming one of the biggest radio hits of the

year (and is still a radio staple), but “Secret Smile” did not quite

explode as much as expected. Their 2001 follow-up album All About

the Chemistry spawned a smash hit single in Europe called

“Chemistry,” but disappeared without a trace in his homeland. In the

meantime, Wilson was getting a reputation as a songwriter and producer –

working with the likes of Jewel and Bic Runga. He reached a turning

point yet again in his career and decided to move on from Semisonic.

In the years since Semisonic faded away, drummer Slichter has been very

open about his disappointment with the experience that Semisonic had

with MCA. In Slichter’s book So You Wanna Be A Rock and Roll Star

and in articles, Slichter has stated that payola is used to make a song

a hit and that it makes it nearly impossible for a band to ever pay

their debts to the label. While Wilson understands his friend’s

misgiving, he takes it a little more philosophically.

“I felt like I got waltzed down the aisle several times by MCA,” Wilson

says. “They tried their best. They had their problems as a record

promoting machine. However, looking at it through another perspective,

Semisonic was – if not the best thing they had, we were among the best

things they had. So they made the best with what they had and we, I

think, benefited from that. I don’t know how well we would have done if

we’d been on Geffen, which was one of the possibilities. Hole was on

Geffen and Nirvana. Things were on Geffen that were getting a lot of

attention and a lot of promotional push. I have to feeling that

Semisonic might not have actually had the opportunities we had.

“I think we found our match in MCA, strangely enough, even though I

think Jake is right. They had their serious drawbacks. When they

decided we weren’t going to be famous anymore, they really did kind of

decide that it was over for us, and that was a little bit annoying.

But, what are you going to do? The fact is they stopped promoting

Feeling Strangely Fine when they felt it had run out of steam

financially for them. That’s their job. They couldn’t stop ‘Closing

Time’ from being kind of a monument somewhere out on the landscape.

It’s not going away. Then, they couldn’t stop the UK company from

putting out ‘Secret Smile,’ which came out in the UK about a year after

‘Closing Time.’ And then

we had a huge hit over there with that. It was a hit in Europe. It was

a hit in England. We basically ran the whole game again. Okay, get in

a bus, travel around Europe and England and Ireland. I know Jake’s

perspective is correct about MCA and their sometimes weaknesses. But I

think we had a really good deal out of it.”

“I think we found our match in MCA, strangely enough, even though I

think Jake is right. They had their serious drawbacks. When they

decided we weren’t going to be famous anymore, they really did kind of

decide that it was over for us, and that was a little bit annoying.

But, what are you going to do? The fact is they stopped promoting

Feeling Strangely Fine when they felt it had run out of steam

financially for them. That’s their job. They couldn’t stop ‘Closing

Time’ from being kind of a monument somewhere out on the landscape.

It’s not going away. Then, they couldn’t stop the UK company from

putting out ‘Secret Smile,’ which came out in the UK about a year after

‘Closing Time.’ And then

we had a huge hit over there with that. It was a hit in Europe. It was

a hit in England. We basically ran the whole game again. Okay, get in

a bus, travel around Europe and England and Ireland. I know Jake’s

perspective is correct about MCA and their sometimes weaknesses. But I

think we had a really good deal out of it.”

Still, it was time to move on, and Wilson started working on his solo

debut, which would eventually become Free Life. However, life

had another sidetrack in store for him. It all started when Wilson

invited Sheryl Crow to sing on a few of his songs – including “Sugar,”

which made it onto the final album. Wilson sent her the rough mixes of

the songs and Crow loved how they was coming. She happened to see

super-producer Rick Rubin, who has worked with an eclectic group of

artists from Johnny Cash to Run DMC. Rubin asked Crow who she had been

listening to lately. Crow told him about Wilson and played the songs

for him. Rubin was so impressed that he signed Wilson to his label,

American Recordings.

At about the same time, Rubin was working on the latest album by country

supergroup The Dixie Chicks. The Chicks had been the biggest act in

Nashville up until 2003, when lead singer Natalie Maines made a

statement in a London concert against the war in Iraq that she was ashamed that George W. Bush was from Texas.

