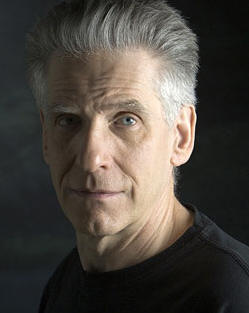

DAVID CRONENBERG

DAVID CRONENBERG

A DIRECTOR LOOKS AT VIOLENT AMERICA

by Brad Balfour

Copyright ©2005 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

November

3, 2005.

Now transformed from a

horror genre master (Rabid, The Brood, Scanners, Videodrome) to a

full-blown, critically acclaimed and analyzed auteur, Toronto-based

director David Cronenberg finally has made A History of Violence Ė

the film that may be the Oscar-garnering capper of his career. With

Cronenberg having done films with exploding heads, weird parasites

entering various body parts, and babies growing in sacs on their mother's

stomach, this story of a simple small town cafe owner confronted with a

criminal act that makes him a hero and changes his life, is downright

restrained beyond belief. Yet the 62 year-old Cronenberg has crafted a

timely meditation on the nature and effect of violence on a man and his

family.

What did you really want this film to address?

The iconic American

mythology was very interesting to me. I haven't set a movie in America

since The Dead Zone. It's not like I have a message to the world.

When it came to the depiction of violence, it was where did the characters

learn their violence? And what was violence to those characters, but my

idea of what I think violence should be. Violence is innate in humans; we

are that strange creature that can form abstract concepts, so we can

conceive of non-violence. There are people who think that a world full of

peace would be boring and would lead to a loss of creativity. That's an

interesting, perverse argument that might some truth in it.

It's in this film.

The fact that the

audience finds the violence exhilarating and that the children find it

attractive, even though they are repelled by the consequences, shows the

conundrum we have with violence. So many people fear it, there's so much

money, energy, and government that are trying to avoid it at the same time

that we outfit armies to go and commit it on other people Ė itís very

paradoxical and endlessly fascinating, yet it's also very attractive which

brings out the animal part of ourselves. Even the human, intellectual part

of ourselves is also attracted to it. It's not easy to lament that we are

violent creatures because that is just too simplistic.

Even in the sex between Viggo Mortensen and Maria Bello?

That's right. People

experienced in sex and honesty will admit that there's a component of

violence in sexuality Ė whether it's subliminal or not. Radical feminists

have said that any form of sex is rape. I know that they are extreme, but

I know what they're saying and there's some truth in it. Even that which

can be considered tender and intimate is, in a sense, a spatial violation.

That's what makes human sexuality so complex and reflective of every

aspect of the human condition. That's why I tend to have sex scenes in my

movie; I am failing to really deliver the goods to myself and my audience

in terms of looking everywhere for what's really going on unless sexuality

is in some way being examined. Especially in this movie, where there's a

couple who have been married for 20 years and has two children and the

only sex scenes are between the couple. How could you really say you've

done your scenes-from-a-marriage routine if you haven't acknowledged their

sexuality in a very specific way.

Yet there's an optimism to this film.

The feeling is that, perhaps, for Edie (Bello),

the Tom/Joey (Mortenson) hybrid is the full guy. Perhaps the marriage

could even be a better marriage with the acknowledgment of that. Whether

she can live with that or not is a whole other thing. With the sex scene

on the stairs, there's an attraction-repulsion thing happening. That's

another reason why I felt I had to have that scene. Despite the difficulty

that people have with that scene, it is necessary to set up the

possibility of hope in the ending.

How

did you make your casting choices?

How

did you make your casting choices?

I gradually narrowed it

down. After all, the movie cost $32 million, which means I had to have an

actor of a certain stature for the studio to feel that they can sell the

movie. It's very straightforward. I didn't need a big star like Tom

Cruise, but I did need somebody who is recognizable and has fans already.

Very few movies can be successful with unknown actors. Even for a two

million dollar movie, the producers will want a recognizable name. That

automatically limits you to a certain number of people. Then there's the

age that the characters must be, within a certain range. And he has to be

somebody who can carry a movie as the leading man, but, for me, he has to

be more of a character actor. He has to disappear into his role as well as

be subtle, eccentric, charismatic, and real all at the same time. It's a

difficult thing to find. There's the subtle other thing that is beyond

articulation which is my sensibility in terms of actors. There are some

actors who I can admire in terms of their acting ability and stardom, but

no compulsion to work with them. I go for certain actors that are my kind

of actors.

