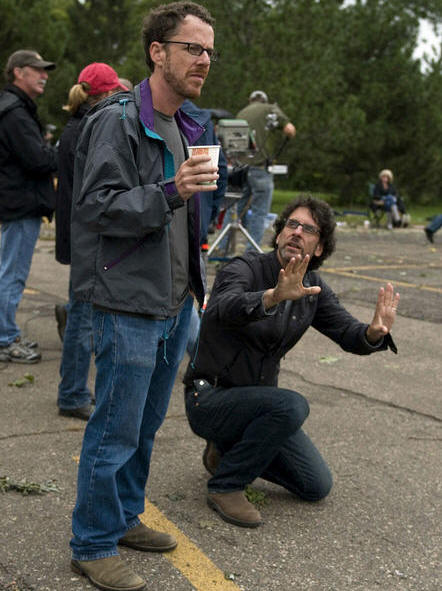

Brothers and

auteurs Joel and Ethan Coen grew up in a sparse, ticky-tack,

rustic early suburb of Minneapolis in the late 60s.

Now, after

over two decades in filmmaking in which they have turned their

incisive pens (okay, more likely computers) onto areas such as North

Dakota (Fargo), Texas (No Country for Old Men),

Hollywood (Barton Fink) and Washington (Burn After Reading),

the Coens have finally made a film based upon their own home ground.

The Coens

insist that A Serious Man is not an autobiographical piece,

however it is obvious that they know the world of suburban Minnesota

Judaism in the late 60s. Their obvious love and occasional disdain

for that universe fuels this small but

intimately funny film.

Fittingly for

such a personal film, the Coens have downsized, using a mostly

unknown cast to populate this world of mystical rabbis, intellectual

theorems, the Jefferson Airplane, gambling, tenure, record clubs,

the new freedoms and cosmic uncertainty.

Starring

Broadway vet Michael Stuhlbarg

in a breakout performance as Larry Gopnik, a science

professor who has suddenly been hit by life with a never-ending

series of indignities and problems.

Soon before

the films’ release date, the Coen Brothers met up with a small group

of journalists in New York to discuss their latest work. The

brothers spoke casually and passionately together about this obvious

labor of love – periodically interrupting and talking over each

other in an organic way of people who have been speaking together

for all their lives. Joel even joked that

any point either one made could be attributed to the other if it was

unsure who was talking at any given point – it really didn’t matter

who said what, most facts were agreed upon.

I’m

going to try to get the Jewish issues resolved. I saw a lot of

cultural Judiasm in the movie – growing up Jewish. You also had a

lot of authentic religious Judiasm in the movie. How much of that

was from your educational experience and how much did you have to

research?

I’m

going to try to get the Jewish issues resolved. I saw a lot of

cultural Judiasm in the movie – growing up Jewish. You also had a

lot of authentic religious Judiasm in the movie. How much of that

was from your educational experience and how much did you have to

research?

Ethan Coen:

We didn’t do any research, per se. Once the script was written, when

we actually started making the movie, there were a couple of people

who kind of were our Jew advisors – Jew technical advisers –

helping us just with language and the liturgical stuff for the

service and whatever. Of course, we got a raft of translators for

the Yiddish beginning of the movie. A raft of dueling Yiddishists.

Everyone had an opinion about what form of Yiddish we should use.

Joel Coen:

We actually did have one problem we brought to a fluent

Hebrew-speaker. We had a specific problem – wanting to have a Hebrew

expression for the translation of “Help me” that was exactly seven

letters long. We wanted it to be a phone number.

Ethan Coen:

The main technical guy was this Cantor – and now a Rabbi as well,

named Dan Sklar.

Joel Coen:

He gave us a good suggestion.

What were your

Bar Mitzvahs like?

Joel Coen:

What were

they like?

Do you remember

the passage you had to read?

Joel Coen:

No, I don’t.

