Copyright ©2006 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

July 24, 2006.

“Burt Bacharach’s musical contribution was very beautiful, wonderful, warm

music that everybody liked and admired,” raves Brian Wilson. “His

uniqueness lay in his chord patterns. The chords in ‘Walk On By,’ ‘Here I

Am’ and ‘Do You Know The Way To San Jose?’ are really great.”

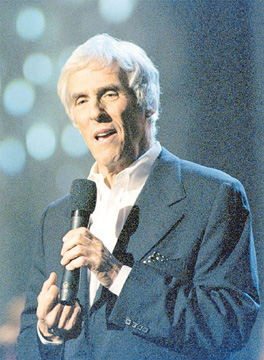

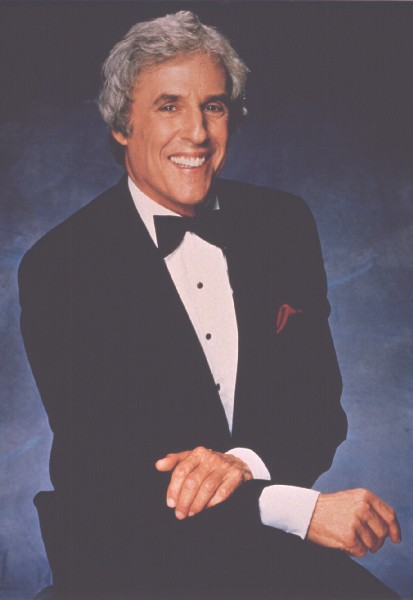

Championed as one of the 20th century’s most seminal and

inventive composers, Burt Bacharach, with partner Hal David, created some

of the most sophisticated, complex and beautifully crafted pop songs ever

written. The list of Bacharach/David evergreens is truly mind-blowing.

“Walk On By”… “I Say A Little Prayer”… “The Look Of Love”… “Raindrops Keep

Falling On My Head”… “Do You Know The Way To San Jose?”… “A House Is Not A

Home.” It’s enough to send any aspiring songwriter back into a cave for

another fifty years.

Whether it’s his landmark recordings with Dionne Warwick, seminal work on

such films as Alfie, Casino Royale, What’s New Pussycat?,

and Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid or his recent acclaimed

collaboration with Elvis Costello on the Painted From Memory album

and high profile appearances in the Austin Powers films, Bacharach

continues to enthrall generation after generation of listeners. He does

it with his urbane cool, elegant musicality and those haunting,

unforgettable melodies.

And

at age 77, Burt Bacharach is showing no signs of slowing down. He’s just

released a provocative new solo album, At This Time, which is a

striking departure from his previous work, earmarked by a gritty political

slant, drum loops courtesy of Dr. Dre and guest appearances from Costello,

Rufus Wainwright, and Printz Board of the Black Eyed Peas.

What made you decide to

become a songwriter?

I

don’t think it was in my blood to become a songwriter. I wasn’t sure what

I wanted to do. I always had an ambivalence about my music, whether I

wanted to pursue or it didn’t want to. I kinda just drifted along. My

mother made me take piano lessons, which I never wanted to do. I hated it.

So what I did was went along with her wishes and practiced the piano and I

didn’t really have a lot of ambition in life. I didn’t know where I was

gonna go, whether I was gonna wind up in the clothing business because

that’s where my father had connections. You might say I floated and let

things happen to me. I did get my first job playing piano for Vic Damone.

I played piano in bars before that. I wasn’t bad but I wasn’t great. I

wasn’t writing songs then when I was with Vic Damone.

What

inspired you to start writing songs?

What

inspired you to start writing songs?

I

didn’t last very long with Vic Damone, maybe three or four weeks of actual

dates. Maybe I wasn’t good enough or experienced enough because I was

trying to conduct and play. But he went through a lot of people so I can’t

have any regrets about it. What happened was the next job I had was with

The Ames Brothers. They were these good guys, these four brothers from

Boston and they had some hit records. They had a big hit with “You, You,

You.” They sang pretty simple songs and when I was out on the road with

them I heard all of these demos that would come in and they would all

sound real simple like “You, You, You” and I thought this could be very

easy. I could write five of these a day. I quit my job with The Ames

Brothers and went to New York to start writing. I had some connections and

I started writing with some people and met some other people. I worked in

the music factory, the

Brill

Building five days a week with different lyric writers. It wasn’t easy.

