PopEntertainment.com >

Feature

Interviews - Actors > Feature Interviews -

Actresses >

Feature Interviews A to E >

Feature

Interviews P to T >

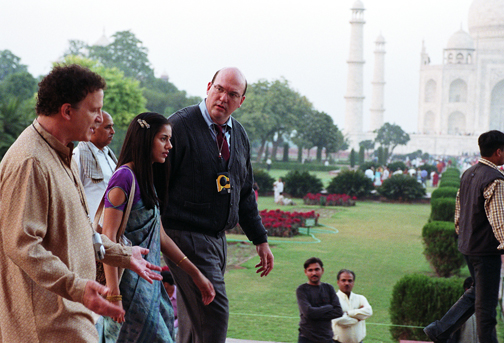

Albert Brooks and Sheetal Sheth

Albert

Brooks and Sheetal Sheth

Albert

Brooks and Sheetal Sheth

Looking for Symmetry with the Muslim World

by

Jay S. Jacobs

Copyright ©2006 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

January

20, 2006.

Albert Brooks is no

stranger to controversy. He has done comic films mocking love (Modern

Romance), death (Defending Your Life), consumerism (Lost in

America), family

(Mother), artistry (The Muse) and the voyeuristic tendencies

of the American people (Real Life).

Still, the respected

filmmaker is a little taken aback by the reaction to his latest film, a

comedy about understanding cultures called Looking for Comedy in the

Muslim World. In the film, Brooks plays an obtuse, whiny comedian also

named Albert Brooks, who is approached by the US Government (in the guise of

former-Senator and actor Fred Dalton Thompson of Law & Order, also playing a

fictionalized version of himself) to take part in a top-secret study.

Brooks is asked to go to India and Pakistan to foster cultural understanding

by trying to find out exactly what it is which makes the Muslim people

laugh.

Brooks chose as his female

lead New York-born Indian actress Sheetal Sheth, who had grown up in the

United States but visited family in India regularly through the years. The

film is a big break for Sheth, who has made respected indie films

such as

ABCD, Wings of Hope, A Pocketful of Dreams and Dancing In Twilight.

She has also appeared in the series The

Agency and Line of

Fire and TV movies like The Princess and the Marine.

Sony, the first studio set

to release the film got skittish because of the supposedly inflammatory word

in the title. The film was snapped up by Warner Independent Pictures, which

is now releasing it to theaters.

Brooks and Sheth sat down

with us at Drake Hotel in Manhattan

to discuss the movie.

What drove you to make this film?

Albert Brooks: (For) the very reason that I'm able to sit here and have this

discussion with you. After September 11th, I sat

in my house for a year and was scared. All that was happening was in the

first year was that the next one was coming tomorrow. Maybe this weekend.

Maybe on Monday. You saw what happened. I had this little movie that I

was in

–

My First Mister

– that opened in the theater in Rockefeller Center

the day after the Anthrax scare. Oh, that's going to be great. That's what

you want to get a good house. Tell them that there's anthrax in the

theater. That entire year was everybody was panicked. The second year the

attacks were going to come on the holidays. Be careful on July

4th!

I wouldn't go to Time Square on New Year's Eve. I would be careful.

The third year – it's going to come… we’re not sure it's going to come. But

what they kept telling us is that this is never going to go away. Right?

That's what they say to us. Don't get used to this being like other wars.

Other wars have conclusions. This will be around for as long as you will.

One

day I thought; this is insane. So what is our life like? Are we going to

hide until we're killed? You want to get back to a normalcy even if there

is some impending doom. And normalcy is, in my mind, to be able to deal

with it in a motion picture comedy. That's what normalcy is. There have

been no comedies. Certainly not from America. It's interesting if you look

at all the pictures that have risen to the top at the end of 2005 virtually

all of them are set in the past. It’s like that’s how people are (dealing

with things.) Every movie from

Munich

to Brokeback Mountain and Good Night and Good Luck and

Memoirs of a Geisha and Squid and the Whale – these are all

movies from the '70's, '60's and '80's. One way to deal with it is to not

even talk about a world after 2001. Then the comedies that have been made

that (do) deal in the supposed present are generally these teenage sex

comedies anyway that never talk about the world. They talk about getting

laid. So they’re not going to deal with it. So what do you do? I just

thought I just want to find a way to just get in this door. Just to be able

to stand up and say, I’m acknowledging the new world here. Maybe we can get

a few laughs for 98 minutes and then we'll go on. By the way, if ten years

from now, which according to them we're still going to be in this, if there

are a hundred comedies it'll be a better place.