This led to a firestorm of controversy in the notoriously right-leaning

country music world and the band was pilloried for their beliefs. Their

songs were suddenly dropped from radio playlists, fans burned their CDs

and their concerts were boycotted.

Two years later, the Chicks were working on the album in which they

reacted to the controversy which had sprung up around them. Rubin

played the group some of Wilson’s songs – including ‘Sugar,’ ‘All Kinds’

and ‘Golden Girl.’ “They really, really related to ‘Sugar,’” Wilson

says. “They really thought that was a good song.” The Chicks told

Rubin that they wanted to write with Wilson for the album, which would

become the 2007 Grammy-winning best album Taking the Long Way.

Wilson ended up co-writing six songs for the album, including “Lullaby”

and the hit single “Not Ready to Make Nice,” which also took home a

Grammy for best song of the year.

“It was really exciting when they asked me to write with them,” Wilson

says. “I had seen them at a couple of festivals before all that bad

stuff happened. I had been completely blown away. They were amazing.

They were so fun. There were so virtuosic with their instruments and

singing. It was just really amazing. So I admired them and I actually

had a live album of theirs, so I knew a bunch of their songs. I was

really excited about working on the album, because I knew that they

didn’t have a choice but to address all that bullshit they’d gone

through. I knew that the songs were going to have to be really

substantial. It wasn’t going to be a fun record. It was going to be

something different. What I mean is it wasn’t going to be a record just

for fun and entertainment – it was going to be a personal statement.

When I got together to talk to them about it, that was exactly what they

wanted to do.

“It was really exciting when they asked me to write with them,” Wilson

says. “I had seen them at a couple of festivals before all that bad

stuff happened. I had been completely blown away. They were amazing.

They were so fun. There were so virtuosic with their instruments and

singing. It was just really amazing. So I admired them and I actually

had a live album of theirs, so I knew a bunch of their songs. I was

really excited about working on the album, because I knew that they

didn’t have a choice but to address all that bullshit they’d gone

through. I knew that the songs were going to have to be really

substantial. It wasn’t going to be a fun record. It was going to be

something different. What I mean is it wasn’t going to be a record just

for fun and entertainment – it was going to be a personal statement.

When I got together to talk to them about it, that was exactly what they

wanted to do.

“I warned them at the beginning – not warned them, but I said – you

know, I hate to say it, but I don’t think I’m any good at the kind of

third person story songs that you guys are famous for. You know,

‘Marianne and Wanda were the best of friends all through their high

school days…’ [from] ‘Goodbye, Earl.’ They had these stories that were

really awesome in some of their songs, for fictional characters. I

said, here’s the thing, I think I’m only really good at writing things

that are very much first person. It’s just about my life. They all

three said, ‘Well, good, that’s exactly what we’re trying to do here.’

We were definitely of the same mind and that was kind of a relief, but

also kind of thrilling to me to have that conversation.”

The collaboration bore fruit from the very beginning, with Wilson and

the Chicks coming together to write such beautiful songs as “Easy

Silence,” “Lullaby” and “The Long Way Around.” However, as much as he

was enjoying the work, there was still something missing.

“I really wanted to write the definitive song with them about the

political problems they’ve had,” Wilson says. “Where do you stand now?

What is your point of view, now? Where are we at two years later? I

felt like they hadn’t written it yet. I felt like you had to deal with

the elephant in the room. There was no pretending it didn’t exist. You

had to write a song about it. So I really pushed that. They wanted to

do it too. They just maybe hadn’t gotten the right combination of

things to happen.”

Then again, Wilson was also worried that “Not Ready to Make Nice” would

provoke another backlash and another big problem for the group. In

fact, as the CD was recorded, the song had a different title. Wilson

felt that it should be “Not Ready to Make Nice,” but he didn’t push the

issue, in fact he never even told them his feelings. However, when he

got the final song listing he found that the group had changed it to his

preferred title without him even discussing the possibility with them.

So he knew that the band was going forward unapologetically with the

song, which thrilled him and at the same time concerned him.