The dream of thinking you can write five a day or even five a week wasn’t

gonna happen. I was trying to write real simple and familiar songs. I went

a long time, maybe a year and a half without getting a song recorded. The

first cut I got was a Patti Page record somewhere around the year and two

month mark. It was a song called “Keep Me In Mind,” which was a pretty

ordinary song.

When do you think you found your voice as a writer?

Well, I think I was writing some fairly good songs as I got into it. I

always tended to be comfortable with R&B. After I had my first hit, which

was “Magic Moments” with Perry Como, and the same time a song called “The

Story Of My Life” by Marty Robbins. That was a great feeling because we’d

broken the ice. But after that I think I wrote some fairly good songs,

made demos and put it in the hands of some A&R people. You had to go

through somebody else producing the record. I very rarely liked the way my

songs got done. I did like a couple of hits I had with The Drifters

produced by Leiber and Stoller because they were really good. They knew

what they were doing. I had “Mexican Divorce” and “Please Stay” with them.

But my voice really as a writer came when I was suddenly able to make my

own records with someone like Jerry Butler on “Make It Easy On Yourself.”

Calvin Carter said, “You go write the orchestration yourself and conduct

the band and get it the way you want it.” It was a hit and once I found

someone who let me in the studio to take my song and do it there was big

difference. Did I ever really want to be a producer? No, it was really out

of self defense. It wasn’t about the money I’d make as a producer or how

big a cut I’d get. It was just to protect the song, protect the material.

And then I worked a lot with the Scepter label with The Shirelles, Chuck

Jackson, Tommy Hunt and of course, Dionne (Warwick).

Once we had Dionne Warwick we had our voice. And the more I saw that

Dionne could do musically with the material and how wide her range was and

what she was capable of the more chances and the more experimental and the

more risks I could take.

Your songs stood out from everything else on the radio in the Sixties.

Were you aware that you were forging new ground?

I

knew I was doing things different but at the same time I was doing things

that very natural for me. I wasn’t trying to break any rules. But I wrote

the way I heard things. When I step away from a piece of material I never

wanted to make it too much of an effort for the listener, for an audience,

make it too difficult for them to clock. I wanted to make it as successful

as possible. You take a song like “Promises, Promises”, it’s a very hard

song to sing but with Dionne it was effortless. But if you’re in a

Broadway show and you sing that every night it’s hard. But the intent

there is to make it work for the show and express the anger that the lead

feels in making a statement like “Promises, promises, I’m all through with

promises.”

Do

you write with visuals in mind?

Do

you write with visuals in mind?

I

tried to hear the voice I was writing for. That was important. What Dionne

would sound like or what Chuck Jackson would sound like on “Any Day Now.”

If you knew what the voice was like you could tailor make the material.

But for me, the song would always go hand in hand with what was around the

song, the orchestration. It kind of came together. I’m much happier when I

orchestrate myself, make the record myself , nobody changes chords on me.

If the record doesn’t work and I missed then I missed. I can blame myself,

not the arranger and not an A&R guy.

As a pianist, your choice of chords, inversion is very sophisticated. What

shaped your approach as a player, your music theory and composition

education?

You take it from everywhere. You take the exposure to music. If

I’m ever asked about what advice I can give to young students or young

aspiring composer it’s learn the rules. Learn how to write music down. Get

a wide range harmonically of where you can go instead of a three, four,

five chord range.

Expand your palette?

I

was exposed to a lot of music starting with Darius Milhaud. I was exposed

to John Cage but I didn’t study with him. Henry Cowell was a big one. It’s

what you take in, what you feel, what you hear. You know if you listen to

twelve-tone music, if you listen to the music of jazz, which appealed to

me. Be-bop, Dizzy Gillespie, Theolonious Monk, Charlie Parker. You gotta

be like a sponge.

You said hearing some of those jazz artists was like “a window opening."