What about an actress like Maria Bello?

The same goes for

actresses. Maria is a beautiful woman, but still not what somebody says is

the "ice princess" model of Hollywood

these days; she's real. That means that she bring subtlety, complexity,

and possibly the difficulty of her character. I want a real woman, but not

an icon.

You've never been afraid to show the ugliness of violence.

I don't know, I must be

fearless, it seems. For me the first fact of human existence is the human

body. I'm not an atheist, but for me to turn away from any aspect of the

human body to me is a philosophical betrayal. And there's a lot of art and

religion whose whole purpose is to turn away from the human body. I feel

in my art that my mandate is to not do that. So whether itís beautiful

things Ė the sexuality part, or the violent part or the gooey part Ė itís

just body fluids. It's when Elliott in Dead Ringer says, "Why are

there no beauty contests for the insides of bodies?" It's a thought that

disturbs me. How can we be disgusted by our own bodies? That really

doesn't make any human sense. It makes some animal sense but it doesn't

make human sense so I'm always discussing that in my movies and in this

movie in particular. I don't ever feel that I've been exploitive in a

crude, vulgar way, or just doing it to get attention. It's always got a

purpose which I can be very articulate about. In this movie, we've got an

audience that's definitely going to applaud these acts of violence and

they do because it's set up that these acts are justifiable and almost

heroic at times. But I'm saying, "Okay, if you can applaud that, can you

applaud this?" because this is the result of that gunshot in the head.

It's not nice. And even if the violence is justifiable, the consequences

of the violence are exactly the same. The body does not know what was the

morality of that act. So I'm asking the audience to see if they can

contain the whole experience of this violent act instead of just the

heroic/dramatic one. I'm saying "Here's the really nasty effects on these

nasty guys but still, the effects are very nasty." And that's the paradox

and conundrum.

You're a Canadian who's made this essay about violence in America and you choose not to adorn it with special effects and visual

dramatics; that makes this story so profound and so "Cronenberg..."

Yeah, it's a tendency I

have and I relate it somewhat weirdly to Samuel Beckett, and modernism.

Somehow I feel that to me, one of the ultimate challenges is to not adorn,

not to hide behind stuff. There are very easy things that you can do in

films, especially now, to disguise yourself and make things easy and

protect yourself. I'm as vulnerable as my actors, maybe more so when I

direct a movie. Maybe not in the same physical way, but very vulnerable

and itís very tempting to do stuff, to hide behind it. I try not to do it,

or get overly technique-y. If you can do it right, there's a raw

simplicity that's incredibly powerful because there's a certain truth

right there. If you blow it, there's nothing to hide behind. Itís obvious

when you've blown it. So that's why you get guys that do jittery camera

stuff when it's just a guy sitting in a room talking; they do stuff up

here and they've got cranes and whatever. I just sit there and say "Ok,

I've cast this guy for his face, for his voice, for his acting. I just

want you to see that. Let's just trust all that you've done and look at

this guy talking." I don't need to do fancy, silly stuff that has no

meaning or artistic purpose.

When

Tom/Joey leaves small town life, is he really changed?

When

Tom/Joey leaves small town life, is he really changed?

That's certainly the way

we played it. Imagine, he's suddenly forced out of the identity he had and

you have to decide how much of this you want to reveal to your viewers

obviously, or you could spoil the movie for them.

Don't worry.

[When he originally left

the East Coast], he could have chosen to be anything Ė to be a Joey in

Florida, or a Joey in the west coast. He could have gone to some other

country and been a small time gangster. But he chooses to be part of this

American mythology of itself, this kind of ideal guy in this ideal small

town with a family. Non-violent. Very sweet. Very gentle with his

children. And he genuinely is. He's been that for twenty years. So he's

been very successful at that. And that's not hiding. At that point he

really wanted to become somebody else. If he got hit by a bus before the

bad guys came to town, he would have been buried as Tom Stall, everybody

would have thought that's who he was and that's who he would have been.

So when the violence breaks out, was he reverting?

No. The way we were

playing it was that Joey was not actually a violent person. He didn't have

that incredible anger and rage. Because you would feel that if he had that

incredibly violent temper and anger and rage for example that it would

come out in those twenty years that he tried to be Tom. You know it would

have come out sooner. But in this case, Joey learned violence because Ė

being physically kind of athletic Ė he could be good at it, because he

grew up in the streets of Philly. His brother was a mobster, the union was

mobsters and to be successful and have some kind of life there, he had to

become part of that. He could do violence, so he did violence, but he

wasn't particularly innately a violent person. So it was just as he says,

when his brother says, "We're brothers, what did you think would happen?"

