You never know

where inspiration for a film will come from, but normally it does

not appear in the form of an FBI squad swooping into your wife’s

office to arrest one of her co-workers.

However, that was

exactly how filmmaker Marshall Curry and his co-director Sam Cullman

really came to learn about the Earth Liberation Front. The

co-worker was Daniel McGowan, a thirty-something New York native and

son of a policeman who joined in the group to protest

corporations that were destroying the

environment.

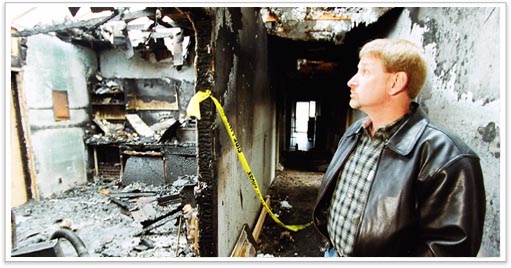

Eventually the

ELF became infamous when some of the more radical members convinced

other to take the law in their own hands and set afire

companies that were defiling the Earth. The fires became a pretty

big news story at the time, and yet the group still mostly flew

under the radar, up until the point that the law caught up with them.

“It’s surprising

to hear people’s reactions,” co-director Cullman admits. “Some

people had heard about them, but it seems like the majority of

people did not. As the number one domestic terror threat in the

United States, you’d think it would have more mass penetration.”

However, in the

eyes of the protestors, what they were doing wasn’t so much a

criminal act as it was a form of protest.

The product of

over four years of hard work, the documentary If a Tree Falls: A

Story of the Earth Liberation Front was released to critical

acclaim last summer. The film follows McGowan and other members of

the group, as well as members of law enforcement and some victims,

as they all negotiate the legal ramifications of the actions.

Now, months after

the film’s theatrical release, the filmmakers were recently happy to

learn that their film had been nominated for and Oscar for Best

Feature Documentary. “Yeah, it’s crazy news,” Cullman says

good-naturedly.

I was recently

able to sit down and speak with Curry and Cullman about their movie,

the Earth Liberation Front

and protest in America.

You

say early on in the film that Daniel McGowan was arrested at your

wife’s office. At that time, was she... or were you... familiar with the

Earth Liberation Front. Did

either of you know anything about Mr. McGowan’s

role in it?

You

say early on in the film that Daniel McGowan was arrested at your

wife’s office. At that time, was she... or were you... familiar with the

Earth Liberation Front. Did

either of you know anything about Mr. McGowan’s

role in it?

Marshall Curry:

We

knew very little about the Earth Liberation Front. I’m sure

we read

the newspaper stories when the huge arsons at Vail happened and some

things like that, but we had no idea that Daniel was a part of it.

When did you come

to think that the ELF was an interesting subject for a film?

Sam Cullman:

I

think pretty immediately. Daniel was a great entry point into the

story, but I think the intersection of issues – not just the ELF’s

history, but the consequences of their actions and their ultimate

arrests – just touch on so much that is at stake in

America. Questions of environmentalism and terrorism and activism

itself.

With some current

groups out there like the Occupy movement and even at a different

extreme the tea partiers, do you feel like the story of the ELF is a

cautionary tale?

Marshall Curry:

Yeah, it’s been very interesting to see the emergence of the Occupy

movement. When the film was first theatrically released last

summer, it was kind of a historical film. I think a lot of people

thought, “Oh, isn’t that quaint that there used to be a protest

movement in the United States.” When the Occupy activity started,

it was pretty remarkable to see history start to seem like it was

repeating itself – both with civil disobedience and some of these

actions happening and also with the police response, using pepper

spray on people. So, we do feel like the movie is a cautionary tale

for activists to think carefully about their tactics and the ethics

and the legal consequences and the effectiveness of different

tactics. Also, it’s a cautionary tale to the government to think

about how they react, because I think some reactions – like pepper

spraying people who are involved in non-violent civil disobedience –

radicalized people. It pushed them towards doing things like the

Earth Liberation Front, while other responses bring people into the

democratic argument.

Obviously many of

the occurrences in the film were big news stories long before you

got involved – particularly the Battle of Seattle. How many of

these things had you heard about or even followed before deciding to

make the film?

Marshall Curry:

We

knew about them. We follow the news pretty well and are

relatively politically aware. So we had some background. But,

definitely the process of making the movie took us into these

stories at a much deeper level.

I’m

not going to lie; I had kind of conflicting feelings about the

group. I do strongly believe in many of their causes and at the

same time I couldn’t help but think that they did eventually go over

the line with some of their ways of handling things. As filmmakers,

was it hard to stay impartial about everything as you were learning

about what happened?

I’m

not going to lie; I had kind of conflicting feelings about the

group. I do strongly believe in many of their causes and at the

same time I couldn’t help but think that they did eventually go over

the line with some of their ways of handling things. As filmmakers,

was it hard to stay impartial about everything as you were learning

about what happened?