Yeah, because I heard music that I thought I liked before, big band stuff

like the Dorsey Band or Harry James. It was good but it wasn’t like when I

heard bop and Dizzy’s big band. They were playing things that were fifty

years in front of anything else going on. I’d go see a lot of those people

in New York City. It was great, going into 52nd Street where

these little clubs were. There were more people in the band than there

were in the audience. I saw a lot of people. I saw the (Count) Basie band,

which never played in clubs. Great band, what a band! I had to use my fake

ID because I couldn’t get into these clubs, I was too young. I did sneak

in and loved it.

As a writer, I understand that you don't believe in waiting for

inspiration to hit, you just work and work at it.

I

think what you do is be in touch with your music, even if you just

improvise and have contact with it. Twenty-minutes, an hour a day. When I

finish this interview I’ll go the piano and maybe I’ll get something and

maybe I won’t. But it’s no different than a tennis player on the circuit.

He can’t say ‘I’m not gonna play any tennis for the next couple of weeks”

unless of course if he’s injured. I write differently than other people.

I’ve got to get away from the piano and hear it, laying down the couch or

something in the music room where I can hear the whole thing, what’s going

on orchestrally. If you sit and write at the piano I feel it bar by bar

but I don’t have a total picture of the balance of the whole thing. I

gotta hear it away from my instrument. That’s’ not to say you can’t write

at your instrument, too many people have been doing it for years

successfully, whether you play guitar and write. They get a whole thing

top to bottom. Me, I’ve just gotta stand back.

Then

I’ll go check it at the keyboard and make sure the chord I’m hearing is

the right one. You’ve got a limited time to say what you wanna say and you

have to say it and not beat an audience or yourself up. I’ve heard records

that sound really great for four, five hearings and by the sixth, it bats

you up and wears you out.

Then

I’ll go check it at the keyboard and make sure the chord I’m hearing is

the right one. You’ve got a limited time to say what you wanna say and you

have to say it and not beat an audience or yourself up. I’ve heard records

that sound really great for four, five hearings and by the sixth, it bats

you up and wears you out.

Your writing partnership with Elvis Costello on the

Painted By Memory

album and especially the song “God Give Me Strength” was extraordinary.

How did that writing process work with Elvis?

On

“God Give Me Strength” I had a real limited time with Elvis Costello. It

was for a movie and we had maybe five days to get it done. Elvis was in

Ireland or England and I was in L.A. We had met and had known each other a

little bit, running into each other in a studio. I respected him and he

respected me and we felt we could write this. He sent me a tape or dump it

on my answering machine and I’d send the same thing back. We’d also do it

by fax and that’s how we wrote it. We wrote it rather quickly. Certainly

inside a week, maybe five, six days. We never knew how long it ran. I

wrote the orchestration while I was down in Florida and came up to record

it with Elvis in New York and we had never really sat down at a piano and

figured out what key he would sing it in. I wrote the orchestration, wrote

the figure at the beginning and the end. We didn’t even have a sense of

how long it was. We were astonished in the studio, it ran over six

minutes. There was no thought of cutting it. Sometimes I hear four-minute

records that feel like they run eight minutes. If it stays interesting you

don’t touch it. I was very pleased with that song. I was pleased with the

whole album. That started our whole collaboration of Painted From

Memory. Writing “God Give Me Strength” went so well that Elvis and I

both agreed we should try and write a whole album.

You worked with Elvis on your new CD,

At This Time.

I

called Elvis in Italy. The track was finished. I put a temporary vocal on

the track “Who Are These People?” and just sent Elvis the record with me

just singing the verse, which would be his entrance and then different

spots that Elvis would be involved on the record. He was in Italy. Gosh,

it was just last summer. He was right on board. Politically, he’s even

more extreme than I am about what’s going on in this world and with our

government. Elvis said he would do it. He put his vocal on in New York. We

did with a telephone hookup, Elvis in New York and me in LA. Elvis came in

and sang the lyrics, “this stupid mess we’re in is just getting worse, so

many people dying needlessly. Looks like these liars may inherit the

earth, even pretending to pray and getting away with it.” So Elvis was on

board, spectacularly so and he comes in with the anger and the rage that

he used to feel on some of his early record, which is what I was looking

for.

You

said that you feel

At This Time is the most important

album you’ve made, why?

You

said that you feel

At This Time is the most important

album you’ve made, why?