One

day I thought; this is insane. So what is our life like? Are we going to

hide until we're killed? You want to get back to a normalcy even if there

is some impending doom. And normalcy is, in my mind, to be able to deal

with it in a motion picture comedy. That's what normalcy is. There have

been no comedies. Certainly not from America. It's interesting if you look

at all the pictures that have risen to the top at the end of 2005 virtually

all of them are set in the past. It’s like that’s how people are (dealing

with things.) Every movie from

Munich

to Brokeback Mountain and Good Night and Good Luck and

Memoirs of a Geisha and Squid and the Whale – these are all

movies from the '70's, '60's and '80's. One way to deal with it is to not

even talk about a world after 2001. Then the comedies that have been made

that (do) deal in the supposed present are generally these teenage sex

comedies anyway that never talk about the world. They talk about getting

laid. So they’re not going to deal with it. So what do you do? I just

thought I just want to find a way to just get in this door. Just to be able

to stand up and say, I’m acknowledging the new world here. Maybe we can get

a few laughs for 98 minutes and then we'll go on. By the way, if ten years

from now, which according to them we're still going to be in this, if there

are a hundred comedies it'll be a better place.

Sheetal Sheth: I’d heard that the movie was being done and the people involved in

getting the movie together had told him about different actors. And we just

met. It was before the actual physical casting. It was more him kind of

picking my brain about India

and about the culture and about women there. I was like, (sighs and

speaks low) uh-oh, don’t do it about India.

I was all nervous and protective. Then I met him and honestly was so struck

about how specific he was about staying authentic and real. He asked me so

many questions that were so specific. It was so nice, and I was, how do I

be a part of this? Because he’s going to do it with the respect and dignity

that it needs to be done with. Then I was like, okay… whew. (laughs)

Can you talk about what happened with the distribution of this film?

When did you know that Sony was getting cold feet? How did you end up at

Warner Independent Pictures?

Albert Brooks: They wasted five months of our lives, actually. The film was made and

financed by (producer) Steve Bing. He had a deal with Sony. They knew

about the movie, obviously, and they were excited about it. They picked

Tri-Star as the division they thought could best handle this. Then after the

movie was finished I went over there and I had one scene – that Fred

Thompson scene edited – and I showed them that and I told them the rest of

the story and the title. Everyone felt excited after that meeting. I

didn't feel as excited as the others because when I told them the title then

one of the big shots in the meeting sort of made a joke that was weird to

me, like, “Oh, good title. I guess we’re going to have to put in extra phone

lines in to take these calls, huh?” When studios say things like that

there's never anything good about it. If a studio sees a rough cut and

says, “Yeah, that scene was a little long,” that scene is never going to get

into the movie. That’s the way that they let you know something.

So I said in the parking

lot to Steve, I'm worried about that comment. “Don't worry. This is great.”

Okay. So they proceeded and they made posters. They made a trailer. They

had booked us in, you know, they said that we were going to go to the

Toronto film festival and I saw the big release date which was October

seventh. And then, about eight days after that Newsweek story came

out about the Koran being abused in Guantanamo Bay,

I got a call on Monday morning from Steve. He said, “Bad news. So they

don't want to do the title.” Okay. Didn't I say this five months ago? “No.

No. You were right.” You know, one of those things that's supposed to make

you feel better. Gee, I was right. Now my life is over.

So what do they want to

do? “Everything will move along smoothly and they'll call it Looking for

Comedy, if that's okay with you.” No. That's not okay with me.