Marshall Curry:

I

think it was less a question of impartiality and that sort of thing

as much as responding to the story that was presented to us.

Everywhere that we turned along the process of making this film –

talking to people involved in the arsons and the detectives and the

victims – people just sort of surprised us. When we first started

making this film, the general media environment discussing these

issues was really, really polarized. Cops as pigs and

environmentalists as wayward hippies and industry as gluttons – it

just seemed that things had gotten into such extremes that nobody

was really getting into nuance. Then when we talked to the actual

people involved, there really was a ton of nuance there. So we felt

compelled to reflect that complexity in the film itself.

Once you started

looking back at them in an almost investigative way and knowing some

of the people involved and some of their reasons, how did it change

your understanding of the events?

Sam Cullman:

Well, I think it just opened up a complexity. You can caricature

people when you don’t know them, but once you spend time with

somebody like Daniel McGowan, you start to understand. Which is not

the same thing as saying you agree with or you condone. But you

start to understand some of the things that led him to do these

fires. Similarly, once you spend time with the detective on the

case or the arson victims, you start to understand them as real

people, who, in the case of Steve Swanson, actually suffered as a

result of these fires. They were not victimless fires. So, I think

that getting to know the human side of this story, as opposed to the

purely political side of this story, gave us a much more nuanced and

much deeper understanding of the whole thing.

Daniel McGowan

certainly did not seem the type to become involved with something

like this. Were you rather shocked by how varied the people who

ended up being a part of the movement?

Sam Cullman:

Yeah, absolutely. One of the things that is true about this film is

that we call it “A Story of the Earth Liberation Front.” It’s “a

story” because there were 20 people caught up in this particular

group of arsons and people who were in this investigation.

Everyone’s stories and backgrounds were very different. That said,

there are some commonalities and I think Daniel’s story in some ways

speaks to some of that. This general frustration with the process

of making change and how slow change can be and how difficult change

can be. Then this point – which for everyone is different – at

which they turn and decide to cross the line and take on arson as a

means and a tactic to move forward.

The

film was made in conjunction with a lot of the court cases, and

several people that you were talking to were going in and out of

jail during that time. How did that complicate the making of the

movie?

The

film was made in conjunction with a lot of the court cases, and

several people that you were talking to were going in and out of

jail during that time. How did that complicate the making of the

movie?

Marshall Curry:

I think it raised the stakes a bit for people. There was a lot of

stress for people during that time. Getting access was probably the

most difficult part of the process. The activists, some of whom

were facing life in prison, were reluctant to talk to somebody who

they didn’t know. They were afraid that we would do what the media

always did, which is caricature them as hippie terrorists. I think

that the prosecutor and the arson victims also were a little

reluctant to talk to us. They had cases that were going on and were

worried that maybe we would edit what they said out of context.

That we had some environmentalist agenda and we would try to make

them look bad. So we had to spend a lot of time explaining to

people that we were really interested in their points of view and

that we wanted the movie to show people’s best arguments banging

against each other, rather than setting up straw men and knocking

them down.

Were there any

people involved who you could not get access to or only get less

than you would have liked? For example, while you did speak with

Jake Ferguson, for a long part of the movie he was just a shadowy

figure and I was a bit surprised there was not more footage of him

speaking out about his role in the events.

Marshall Curry:

Actually, it’s funny that you mentioned him. He was someone that we

spent a lot of time trying to get access to. I was able to get his

lawyer to agree that he should talk to us. At one point, we had a

conversation set up and then he sort of flaked on it. Ultimately,

he did an interview with some folks in a TV station and the result

of that was really negative in the activist community, so he decided

he wasn’t going to do any more interviews after that. We actually

were not able to get an interview with him. The footage that you

see in the movie are outtakes from another interview that he had

done. Fortunately the interview was the same basic questions that

we would have been asking him. But that was one that we weren’t

able to get.

Not speaking as a

filmmaker, but just as a citizen now, in a country where a large

percentage of the population refuses to even see that the state of

ecology as a problem, do you feel that sometimes extreme measures

are necessary?

Sam Cullman:

I think that’s definitely a central question in our film. To speak

as citizens versus filmmakers, I don’t know. But I do know that I

do think that we need to be confronting these issues. If

there is a moral out of this in particular:

arson is probably not a very effective way of getting your point

across. With the experience of the ELF, it may have gotten

into our consciousness – which I think is something that they wanted

– but certainly, it also had a lot of negative

repercussions. Not just for the people who were victims, but also

for the movement itself. You look at movements today, whether they

are based around issues like climate change or otherwise, it has to

be about coalition building and it has to be about bringing people

into a movement. When things are born out of frustration or born

out of a very small group, the chances of affecting change is very

difficult. So, I do think that the lessons of the story are ones

that we can draw from.