Well, because it’s the most honest album in a sense. It certainly doesn’t

mean it’s going to be the most successful. I just had to say what was on

my mind. The title of the album refers to at this time in my life

represents how old I am, about my young kids and this crazy mess that

we’re in. And so the lyrics had to be representative all the way through.

It’s a different kind of form. It didn’t intend to be that way. There’s

music and then there’s a vocal that comes in after eight bars and then

there’s vocal interjections, observations. It was the first time that I

ever played with writing lyrics. I did it with Tonio K. And that was also

part of it because the music made me hear words. It made me hear what I’d

like to say lyrically. I’d always put dummy lyric on melodies. It’s okay

to do that. It just helps me because rather than sing (sings melody),

you sing “feel like holding on.” It’s a different kind of thing, and maybe

it makes no sense but it’s got more expressiveness when there’s some kind

of language to it. The shape and the form of this album just kind of took

place. The first song that I wrote was “Please Explain,” which was to a

drum loop, which came of out (Dr.) Dre’s studio. It’s very restrictive. It

had a bass line that repeated every four bars. It almost told you what the

chord structure had to be. It’s challenging because you have to write a

melody over that.

That song includes a mention of “What The World Needs Now”, which is some

ways was also a protest song.

Yeah, but gentle. But that’s why there is this umbrella over this album.

It’s still the same, what the world needs now is love. That’s why there’s

an interjection on “Please Explain.” (recites lyrics) “There was a

song I remember said ‘what the world needs now.’ That was Tonio K’s idea.

He said, “Drop that in.” Tonio K is great to write with. I don’t say it’s

“love” because that would be too on target. You have to listen to this

album. It’s not like something you play for dinner music. I also think in

a way I am still writing love songs. You can say that I wrote love songs

about heartbreak, “Only Love Can Break A Heart.” (recites lyrics)

“Make it easy on yourself because breaking up is so very hard to do.”

Songs abut love being in trouble or love splitting or love being in

danger. So instead of writing a singular love song, me with another person

or writing about two people. I’m really writing a love song about a lot of

people that have been fractured and shattered and hurt. The cycle of

violence in the world has robbed the love. But I’ve also tried to make the

music melodic. It’s either melodic or it isn’t melodic. It’s natural for

me. In my case it better be melodic. So you pull away the words, you pull

away the meaning, it better be memorable My intent or my hope is that he

melodies will be memorable.

What do you listeners

take with them after hearing

At This Time?

What do you listeners

take with them after hearing

At This Time?

First of all, I’m making a statement here. Here’s a guy that wrote love

songs all his life, never rocked the boat, never was political and that in

itself says something. At this time in my life, it’s sort of like the

Peter Finch character in Network, “I can’t take it anymore. I don’t

wanna take it anymore.” So whether it shakes up some people or some people

will say “it’s too rich, it’s too tough, give me some hip-hop” or “give me

a novelty song like ‘Who Let the Dogs Out.’ Give us some laughs.” There

was no choice for me. This record started with my label in England,

Sony/BMG, and they urged me to do a different kind of record, take

chances. So having that permission and not having anybody look over my

shoulder was great. There’s on track on the album that I hope we get it

played on radio, it’s not gonna be easy. With Painted From Memory I

don’t believe we ever got one cut played on the radio, which is amazing.

I’m not even sure if it was ever attempted to service radio because radio

is so tough. Radio is really difficult now. The Arethas, the Gladys

Knights, Patti Labelle… there’s an R&B, urban station level. There’s no

sure thing, there’s no sure thing at all.

Has songwriting become easier for you over time?

It’s

always challenging. It’s always a process. It’s never been easy and never

will be. I don’t know where I will go next. It’s very hard for me to go

backwards. I don’t know if I can sit down and write a song for one of the

next ten contestants on American Idol and to send it to Clive Davis

who will turn it down.

Did that happen?

I

love Clive, I really admire him. He’s a real survivor, he’s resilient and

really cares about music. But he has his own ideas on how he does things

and it’s successful. I can remember one time getting an award at the same

dinner where Clive got an award. He’d already got his award and then I got

my award. I said, “It really is great to have this award but that doesn’t

change the parameters on what exists. Because the next song I write I can

send it to Clive if I want and have him turn it down, like he has the last

sixteen songs.”

There

was such a cross-pollination of styles and genres in your music, from

bossa nova to be-bop, jazz to classical, pop to R&B. Speak about bringing

a wide swath of influences into your writing.

