Copyright ©2008 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Posted:

February 14, 2008.

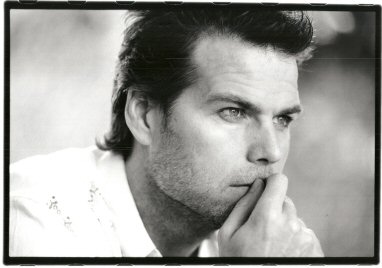

Even

the words "driven" or "obsessive" would be considered laughable

understatements when describing Bo Eason. His semi-autobiographical

off-Broadway play, Runt of the Litter, is about a little engine that

could;

it's pleasing critics and audiences alike and making its way from

New York to Hollywood.

Also

doing the pleasing is Eason himself, who stars in this one-man show about

his struggles in and out of the stadium. Growing up in a football-obsessed

family in small-town Texas, the sport is in his blood, both when spilling it

on the field or spilling it and his guts onto paper.

The

former collegiate All-American and safety for the Houston Oilers (1984-89)

and now a sought-after actor and writer had nothing handed to him in life

except a football.

And

even that, he busted his ass for.

In

fact, the word "no" was usually his green light.

"People told me my whole life that I couldn't," he recalls in the empty

theater at 37 Arts in Manhattan, a few hours before showtime. "And it would

set me back, and I would get so mad that I would cry. And I would go and

train harder. I would do whatever it took to get that anger and that passion

out of me, because it was driving me crazy that people would say, 'oh, you

can't do it. You're too small. You can't [play football at] our school.

You're too this or that. I always had that coming at me but I never

stopped."

Typical

safety. Yet there was nothing safe about the likelihood of his dream coming

true.

Typical

safety. Yet there was nothing safe about the likelihood of his dream coming

true.

His

determination to be a part of a sport, despite his size or ability and to

eventually excel in a big way was just short of Glenn Close in Fatal

Attraction.

"I

got cut from my first baseball tryout when I was thirteen," he says, "and I

grew up in a tiny little town. Every little boy basically had to play. I was

so embarrassed and the coach, who I still know to this day, always says to

me, 'I'm the only coach ever to cut you.'

"But

what I did, when I got cut when I was thirteen, is that I never went away. I

did not go away. I'm showing up to practice and everybody is like, 'why are

you here? You're not on the team.' And I say, 'no, I'm just going to

practice.'

"They would say, 'what do you mean, practice? You can't practice. You're not

on the team!" And I said, 'If I'm not good enough to be on the team than I

need the most practice.'

"That's how my brain worked. I need practice more than anybody. You guys

don't need practice. You are already on the team."

If

you've ever seen a sports movie, you know what happens next.

"Eventually, the coach let me play," Eason says, "because I showed up more

than the other guys who were on the team. Eventually, he gave me a uniform

and let me play."

This

would make for a nice little anecdote, but, amazingly, the story doesn't end

there. Eason's focused way of doing things stayed with him, even through

college, as he actually stuck with his twenty-year plan to forge a career in

football.

"In

college [football tryouts]," he says. "I was sent home. But I didn't go

home. I just stayed and stayed and stayed. And kept going to practice and

going to practice.

"The

coaches would walk around saying, 'who is this kid? Didn't we send him home

like two weeks ago? We don't want him around. Get him out of here.' But I

just kept on showing up and showing up, in goofy uniforms that didn't match

the team's. Eventually, they said that if that kid is that committed, let's

keep him around."

Good

thing, too. Eason eventually made All-American, and the pros.

Good

thing, too. Eason eventually made All-American, and the pros.

Psychoanalysts

would have a field day dissecting this patient, but most of what made Eason

run was obvious. He had an older brother, Tony, who was a football hero, and

would eventually become a quarterback for the New England Patriots. He

looked up to him, while simultaneously trying to dig himself out from his

shadow. As the subtitle to the show reads: He Was Second To One.

The

play, though mostly grounded in autobiographical fact, stirs in an

intriguing "what if:" Eason himself having to go head-to-head with his big

brother on the field. It makes for great drama, but at one point, the

brother-vs.-brother conflict had almost become non-fiction.

"As

fate would have it," Eason says, "right when we were going to play that

game, the players went on strike. That game didn't happen. So we never

played against each other. That always kind of gnawed at me. I was relieved

that I didn't have to make the decisions that I have to make in the story.

It's really the reason I wrote the play. I think it was ten or twelve years

after that. I just said, 'wow, what if I had to get dressed to achieve my

twenty-year plan for the last time, and the obstacle being my brother

standing in the way of all the dreams that I had in my whole life. I would

be playing against the person that I love the most and the person most

responsible for me getting there."

Eason's twenty-year plan, starting at age nine, was to become a professional

football player. Unlike most kids who conceive and stick to a plan like this

for about fifteen minutes, Eason saw it through to the end.

"I

didn't come up with the whole plan at nine, but it built," he says. "I kept

growing it. I didn't know the position of safety when I was nine, but when I

was thirteen, I did. So I said, 'safety, that's what I gotta play.'