With

the political climate more divided today than it has been perhaps in

any time in American history, do you think that it is even possible

to change people’s minds on what happened, or will people just go in

with preconceived notions and seize on the points that support their

views?

With

the political climate more divided today than it has been perhaps in

any time in American history, do you think that it is even possible

to change people’s minds on what happened, or will people just go in

with preconceived notions and seize on the points that support their

views?

Sam Cullman:

Look at Occupy, right? The conversation has shifted because of what

they did and what they brought to the table in just four months in

the United States. There’s many ways of injecting your voice into a

public debate. It is not impossible. It’s difficult, but it’s not

impossible.

In a lot of ways,

the Occupy protestors were an outshoot of earlier hippie protests,

not completely, but mostly peaceful. Is it possible to just have a

peaceful protest at this juncture in history and make that kind of a

difference?

Marshall Curry:

Yeah, I feel like the Occupy movement is a sterling example of

that. I saw an article recently that was analyzing the number of

times that The New York Times used the words “income

disparity” in the year before the Occupy movement and since. It was

something like a 10,000% increase. I’m sure that if you analyzed

the number of speeches on Capitol Hill and the number of times that

this idea now has become a mainstream point for people to consider –

that is a direct result of non-violent civil disobedience.

One of the great

ironies of the group – and of course the movie – was that the people

who stayed most faithful to the ideals of the group were punished

the most, while other members who may have been more involved in the

criminal protests were able to get off easier by informing on their

fellow members. Did it surprise you that some of the most active

members of ELF seemed to jettison their beliefs when it became

obvious that it was in their self-interest to do so?

Sam Cullman:

Yeah,

I think it was, among other tragedies, a certain piece of

tragedy in this story, to hear that this group that had had

passionate solidarity ultimately betrayed each other, many of them,

along the way. But it’s not surprising that these things happen.

If we look at the federal incarceration numbers, something like 90%

of people end up pleaing out. Only very small fractions end up

going to trial, because power is very often in the hands of the

prosecution. I think that maybe their choices were as much of a

reflection of that as anything else.

A great deal of

the debate on the ELF which was discussed in the film is whether or

not the Front was a terrorist group or if it was just a protest

group. Obviously, as documentarians you can’t really choose sides,

but just as concerned citizens do you feel that Daniel McGowan and

some of his cohorts got a raw deal or do you think what they did

might have come within the definition of “terrorism?”

Marshall Curry:

We see it as a somewhat complicated issue. The folks whose

businesses were burned – they were certainly terrorized. They got

alarm systems for their homes. They didn’t know if their homes were

going to be attacked, if their car was going to burst into flames

when they got into it. So, if your definition of terrorism is

“somebody who uses intimidation to force you to do something or not

do something,” then there is an argument that these fires would

qualify. Now, the folks who are more supportive or sympathetic of

the ELF point out that no one has ever been harmed in any of these

arsons. These things are more like the Boston Tea Party.

They are symbolic property destruction and shouldn’t qualify at

all. I would say in the end, probably Sam and I are closest to the

police captain who says in the film that one person’s terrorist is

another person’s freedom fighter and he’d rather just focus on crime

and not crime. If you commit an arson, that is a crime and the

government should try to catch you and put you in jail and stop

people from committing arson. Whether it is terrorism or not is

maybe not even a helpful question. Terrorism might be one of those

words that creates more heat than light. It excites people and

generates a lot of emotion, but without clarifying what it is that

we are talking about.

Sam Cullman:

I think that it is sort of instructive for sure to know that the

federal government has differing definitions of what terrorism is,

even within itself in the United States. You look at a body like

the UN that has been struggling to define this for decades, with no

results. I think the reason for that is quite clear. The message

is that this is a potentially very subjective term that can be

wielded to differentiate positions of who is in power and who is at

the other end of power. I think there is a danger in that.

How did you find

out that you were nominated for an Oscar and what was that

experience like? Was it gratifying to see your hard work honored in

such a way?

Marshall Curry:

Sure. I mean it’s a huge thrill. I’ve got two kids, a five year

old and a seven year old. I was in the kindergarten class helping

my son hang up his jacket when my cell phone in my pocket started to

ring. That’s how I got the news.

Sam Cullman:

I was the Sundance Film Festival, showing a different film that I

had produced and shot. Getting the news out there was especially

thrilling, absolutely.

What do you have

coming next?

Marshall Curry:

I have a film that I’ve started shooting about Lennox Lewis, the

former heavyweight boxing champion. He retired about six years

ago. Now he’s 47 or so and he’s got 40 more years of living and is

trying to figure out what to do. When you’ve worked your whole life

to achieve something and you’ve achieved it, how do you make sense

of it? What do you do for your next chapter?

Sam Cullman:

I’ve been shooting a film for the last few months about an art

forger in the United States – someone who has been forging art for

30 years and donating it to museums and institutions and has just

recently been caught.

Email

us Let us know what you

think.