There

was such a cross-pollination of styles and genres in your music, from

bossa nova to be-bop, jazz to classical, pop to R&B. Speak about bringing

a wide swath of influences into your writing.

First of all, I’ve got the capability of the language of going into

different time signatures and that comes from the foundation of learning

and classical training. It’s also just that I’m sponge like. What I’ve

heard, what I’ve absorbed, what I like in music and it comes out. It’s

accessible for me to touch. It’s not hard. I don’t have to say “let me go

here or here.” I’ve always been crazy about Brazilian music. It’s the

freshest music. Cuban music, too. But Brazilian music is really

interesting because it’s completely fresh.

Can songs still make a difference today?

You’re talking about making a difference politically? No, I don’t think

so. What’s going on is way too intense and horrible. You can speak your

feelings like making a speech or writing an Op-Ed article. I wrote my

piece on this album, At This Time because this is how I feel at

this time. There are no time length considerations like “This runs seven

minutes almost, how are we going to get it played on radio?” It’s not

important. There is an accessible cut on the album that if we get a chance

at radio certain formats might play it. That song is “Go Ask Shakespeare”

with Rufus Wainwright. I made some edits on it and it’s down to a shorter

radio version. When I got the first four tracks to Rob Stringer in Italy,

he runs Sony/BMG in England, he’s the chairman of the board. It was his

idea for me to make an adventuresome album. He said, “make an

adventuresome album, Burt. Take chances.” I said, “Well you know, I’ll

bring you these four and they’re not complete.” One of them was “Go Ask

Shakespeare.” I had a temp vocal of me singing at the end. Rob said, Let’s

see who could we out on there to sing it?” He came up with Rufus and I

said “I like Rufus a lot” so it was agreed right there to get him involved

with the record. I called Rufus. I got his number from a mutual friend,

Steve Tyrell. I met him once in New York. He said to send him the track

and he called back and said he loved it and would be glad to do it. That’s

how it happened. He recorded it in

England. We sent him the pro

tools stuff. It came out great. What I like about the album is there are

not predictable artists on there. Well you might say the association from

Painted From Memory that Elvis is predictable. But Rufus, yeah,

that’s different. Then you’ve got the Dr. Dre drum loops and there’s

Printz Board from the Black Eyes Peas. And you’ve also got Chris Botti who

is this marvelous musical presence. This speaks very well for music that

Chris Botti is having the kind of success he’s having. Basically a jazz

rooted trumpet player crossing over a little bit playing old songs

beautifully like “My Funny Valentine”. So there’s a hopeful side for

music. How much you’ll get played on radio doesn’t seem so important. But

it’s great to see a jazz instrumentalist to have a success. Who was the

last one? Kenny G. It doesn’t happen often.

Why do you feel your songs connected more with female singers, people

like Dionne Warwick, Dusty

Springfield, Karen

Carpenter, Petula Clark, Jackie DeShannon?

I

don’t know if there’s any way to analyze that except I just like working

with the female voice more than the male voice. Maybe it’s more expressive

and maybe it’s my feminine side coming out and being reflected by a female

voice. But yeah, I’m comfortable with it. The exception might be the album

I did with Ron Isley two years ago. He’s really a great soulful singer.

I’m always comfortable there. Chuck Jackson, Ron Isley. But I’ve done

records with white male pop artists. Bobby Vinton, Gene Pitney, B.J.

Thomas.

Herb Alpert?

Yes,

right. I never thought “This Guy’s In Love With You” was gonna be a big

record. It was a television show. Herb was very hot and his band, The

Tijuana Brass was very hot. I was signed to A&M as an artist. There were

great guys running the record company, Herb and Jerry (Moss). They asked

me to do it, to write a song with Hal David, come in and write the

arrangement and conduct the orchestra. I did it as a favor. If you asked

me when I got in my car leaving Gold Star Studios that night and thought

this was ever gonna be a hit I would have said no way. Then three or four

weeks later it was number one. Wow!

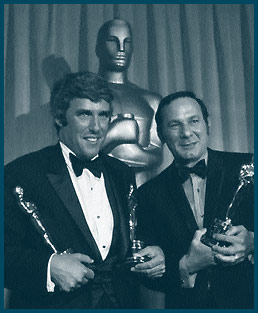

Writing a great song, how long does that feeling stick with you?

