Copyright ©2008 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

February 6, 2008.

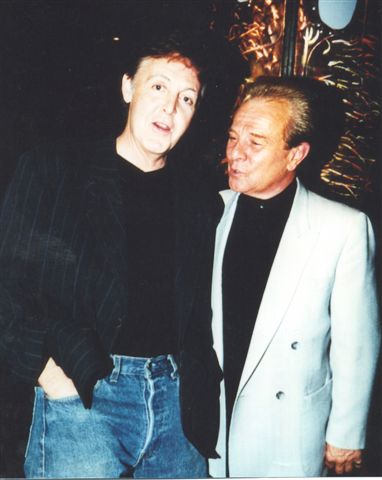

Usually, it's the other way around for Paul McCartney, but in this

instance, it was Sir Paul who had always wanted to meet a certain musician

who had influenced him in his early years.

The year: 2000.

Philadelphia

native Charlie Gracie, the influence in question, was scheduled to play a

small gig in London when the call came from McCartney's people.

"I thought he was pulling my chain," Gracie says when his

agent announced that McCartney desired to meet him that very night. Although

Gracie had his own show to do within an hour, with 1500 rabid fans

eagerly awaiting his appearance nearby, he figured he'd be a sweetheart and

grant Paul's wish.

Gracie was whisked away to a CD release party and press conference

for McCartney's newest recording, which included a cover version of Gracie's

own signature hit from 1957, called "Fabulous." The tune was a decent

success in America, but in Europe (and especially Britain), it was monster.

That,

along with a few of Gracie's other fifties' records, including chart-toppers

"Butterfly" and "99 Ways," were huge in America; however, they also

influenced an entire generation of British rockers – men who would

ironically become household names in America, unlike Gracie himself. His

other hits that were top of the pops in Britain include "Wandering Eyes," "I

Love You So Much It Hurts," and "Cool Baby," all songs that pricked the ear

of a very young McCartney.

"All of the sudden, Paul's manager comes out, grabs me by the hand

like a child in kindergarten and pulls me through the crowd," Gracie

recalls. "'He wants to see you now, Charlie, now!' I turned the corner into

his dressing room, and My God, he's standing there as big as life, with two

big security guards next to him, and a couple of his children and

grandchildren.

"All of the sudden, Paul's manager comes out, grabs me by the hand

like a child in kindergarten and pulls me through the crowd," Gracie

recalls. "'He wants to see you now, Charlie, now!' I turned the corner into

his dressing room, and My God, he's standing there as big as life, with two

big security guards next to him, and a couple of his children and

grandchildren.

"He

put his arm around me and he says, 'Charlie Gracie, I'll never forget when I

came to see you when I was sixteen-years-old in Liverpool. I'll never forget

'Guitar Boogie.'"

"Guitar Boogie," a little ditty that Gracie picked up while

learning to play the guitar in South Philly, made quite an impression across

the pond, on those who were about to rock.

Upon hearing this from McCartney, Gracie recalled, "If I had false

teeth, they would have fallen out of my mouth. I said to him, 'You mean to

tell me that all you've been through in your career, all your fame, all the

money you made, that you remember me playing 'Guitar Boogie?' He says,

'well, you were an inspiration in my career.'"

Gracie concludes the little story with this: "What more could you

ask for in life?"

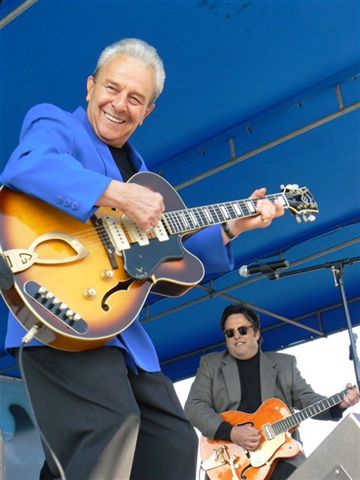

Evidently, not much. Although Gracie is a major draw along the East

Coast (including 5,000 people at New York's Lincoln Center last summer), and

that he returns to Europe annually for a jam-packed, on-stage lovefest, his

career path was not the straight and narrow it may (or should) have been.

Evidently, not much. Although Gracie is a major draw along the East

Coast (including 5,000 people at New York's Lincoln Center last summer), and

that he returns to Europe annually for a jam-packed, on-stage lovefest, his

career path was not the straight and narrow it may (or should) have been.

Although

fortune and major fame had eluded him, he still has his legions, from Sir

Paul to Graham Nash (to this day, Nash's sister still has a cigarette butt

Gracie discarded in 1958) to Van Morrison (who asked him to open for his

tour in 2000) to the mom-mom and pop-pop beachgoers in Wildwood, New Jersey.