Ethan Coen:

No. (laughs)

Did you help each

other? Did you read the whole portion, or you read just one Torah?

Joel Coen:

No, we read the whole Torah.

Ethan Coen:

I didn’t read all the Torah portions. Just one or two.

Joel Coen:

It was pretty typical conservative congregation bar mitzvah circa

1967. I don’t know what they are doing now, to be honest with you.

Out there – I mean I’ve been to a few in New York. (laughs)

They’re not intricate, you know. There wasn’t anything out of the

ordinary, to be quite honest with you. I wish I could tell you

something more interesting than that, but that’s the truth.

Did

you feel a competition with the other kids about who got more

presents?

Did

you feel a competition with the other kids about who got more

presents?

Ethan Coen:

Oh yeah, you and your peers compare what the haul was.

And did you do

that with each other?

Joel Coen:

Well there was the three years difference so not so much.

Ethan Coen:

As in the movie, we each got a Kiddush cup that was a gift of the

Sisterhood.

Do you still have

them?

Ethan Coen:

Joel still has his. I don't have mine.

What was your

inspiration in doing this film?

Joel Coen:

Well, it’s always really hard to say. Personally we don’t really

know. The truth of it is you start to think back on it and you

impose more order and rationality on it than actually occurred when

you were thinking it out. I think we were just thinking about… we

had an idea long ago that maybe we would do something. We were

thinking about short films years ago and there was a particular

rabbi in our town – not our rabbi – who used to meet the kids after

the bar mitzvah. He was sort of a sphinx-like, Wizard of Oz

kind of character. We thought that might make a good short years and

years ago. Somehow that idea finally became this story. We started

thinking about doing something set in 1967 in that community,

because that was such an interesting point in our own childhood.

Part of it came from thinking about the music from that period – the

combination of music. Jewish liturgical music and cantorial music

and the Jefferson Airplane – just a bunch of different things.

Out of all the

songs of the period, why "Somebody to Love?"

Ethan Coen:

Oh, it could have been any of a number of songs, I guess. We just

kind of focused on that early, lit on that early, because it's so

much of that time. That time really specifically, not even just 60s,

but ‘67. Spring of ‘67. Surrealistic Pillow. It’s so much of

that. It smacks of the time. Also, we used the lyrics. They pay off

in the end in a way that it became clear to us that they would be

useful.

Were you big

Jefferson Airplane fans?

Joel Coen:

Not particularly. I mean, we listened to them. I’m not saying we

were big Jefferson Airplane fans, though.

Ethan Coen:

But, obviously, they were big. There was also – just a thing about

the synagogue. Actually, the rabbi’s rap at the end at the Kiddush

cup was almost verbatim from…

Joel Coen:

… from our bar mitzvahs…

Ethan Coen:

Yeah. The guy had the same thing every Saturday.

Michael

Stuhlbarg is mostly unknown in film. Why did you feel he was right

for the role?

Michael

Stuhlbarg is mostly unknown in film. Why did you feel he was right

for the role?

Ethan Coen:

Joel knew him slightly. We had both seen him in a few plays. But you

know him from the project, right?

Joel Coen:

I knew him from stuff he’s done in theater. Some of the stuff he’s

done in New York. He’s done a lot. And from the 52nd Street

Project.

Are you involved

in that?

Joel Coen:

Well, I’m not, but my wife has been involved with it for seven

years.

They go up to

your place in the country?

Joel Coen:

Yeah. You know about that?

I did interview

Michael before.

Joel Coen:

All right.

You used a lot of

local actors. How do you think that added to the movie?

Ethan Coen:

We knew we really wanted it to be about Midwestern Jews. It's a

different community. It's a different thing than New York Jews, LA

Jews. It’s just different, the whole Midwestern thing. It isn't just

about a Jewish community. The geographic thing is kind of specific,

so that was important to us.