"My

brother and I played catch for two and a half hours every day. If you play

like that, that was about a thousand balls [per day]. Later in my life,

because I was on this roll of catching a thousand a day, I would just bounce

them off the wall because I would run out of friends to throw them to me.

You can go much faster that way."

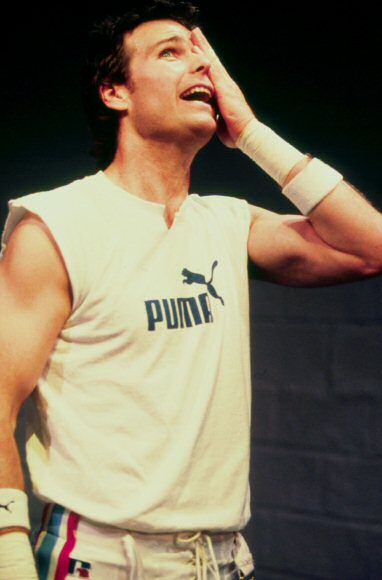

Life

came at him as fast as the footballs. After his stint in the pros, he

pursued his other long-time interest in becoming an actor.

He appeared in Miami

Rhapsody with Sarah Jessica Parker and will appear in Pride and Glory

with Edward Norton and Colin Farrell. He also made numerous TV appearances,

including ER.

"I

always had one eye on our theater department," he says about his first

introduction to drama in high school. "Our theater department was really

small too. And they'd put on Our Town and Skin of Our Teeth

and all these plays. And I would always go and I would always watch but I

would never tell anybody. I loved stage acting. It just looked like a lot of

fun. It looked like an athletic event to me. That's how I saw it.

"Once

I attended college, I majored in political science, but I minored in drama.

So I would always sneak over after practice and go to acting classes. But I

never told anybody. Those two worlds just never crossed over. I thought

everyone would tease me.

"Once

I attended college, I majored in political science, but I minored in drama.

So I would always sneak over after practice and go to acting classes. But I

never told anybody. Those two worlds just never crossed over. I thought

everyone would tease me.

"I

got drafted in the pros, and in the off season I would study acting. And as

soon as I finished completely with the pros, I moved straight to New York

and I started studying like a madman. Five, six, seven, eight years in a

theater, just putting up scene after scene. Trying to learn it. Trying to

get good at it."

Sound familiar? That incredible discipline followed him when he decided to

write Runt of the Litter, which started out as an exercise in an

acting class, but has now been finely honed since 2002 as a one-man show.

He

says, "I would go to a Borders bookstore in Hollywood near where I lived,

and write for three hours a day, every day, for two years. Writing hasn't

been fun for me. It's lonely."

The

loneliness paid off, though, as the play has aroused the interest of many

hot young actors such as Leonardo DiCaprio, Toby Maguire, Nicholas Cage,

James Franco, and Ryan Phillippe.

In

fact, DiCaprio has commissioned Eason to write a screenplay on the 1924

Olympic Rugby team, which will be produced by DiCaprio's production company.

He is also working on a remake of the seventies TV-movie football classic,

Something for Joey.

Runt of the Litter

is directed by the well-respected Larry Moss (who has also been on the

teaching staff of Juilliard and Circle in the Square). Eason's wife is the

producer of the play, and he is a late-life dad of two young children.

The

play itself has been bought by Frank Darabont (writer and director of The

Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile) for an adaption to the

screen (written by Eason).

For

Eason, the play itself is more Ordinary People than Rudy.

"I

had no idea it was dark," he says. "Larry Moss saw me do it in his class. To

me, it was like this love letter to my family. It was motivational. It was

inspiring. It was my life. It was what I knew. But Larry just shook his head

and said that is one of the most tragic stories he's ever heard. I didn't

see it like that. I did realize that my life has some tragedy to it, but

because it was my life, it didn't seem that way. I didn't know it was as

dark as it was. People like it, but they tell me that it's violent and dark.

I just never thought that it would go in that direction."

Although

his own father had never seen a play in his life until he saw his son

perform, and Eason himself has to keep his energy level high for such a

daily psychological and physical demand, Eason says it's all for the

family.

Although

his own father had never seen a play in his life until he saw his son

perform, and Eason himself has to keep his energy level high for such a

daily psychological and physical demand, Eason says it's all for the

family.

"This story is about the real relationship with your mom and your dad, not

the kind you see on TV, but the real ones. Those are touching, man, because

they are so dangerous and scary and painful. Trying to

please them and trying

to get love. Trying to be a success in their eyes. That's what I mean by

dark. It hits you so hard."

Speaking of being hit hard, he now sees without the blinders on.

"I'll be forty-seven next month," he says. "Now, at forty-seven, I look back

at that little nine-year-old as if I were not him, and I think, man, that

little nine-year-old was touched by something."

His

unorthodox method for getting to where he needs to be is considered

admirable and unusual by everybody but him.

"It's the only way I know to bring what I dream about into existence," he

says. "It's the only way I know how."

For

now, with his plate this full, his production continues to build it so that

they will come.

Email

us Let us

know what you

think.

Features

Return to the features page.