Even half a century later, fans are still turning out in droves to see his

rock-the-house shows. Why? Talent, for sure, but even more importantly,

Gracie knows how how to relate to his audience.

"I get emails from all over the world," Gracie says. "People are

fascinated with my career. I never knew why. I never was a druggie, I never

was a whoremonger. I'm just a kid from downtown, trying to sing and play his

way to the end, until they shut the lid."

At 72, and more than 57 years in show business, Gracie is far from over. In fact,

some say it's only just begun.

At 72, and more than 57 years in show business, Gracie is far from over. In fact,

some say it's only just begun.

"I never thought of me as anything," he says. "I just sing and I

play the guitar. I think I do it fairly well,

because I never would have

survived 57 years in this business, but I never claimed to be the best or

the greatest at anything. I just go out there and I do what I do; the people

seem to like it, so I raised my family, I bought my home, I live off the

money I make doing that and it's been wonderful. I can't complain."

Other people, with different temperaments, may not have handled the

same fate with Gracie's grace.

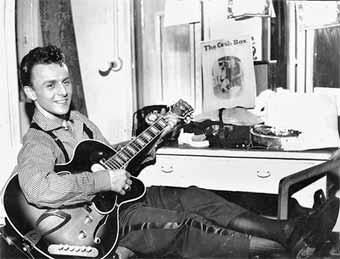

It is commonly agreed that Charlie Gracie was Philadelphia's very

first rock-and-roll star. And that's saying something, considering that the

City of Brotherly Love was home to American Bandstand, as well as

Frankie Avalon, Bobby Rydell, Fabian and Chubby Checker.

He began

making records when he was a mere fifteen, in the pre-rock era of 1951.

Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Buddy Holly hadn't yet stepped into a recording

studio when Gracie recorded "Boogie Woogie Blues" for Cadillac Records. Even

today, it is widely considered to be one of the first rock-and-roll records,

even though the term had not yet been coined.

Gracie

won a series of American-Idol-like talent contests on the hugely

popular Paul Whiteman Show (simulast on TV and radio and aired

nationwide from Philadelphia). After winning week to week to the point that

it was becoming ridiculous, he was given a recording contract.

Gracie

won a series of American-Idol-like talent contests on the hugely

popular Paul Whiteman Show (simulast on TV and radio and aired

nationwide from Philadelphia). After winning week to week to the point that

it was becoming ridiculous, he was given a recording contract.

"Between 1951 an 1955, I recorded several discs for the

Cadillac and 20th Century labels with no great success," he recalls, "but

started to build up the ol' popularity. They would get occasional airplay. A

lot of the black disc jockeys would play them because they thought I was

black.

"This

was 1956, and Elvis is starting to become famous. I met Bernie Lowe, who had

$2,000 in his pocket and wanted to start a record company. He was looking

for the tall, sexy Elvis type, but he couldn't find anybody and he wound up

with me. He came to the house that day. I'll never forget it, because he had

a cold. My mom gave him some tissues and some chicken soup. This was a very

heavily Italian-Jewish neighborhood, so chicken soup was a common thing

between the Italians and the Jews."

Lowe's record company, Cameo

(eventually called Cameo-Parkway), was the biggest and most influential

independent label in the United States between 1957 and 1963 (this was

before Motown). Gracie gave the company its first hits, and opened their

door for other major hitmakers, including Dee Dee Sharp, The Orlons, The

Dovells, The Tymes, Bobby Rydell and Chubby Checker.

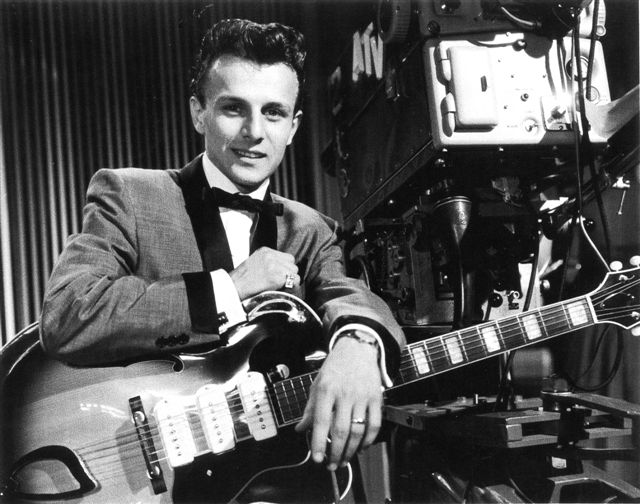

"We went

into the studio in December 1956, maybe two days before Christmas ," Gracie

recalls. "We cut two songs. One was 'Butterfly' and one was '99 Ways.' By

March of 1957, we not only had a hit but a #1 hit. I thought my mother was

going to shake me and say, 'wake up, it's time to go to school!' It was like

a dream."