There's nothing there to that. We can't do it. So I had a conversation

with the head of the movie company and he told me that he just felt that

times had changed and I said, what do you mean? Times changed after 9/11.

They’re not going to change any different. Abu Ghraib was worse than this

and that was a year ago. It's always changing and that's why we're making

the movie. He just said that he was concerned about it. Then quite frankly

I wound up seeing one of the trailers that they made, because I said to him

on the phone, Lets say that I change the title are you going to tell the

audience what the movie is about or are you going to hide it? “No. No.

That's not a problem.” I saw one of these trailers that they made. It was

like Bill and Ted Go to India.

There

was no idea about what the movie is about. A comedian is on his way to

be funny. On his way where? Where are we going?

There

was no idea about what the movie is about. A comedian is on his way to

be funny. On his way where? Where are we going?

Sheetal

Sheth: I knew

what the title is. What’s the big deal? Honestly, I remember I went in to

do some work and Albert is in the middle of all that nonsense. I was like I

don’t get it. I still don’t get it. I don’t think like that, so I guess I

can’t understand it. Even when people explain it to me – I didn’t realize

that we were so far gone to not be able to say Muslim anymore – let alone in

the title of a movie. The thing that is funny to me is that Albert actually

specifically said because there is all that kind of negatory influence

around that word – what can I do to lighten that? What’s the least

offensive, most placid word I could put next to it? That’s comedy. You put

those two words together and hopefully that allows you to kind of lend

yourself to the idea. I just don’t understand what could possibly be

controversial. I think if you see the movie, if anything, it puts everybody

in such a nice light and it’s so intelligent and with some heart on that

side of the world. If anything, it makes fun of Americans, I think.

(laughs)

Albert Brooks: My feeling is, and I don't have any proof of this, but as much as I

understand how very big companies work there are many, many people in a

company that big that aren't really involved in the day-to-day movie

business. The Sony Corporation is in a tremendous amount of businesses and

the movies that they make to some people are meaningless, until one

afternoon when they have nothing to do and they're like, “Let’s see what's

coming up. What is this? Sarah, what's that word?” “Muslim.” “You

sure? Get Charlie on the phone.” So I just think that someone said, “What?

Are you crazy? Get rid of that.” Especially, you know, I'm not someone who

guarantees… (an audience.) I'm not Peter Jackson. They're not going to

have a long, “Well, are we going to have to take some flack, but will we

make half a billion dollars? We'll take the half billion dollars.” I just

think that I couldn't win that argument.

I was upset because

October was now gone. Toronto was gone, but on the positive side I never

would've gone to Dubai

(the film premiered at the

Dubai Film

Festival)

because that would've been too late for that. So that turned out to be like

the coolest thing that ever happened. It's one of those experiences where

you're certain where one thing is going to happen, but something else

happens entirely. So that I sort of think that I'll remember that long after

anything else about this whole movie because it was so wild and unusual.

But you had to know that there was going to be trouble from the start,

right?

Albert Brooks: Yeah. I did know and we could've had (it out at) that February

meeting. What normally happens in the studio is that you go back to your

house and there's a call that says, “Look, they love you. This isn't going

to work out.” No one had the guts to say that then. Then that leaves us a

whole summer to go to Warner Independent and let Warner Independent have

some preparation, instead of in July. Now you’re juggling balls. When do I

come out? I’m coming out January 20th because literally that was the only

day. They're a small studio. They had Good Night and Good Luck.

They had

Paradise (Now).

They don't have a lot of employees. It's not like landing patterns at JFK.

You can't get in. You have to go back to Ohio and start.

So what does make Muslim people laugh?

Albert Brooks: I'll tell you what's funny. As the crew sort of warmed up to me; the

Hindus, the butt of their jokes are the Sikhs. They’ve got Sikh jokes. I

mean, there was one joke that I didn't understand that wasn't like, “How

many Sikhs?” But it was like, “Two Sikhs played a chess game, yes? They

simply did not play.” (laughs) I mean, it was like – what? Okay.