“I was excited but still kind of scared that they were just going to get

slapped again. Then I found out it was going to be the single.” Wilson

laughs. “So I got even more nervous about it. I really was rooting for

them to be able to stand up and have their say. Maybe [it was] just the

anxiety of hoping that I hadn’t steered it wrong to some degree – if I

had steered it at all – it’s obviously their record, their decision.

They are very, very clear on their vision of what they want to do. But

I guess I felt like I didn’t want to wave the flag for somebody that

would turn out to be another problem for them. Obviously, that’s not

how it turned out. It was a very nice redemption for them, I thought.”

“I was excited but still kind of scared that they were just going to get

slapped again. Then I found out it was going to be the single.” Wilson

laughs. “So I got even more nervous about it. I really was rooting for

them to be able to stand up and have their say. Maybe [it was] just the

anxiety of hoping that I hadn’t steered it wrong to some degree – if I

had steered it at all – it’s obviously their record, their decision.

They are very, very clear on their vision of what they want to do. But

I guess I felt like I didn’t want to wave the flag for somebody that

would turn out to be another problem for them. Obviously, that’s not

how it turned out. It was a very nice redemption for them, I thought.”

After helping the Dixie Chicks make their defining statement, Wilson

returned to making his own. Free Life had been partially done

for a while and it was time to finish it. In theory it should have been

a new experience for Wilson, the first time that he was recording

completely on his own. Not having to answer to bandmates or producers

or ever record company execs. He does allow, however that it wasn’t

that different to record an album while not a part of a band.

“My deal with Semisonic was that I was the leader of the band,” Wilson

said. “There was not going to be any voting. It’s not going to be a

democracy. I think they would tell you that I’m pretty good at leaving

enough space… we all get our crayons to color different parts of the

picture. But I’m usually going to do the rough outline. You can’t just

tell people what to do, because then they won’t do anything

interesting. Definitely, in that band it was always understood that the

last word would be mine if there was a conflict or whatever. The solo

record is different, because you don’t have the creative friction. You

don’t have the nominations of lots of different ideas coming up – and

being able to pick and choose. So I had to find a substitute for that.

One of the main substitutes for that was to invite a lot of people to

play and to really, really let them have a lot of leeway. In the

sessions I’d be relatively directive. I’d play things in a certain way

in guitar and piano, but I would let everyone stumble and crawl around

until it started to stand up on its own. I didn’t dictate very much.”

Amongst the great talents he worked with were Crow. “Sheryl was

extremely inspiring to work with. The minute she starts singing it

sounds more like a record. The minute she starts to do her thing it

loses all of its demo-ishness, you know? It suddenly sounds like

somebody’s album. It’s really interesting. She’s a very inspiring

collaborator. It was fun to have her… she sang on three songs, and I

recorded so many that the other two didn’t make the final cut. She sang

with me on, ‘Sugar’ and ‘Always Had a Feeling’ and there was one other,

‘Life.’ The other two are songs that haven’t been released.”

He

also has very impressive harmonies on the song “Against History” by Ruby

Amanfu, a lesser known but equally talented vocalist.

He

also has very impressive harmonies on the song “Against History” by Ruby

Amanfu, a lesser known but equally talented vocalist.

“She’s from Nashville and she’s unbelievable. She sang on ‘Against

History’ and she sang on ‘I Can’t Hold You,’ which is on the new EP.

She sang on a couple of other things, too. She sang on ‘Come Home,

Angel.’ And one other I’m forgetting.”

One thing that’s quickly noticeable on Free Life is that the

music is less overtly rockish than his earlier work in Semisonic.

Instead the album straddles styles and genres like folk, country and

pop. However, while Wilson acknowledges it has less of a rock edge than

earlier work, he doesn’t really work in a way that styles are dictated

beforehand.

“I don’t think I have as objective a view as that,” Wilson says. “I

don’t think that when I’m writing or working on a song I’m really aware

that it has a style. I just keep trying things until it sounds right.

It’s sort of only after the fact that somebody tells me that… like I

didn’t know that ‘Free Life’ sounds countryish. I can see that it does,

because of the pedal steel, but I wasn’t thinking that I want a

countryish version of the song. I just wanted it to be mournful. Pedal

steel has such a mournful sound, so I wanted to get the melancholy of

the lonely teenage afternoon listening to music. Pedal steel seemed to

me like an avenue to that. So, as far as experimenting with styles, I

don’t think I was doing that at all. It’s a valid way to describe it

and I think it’s a valid thing to do, if I were that kind of person. I

think it’s a perfectly good way to work, but I don’t think I have that

much self-awareness.