His fame, as the saying goes, lasted about fifteen minutes, but

what a hell of a quarter-hour it was.

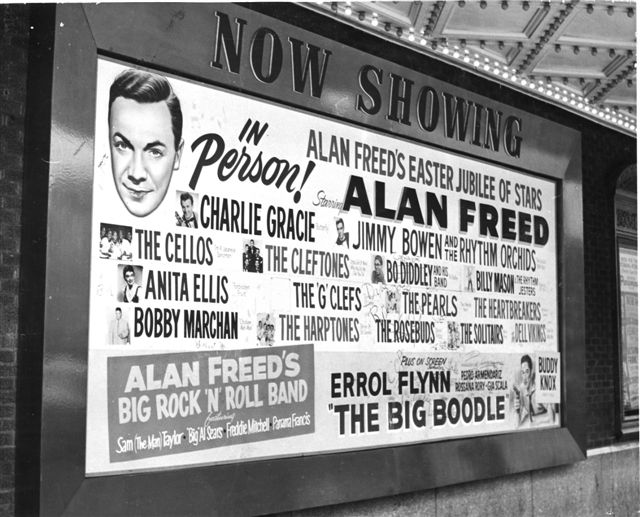

"On the strength of [those hits], I'm doing the Paramount Theater

in New York, The Ed Sullivan Show, Alan Freed, Dick Clark," he recalls. "I

got asked to go to Europe to do the Palladium in London. It was like a

dream.

"On the strength of [those hits], I'm doing the Paramount Theater

in New York, The Ed Sullivan Show, Alan Freed, Dick Clark," he recalls. "I

got asked to go to Europe to do the Palladium in London. It was like a

dream.

"When I made a few bucks, the first thing I wanted to do was get

the hell out of the ghetto and I bought my mom and dad a nice home in the

suburbs. I remember telling my mom to pick out anything she wanted at

Rubin's Furniture, and I signed a check for $12,500.

"My father said to me, 'what do you want, Charlie?' And for me,

every kid's dream is to have a brand-new Cadillac. So the first thing I

bought was a Cadillac.

"The salesman said to me, 'stop touching the car, kid, you're

getting fingerprints all over it.' I said, 'I like this car. I would like to

buy it.' He said, "Oh, you would, huh?" I said, 'how much is it?' He says,

"$5300." Well, that was a lot of money in 1957. So I say, 'Good, wrap it up.

We're taking it home.'

"We took it home that night. You might think I was Frank Sinatra.

My whole family was so thrilled. My Sicilian grandmother was still alive at

the time. The first thing she told me was, 'don't get a big head.' That's

what grandparents are for."

As

much of a smash as he had become in the States, he was considered a god in

Britain, where they were starving for American rock and roll.

"[Before my first tour of Britain], I went to Diamond's on South

Street [in Philly] and I bought some beautiful suits," he says. "In those

days, $300 or $350 was a lot of money, so I had a blue one, a gray one. In

Britain, I'm ready to go out on stage and a guy says, 'Charlie, you can't go

out like that. You look like a Teddy Boy.' I said, 'What the hell is a Teddy

Boy?' I found out that they were like the hoodlums of London.

"[Before my first tour of Britain], I went to Diamond's on South

Street [in Philly] and I bought some beautiful suits," he says. "In those

days, $300 or $350 was a lot of money, so I had a blue one, a gray one. In

Britain, I'm ready to go out on stage and a guy says, 'Charlie, you can't go

out like that. You look like a Teddy Boy.' I said, 'What the hell is a Teddy

Boy?' I found out that they were like the hoodlums of London.

"I only weighed 112 pounds at the time. I was jockey weight. When

the curtains opened up, I didn't even have to sing. The kids looked at me –

I looked like them – and I was a smash. I couldn't even hear myself singing

and playing over the screaming. You might think I was Elvis Presley or

something. But I took it in stride.

"Two shows a day, seven days a week. I was playing to about thirty

or forty thousand people, but in a week's time. Not in one night. I was

making between five and seven thousand dollars a week. My father used to

work two years to make that."

The unraveling came quickly. Gracie may have been merely a kid, but

he was street-smart enough to realize that he was not getting all the

royalty money coming to him from his hit records. The powers-that-be gave

him just enough honey to keep him riding a Cadillac and buying fancy suits.