I get it. I understand. Then we had a Sikh driver who was telling me the

Muslim jokes. “Did you hear about the Muslim?” I get it now. I saw the

hierarchy. So it seems to me that everywhere on the planet somebody is

talking about someone else. As I say in the movie, Polish jokes work

everywhere.

Sheetal Sheth:

Like I said, at first I felt very protective and then I spoke to Albert. It

was just so beautiful, and so simply creative and smart. Always a movie I

feel like with great ideas. So I just… I was like, I don’t know, what does

make everybody laugh? (she laughs) I don’t even know what makes

Americans laugh.

Albert

Brooks: The

purpose of the movie was always… this was similar to other movies that I've

made, which were Real Life and Lost in America. One of the

themes I've always liked was the ability to take on these highfalutin’

dramatic projects and I have no clue how to do it. At one point and I'm not

saying that this couldn't even be done as another vehicle on television – if

you were going to… this could be an interesting twelve-part HBO show where

you really do go to different countries and then it becomes a pure

documentary. But the idea of my character having the inability to find this

out and the truth is that it's not very easy to find out anywhere. I've

been doing comedy in this country my whole life and I can't tell you much

about what makes people laugh here. So this idea about finding out what

makes people laugh is pretty hard to do even if you were going to do it

seriously. But it was never the plot of the movie.

Albert

Brooks: The

purpose of the movie was always… this was similar to other movies that I've

made, which were Real Life and Lost in America. One of the

themes I've always liked was the ability to take on these highfalutin’

dramatic projects and I have no clue how to do it. At one point and I'm not

saying that this couldn't even be done as another vehicle on television – if

you were going to… this could be an interesting twelve-part HBO show where

you really do go to different countries and then it becomes a pure

documentary. But the idea of my character having the inability to find this

out and the truth is that it's not very easy to find out anywhere. I've

been doing comedy in this country my whole life and I can't tell you much

about what makes people laugh here. So this idea about finding out what

makes people laugh is pretty hard to do even if you were going to do it

seriously. But it was never the plot of the movie.

Sheetal Sheth:

Here’s the thing, right? I think it’s funny. It’s not a documentary. It’s

a comedy. It’s really about – we’re all people. We all laugh at different

things. I couldn’t tell you what you guys are going to laugh at as much as

I could tell anybody from India and Pakistan or anybody in the world. We

all laugh at different things. We’re moved by different things. My family

laughs at things that I think are ridiculous. (laughs)

What about jokes about the Palestinians?

Albert Brooks:

Well, I heard a Palestinian joke yesterday, somebody told me... I'm trying

to think if remember. The big sacrilegious thing is for a person like me to

tell a joke badly. These two Jewish men travel the subway everyday for

years and years and read the Jewish press every morning. Then one morning

one of them is reading an Arabic newspaper and the other one says, “What's a

matter with you? What's happened to you? Why are you reading that paper?

Have you lost your mind?” He said, “No. To tell you the truth all I read

in the Jewish paper is that Israel

has been blown up and that the Jews aren't allowed to enter and that life is

terrible. In this paper it says we own all the banks. We own the media.

Life is much better in this paper.”

Woody Allen said earlier this year that he’d do standup again, but it’s

easier for him to make movies. What about you? Would you consider going

back to do standup?

Albert Brooks:

Well, let me address why it's easier for him, and I admire that he can make

so many movies. But Woody Allen is the only person, the only person who

somehow – and I think that he started that way and he's still able to do it

– he doesn't do the publicity. He doesn't do any of this stuff that all of

us have to do to sell. So he finishes, goes back to his house and starts to

write again. That's a great luxury just to never get into the business part

of the business of making movies. I've had to raise the money. I've also

had to do as much as I'm able to do this part. I enjoy this part more than

he does. Especially with this movie, the discussions are interesting. It

feels more political just to talk about the world. But that's all he ever

did. He never previews. He never does anything. He just makes one movie

after another and that's an amazing luxury. I've thought about doing

standup. I don't know how serious I am about it. I see some of the new

places in Las Vegas.

Those rooms are so beautiful and they pay well, God knows. I don't know.