It’s

like winning an award. It’s great when it happens. It’s like winning an

Academy Award or winning two with Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid with

“Raindrops (Keep Falling On My Head”). You can’t get a more extreme high.

You bask in it the next day but then you’ve gotta move on. You know? You

have to move on.

What

made your partnership with Hal David work?

What

made your partnership with Hal David work?

Eventually

it did work with but it didn’t work at the beginning. We wrote some

terrible songs. Everybody was writing with everybody else, taking turns.

You wrote with a different lyric writer one morning and then a different

lyric writer the next day. Hal was nice enough and he had some hits and he

was more experienced than me. But we wrote some bad songs initially

whether it was “Underneath The Overpass” or “Peggy’s In The Pantry,” songs

you’ll never hear. Hal is really good. I didn’t realize how good he was.

For me what was most important at the time was whatever the words he used

would sound on the notes. They didn’t have to mean much. They didn’t have

to really make sense but if the note needed an open sound that’s what I

was looking for. If it didn’t make sense then that was okay. But now when

I hear Hal’s words I’m struck by how great he is. A lyric like “Alfie” is

as good as anybody could ever write. I’ve grown to appreciate his lyrics

so much more. Back then I was much more interested in what the music said.

It’s just my way of going. Hal and I had these couple of hits, which

helped give us some kind of foundation. When you finally succeeded and you

get something off the ground like we did with “The Story Of My Life” with

Marty Robbins and “Magic Moments” with Perry Como, there was such a relief

that you had some success. Just to be in the glow of having two hits.

Finally. Even if it’s nothing like I would turn out to write later. Those

songs were really different for me. I think we started writing different

kind of songs. We wrote “Message To Michael” and “Message To Martha” and

“Make It Easy On Yourself.” Things opened up at Scepter. Once I started

making records myself we started making different kind of songs. We had

nobody looking over our shoulder. No A&R man saying, “I like the song but

it’s a three bar song. If you make it a four bar phrase I’ll give you so

and so as an artists.” I would do it and ruin the song. And Hal as very

easy to work with. He would give me the lyrics or I would give him some

music. As far as hammering out together we both liked to go our separate

ways. I’d go home, he’d go home and we’d meet the next day. Sometimes Hal

would have a large part of the lyric done like on “A House Is Not A Home.”

We did really good work. Nothing lasts forever. Not the relationship with

Hal or Dionne and me. You just can’t sustain. That’s one thing that I

totally believe. As an artist or a writer you can’t sustain. I’ve had high

points and I’ve had low points. You have to feel fortunate that you had

some highs and lows, some peaks and valleys. What have I had, four, or

five ups and downs? An artist is very tough. Unless you’re an artist that

doesn’t depend on recording. Like Tony Bennett will work as long as he

wants to work. He’s a major artist and a major voice.

With Hal you had a flurry of pop hits but also found a niche doing film

work, from

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance to Casino Royale.

What made your work well suited for film?

Well a lot came from scoring the motion picture. When I’m scoring a

picture, whether it’s Butch Cassidy or Casino Royale or

What’s New Pussycat?, all those melodies that turned into what became

hit songs came from what I saw on the screen when I was scoring and what I

heard. The first thing is you service the motion picture. If you’re lucky

enough and you have a theme that turns into a hit whether it was Dusty

(Springfield) singing “The Look Of Love” in Casino Royale, what was

most important there was the sexuality of Ursula Andress wearing very

little clothes and making very sexy theme with the saxophone playing the

melody of “The Look Of Love.” Then we put Dusty on. First and foremost is

it’s written for the picture, you don’t force it in. With “Alfie”, the

lyric had to come first because it had to say what that movie was all

about. It’s a different way of going. I think if you’ve got a theme like

“What’s New Pussycat?” and that music comes from watching Peter Sellers

and his craziness in that movie and you’re trying to make it that way and

out words to it. Then you get Tom Jones to sing it, you get lucky. Here

was a theme, which was basically an instrumental, and if it’s a good

melody you’ll always fit words. That’s the way I figure.

What were your thoughts on The Beatles cover of “Baby It’s You”?