He replies, "I thought that business would come first." For him it was

business. And that was the approach to violence in the movie that I took,

which is rather an imposing concept of what violence should or shouldn't

be. I wasn't thinking about that... I'm thinking, "Okay in this movie

where does the violence come from?" It comes from these guys who learned

it on the streets and from the business. Its not sadistic pleasure, an

aesthetic thing, or a martial art with a philosophy in fighting, it's just

business. You do it. You get it over and get on to the next thing and make

as little fuss about it as possible. That's what it is to Joey, and

therefore itís very possible for it to disappear. Now it comes back only

because it's a tool he needs, that he has. It is like the gunslinger that

was the fastest gun in the west that put his guns away, you know? It has

American iconic reverberations and we were very conscious of that.

[Joey's] the guy who's reluctant to kill although he has a talent for

killing, but itís not something that gives him pleasure. That's really the

approach we took and itís realistic in the sense that it would make it

possible for him to become Tom and live that life for so long without

revealing something else.

When you show the sex scene after the shootings, the intoxicating effect

of the violence affects how they have sex with each other Ė as opposed to

before it was revealed.

If you see the movie a

second time, it becomes a different movie and only then can you really

appreciate Viggo's performance fully because we were conscious of making

two movies at once and it had to work both ways Ė for both viewings. But

once the violence cat is out of the bag itís up for grabs. For me the most

violent moment of the movie is when he slaps his son. That's a shocking

moment and you definitely get the feeling that it's the first time he ever

laid a hand on either of his kids violently. It depresses and shocks him

as well as shocking his son because the violence cat is out of the bag and

itís hard to put it back in. Once again it's a tool, but it's a tool that

has to be ready, the adrenaline has to be there, so and it comes out in

the sexuality as well.

Your

films have a weird air to them because they're like American but not.

Your

films have a weird air to them because they're like American but not.

Many years ago, a

producer who just started talking to me about that said, "You know, for

Americans, your movies are really weird." Now this was a long time ago,

because the streets are like America,

but they're not. The people are like Americans but they're not. It's like

the pod people kind of thing. And he said that gave [my films] that spooky

edge for an American. I'm thinking, "Well that's us Canadians, you know,

we're the American pod people. We're like American people but we're not,

we're quite different." I've only really set a couple of movies, maybe

three in America. One was The Dead Zone; another one, Fast

Company had scenes that were set in America.

You've shot in America?

I have never shot a foot

of film in America.

You didn't shoot the exteriors of the town in America?

That was Millbrook,

Ontario.

You can't compare Toronto to any American city, but itís all American cities in a sense.

Sure, it is, and there

are certain essences of American cities that are totally not there. It's

because our histories are interlinked but they're quite different. You

know, we didn't have a Civil War, we didn't have a revolution, etc. We

sent the mounted police into the western territories first with guns. Then

the citizens came without guns. So there was never that sense of intense

individualism that you have in America. Where a man with a gun, he's the

law, we always have had in Canada, more intense understanding of the

social fabric where you have to negotiate and discuss and stuff like that.

Is the virus in

History of Violence the past or is it violence itself the virus?

Well, you see, I don't

think that way, you know, in the sense that you're bringing a concept, a

sort of critical and analytical concept to bear on this movie. I

absolutely don't mind that, some very interesting and enlightening things

can come out of that process. But that's not a creative process, that's an

analytical and critical process; I don't think of that, for instance when

I was making the movie that thought would never have been in my mind.

There were many thoughts in my mind but I don't think about my other

movies. I don't think about the place of this movie in the pantheon and

blah, blah. I really take each movie on its own and try to give it what it

needs individually without imposing something from the outside, including

what people have thought about my other movies. So you're going to have to

answer that question I'm sure.

Reflecting

on your own life and on your own work, do you find that your movies are

like different chapters from the same book?

Reflecting

on your own life and on your own work, do you find that your movies are

like different chapters from the same book?

Yes, I don't deny

obviously that there is a connection. The thing is that I don't have to

force the connection, because you literally make one or two thousand

decisions a day as a director. There are decisions about everything from

clothes to colors, to walls, to locations to actors and what wins in

lighting and you'll know that nobody else would make those same decisions.