It would have to be a different mindset.

Did

you try to recreate your act in the film?

Did

you try to recreate your act in the film?

Albert Brooks: Oh, God no. My act is better than that. By the way, that improv bit

is a really cool comic thing. But I wrote that for the movie. I never

really did that bit onstage. Danny and Dave I used to do all the time. The

jokes, you know as I say to them, “I’m going to try stuff at the bottom of

the barrel and intellectual stuff.” So I have more bottom of the barrel. I

don’t know what I would do if I were really, really just going to do standup

in India. I don't

know what I would do. Now I think that I've scared myself out of ever doing

it.

When you did that, where you just doing standup as they sat there and

watched you silently?

Albert Brooks:

Remember I'm the director and we have to get those people. That was filmed

over two days because you have to shoot from sixty different angles and so

in the beginning of the first day – first of all, I'm talking to them as the

director and welcoming them. Their inclination because they want to and

they have a lot of energy is that they were laughing at everything. Then

you have to tell them not to laugh and so then you go through a period where

once you tell people not to laugh two people do, and everyone laughs at

them. But fortunately you put in the heat and you put in five hours without

a break and no one is laughing anymore. As a matter of fact you get a few

people going, (yells) “When do we get to eat?!” I'm like, that you

can't say either. Don't yell at me. Just be quiet.

How was it to watch Albert do stand-up? We’re probably not going to ever

get to see that…

Sheetal Sheth:

From one of my meetings with him, he literally acted out the movie.

Because, he doesn’t let anyone read the script and I begged him after the

fact. I begged him to please let me read it before we do it. So he acted

out the whole movie for me. It was like a two-hour seeing Albert do his

thing. It was just such a high. (laughs) I was there just

listening and watching and kind of taking it all in. Working with him, he

obviously has a script and he really is very strict about staying to it, but

then he likes to work to the moment. So he’s just constantly improvising

and just seeing him go... We were just all – me and the two Johns

(John Carroll Lynch and Jon Tenney, who play the two government agents

assigned to Brooks) were just in awe of him. We were like, wow,

we get to see Albert Brooks do this every day.

So

he didn’t show you the script first?

Sheetal Sheth:

No. Even when I was auditioning, I didn’t realize until after that the

sides that we were using weren’t from the script. He just kind of wrote

something somewhat related. Then, on my very last meeting with him, before

he asked about the movie, I signed a bunch of confidentiality agreements.

Then he did that and then kind of, for the first time, cold read scenes

together. Then he told me I got the part. When we were talking for the

month before we went to India,

I said (begging) “Albert, can’t I please read the script?”

(laughs) He’s like, “No, don’t worry. It’s fine. You’ll be fine.”

Then he finally let a few of us, we went to his office alone when he was

there and we read it and we gave it back to him and that was the last time I

ever saw the script.

Did

the Indian authorities know what the premise of the movie was about?

Did

the Indian authorities know what the premise of the movie was about?

Albert Brooks: Oh, everything. They knew everything.

Did you send them a script?

Albert Brooks:

I was able to… because at the time I was still writing. When I went there

initially I told every beat of the movie, and then I sent a forty five page

description of every scene. And they had minders that sometimes they didn't

come to the set, but they had that right to listen. I wasn't trying… you

know, in my heart I wasn't pulling a fast one. So I wasn't worried. I was

really worried in my first meeting with the Minister of Culture when I went

there, I'm describing the thing, and then of course my character comes

because the government doesn't send me or doesn't even care, and then you

guys don't even know what I'm doing here. Pakistan

certainly doesn't, and it sort of starts a (mumbles) you know, war

between the two… (in Pakistani accent) “I'm sorry. What does it

do?” Oh, you know, it starts a war between the two countries. They didn't

mind that because I started to watch the Bollywood movies – they've been

dealing with Pakistan… this relationship is a lot greater than my… I'm not

the first one who came up with what do you guys do with Pakistan?

They deal with that.