Isn’t that flattering to be a composer and have a song recorded of yours

by The Beatles? (laughs) It’s more feeling very privileged than

loving the particular way it was done. But hey, how many composers can say

they’ve had a song done by the Beatles? I really liked what Lennon and

McCartney did as songwriters. They’re just major, major writers. They

broke a lot of barriers down. I think they are brilliant but I also think

that George Harrison is if not as good, just about as good. He was great.

John Lennon and Paul McCartney were certainly fans of your work but did

they inspire you as a writer?

Probably subliminally. But I think what was happening at the time in pop

music was great. I liked what Marvin Gaye was doing with “What’s Goin’

On.” What was coming out of Philadelphia. “Papa Was A Rollin’ Stone.”

Diana Ross with “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” there can’t be a better

record than that. It’s just the way I feel. I react more to R&B.

You recently saw The

Rolling Stones at The Hollywood Bowl.

Yeah, it was the first time I ever saw them in concert. I loved it. It was

a great experience to be there with my twelve-year old son, Oliver, my

internist and my wife, Jane. I loved the energy. Mick’s unbelievable

(laughs). It was such a high being backstage and seeing Ronnie Wood

who I have known and Keith (Richards). Just to see the joy on Oliver’s

face meant so much to me.

You first met Dionne Warwick in 1961 at a Drifters session. What drew you

to her?

Dionne was part of a group. There were four in that group. Cissy Houston,

who is Whitney’s mom. Dionne’s sister, Dee Dee and Dionne’s cousin, Myrna.

They were a brilliant group and they made a sound. We used them behind the

Drifters on the song “Mexican Divorce.” Dionne looked like a star. She

just had a kind of look, the way she was dressed, her bone structure,

pigtails. I didn’t know she was the best singer. Visually she was just

kind of shining through. She came in to sing for Hal and myself about six

weeks later and that was it. We heard her by herself and signed her to

Scepter and the rest is history.

Can

you pick a track or two you write with Hal that you deem worthy of

rediscovering?

Can

you pick a track or two you write with Hal that you deem worthy of

rediscovering?

“Windows Of The World” was a bad record I made. It should have been a

better record. Not sensitive enough. Important song. People know it but it

never was a hit.

You’ve appeared in all

three Austin

Powers films, which has given you a cachet with a younger generation?

Yeah, I was in all three films. Mike Myers loved my music and wanted me to

part of that first motion picture and then used me in the second and then

the third. Sure, that just exposed me to a lot of different people, a lot

of different young people. Young kids. That’s a great feeling. That is a

real blessing.

Select a few songs that

you didn’t write that give you goosebumps.

I love the Michael Masser and Linda Creed song “The Greatest Love Of All,”

that’s really good. That’s a pretty good goosebump song for me. “Ain’t No

Mountain High Enough” by Diana Ross is another one. Earth, Wind & Fire

“After The Love Is Gone,” that’s killer. Also, “Reasons” by Earth, Wind &

Fire.

What was your take on

60’s rock bands doing your tunes like Manfred Mann and Love with "My

Little Red Book"?

Love

had a hit with it. Wrong changes and all, and I never loved that. There

were a couple of chords that were wrong and it would have been better with

the right chords. It’s called people reading music, people reading a lead

sheet then you know what the right chord is (laughs). But I liked

their energy on the song and I liked that it was a hit. Manfred Mann had

the right changes but it was a bad record. I made the record with them.

It’s just a very nervous sounding record. They were uncomfortable with

that song. Again, that came from a picture, I think it’s from What’s

New Pussycat? or Casino Royale. Manfred had a tough time

playing it. It took forever to make that record. But different language,

different harmonic language. I like the song “My Little Red Book.” When

Elvis (Costello) and I were doing concerts he would do that and it was

great.

Lastly, I’d like to have you riff on some of your

most well-known songs starting with “Walk On By.”

“Walk On By” was the first time that I tried putting two grand pianos on a

record in the studio. I can’t remember if I played and Artie Butler played

or if Paul Griffin and Artie Butler played but here were two grand pianos

going on. I knew the song had something. It was a great date. I walked out

of that studio and we had done two tunes in a three-hour session, “Walk On

By” and “Anyone Who Had A Heart.” I felt very good leaving knowing that I

had two monster hits on my hands. You never know for sure but you feel a

great satisfaction.