And so the movie will be enough of you, you don't have to force it. I

don't have to say I have to put this thumbprint on it so the people will

know itís my movie. Did I answer the question?

Well, how does this chapter in the book relate to your work?

But see, I don't have a

perspective on it because I've just made the movie. Itís my most recent

movie so I'm most involved with it and my other movies are the past and

I'm just not thinking of them. It's a legitimate metaphor that you're

using, that each movie is a kind of a chapter. I wouldn't have made this

movie the same way 10 years ago. I wouldn't have been the same person, so

it is revealing of something but I am the last person to be able to say

what that something is.

After the heaviness of Spider is it nice to kick some people in the face?

No, not at all. Although

I won't say that didn't have a reaction on Spider. But the reaction

was that I didn't make any money on Spider and I needed to do a

movie that I could make some money on. In the sense that I couldn't afford

to do a low budget independent film whose financing was constantly falling

apart and therefore we would all have to defer our salaries and not get

paid. I literally did not make any money for two years and I could not

afford to do that. So that was the reaction. On the other hand, Spider

was still a wonderful experience and frankly I think it's the other half

of this movie. I mean, it also is about identity and the construction of

it, and the possibility of it, and the consequences of it. In Spider

you have a man who does not have the will, the creative will for whatever

reason, to hold his identity together. He keeps disintegrating and falls

apart. But each movie has a family in it. Has a past that has a huge

impact on the present and its also, both movies are about identity. So I

think they would be pretty interesting on a double bill for a certain very

special audience.

Do you find it easier to work with an adapted screenplay?

It comes from laziness

and momentum, basically. Even Brian DePalma, who wrote his original

screenplays, took a while to finish writing them. You have to sit down for

maybe two years to write it. Maybe it's no good or maybe its okay but you

can't get it made. So, the pressure is on you to go with a project that a

producer has already been excited about so that you don't have to take

those two years off only to find that you haven't managed to produce

something that's worth making. When I did The Dead Zone, my first

adaptation, I found it exciting to get out of myself. You can bore

yourself with you. The idea that you will fuse with some other

interesting, different personality and then create some third thing that

neither one of you would have produced on your own is really interesting.

I did that with interesting people like Stephen King, William Burroughs,

J.G. Ballard, and now Josh Olson.

With A

History of Violence, has your filmmaking style changed?

I don't know if it

changed. I'm always experimenting, which comes from the nature of the

particular project. Each movie demands its own things, like a child. It

starts to become something else. As the doting parents, I feed it what it

needs so that it evolves into its own individuality. The movie tells me

what it wants, which could be different from what cinema should be or from

what my movies used to be; I can't think about all that stuff---I can only

think about feeding this demanding child.

Do

you think

Spider and A History of Violence share some thematic elements?

Do

you think

Spider and A History of Violence share some thematic elements?

I only see that after

the fact. It's not like I thought of that when I started to make this

movie. It's only when I'm doing interviews and people are asking me to be

analytical about my films. The creative impulses are different from the

critical and analytical ones.

Why do people who make comedies tend to be angry and depressed and

people who make very violent movies tend to be nice and funny?

It seems to be true,

isn't it? I mean there's nothing scarier than a comedian. They're angry,

depressed, terrible people. Let's face it. It must be. I mean I guess itís

easy to say, but it seems to be inevitably true that there's a kind of

balance that's struck. If you're kind of perky and funny in your life then

you feel that you have to deal with the other stuff in your art and vice

versa, you know.

Are you excited about the buzz about this film Ė given that you're a

Canadian making such an American film?

I've been through this

before [laughs]. With Dead Ringers, I was told endlessly

that Jeremy Irons was a shoe-in for best actor at the very least, but, of

course, that didn't happen. So, I realized the game-playing that goes on.

Although, The Fly did win an Oscar for best special-effects and

makeup, so I have done the Oscar thing. But it's not a goal and it's not a

necessity.

What are you working on for the future?

There are a few projects

that are possible. One is an adaptation of

London Fields

Ė Martin Amis'

novel; I'm a huge Martin Amis fan. Another is called Maps to the Stars,

which is written by Bruce Wagner who is also an LA novelist and a close

friend. Robert Lantos will be producing that if that happens. There are

all things that are possible, but they are not at all for sure. They would

be in the independent film range of budget and financing.