What

they do mind, they had other issues. There were religious issues. As I

said to Letterman which was true, the guy told me that they wouldn't let

Raiders of the Lost Ark shoot there because there was a scene where they

ate monkey brains. (It was actually the second

Indiana Jones movie.) Actually what I told the Minister very respectfully, you know, you

really in the future should take our money and let us do it because now with

CGI they'll make any place look like India and they'll do all the things

that you don't want anyway, and so at least get our money.

At the end, Albert leaves, there is no war and everything is fine

again. Why?

Albert Brooks: Well, it wasn’t fine again. By the way, the opposite of that, they

dropped looking for comedy and they put their money in a bomber that doesn't

have to leave the hangar. So it's not fine again. But it's a very good

question and one of the reasons for that first sentence is actually a

promise that I had made to the Indian Government. I said I will let the

India/Pakistani conflict at least be… it was my fault… and not leave the

movie feeling that you guys were at war.

What about conservative former Senator Fred Dalton

Thompson (who plays a fictionalized version of himself)? What did he think

about it?

Albert Brooks: We had a screen in Washington on Sunday at

the Center for American Progress and he was there and John Kerry came, and

he saw the movie for the first time and he was pleased. Fred Thompson –

that was something that he was hesitant to do because he'd never played his

own name and he worried about it. He was a fan. When I cast Rip Torn in

Defending Your Life, he was the other guy. They both came down to the

wire. I had known Fred and he liked me, but you know his own name, he was

worried. But he said, “Well, I'll trust you.” He actually said, “You're

not going to pull a Michael Moore here are you?” I said, no, Fred. That's

not what I'm doing. This is the movie. Then coincidentally after the movie

was already finished I was sort of pleased that Fred was the guy appointed

to lead John Roberts through the Senate because it raised his political “Q”

(quotient). He was all of a sudden back on Fox News talking about John

Roberts. It was good.

Being familiar with both worlds – The US and India – is

there really that much difference?

Being familiar with both worlds – The US and India – is

there really that much difference?

Sheetal Sheth:

I think I’m as American as anybody else. I think American especially means

a mix of cultures. To me all-American isn’t blonde and blue-eyed. I think

if someone ethnically is kind of questionable, that’s America to me,

actually. India is my home. It’s where my family is. I love it. I love

it as much as I love being here. I’ve spent so much time there. There’s

nothing like the people there. Really, the heart is unbelievable.

How do you think American relations with the Middle East

can be helped?

Albert Brooks: I don't know what the solution is, but what we really need to do is

that we don't have any public relations this country. That was the whole

idea anyway. I call it the Schmooze Corps. We have fifty thousand people

on the ground just to look people in the eye and take them to jail. There's

no interpersonal contact with America and the rest of

the world anymore. The current leadership doesn't choose to do that.

Remember when Kennedy went to Berlin and said one sentence in German and

they loved us for twenty years. There's just no attempt at this and it

blows my mind. It's really upsetting to me.

Indians who aren’t Americanized like you, how do you think they’ll react?

Sheetal Sheth:

I think they’re going to welcome it, I really do. To see people that they

recognize, that look like them, that talk like them. That are saying things

and people are reacting. And seeing how ignorant we all can be when going

to certain places. I think they’re going to laugh and going to love it.

Since India is a predominately Hindu nation, did you try to go to other Muslim

countries first?

Albert Brooks: No. India and

Pakistan was always part of the plot. I had a number of issues to deal

with. One, you need some jeopardy when they give you this assignment and

Americans don't readily go to Pakistan and Pakistan is a Muslim country.

Obviously, as it's explained in the movie in India the Hindus are the

majority of the population, but what makes India interesting is that their

minority population makes it the second largest Muslim population in the

world. It's just so many people.

Sheetal Sheth:

I guess everyone defines a country in different ways. I don’t really know

India as specifically… I’m not sure what that means in terms of when you say

“a Muslim country” or “a Hindu country” or “an American” or “a Catholic.” I

don’t really get that, because I feel we’re a mix of so many different

things. I can understand why people would say that, I mean, considering the

nature of our government and the world it seems to lend itself that way.