Nevertheless, Charlie sued his record company. Little did he know

that one of those owners was a considerable power player: Dick Clark, who

was none too pleased. Turns out that Clark was a "silent

partner" at Cameo-Parkway.

Nevertheless, Charlie sued his record company. Little did he know

that one of those owners was a considerable power player: Dick Clark, who

was none too pleased. Turns out that Clark was a "silent

partner" at Cameo-Parkway.

"We settled out of court," Gracie says, "but I never got on

Bandstand again. Clark was part of this little conglomeration going. I was

told, 'you will never have another hit as long as you live.' You know what?

They were right.

"They figure, this guy, Gracie, is stirring up the pot. If

everybody does what he does, we'll be in trouble, so we have to get rid of

him. So the playing of my records gets diminished. I never got it all from

'Butterfly.' I got a hunk of it. It sold over three million records, man. I

thought I was being cheated. I had principle. If I owe you ten dollars, I'll

write the check out tonight and you'll have it in two days. I was brought up

that way.

"A year or two later, new kids are coming up and everybody forgets

who you are. But

I did have a very strong base in Europe because I had more hits there. And I

was only the second American to bring rock and roll there [Bill Haley and

the Comets arguably being the first, and Gracie being the first solo act to

be invited back], so it left an impression on them."

While the musicians he influenced came over and kicked ass, Gracie

was in redux, and began a humble but steady life on the road, grabbing any gig he could

possibly get.

While the musicians he influenced came over and kicked ass, Gracie

was in redux, and began a humble but steady life on the road, grabbing any gig he could

possibly get.

"So I said, this is it. I'm just going to have to be a working

musician," he says. "I'll work five, six, seven nights a week. Making three

or four hundred dollars a week, whatever it was at the time. I went from

rags to riches to rags. I had to start all over again. I had a wife and two

kids. I can't walk around like Frank Sinatra and act like a big shot when I

didn't have any money.

Gracie's

agent, Bernie Rothbard (who had worked with him for 36 years, on a

handshake), kept him going with consistent gigs in

clubs, resorts and oldies shows.

"He was like a father figure

to me," Gracie says of Rothbard.

His agent's dedication allowed

Gracie to make a surprisingly comfortable living as a full-time musician.

Of course, his rock-solid talent, and his love of performing, kept the

infatuated crowds returning for decades. Although he never again ascended

the superstar heights of the fifties due to industry politics, he had the

love of his family and his growing legions of fans to keep him warm.

A change

came in 1979, when a Canadian record producer named Richard Grows wanted to

reissue Gracie's old recordings. The collection caught on in Britain, and

then all over Europe.

A change

came in 1979, when a Canadian record producer named Richard Grows wanted to

reissue Gracie's old recordings. The collection caught on in Britain, and

then all over Europe.

Gracie's phone started ringing.

"It gave me confidence once again in myself and my career," he

says.

The venues were smaller, but the audiences seemed even more

enthusiastic than ever.

"I

survived it all," he says. "If the trends changed, I changed along with the

trends, but I never lost my base sound. People come to hear the fifties

music when they come to hear me. More so in the last ten years than even

before. Everything runs in a cycle in life. You know how it works. That kind

of music is catching on all over again. In Europe, I get younger and younger

people coming to see me all the time. Even here in the States. It's

amazing."

Through it all, Gracie remains a hometown boy, making Philly his

base.

He says,

"Stardom came to me, and when I look back on it now I was still immature.

I'm a better musician now than I was fifty years ago. But I played good

enough and well enough that I could go out there and kick the ass out of an

audience. Sure, I'd like to have four or five million in the bank, but it's

not meant to be."

He says,

"Stardom came to me, and when I look back on it now I was still immature.

I'm a better musician now than I was fifty years ago. But I played good

enough and well enough that I could go out there and kick the ass out of an

audience. Sure, I'd like to have four or five million in the bank, but it's

not meant to be."

Though so

much has changed around him, much of Gracie's life remains constant. He is a

family man, first and foremost (he will be happily married to his wife for

fifty years this year). He still reveres the memory of his parents and

grandparents, who encouraged him to pursue his love for music despite its

lack of promise for long-term security. And he considers his fans his

family. Talk about close relations!

Gracie's unique story is as unpredictable as

the path of a butterfly. However, one thing you can't do is call his

resurgence a "comeback," since essentially, he never really left.

Nevertheless, Gracie remains grateful for his lifetime mission of making

people happy.

"God is merciful," he says, "and if you

walk the walk and talk the talk, you got nothing to worry about."

Email

us Let us

know what you

think.

Features

Return to the features page.