It all just comes naturally to

Wilson, because beyond just being a musician, he is a

fan and a student of music. He has an inquisitive and questing mind as

far as music theory. The day of our interview, I watched Wilson do his soundcheck for that night’s concert, and he played a seemingly random

group of other artists’ songs: “The End of the World” by Skeeter Davis,

“America” by Simon & Garfunkel and “The Rainbow Connection” from The Muppet

Movie. (He admits he has never heard Kermit

the Frog’s version of the

song. He had learned it from a Sarah McLachlan cover.)

When

I mentioned the songs to him later, he explained that it wasn’t a random

grouping. For some reason all three songs had been on his mind lately,

so he played them out to try to figure out why. When he did, he

realized that the three songs all had a common trait.

When

I mentioned the songs to him later, he explained that it wasn’t a random

grouping. For some reason all three songs had been on his mind lately,

so he played them out to try to figure out why. When he did, he

realized that the three songs all had a common trait.

“At soundcheck, when I played them, I realized they all do this one

series of moves,” Wilson explains. “Two/five/three/six major. It’s a

really strange set of chords, because that six major is out of the key.

That should be a minor, but it’s a major. Each of those songs does

that. The chorus: (sings) ‘Someday you’ll find it, the Rainbow

Connection.’ That goes to that weird six major chord. And ‘End of the

World’ : (sings again) ‘Don’t they know it’s the end of the

world?’ That ‘end of the world’ is the same weird chord as is in

‘Rainbow Connection.’ (resings both lines) And also, Paul Simon

does the same thing in ‘America.’ ‘So we bought a pack of cigarettes

and Mrs. Wagner pies.’ It’s the same little weird, brief change of keys

in each of those songs…. I’m certainly going to use that trick. It’s

such a great little emotional sounding change of keys.

“I’m not always perfect at it, but usually if I have five minutes I can

figure out most songs and play them. Yet, it’s only after I go through

the trouble of figuring it out and ‘What was he doing here? How did

that voicing work? What is the real bassline in that chord?’ It’s only

after I do all that stuff that I really feel like I can understand the

song and get inside it. Then I suppose I’m ready to steal their ideas,”

he smiles.

Well stealing may be a little harsh, let’s

call it gleaning inspiration. As an

artist, Wilson knows that it is only natural to draw ideas from other

artists’ work. For example, lately he has been completely taken with a

song called “Broken Afternoon” by a Portland, Oregon-based band called

The Helio Sequence.

“There always

seems to be somebody that I’m obsessively listening to,” Wilson

explains. “All the time. I think that’s been the story of my life.

I’ve always had some song that was haunting me. I once told a painter

friend of mine – when I was painting a lot – sometimes I think the

reason I make paintings is because I’ll see something in a museum and

I’ll go, oh, I want one of those. I think I’ll make one of those for

myself. My friend said, ‘Yeah, you’re in good company, because Picasso

once said that about Velàzquez.’ He would see something in a museum and

say, ‘I should make one of those myself.’ And it never comes out

looking like the model. It always comes out looking like the artist.

Same with me. I’m listening a lot to this Helio Sequence record and

loving it and I’m going to be trying to cop some idea from it, but it’s

always going to turn out sounding like me, you know?”

That’s okay. It’s

all about making your own masterpiece. Art is there to be appreciated.

As an artist, Wilson acknowledges that that is all you can hope for.

“What makes me happy is when someone writes me a letter and says, ‘We

used your song at our wedding,’” Wilson says. “Or ‘We used your song at

our friend’s memorial.’ What makes me happy is when someone tells me

they listened to Free Life on a road trip across America and it

was the soundtrack to the whole country. They went across the plains

and up the mountains and down the west coast, listening to Free Life.

That makes me really happy. I guess I want to be able to make music

that becomes part of people’s lives and becomes somehow embedded in

their personal experiences.”

Features

Return to the features page