(laughs) But obviously, what we stand for – you know, we separate

church and state. And so does India. We’re supposed to. (laughs again)

We’re supposed to where some countries don’t… Albert has already said that

not many Saudi Arabian countries would have allowed them to actually film

there. He tried to call some people.

Albert

Brooks: But even if it is my initial desire, I cannot go to any of the

countries in the Middle East that would provide jeopardy for the movie. There is no

Saudi Arabian Film Commission that's welcoming people. When the President

of Iran says that they want to wipe Israel off the map on

Wednesday, Thursday he's not saying, “However, let the Jew filmmaker come in

and we'll give him free access to the sites.” I can’t get into Syria.

So where I would be able to film where like Syriana filmed is not

interesting for this movie, which is like Morocco. You go to Morocco and

that's too touristy. Egypt is full of people from Florida looking at

pyramids. So the countries that everyone is ooh in the Middle East

aren't inviting a person like myself. I don't think that there are any

American films that are readily getting in there. There are news crews

obviously that can shoot in Iraq, but getting a movie made you need the kind

of cooperation that our governments can’t even get when they talk to each

other. I don’t know how unions are then going to speak to each other.

Albert

Brooks: But even if it is my initial desire, I cannot go to any of the

countries in the Middle East that would provide jeopardy for the movie. There is no

Saudi Arabian Film Commission that's welcoming people. When the President

of Iran says that they want to wipe Israel off the map on

Wednesday, Thursday he's not saying, “However, let the Jew filmmaker come in

and we'll give him free access to the sites.” I can’t get into Syria.

So where I would be able to film where like Syriana filmed is not

interesting for this movie, which is like Morocco. You go to Morocco and

that's too touristy. Egypt is full of people from Florida looking at

pyramids. So the countries that everyone is ooh in the Middle East

aren't inviting a person like myself. I don't think that there are any

American films that are readily getting in there. There are news crews

obviously that can shoot in Iraq, but getting a movie made you need the kind

of cooperation that our governments can’t even get when they talk to each

other. I don’t know how unions are then going to speak to each other.

Sheetal Sheth:

There are three things. It’s that, number two there’s a relationship

between India

and Pakistan, which is the point of the movie. Kind of creating this… war.

You need that already present. And there’s a relationship with America with

them. And number three, that’s kind of the point! That’s the point

of the movie, in the sense that the government and the people are so

ignorant to think that’s where they would send him. (laughs) You

know? That’s the joke!

Were you familiar with Albert’s movies before? Did you find them funny?

Sheetal Sheth:

Yes. I was quite a fan. Then, before I shot I was, I should probably

review. I wanted to remember his style. So I ended up renting as many

movies I could find of his again. And I made my friends watch them with

me. (laughs)

Albert Brooks: I was hairier then.

What was your favorite movie of his?

Sheetal Sheth:

I think Defending Your Life.

Not The

In-Laws? (which is ridiculed by director Penny Marshall early in

Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World.)

Sheetal Sheth:

(laughs) That’s not like his. I’m thinking of his that he wrote.

This is a really smart film. Do you think audiences will get it?

Albert Brooks: I'll tell you something. If I really asked myself those questions I'd

never be around. I wouldn't be talking to you today. I would've retired

when I was thirty. My whole life, you have to understand, is dealing with

people. The Dean Martin Golddigger Show (in 1969), one of the guys

who gave me my start, Greg Garrison (the director of the show) allowed me to

do the kind of comedy (that I did). But he felt that it was necessary to

give me a lecture like his child before it all started. He took me in his

office and he said, “I just want to tell you something. You're going to

have a very tough career because you’re here and the audience is here.

If I were you I would adjust for that.” He looked at me to listen for my

answer. And my answer was I don't know what you're talking about. He said,

“I just wanted to check. Go do what you do.” I think if I said you're

right, let me go and rework it – that’s what he was trying to see. One of

the most famous sayings in the history of show business is you'll never go

broke by underestimating… That’s all people do, underestimate the audience.

I can't think like that.

Features

Return to the features page