“I Say A Little Prayer”

I

never thought

I made the right record on that. I think I made the tempo a little too

fast, a little bit too nervous with Dionne. I didn’t want the record to

come out but got overridden. I’m glad that I got overridden. “I Say A

Little Prayer” with Aretha (Franklin) is just a better record.

“I'll Never Fall In

Love Again”

“I’ll Never Fall In Love Again” was written quicker than any song that I

ever wrote with Hal. I had just gotten out of the hospital. I’d been on

the road and gotten pneumonia. We were on the road with Promises,

Promises and we’d try to get this song written and into the show the

next night or two nights later. That’s where Hal’s line came from,

(recites lyric) “what do you do when you kiss a girl, you get another

germs to catch an ammonia, after you do she’ll never phone ya.” So having

been in the hospital for five days with pneumonia, I got out and struggled

to write that song feeling not too great. You should take a rest after

that and not go back into the Broadway show environment out on the road,

Jesus!

“Anyone Who Had a Heart”

It’s very rich, it’s very emotional. It’s soft, it’s loud, it’s explosive.

It changes time signature constantly, 4/4 to 5/4, and 7/8 bar at the end

of the song on the turnaround. It wasn’t intentional, it was all just

natural. That’s the way I felt it.

“The Look of Love”

I had Dusty sing that very sexy. Dusty was very open to suggestions. To

listen to the vocal back with her she’d have to go into a control room to

hear it. She wanted to hear it alone. She was very tough on herself. But

she did a great job.

“What's New Pussycat?”

Again, written for Peter Sellers character. It was an instrumental first

and then words were put on it. If it’s got a good melody it can always fit

the lyric.

“Alfie”

“Alfie” could be as close to the best song Hal and I ever wrote. It was a

hard one to write because most of it had to be said lyrically at first. I

had to set it musically and it was challenging but it turned out great. We

went in and recorded it quickly with Dionne because the original record

was with Cher.

Sonny (Bono) made the record with Cher and that was different than how I

had envisioned it.

“What the World Needs Now Is Love”

Dionne rejected that song. She might have thought it was too preachy and I

thought Dionne was probably right. Hal pushed me to play it for Jackie De

Shannon who we were gonna record. Otherwise I would have let it be and it

would still be in the drawer. Once I heard Jackie sing four bars of it, I

thought “Jesus, this is great.” Jackie had such a great voice. Love her

voice. Whether it’s a song she wrote herself or singing “What The World

Needs Now Is Love,” she’s special. I wish we could have repeated that

success with Jackie but the material we gave her on the next session

wasn’t as good.

“Do

You Know The Way To

San Jose?”

“Do

You Know The Way To

San Jose?”

Dionne did not want to record that song. She didn’t like it. But we talked

her into it and she did it. Her mind changed once it was a hit

(laughs). I knew it was a pretty special song and I knew it was a

different kind of song, too.

“Any Day Now”

I wrote that song with Bob Hilliard, a wonderful lyric writer, not that we

wrote that much together but it was in the

Brill Building days. I

thought it was a pretty good song, a good R&B song. We’d been doing that

song in my show with John Pagano, up-tempo, it’s pretty funky and it’s

good.

“Wishin' & Hopin'”

“Wishin’ And Hopin” was a B-side of Dionne’s and Dusty (Springfield)

covered it. I remember talking Dusty into putting the record out. Dusty

was always very insecure, about what to release, about her voice. What a

great singer. Powerful. She was a great girl. “Wishing And Hopin’” was

great and it was a big hit.

“Raindrops Keep Falling

On My Head”

“Raindrops” was done for the score. When you’re scoring a motion picture

you service the picture and there was that scene with the bicycle. I did

keep hearing that title, I must say. That is my title, “Raindrops Keep

Falling On My Head.” Hal tried to change it and come up with another lyric

but it never seemed to work as well. I watched the film so much when I was

scoring it. It was a convenient way to get B.J. Thomas to sing it because

he was in the stable of Scepter at the time. Our first choice was Ray

Stevens. They flew Ray out to see the picture and hear the song but he

didn’t like the picture and he didn’t like the song.

This

interview originally appeared in the UK magazine Record Collector.