Joel Coen:

That area happens to be a place where… it’s not true everywhere… but

you can find lots of very, very good local actors there. There is a

big advantage to it. There's a practical reason as well as an

aesthetic reason.

Ethan Coen:

Yeah, they are all really [talented]. It’s a largely local cast,

Sari Lennock, who played the wife, she was great. She lives there.

Ari Hoptman, who plays the head of the department – is very much

Minnesota. All the kids were local.

You see Larry’s

neighbor hunting with his son. In

No Country for Old Men, Josh Brolin goes hunting in the

beginning of the film. Is that a coincidence or you guys into

hunting?

Joel Coen:

No, it’s just… Josh hunting the antelope in the beginning of No

Country for Old Men – we didn’t write that. That’s in the book.

Ethan Coen:

The next door neighbor is just hunting as a goyish activity.

Much

of the film seems to be contrasting this Jewish neighborhood with

the cultural shift of the 60s. What did you feel was important to

say about that shift, particularly in the Midwest?

Much

of the film seems to be contrasting this Jewish neighborhood with

the cultural shift of the 60s. What did you feel was important to

say about that shift, particularly in the Midwest?

Joel Coen:

In the community we lived in, the Jewish community was centered in

part of the downtown area for many years. It sort of shifted out to

the suburbs. It wasn’t that there Jewish communities in the suburbs,

it became less Jewish. It was these new developments which were

populated by Jews. It's also a mistake to say that the Jews were in

any way a majority of even that community. We grew up in a community

that was predominantly not Jewish. It's just that the Jews were a

big and significant section of it. The community itself was a

direct, correlated, cohesive thing. You felt like the Jewish

community was part of what was your experience. And yeah, you’re

right. There was that idea of the post-war thing, where the

populations in terms of minorities in cities were shifting, and

culturally things were shifting. I don't think we thought a lot

about it, but we liked that period generally for that reason.

Sort of like

Levittown (an early suburb in New York)?

Joel Coen:

I guess a

little bit. There were big developments that were being put up that

were suburban tracts, which were [on a] drained swamp or prairie. It

was kind of like that.

Ethan Coen:

It was a little bit post-Levittown, but the same thing, yeah.

You start the

movie with a quote from Rashi. Really nobody uses quotes from Rashi,

he’s not that kind of guy. How did you come across the quote?

Joel Coen:

(laughs)

I can’t remember where I first saw that.

Any more theater

coming up for you? I loved your one-acts.

Ethan Coen:

Yeah,

maybe. I don’t know. Yes, hopefully, but nothing definite.

You

guys portray the Hebrew school experience as torture. Anything from

your Hebrew school that you were engaged by?

You

guys portray the Hebrew school experience as torture. Anything from

your Hebrew school that you were engaged by?

Ethan Coen:

I left Hebrew school just once and that’s it for us. You go there

after secular school.

Joel Coen:

Those were two hours that you desperately tried to get out of for

many years and years and years.

Is there a

connection between this and the fact that you are doing

The Yiddish Policemen’s Union (based on the Michael

Chabon novel)?

Ethan Coen:

No, that’s kind of a coincidence, too. The producer, Scott Rudin,

acquired that novel and then just hired us to write the script. I

guess we know the effect that movie had on Scott to make us the

obvious choices to him. No, it wasn’t designed on our part.

Do you think

you'll help people better understand the Jewish experience, or just

confuse them further?

Joel Coen:

It wasn't really our intent to have people understand the Jewish

experience exactly. That’s because it's just a context for a story

that we found very interesting because of our own direct experience

with so much of where the story takes place and the kind of

community and family that it takes place in. But you're always

trying to be specific, whether it's about your own experience or

whether it's in a context that you don't have any experience in

whatsoever. That specificity is important for the story. It becomes

part of what the story is about, absolutely.

CLICK HERE TO SEE WHAT THE

COEN BROTHERS HAD TO SAY TO US IN 2013!

Email

us Let us know what you

think.